Previous – 3. Escape To New York | Contents | Next – 5. Making It Personal

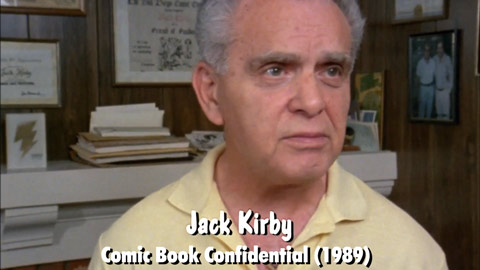

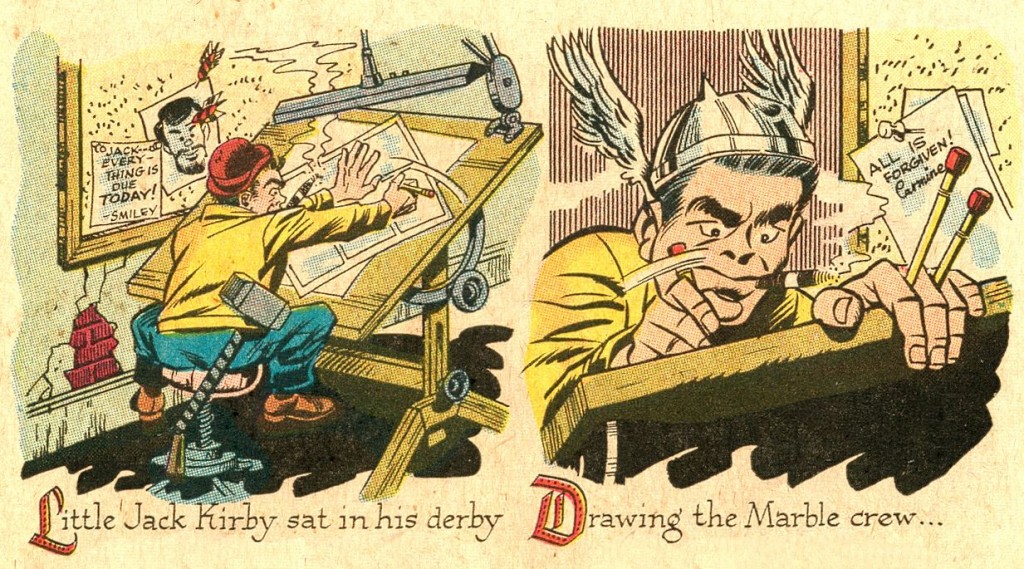

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

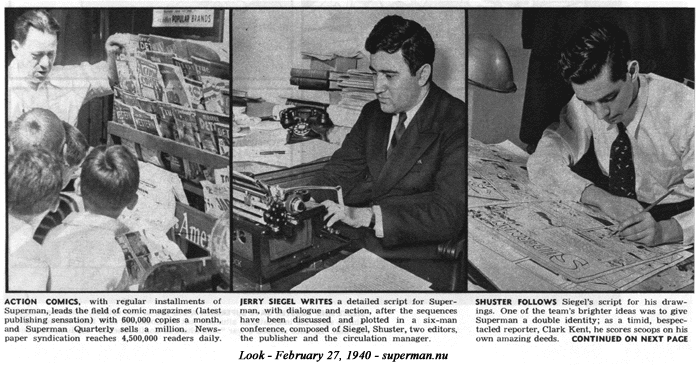

1940, THE YEAR OF LIVING FURIOUSLY

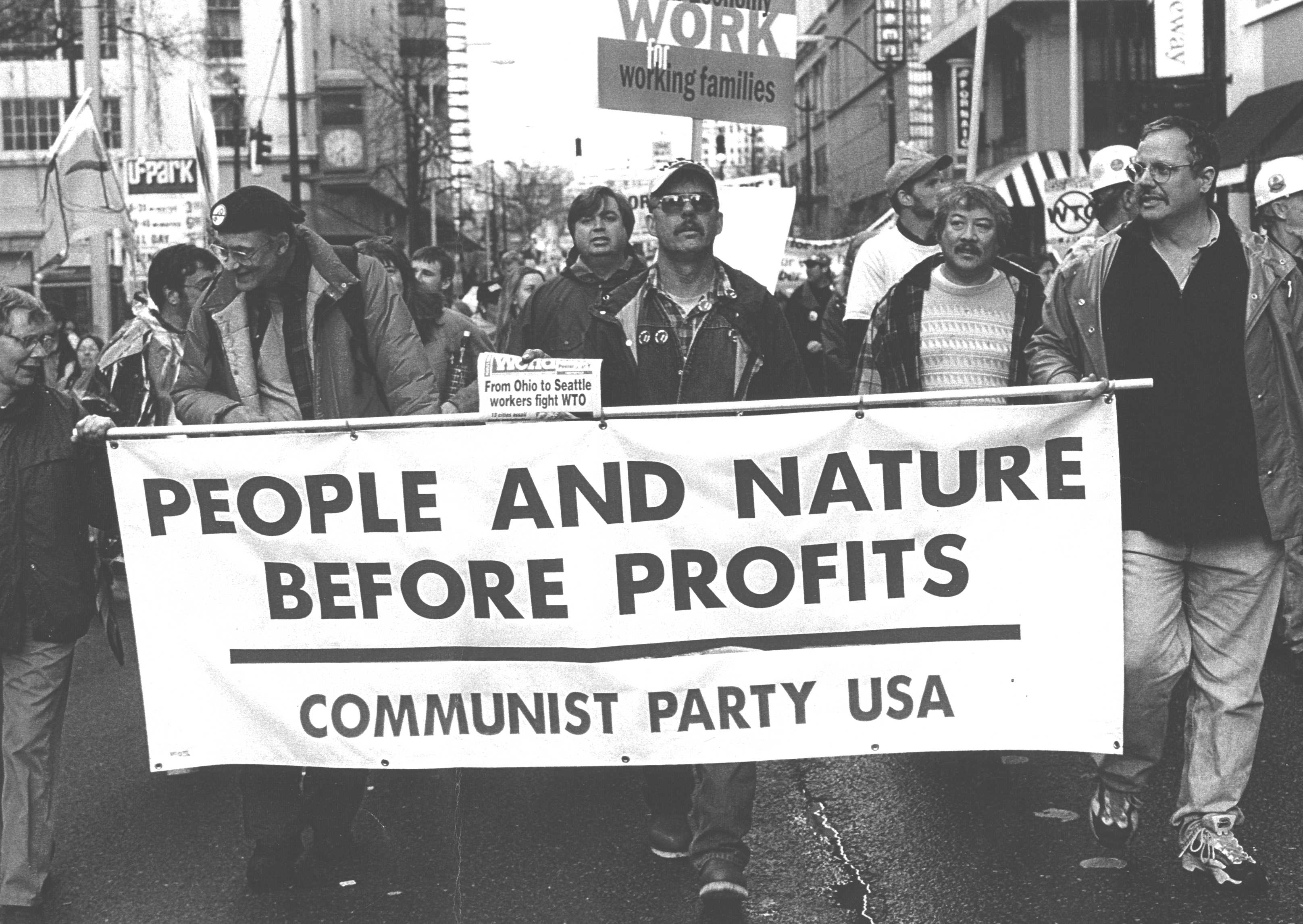

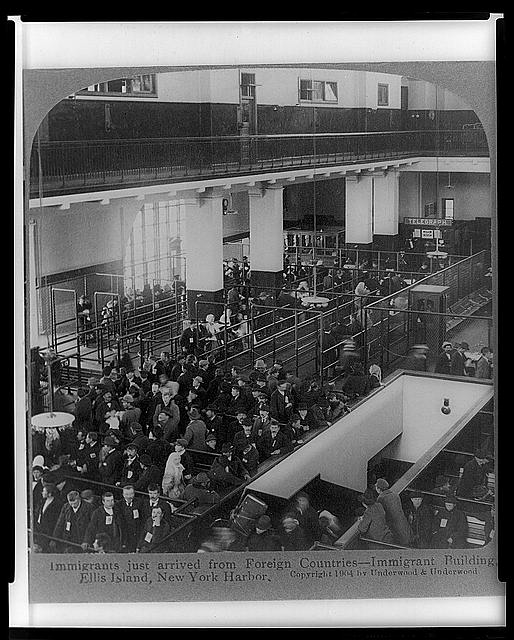

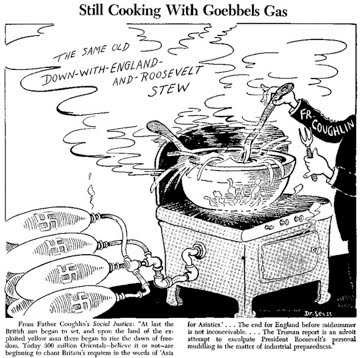

Once again all of Europe was at war. With its daunted Blitzkrieg, Germany had invaded Czechoslovakia and Poland. Holland, Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands were imminent targets. Great Britain, France, Canada, and Australia had declared war on Germany. The U.S. was ostensibly neutral, but to the European immigrants of Jewish descent, Hitler had made it personal.

“Today I will once more be a prophet: if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevizing of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!”

– Adolf Hitler,1939

Kirby knew that war was coming, everyone knew, but he had his own personal battles to wage. For three years Jack had toiled in the minor leagues of the comic art world. He had worked for many companies, and with many people whose talents were nowhere near his level. Yet he sat at a small cubicle at Fox Publications and watched as Will Eisner would bring in pages by lesser artists like Art Peddy or a Bob Powell. A crude rookie like Jim Mooney had a recurring strip in Fox’s titles. Even his old colleague at Lincoln, Larry Antonette was producing a strip for Timely, and Better Publications. Meanwhile he was stuck doing janitorial work on other’s art and fighting for scraps to fill out his time–so many promising starts, only to see them fall by the wayside. His dreams of artistic success were being crushed in a low paying, menial role.

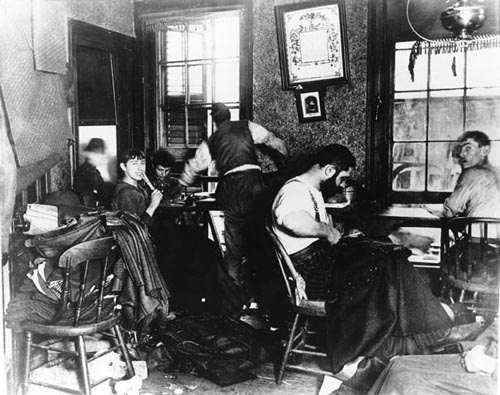

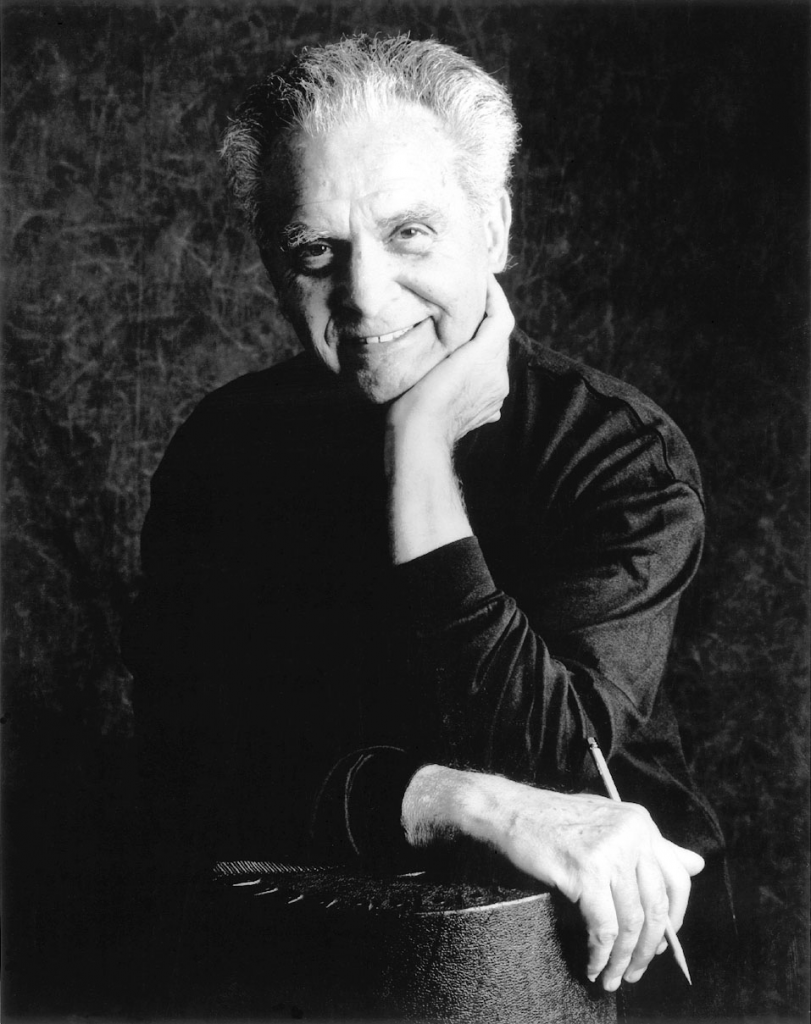

For all of Kirby’s confidence in his artwork, his childhood had left several psychological scars. The taunting because of his height, his failure to finish high school, and his impoverished upbringing had left him with a feeling of inadequacy which hindered him when dealing with publishers and professional people. As Jack would tell it, “I was 5’4”. The publishers would not look at me, and I took it in stride. I knew they wouldn’t take me seriously.” “I’m a competitor, I made up my mind to beat five guys, ten guys because I was a little guy, and you’ll find that little guys are cantankerous, independent, and they want to be themselves. Of course you’ll find that among big guys too, but more so I think among the smaller people because that had to fight to be noticed.” Will Eisner loved to tell of an incident where he was being pressured by some bent-nosed type to accept inferior towel service at the studio. When the voices became louder, Jack Kirby, working away at his table recognized the sound of strong arm bullying, came out of the art studio and with finger securely pressed in the punks chest, physically confronted the large burly punk, letting him know in no uncertain terms that if he bothered Will again he would answer to Kirby personally. The tough never bothered Eisner again. This ferocity that Jack displayed to the hood could never be found when dealing with publishers or other “suits.” Jack understood the petty hoods, they talked the same language, and they were of his neighborhood. Confronting them was second nature. But the swells or the upper crust could never be understood by Kirby; he would swallow his pride and quietly do what he was asked. His defense was to become more invisible, and work even harder. The overriding fear of becoming like his father and not being able to support his family would never leave him. “The ghetto will scar you for life. I was determined to draw better than five other guys. I was determined to draw better than ten other guys. I was determined to put whatever I knew to work to get me out.”

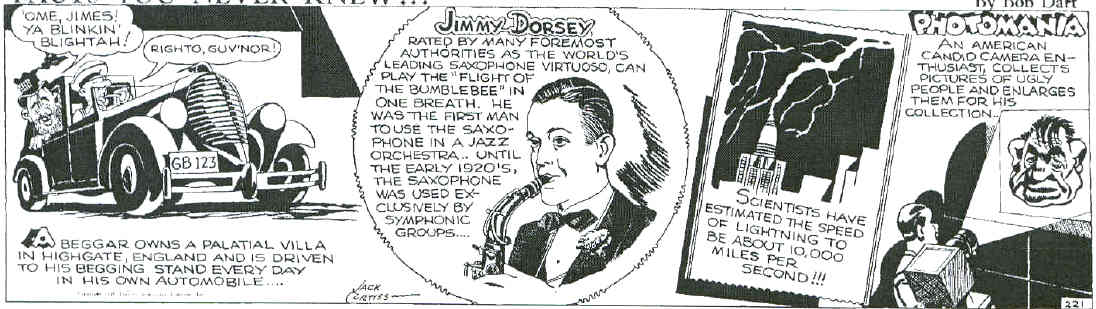

Being Jewish was also a problem. Getting hired at a fancy syndicate was out of reach. Despite denials from Kirby, he knew that his last name stamped him as an outsider. It wasn’t for nothing that his pseudonyms at Lincoln were all Anglicized. Jewish illustrators and writers entered the comic-book field because other areas of commercial illustration were virtually closed to them. “We couldn’t get into newspaper strips or advertising; ad agencies wouldn’t hire a Jew,” explains Al Jaffee. “One of the reasons we Jews drifted into the comic-book business is that most of the comic-book publishers were Jewish. So there was no discrimination there.” But an Anglo pseudonym made it easier so Eli Katz became Gil Kane, or Robert Pavlowski became Bob Powell. Jacob Kurtzberg became Jack Curtis became Lance Kirby became Jack Kirby—a name to be taken seriously. Gil Kane remembered; “location also played an important role. The comic book was born in New York City, and because the industry was so new, it was wide open to the children of immigrants, particularly those on the Lower East Side. “It never really occured to me that there were an inordinate amount of Jews in the business, although in retrospect I can see that,” says Jack Abel. “But then it just seemed like we were all New York guys. Kids growing up in New York saw themselves as comic book artists and gravitated toward that.” But being Jewish did present problems to the publishers whose readers spanned the whole country. Though created by Jews, the characters were lily white Aryan.

“Most of us, at the time, were trying to ‘pass.’ That was the thing to do,” says Eisner. “As a rule, we tended to try to keep our culture out of our work,” agrees Abel. “But you could say the same thing about the Catholics in the business. You never saw an Italian character, for example.” “In those days, you just didn’t go around writing about Jewish heroes,” adds Simon.

Looking up at the tall slender Joe Simon, there was no reason for Jack Kirby to think of Joe as a major league talent scout, yet Jack was duly impressed by Joe’s twin symbols of status–height and a nice suit. “Joe was highly visible, being 6’3’ and being a reporter on the Syracuse Journal. I admired Joe tremendously for that. I admired him for going to college, and I admired Joe for coming from what I thought was a middle class background.” Jack further recalls, “I gravitated to Joe because I had never seen a guy from Syracuse, New York. I would run home and tell my parents that I knew a guy from Syracuse. Yeah…and he wears great suits. You ought to see the suits this guy wears.”

Kirby’s gross exaggeration of Joe Simon’s background and resume says more about Jack’s own inadequacies than of Joe’s superior qualities. The truth is Joe Simon was from Rochester, New York, and his childhood wasn’t much different than Jack’s. Four years Jack’s senior, his father was also a tailor, who specialized in suits, thus Joe’s natty appearance. The family suffered through periods of unemployment-often brought on by his father’s role in union organizing. If the Simon’s life was any better than the Kurtzberg’s than it was only by degrees, Rochester’s slums weren’t New Yorks. Joe’s early influences were the same as Jack’s; “the highlight of the week (was) when my sister and I finally had our turn at the Sunday Funnies with their spectacular color cartoon pages. We devoured each cartoon strip.”

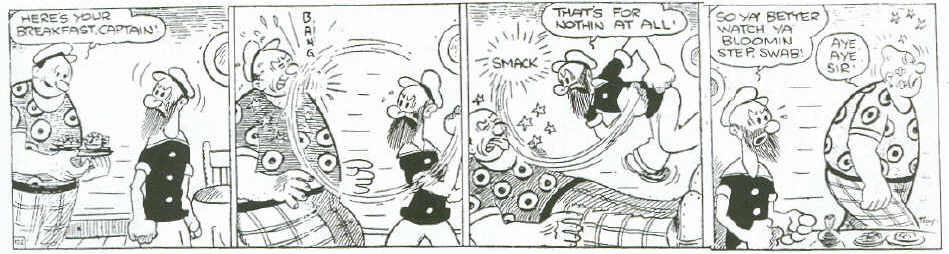

Joltin’ Joe Simon – The Fiery Mask sketchy, boring and wordy abysmal lettering – nobody cared

Joe lived for the movies; he would talk for hours about the inspiration he got from the great directors. Drawing from a young age, he became serious at Benjamin Franklin High School, where as art director he produced spot art for his year book. The art was so good that a couple universities paid ten dollars for publication rights for their yearbooks. In a scene that would repeat throughout his career, Joe had to fight his school to get his money.

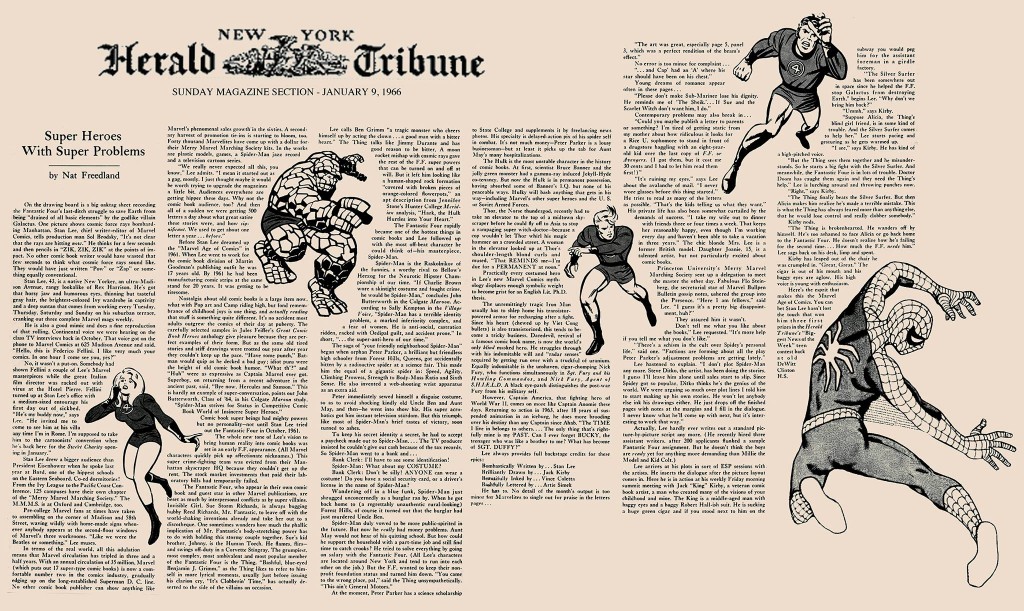

Joe never went to college, when he graduated high school in 1932; he immediately went to work for the Rochester Journal American newspaper in the art department. He began as an assistant, learning the art of retouching photos. He mastered the air brush, and honed the skills of cutting and pasting. He had a knack for laying out well designed photo spreads. After a couple years, he moved on to the Syracuse Herald, where he would become the art director. Among the day-to-day proof up chores, Joe was able to provide original art. He loved doing sports cartoons spotlighting local athletes and upcoming sporting events. He provided spot illustrations for the serialized novels printed every weekend. Unfortunately, the Herald was bought out and in 1936 Joe decided to head to the Big Apple.

Joe’s first job in New York came in the photo retouch department of Paramount Pictures. There he would embellish studio photos of the stars; erasing wrinkles, slenderizing figures, and lifting and enhancing famous bust lines. “I retouched some of the most notable bosoms in pictures” Joe would recall with a wry smile. This was a thankless and joyless career, so Joe continued to look elsewhere.

Early solo Joe Simon – interesting fonts

Bernarr Macfadden had built a fascination for physical fitness into the largest publishing empire of the 20th Century. Macfadden’s’ largest selling magazine was True Story. The main attraction was that these lurid tales were written by “real” people. In fact, most of these stories were written by professional writers using pseudonyms. By 1926, True Stories had a circulation nearing 2 million copies per issue. This success was followed by True Romance, True Ghost Stories and True Detective. Though slicks, these successes would lead to the birth of the pulp industry that expanded on the true confessional genre with even racier, tawdrier and cheaper detective and romance books. Joe managed to pick up work for Macfadden Publications, where he would provide spot illustrations for its line of slick magazines. In his bio Joe explained; “Artist’s were abundant but only a handful made it to the top. These few became rich and famous. Artists such as James Montgomery Flagg, and before him, John Held Jr. were celebrities, but the glamour often vanished abruptly as different styles became popular. One day an artist might be in vogue–the next day a has-been.” Harlan Crandall was a crotchety old guy, but he liked the young man. The art director at Macfadden suggested that Joe try his hand at a different venture in a relatively new industry. Harlan slipped Joe a piece of paper with a name and an address, one that would take Joe to the offices of Funnies Inc.

Funnies Inc. was another early comic art studio, owned and run by Colonel Lloyd Jacquet. Jacquet was an ex-military man, a dead ringer for Douglas McArthur and one of the original editors for Wheeler-Nicholson’s New Comics. Not surprising, Jacquet left Nicholson over a dispute concerning payment. He next turned up at Centaur Publications, a new comic publisher, where he edited some of the books. There he met Bill Everett, an up and coming artist, and decided to open his own shop. Taking Everett with him as art director, plus artists Carl Burgos, and Paul Gustavson, he sought his fortune. After a failed try at a movie premium to be given away at local theaters, he next tried comic books. Funnies soon picked up several accounts; chief among them was Timely Publications, followed quickly by Novelty Press and Famous Funnies. Joe would marvel at his shined shoes and spit and polish military reserve.

First for Funnies Inc. – First Timely for Joe Simon ugly costume bad perspective

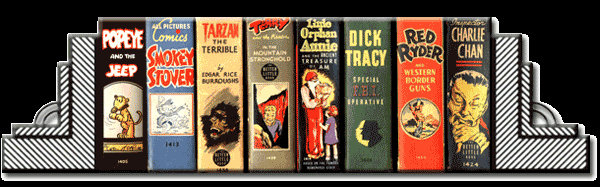

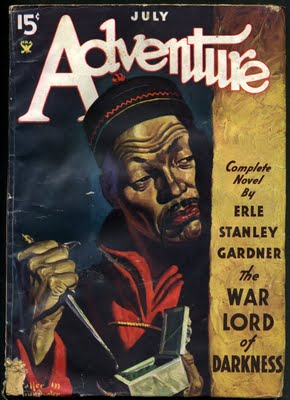

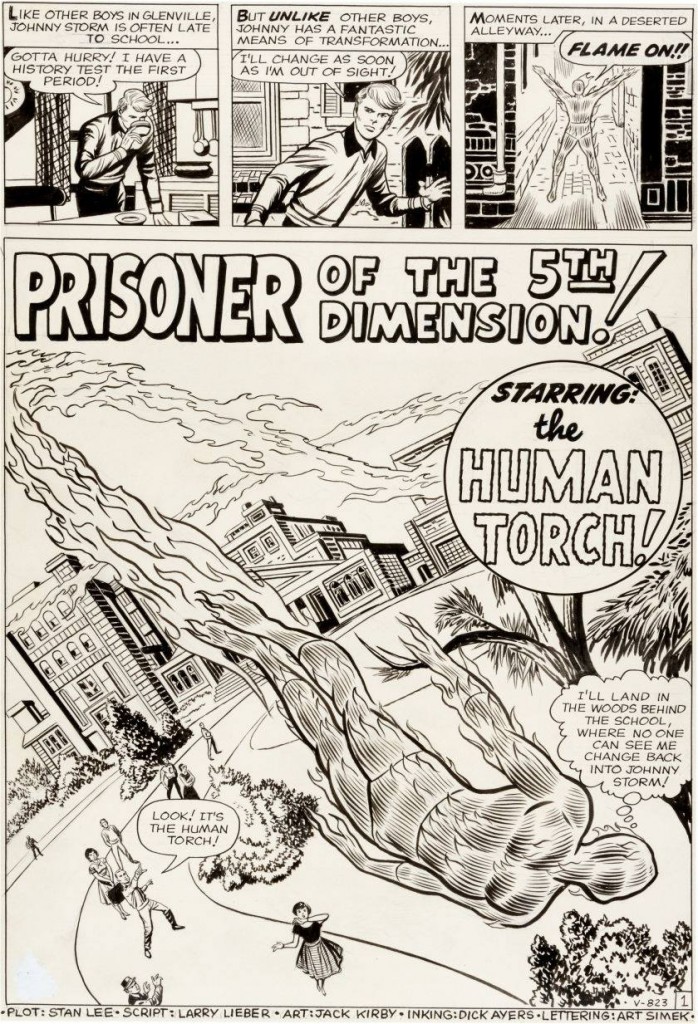

The first comic book packaged by Funnies Inc. was Marvel Comics #1 (Oct.1939) for Timely. It contained the first comic book appearance of the Human Torch, Sub-Mariner, the Angel, Kazar and several others. It quickly sold through its first printing and a second was ordered up. Marvel Comics was renamed Marvel Mystery Comics with issue #2; the series was a hit!

Bill Everett talked about working at Funnies Inc;

Everett: We formed Funnies in an effort to go into business for ourselves, eventually to become publishers. This did not occur. We remained as an art service, and Frank Torpey, who was sort of a contact man for us, got us our first account with Martin Goodman.

I: What was your capacity at Funnies?

Everett: I acted as assistant art director. I assigned story material to artists, accepted it from them, edited it as it came in.

I: What were Lloyd’s duties?

Everett: Pretty much the same as mine, except that he had more authority. He interviewed artists and looked over material and decided if it was acceptable or not.

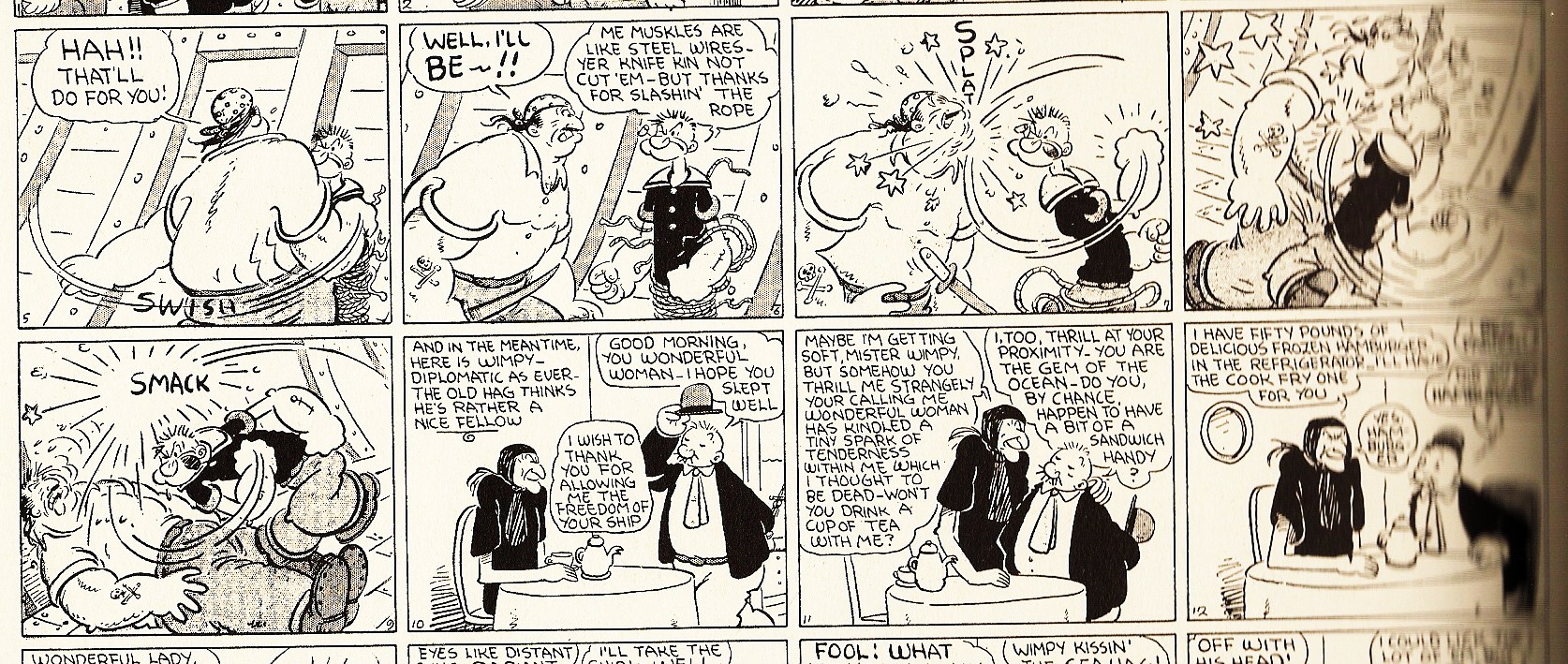

Timely’s top three

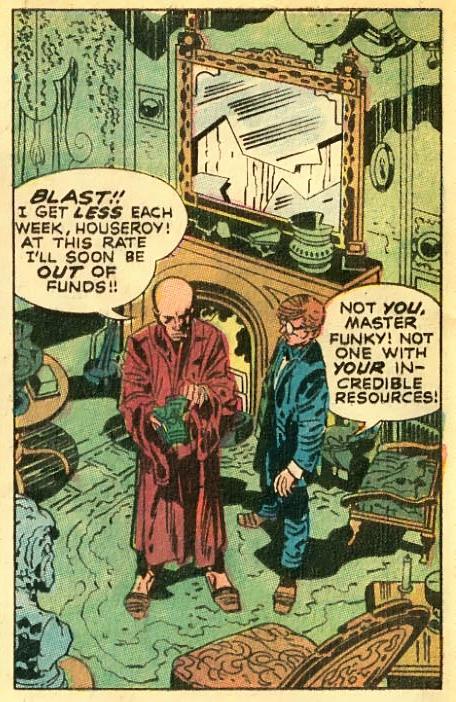

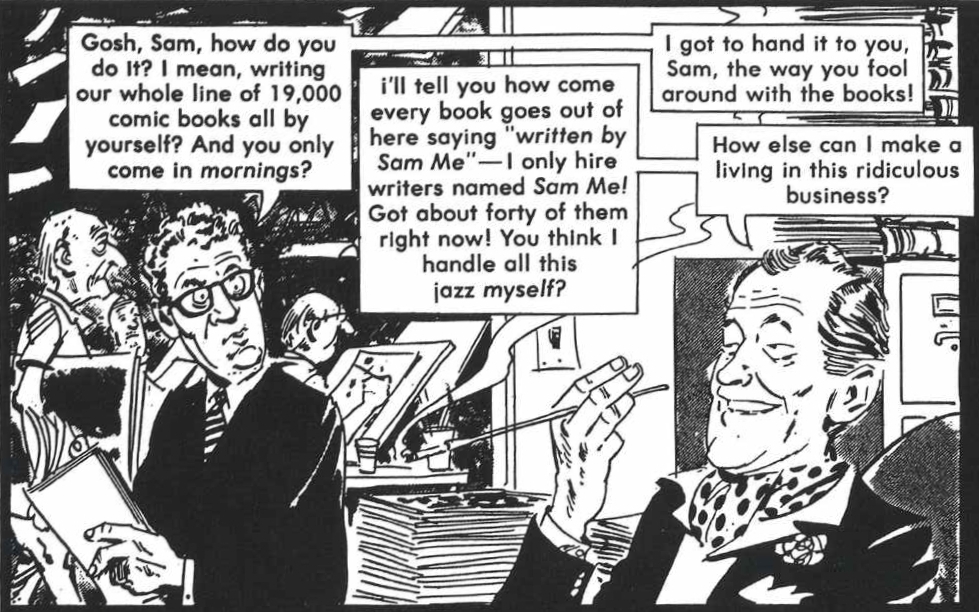

Joe’s timing was perfect; Funnies Inc. was expanding and needed more material. The Colonel explained to Joe how the art studio worked. Bill Everett explained in an interview. “In those days, a new artist would approach us with an idea and a story. If we liked the character and story, we’d buy it. The story would generally be accepted “as is” with very little editing and little change. If a publisher liked it and thought it had a chance of a good sale, then we would continue it for several months until the first sales reports came in—generally about three or four months.” As a former newspaperman, Joe was used to seeing his published work the next day, so he was a little put off when it was explained that there was a 3-4 month gap between the creative aspect and the actual publication. But Joe figured to give it a go, and the Colonel asked for a seven page western. Joe returned 4 days later with his first sequential strip, and it was accepted as is. His next assignment was more daunting. Joe was asked to come up with a new super hero, a lead feature to appear in a new title at Timely. Joe fretted over the assignment and pushed and prodded Jacquet for details. With some exasperation, Jacquet finally responded; “That’s potatoes; just give us the red meat. We don’t have much time.” Joe returned a few days later; the art was crude, the story implausible, the dialogue was laughable, and the lettering, amateurish to be kind–and yet, the Fiery Mask was accepted as presented. Joe learned an important lesson; the owners had no idea, nor cared whether the product was good or bad, they only cared about getting it out on time. It debuted in Daring Mystery Comics #1 (Jan. 1940) as the cover feature, an honor for an anthology strip.

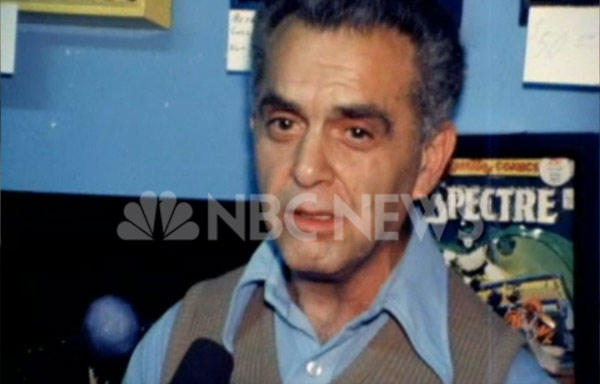

Joe Simon worked directly under the Colonel, and Joe continued to draw stories for Funnies Inc. which would appear in titles for several publishers, such as Solar Patrol for Lev Gleason, and T-Men for Target Comics, from Novelty. But the solitary hours at a drawing board weren’t his chosen ambition. His true interests lay more in the management area of comic production. His newspaper art director background was perfect training for the role of editor for a publishing house since his knowledge encompassed not just the art, but the production side of publishing. Joe knew how to get product out.

Quietly hoping to expand the industry audience beyond the (“twelve year old cretins from Kansas) November of 1938 found Will Eisner meeting up with Henry Martin and Everett Arnold (the owner of Quality Comics)) They had an idea of formatting a weekly comic and inserting it into newspapers. With Will’s rep for producing top-notch material they thought he was the ideal man to produce them. Will agreed, and after a quick separation from Sam Iger he took his pens, brushes and part of the art squad and headed to a new studio in the swank Tudor City complex. From there they would produce the Spirit magazine plus some other features in Arnold’s army of books. Unfortunately this left Fox with some holes to be filled.

In Dec. 1939, Victor Fox placed an ad in the papers looking for artists to replace the ones leaving with Eisner. Simon answered the ad, and met with Victor Fox and Robert Farrell. Joe entered the interview process as a novice comic book artist with a dozen or so stories under his belt, and exited as an editor. First job; George Tuska had left E&I and his two strips needed to be ghosted.

Say hi to Joe Simon – Will Eisner had better ideas

As much as Jack Kirby was impressed by the persona of the new editor, Joe was equally impressed by the talent and speed of the staff artist. Jack was immediately given the task to plug up those couple holes. For the May 1940 issue of Mystery Men Comics, Jack did Wing Turner, a modern day aviation strip. Jack loved airplanes, some of his childhood idols were the barnstormers, and aerial hot shots. One of his fondest memories was when a BBR buddy; Morris Cohen took Jack on a plane ride. Kirby recalls; “We flew upside down over New York City. He scared the hell out of me, but that’s how I got the idea of drawing city scenes from a bird’s eye view.”

Cover for BB#3 Alex Raymond swipe – Simon does Lou Fine beautifully

Jack put a lot of care into this story. The planes are authentic, and the flying scenes are wonderfully staged. Though only three pages, it is also of interest that we are introduced to Prince Otembi, an African Pygmy shown as an intellectual and flying equal to the white American hero, something rarely seen in comics of this period.

Hi-contrast, clean lines – Wing Turner: nice planes and a pygmy

For Science Comics #4 (May 1940), Jack drew “Cosmic” Carson. This had Jack once again doing space opera, and this is really superior work. The futuristic city is straight out of Metropolis, and the weapons are detailed and finely rendered. Kirby’s figures and musculature borrows heavily from Alex Raymond. The one glaring weakness is Jack’s attempt at a femme fatale. The female figure in a form-fitting costume seemed to give Jack fits; he never managed to get the proper mix of sexiness and grace needed to pull this off. I think he needed a real life model. It would come soon enough.

Joe Simon set out to fill in the Fox staff; he would hire Al Harvey for production work, and artists such as Chuck Cuidera, and Al’s Avison and Gabrielle. He would bring in writers Ed Herron and Martin Burstein. Joe took it upon himself to produce all the covers for the Fox books, and using Lou Fine’s style as a template he produced some amazingly detailed and energetic covers. Despite signing many of them, his covers have often been mistaken for Lou Fine. Joe had a knack for mimicry. The bullpen was small but energetic. Chuck Cuidera remembers Jack as the little animated artist who never stopped. He was always grunting and talking and moving while he drew, like a ball of energy trying to explode. Later on Joe would hire Howard Ferguson as letterer. His lettering is found on most strips done in-house at Fox. Joe says he met Ferguson while working over at Timely’s pulp division, but evidence shows he was working for Joe at Fox before he joined Joe at Timely.

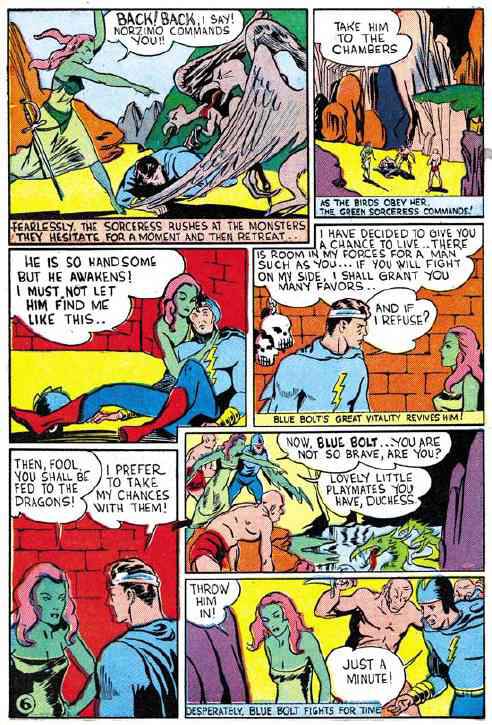

Simon’s Blue Bolt, bad lettering, bad formatting, ugly woman, illogical but ok comics

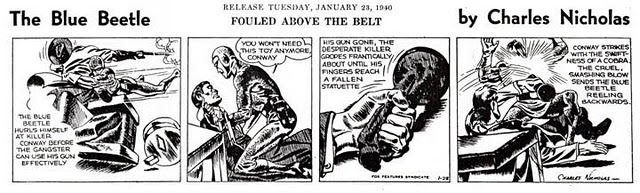

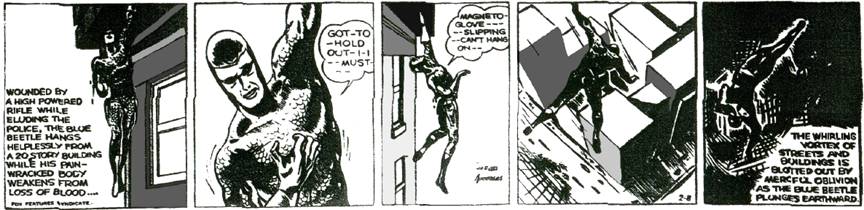

Jack continued on Blue Beetle. Unlike comic books which had a 3-4 month lag, newspaper strips customarily worked on a six week production schedule. The strip began publication on Jan. 8, 1940, and Kirby’s installments ran for 2 months. After the first storyline wrapped up, Louis Cazenueve took over the art chores. One can speculate as to why Kirby was pulled from BB, but what is certain is that Joe Simon had bigger plans for Jack, and Jack was eager to follow. Though Joe was editing for Fox, he continued to freelance with other companies. Joe asked Kirby to assist on his freelance projects, and Jack was pleased to do so. For Worth Publishing, Joe provided 3 covers for Champion Comics #s 8-10. The first was penciled by Joe, but #9 and 10 were penciled by Jack, marking his first original cover art. Joe says that the three covers came about in exchange for the publisher letting Simon and Kirby work there on other features.

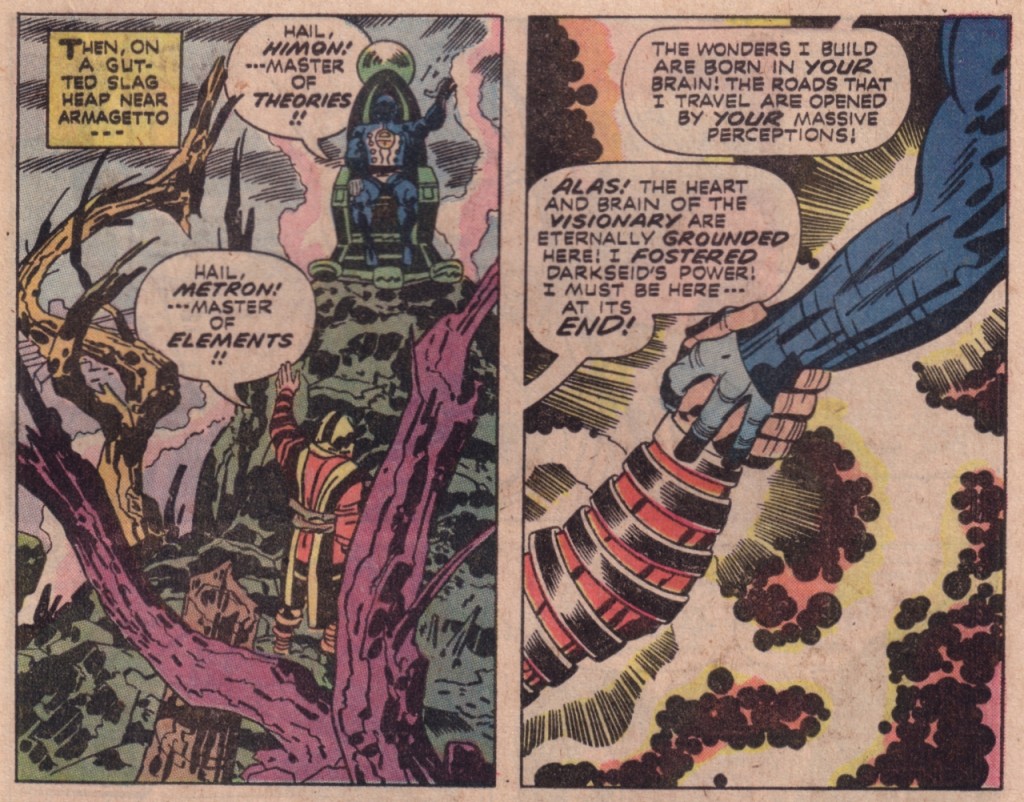

Over at Funnies Inc. Novelty Press had contracted for some comics to add to their magazine line. Novelty was the comic book imprint of Curtis Publishing Company, publisher of The Saturday Evening Post. Although published in Philadelphia, Novelty Press’s editorial offices were in New York City. Art was supplied by Funnies Inc. Target Comics was the first title, and this had featured several strips by Joe. For their second title they chose to name it after the featured character. The first issue of Blue Bolt Comics was dated June 1940. It featured the origin of Blue Bolt, drawn, inked and lettered by Joe Simon. The strip highlighted Joe’s strengths and weaknesses. The concept was a blending of Fox’s Dynamo, and Sorceress of Zoom strips with The Phantom Empire, a Gene Autry western/sci-fi movie serial from 1935.

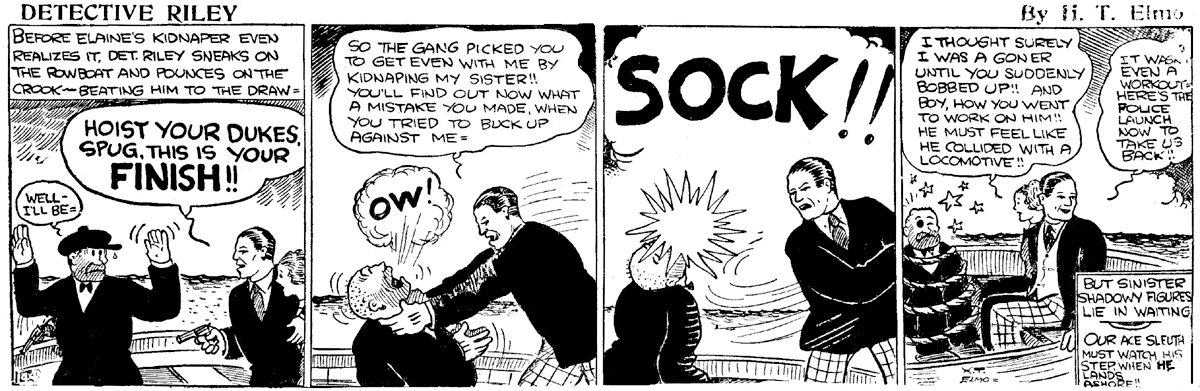

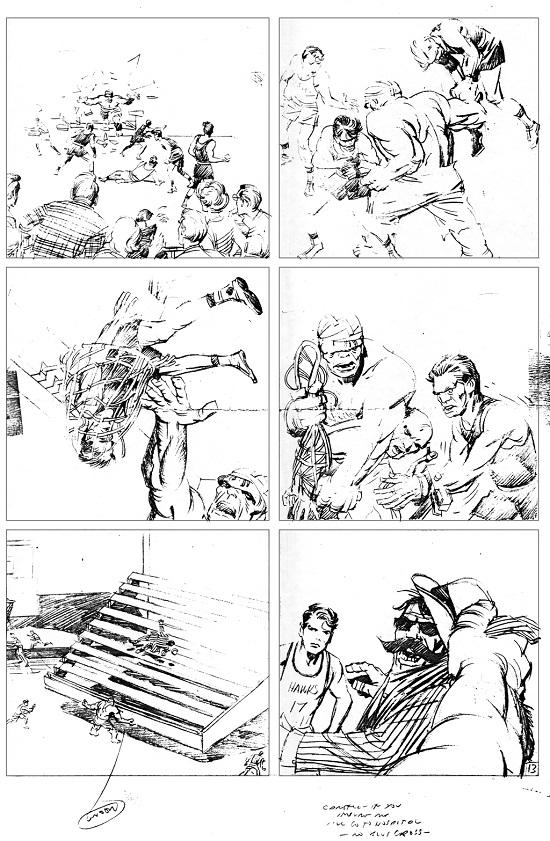

Kirby’s firsts all action skeletal bodies

An interesting advertising blurb appeared in Prize Comics #6. Prize was published by Crestwood a small independent. The cover of Champion Comics #10 was one of Kirby’s first covers. It was drawn for Worth Publishing. I have no evidence of any connection between the two companies except that Simon and Kirby began working for Prize the next issue of Prize Comics. Perhaps it was this early art that sold Prize on S&K. It’s notable to see that Champion Comics #10 was cover dated August but actually hit the stands on June 28. One other oddity is that Prize Comics #6 was dated August, and it wasn’t until December that issue #7 arrived. I don’t know why the four month hiatus, but the content was completely reworked with new characters and updated characters, led by Kirby’s version of Black Owl.

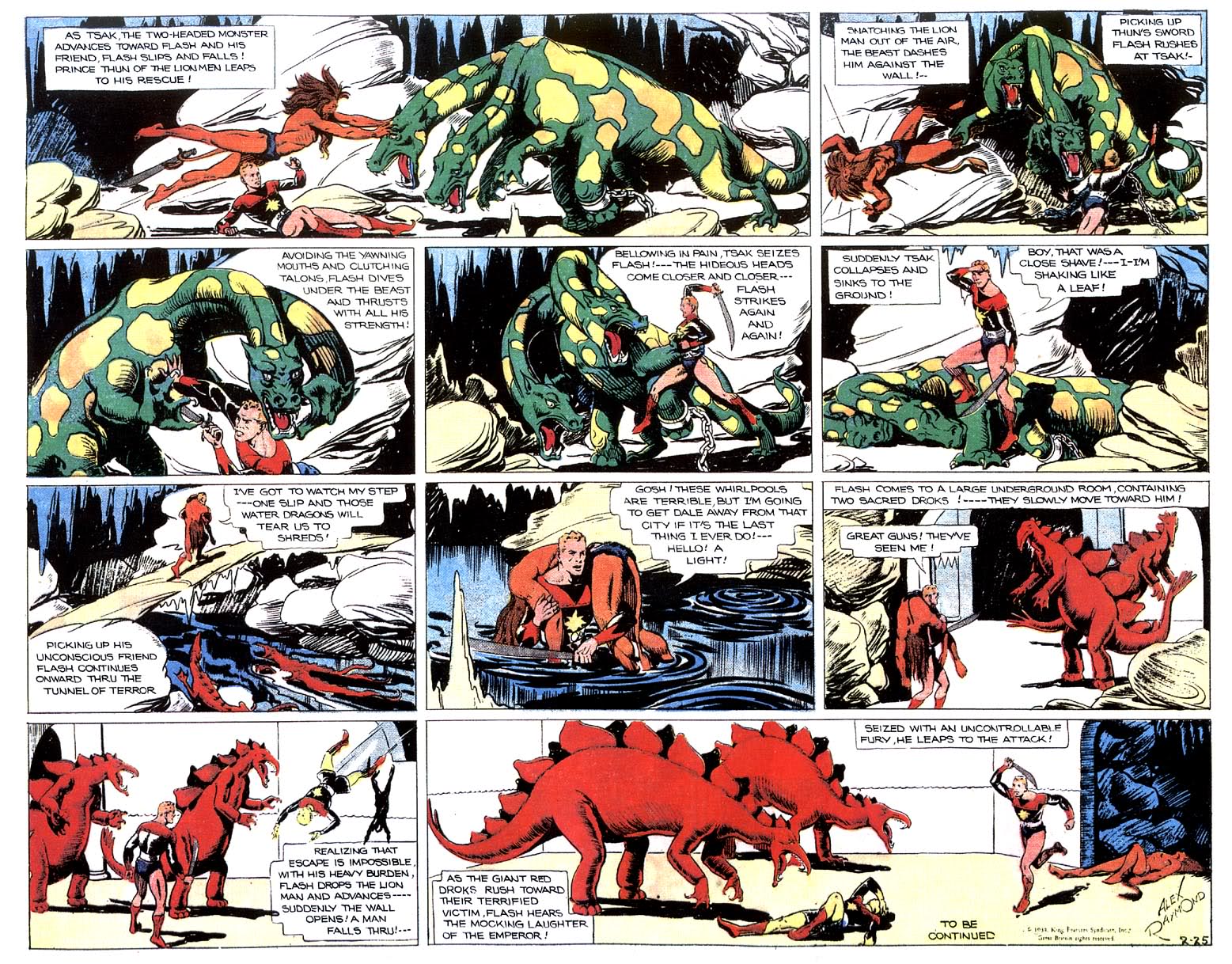

Oh sad eyes don’t worry Blue Bolt to the rescue – Gene goes sci-fi

In Joe’s story, Fred Parrish, a Harvard sports star is mysteriously struck by lightning, and hurled into the underground world of Deltos. Dr Bertoff, a scientist who resides in the underground cavern world revives him with massive doses of radium. The radium had side-effects giving Fred the ability to fly and to harness the power of lightning. Deltos is ablaze in a power struggle against the wizardry and technical superiority of the Green Sorceress, and her Voltor minions. The armies fight, ala Flash Gordon, with an odd mixture of medieval weapons and ray guns, and the Sorceress keeps an eye on the battles via her “televisor.” As drawn the Green Sorceress is a match for the exotically dressed metal bra and diaphanous bloomers of Queen Tika of Murania. (from Phantom Empire) The story unfolds serial style similar to the Gene Autry movie serial.

The concept was acceptable as comic book tripe, but the plot was holier than a hobo’s socks. Joe was good with concepts, but his plotting and pacing skills were weak, likewise he was great with the single photo style page, such as a cover, but very weak in the small sequential panels that make the story flow with a logical continuity. Joe’s background was as a presentation artist, not as a storyteller. To make up for these weaknesses, he relied very heavily on swipes. Many of the panels are direct swipes from Hal Foster or Alex Raymond. All comic artists swiped, but rarely so obviously. Joe realized his weaknesses, and upon arriving at Fox, recognized someone whose strengths were a perfect complement to his weaknesses. Jack’s last three years were spent mastering just those storytelling skills, the pacing and small scenes that kept the story flowing clearly. Plus Jack had developed an art style full of energy and drama, and perhaps most importantly, Jack was fast! Kirby quickly agreed to Joe’s offer to assist on Blue Bolt. In Joe Simon, Kirby saw someone who was at equal ease dealing with management, and art staff. Not since Will Eisner had Jack met someone as comfortable and confident with all sides of production.

Kirby cover-first on Blue Bolt – Joe learns to do better, copy Lou Fine

For Blue Bolt #2, Joe rented a hotel room and after hours at Fox, he and Jack began a collaboration that would become legendary. For this initial effort, they struggled to find a complimentary division of labor. Pages and panels were doled out willy-nilly with both men doing individual pencils and inks. What they got was a schizophrenic jumble where styles competed with each other. The Kirby panels were detailed, dramatic and bold; Joe’s were sketchy and sparse, with little variety in the posing. Very quickly they perfected a system that made the best use of both men’s talents. By issue #4, they would lay out the pages together, and then Jack would pencil, followed by Joe doing the inking. Jack was also helping with the plots, and the stories became stronger with a better handling of the sci-fi aspects.

Separate from Joe Simon, Jack had picked up another freelance job. Famous Funnies had run through the existing inventory of Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider. Robert Farrell approached Jack and asked him to produce new pages of the title. Starting with Famous Funnies #72, (July 1940) and running through most issues to #80, Jack provided 2 pages of art per issue. The art and story is all Kirby. Kirby was solidly in his sci-fi mode, and this once colorless western became a mixture of western lore and futuristic mysticism. The new antagonist was a 50,000 year old man, the last of his race named Chuda, the deathless one! He was a short guy with a huge head- a visual that Kirby would use many times. He could read thoughts, mentally control and incapacitate an enemy, and aurally teleport through walls. The Lone Rider had his hands full. A similar character would appear in Blue Bolt #6 (Nov. 1940), with his big head and mental prowess due to mutation from a blast of cosmic radiation- another theme to be repeated later in Jack’s career.

Jack’s sci-fi western – Eisner’s masterpiece

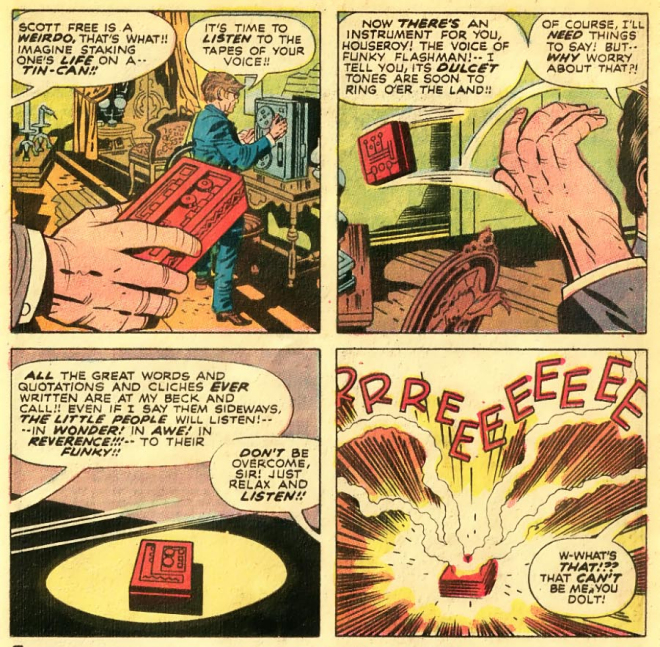

At Fox, Victor was experimenting with a new format; a small four page insert magazine that could be added to Sunday newspapers. The insert would include comics featuring Fox’s stable of characters. The enterprise was short-lived, but the samples show that existing comic book art was reformatted to the different size, and new narrative was added to fill in the story gaps. Jack was assigned to cut and paste up the new pages and write in the new blurbs. His added lettering really stands out on the pages. A month or so later, Will Eisner would have a more successful effort with this format. His new character, the Spirit would become one of the great comic creations of all time. Jack would opine that The Spirit was the best comic creation to come out of the Forties.

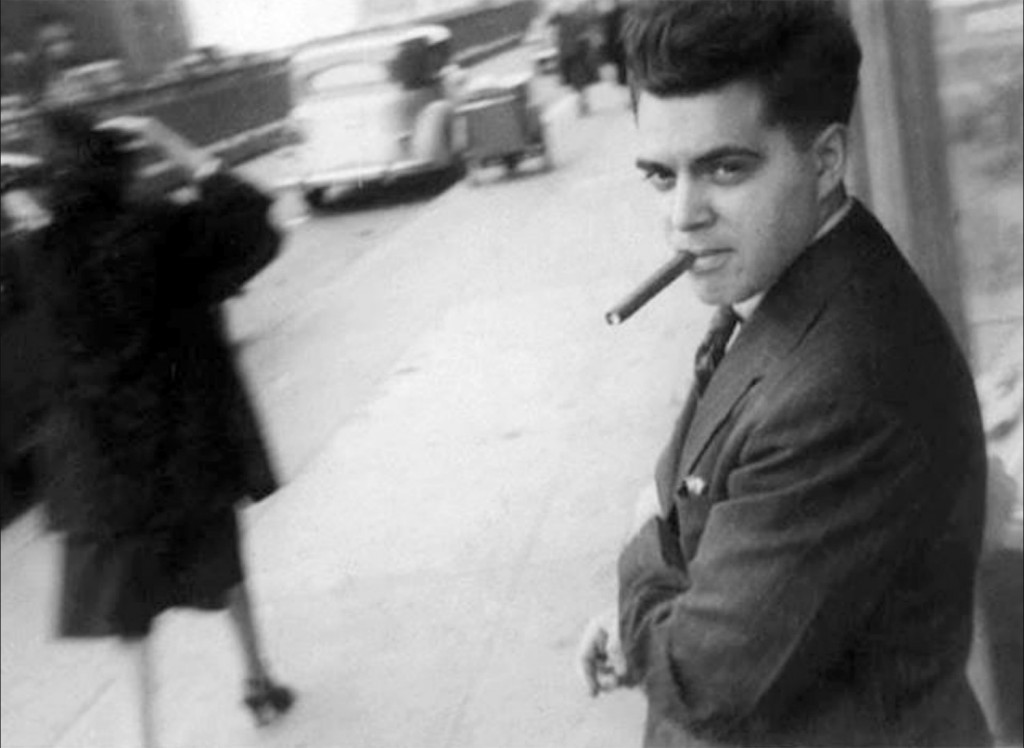

Sometime in March, Joe Simon received a call from Martin Goodman, the owner of Timely Comics. Joe had been supplying him strips through Funnies Inc. for months. Martin Goodman was relatively young, but very worldly having traveled extensively as a young man. He took a job as a salesman for Paul Sampliner’s Independent News alongside Louis Silberkleit, and Maurice Coyne. Goodman, Silberkleit, and Maurice Coyne formed Columbia Publications, one of the earliest publishers of pulp magazines. Goodman left in 1932 and (with borrowed money) found his own company Western Fiction Publishing. His venture into the pulp world was hit and miss. He had no real bombshell, but he did produce a lot of ok sellers. He learned the trick of flooding markets. Goodman had gotten into comics following the Superman gold rush. He quickly hit a rich vein with the release of Funnies Inc. produced Marvel Comics #1, and expanded rapidly. He reached the point where he was confident in the comic business, and decided to begin weaning himself from an art studio. He needed an editor to take over the day to day operations and form an in-house bullpen, and he offered more money than Fox. Joe didn’t hesitate.

Martin Goodman

Red Raven cover swiped from Hal Foster

Joe says that he asked Kirby to join him over at Timely, but Jack balked. The fear of another dead end overwhelmed him. Joe promised him all the work he could want, but Jack needed the security offered by Fox, and was not ready to totally freelance. Jack enjoyed the freelancing but it was very important that Fox not know he was moonlighting, he was afraid that if Victor found out, he would be fired, and nothing worried Jack more than losing his steady salary. Jack would get physically upset when the phone rang for fear it was Victor Fox tracking him down.

Practically a gift! Until you tried to assemble it – valuable collectible today no ads on box

Victor Fox and Bob Farrell had other better ideas. They created an item called the Comicscope, which projected pictures from comic books onto a larger screen. The process was tacky and underwhelming, cheap and flimsy; but they advertised the heck out of them. Besides their own books at Fox, they also advertised in Timely’s (using Captain America) and in Speed Comics (prior to Harvey taking it over) and others. They show up on e-bay occasionally, but the package was so cheap they are often in pieces. Interestingly, the ad featuring Captain America was the earliest use of Cap in advertising. Noted toy and music producer Remington-Morse produced the item. S&K received nothing.

Unexplainably, Victor Fox also created Kooba Cola, a new drinking sensation. Despite the heavy advertising for several years, no actual Cola was ever produced. Urban legend says that Fox simply created the name and concept. He was trying to build demand through his books and then sell a manufacturer the name to cover the created demand. Unfortunately the demand never arose and there were no takers for the name.

Send in them bottle caps—if you can find them

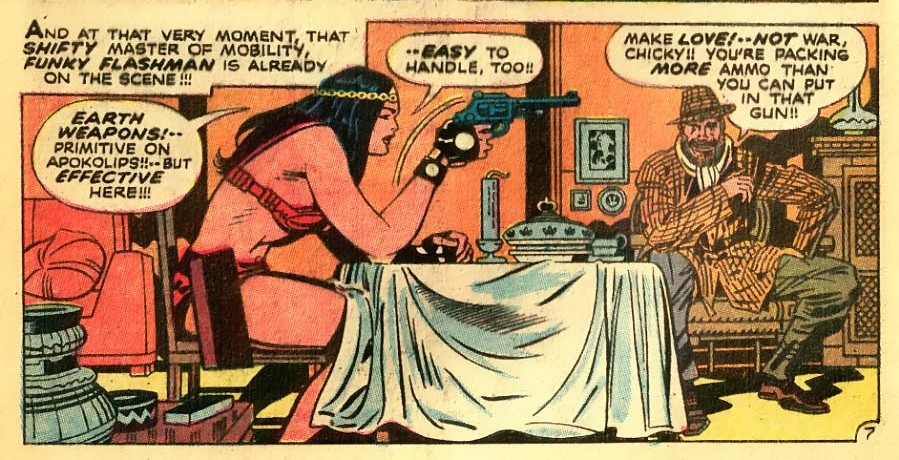

Joe’s first task at Timely was to put together a new title. Joe raided the strips and art staff at Fox. Louis Cazenueve was picked to do the art chores on the title character, a swipe of Fox’s Bird-Man strip named, Red Raven. Dick Briefer came up with a new character named the Human Top, and Kirby was tabbed to do two new strips. Mercury in the 20th Century was written by Martin Burstein, and drawn by Jack. Thematically and graphically swiped from the Fox title Thor, this was the first time Kirby would work the theme of mythological gods coming to Earth to save mankind from evil. As in the Thor strip, this god flew around in his underwear also.

God in his underwear

Mercury was the mythical speed god, sent to Earth to help defend it from Pluto, the Prince of Darkness. Pluto had taken the guise of Rudolph Hendler, the evil dictator of Prussland. This thinly veiled caricature of Adolf Hitler was the first time that Jack Kirby would make Hitler the villain, but it wouldn’t be the last. An excellent introductory tale, the strip showed promise. Jack’s figural work continued to improve, especially his female figures, they were becoming softer and rounder. Both Minerva and Diana are shown as strong yet feminine. Jupiter, as depicted by Jack has long flowing white hair and beard. This template followed Jack forever and appeared whenever he was drawing wise venerable older godly characters.

Simon, or Kirby drew the gorgeous cover to Red Raven #1, with the swooping Red Raven storming the parapet of a castle attempting to save a maiden from villains wearing medieval armor and brandishing swords. It has nothing to do with the interior Red Raven strip which was a modern day story featuring thugs with guns, but curiously understandable in that it was swiped from a Prince Valiant panel. Jack had nothing to do with the Red Raven story and Joe Simon claims that he was laying out the covers, so it may have been Joe who swiped the Prince Valiant panel, and layed it out for Jack to finish

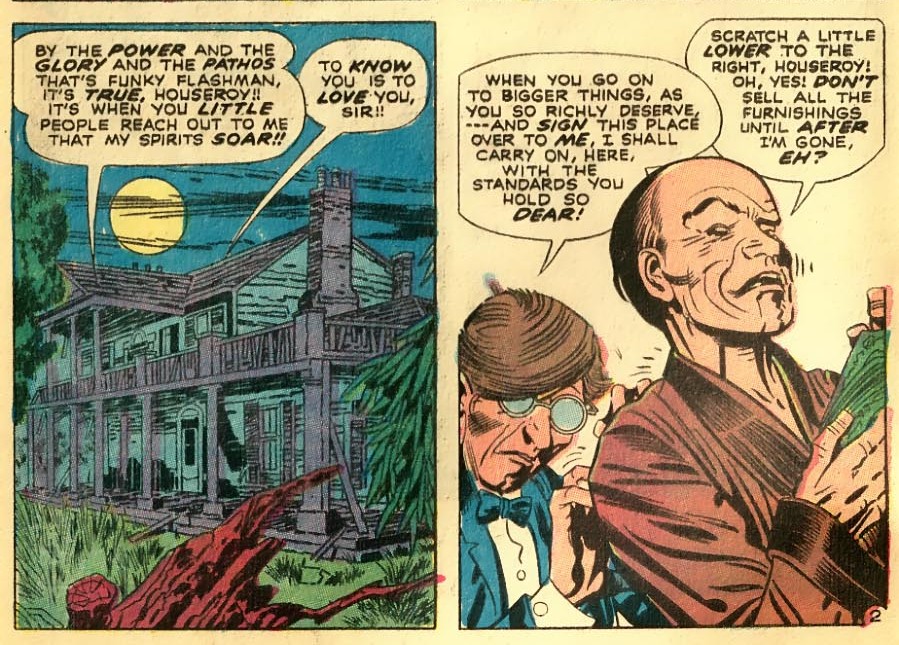

Comet Pierce was another space strip in the Cosmic Carson vein. Beautifully drawn, Jack continued to impress with his machinery and alien vistas. The strip ends with the rakish adventurer joining up with the rebel Queen, promising to help her fight and regain her country’s freedom. This strip was written and drawn by Jack, and more importantly, for the first time, boldly signed on the splash page Jack Kirby!

Two filler strips in Red Raven note signature on second strip Martin Burstein on first was a writer

Joe and Jack were busy working on another character; Marvel Boy was another variation of the gods coming to Earth in times of need theme. Once again it is the specter of Adolf Hitler proclaiming “First Britain, then France and ultimately complete domination of the world is our aim!” This time, instead of the actual god, it is the essence of Hercules that is sent to inhabit the body of a young boy. In a fascinating bit of coincidence, the writer, probably Martin Bursten, makes the same error regarding Valhalla as the home of the gods that the writers of Fox’s Thor strip made. Asgard was the home, Valhalla was heaven. The young boy grows, and on his fourteenth birthday he is visited by an eerie shadow informing him it is time for him to become the “marvel” of his age. With the addition of a colorful suit, the boy begins his personal war against the fifth columnists of Fuehrer Hiller.

This feature appeared in Daring Mystery Comics #6 (Sep. 1940) sporting another wonderful Kirby cover. The premise closely aped the origin of Captain Marvel, a new character from Fawcett, another new comic publisher. Yet it never seemed to raise an eyebrow, of course Fawcett had its own plagiarizing problems, and may have been too preoccupied to notice. It is an interesting use of a black person as a thug on the cover.

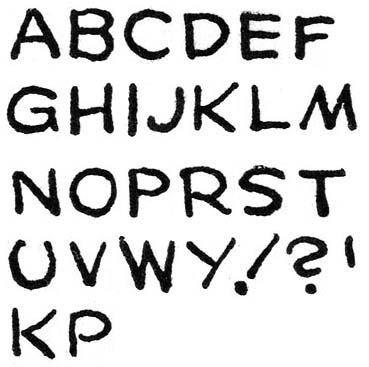

First super-patriot? Atmospheric backgrounds in Fiery Mask

It is always useful when looking at these early Timely efforts to look at the lettering. As a rule, if the job is lettered by Jack Kirby, then the story was produced solely by Jack with Simon strictly as the editor. If the lettering is by another, then it is collaboration, with Simon and Kirby working together. On strips like Blue Bolt, the lettering was always done by Joe until Howard Ferguson came along and took over. Once discovered by Joe, Howard would be the primary letterer for S&K until he died. Howard was considered by many to be the best letterer ever. Mercury and Comet Pierce were lettered by Kirby, and show no Simon assistance. Marvel Boy is interesting because we see Joe’s lettering, but on the prelude where the gods discuss Hercules going to earth, we see Ferguson’s distinctive lettering, leading one to assume that the prelude was actually added last.

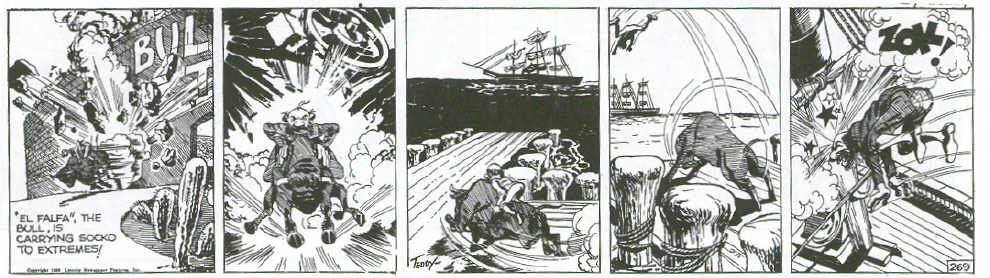

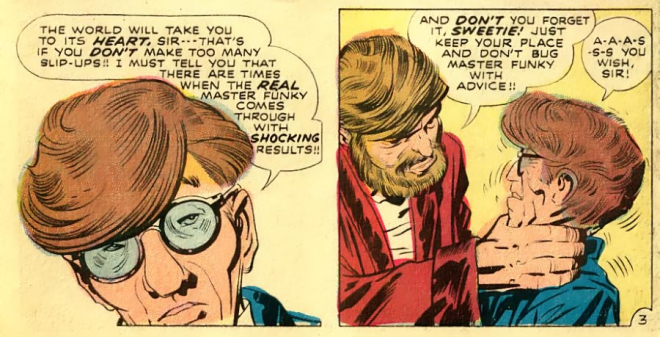

Simon and Kirby also produced another strip for Daring Mystery Comics #6. The Fiery Mask, Joe Simon’s first costumed hero was brought back. In what looks like a very rushed job, the boys reverted back to the methodology from their first collaboration on Blue Bolt; each doing individual pages and then shuffling them together. The result is another schizoid package with the two styles fighting for dominance. What makes it worse is that in the rush, Joe simply swipes Alex Raymond en masse. Even the smallest, least consequential panels are swiped. The cleanup is also poor as lines that should have been erased remain visible. In all fairness, this may be the least professional effort to come from Simon and Kirby, it may also have been an earlier drawn strip and not used till later.

Unfortunately for Jack, Red Raven Comics and Daring Mystery Comics was another promising start turned dead end. Though Jack had already drawn second installments of Mercury, and Comet Pierce, Red Raven was cancelled after only the one issue, and Daring Mystery Comics was put on hiatus. Jack’s wariness about leaving Fox must have looked prescient, or maybe Jack may not have even noticed, his pace never lessened, he continued his work on Blue Bolt and Lightnin’, and his production work at Fox. He picked up a rushed inking job over Fletcher Hanks at Fox. Blue Bolt #5 would feature the debut of a new credit line. Proudly displayed on the splash page for all to see was “by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby”.

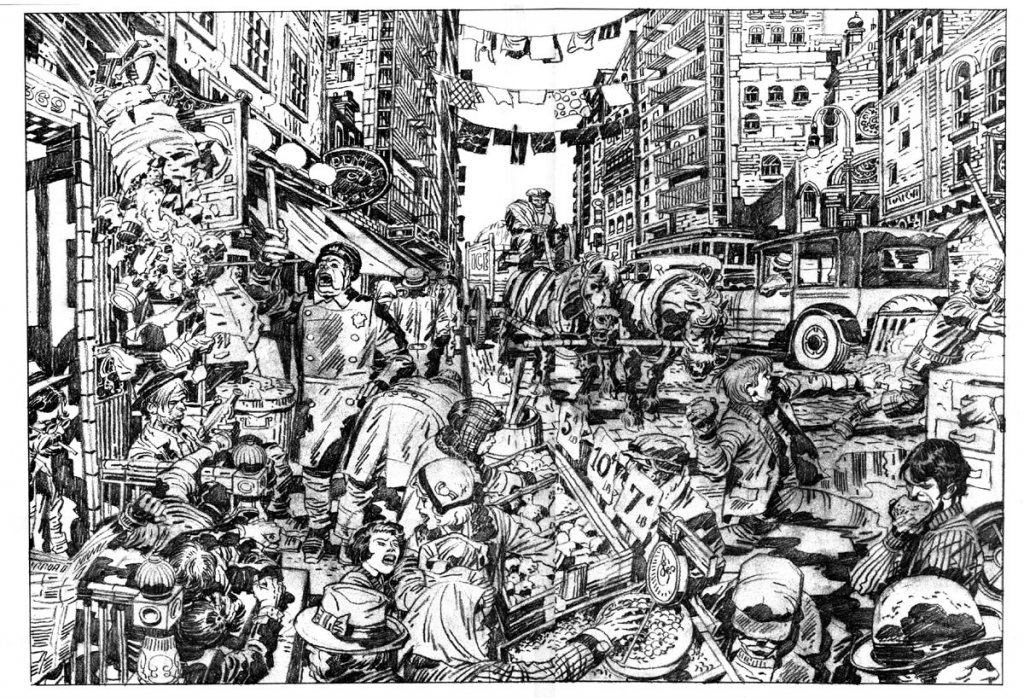

1940 was not yet half over and Jack had never been busier. Joe had kept his promise to give Jack all the work he could want. Goodman needed an art director for his pulp line, and Joe fit the bill. For the next year, Joe and Jack would provide some inspired spot illustrations for the lurid sci-fi, detective and sports magazines. For the pulp illustrations, Jack used a conte crayon. It gave a further depth and range of value to the b&w drawing.

Some of Joe’s table of contents seems ripped right out of Macfadden’s true confessional magazines. More importantly, Joe had procured from Martin Goodman the okay to hire Jack as a salaried full time employee. Joe had assured Martin Goodman that it was an investment well made. Bye-bye to the crazy little man claiming to be the “King of comics” and with the security of Jack’s increased salary the Kurtzberg’s moved to a two story railroad duplex in Brooklyn. Jack would always joke that he had heard a tree grew in Brooklyn—a sly reference to the popular 1943 novel by Betty Smith about an immigrant family coming of age in Brooklyn during the first two decades of the 20th century. Elia Kazan directed the movie version in 1945. Thanks to Joe, Jack had finally gotten out of the Lower East Side, and found his tree.

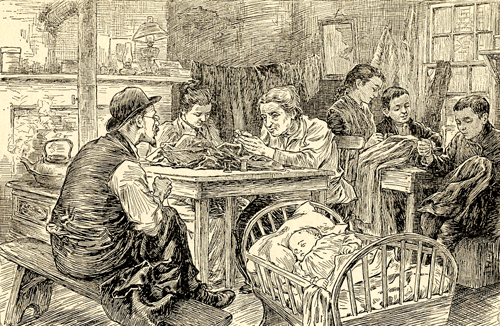

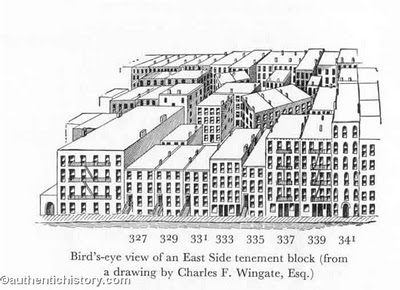

Jacob Riis once again on the resiliency and tendencies of the Jewish ghetto dwellers;

“ As to the poverty, they brought us boundless energy and industry to overcome it. Their slums are offensive, but unlike those of other less energetic races, they are not hopeless unless walled in and made so on the old world plan. They do not rot in their slum, but rising pull it up after them. Nothing stagnates where the Jews are. The Charity Organization people in London said to me two years ago, “The Jews have fairly renovated Whitechapel.” They did not refer to the model buildings of the Rothschilds and fellow philanthropists. They meant the resistless energy of the people, which will not rest content in poverty. It is so in New York. Their slums on the East Side are dark mainly because of the constant influx of a new population ever beginning the old struggle over. The second generation is the last found in those tenements, if indeed it is not already on its way uptown to the Avenue.”

Perhaps not uptown Manhattan, but this second generation Jewish family had gotten out of the Lower East Side, and Brooklyn had trees.

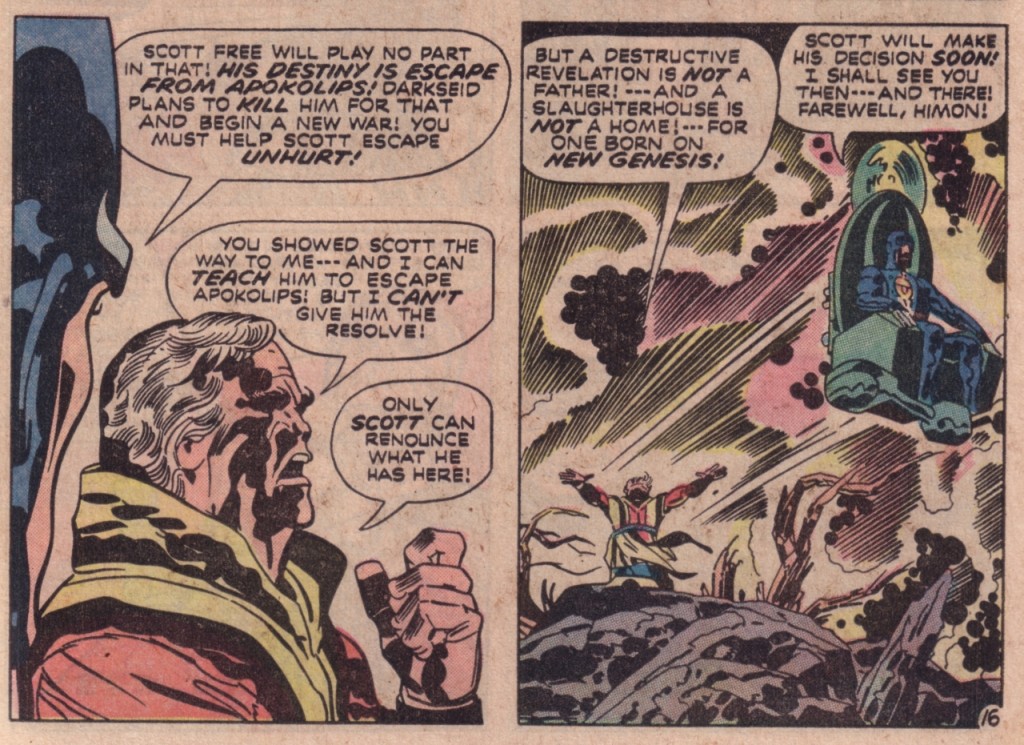

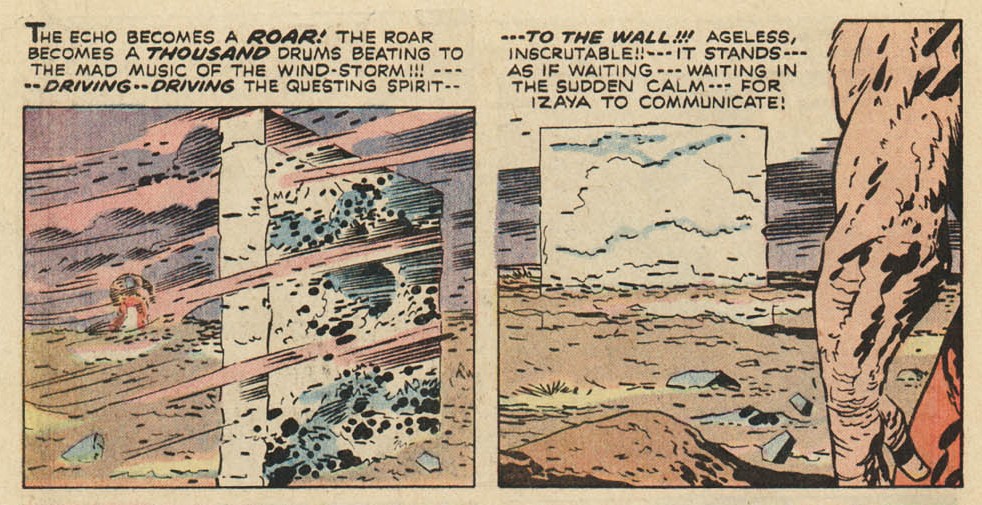

With the cancellation of Red Raven and Daring Mystery, Martin Goodman had contracted his line of titles, focusing on his core characters, but it was still his goal to break away from Jacquet’s studio. Marvel Mystery Comics had always been the exclusive bailiwick of Funnies Inc. but on issue #12, Joe Simon provided a Kirby cover featuring the Angel. In MMC #13, he inserted a new strip from in house–Jack Kirby’s Vision.

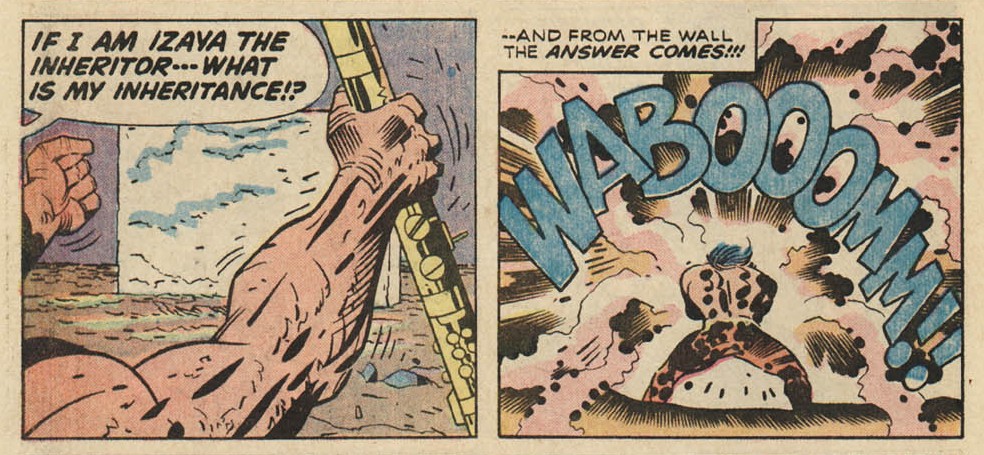

Inspired in part from Fox’s character the Flame, the Vision could travel between dimensions via smoke. A hole had been blasted between dimensions by Prof. Enoch Mason’s dimension smasher. When mobsters tried to shut it down, Aarkus Destroyer of Evil emerges from the smoke portal and with a touch exacts a swift and deadly justice on the goons. While the story was short on logic and characterization, Jack makes up for it by offering wall to wall action.

Spider-Man eyes

MMC #12 cover only – then in #13 – signed pulp art

Jack had fun with the Vision, it was a chance to kick loose, and his art and action scenes showed it. It was atmospheric with dark clouds of billowing smoke everywhere, and cluttered with bodies flying at all angles. As Kirby had matured, his action scenes had stretched and expanded until, borrowing another bit from Lou Fine, the characters could no longer be confined within the panel borders.

Artist Gil Kane talks about Jack’s growth and work ethic on the Vision in an interview with Gary Groth. “Jack told me he used to write, pencil, and ink practically a whole Vision story in one day when he was at Marvel…Six to eight pages. It was unbelievable. It probably took him about two days, but it was a miracle because every job was brilliant. Even if it was casual, it was brilliant. When I take a look at Louie Fine’s stuff now, it just doesn’t compare to what Jack showed continuously, a real level of excellence.”

Jack could never remember many details about the Vision, but he did make one interesting observation.. “The Vision was an occult hero I borrowed his pupiless eyes for Spider-Man”, perhaps the earliest mention of any connection between Jack and the wallcrawler. True or not, he did have pupiless, dark rimmed eyes.

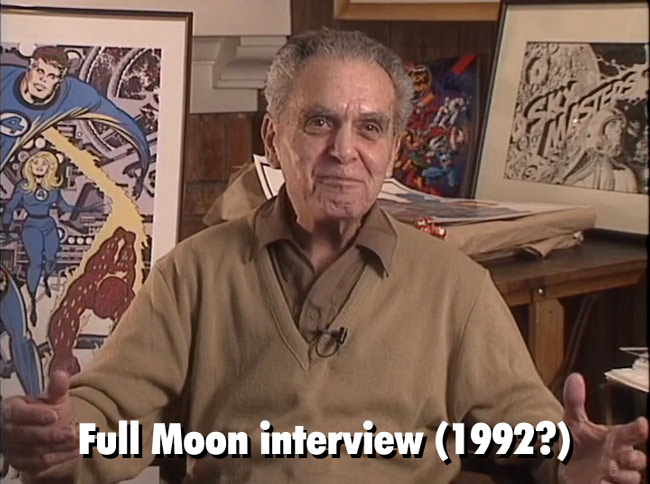

June 1940 came in hot and sticky. Hyman and Lena moved into the apartment upstairs from the Kurtzberg’s with their family. Like the Kurtzberg’s below, they were immigrants from East Europe, specifically Russia. The Goldstein father struggled resulting in constant moves from apt. to apt. While unloading belongings, 17 year old Rosalind Goldstein noticed a stocky, shirtless young man playing stickball in the street, and debated with her cousin over who would get him first. When Jack saw the dark haired beauty with the flashing eyes and beguiling smile there would be no contest. Rosalind, born Sept. 25, 1922, had been sickly as a child, suffering from the effects of asthma. The family often feared for her life as she wheezed and gasped for air. It had only been the recent widespread development of inhaled adrenaline (epinephrine) to treat asthma that doctors had been able to control the symptoms. With better health, she had begun to bloom into womanhood, the very definition of houris. Attention from boys was something new for her. They talked for a while and Jack asked Roz–as she was called–if she wanted to see his artwork. Roz thought it was a smooth line, but with both sets of parents nearby, she saw no harm in pursuing it. Jack impressed her with the pages of art he was working on. In fact, Jack impressed her whole family. Like most Depression families, a man with a full time job was to be admired, and one who was helping support his family was to be treasured. Jack says it was love at first site, Roz wasn’t so sure. Jack loved to tell stories about chasing rival suitors away from Roz, even threatening to break the fingers of a piano playing rival. Jack’s protectionism also extended to Roz’s sister Anita, he would chase away her many suitors. Roz says all the neighborhood girls were after Jack.

Sinatra at the Paramount – cheap dates

Time and money were tight, but Jack and Roz managed to squeeze in dates; like going to the New York World’s Fair; perhaps to see the first polarized, Technicolor, stop-motion animated 3D movie, directed by John Norling. The film was called “In Tune with Tomorrow” and it was a centerpiece of the Chrysler Pavilion. They also liked going to the movies, or simply taking walks.

Chrysler in 3D

One of their favorite sites was the Paramount Theater to dance to Frank Sinatra or one of the big bands. They would talk till three in the morning in the Kirby’s parlor room until Mr. Goldstein would happen by emptying garbage or some other ruse. On Sept. 25th, 1940, Roz’s 18th birthday, Jack proposed, she accepted.

just before the wedding – The center of the 1939 Universe

Life continued on as usual, Joe and Jack continued their back breaking pace. The pattern was pretty much set. Joe would edit, and co-write the stories, Jack would be the primary penciller while Joe, and others would do the inking. Charles Nicholas would be the main inker. Jack or Joe would occasionally beef up the inks to maintain consistency. Joe claims that one day he walked in as Kirby was erasing some lines. Horrified, Joe told Kirby never to erase- any corrections could be made during the inking phase, and Jack’s time as penciller was too valuable. Jack had come to grips with the idea of being just one part of an assembly line production crew. It would be the rare job where Kirby would both pencil and ink, and even rarer when he would letter.

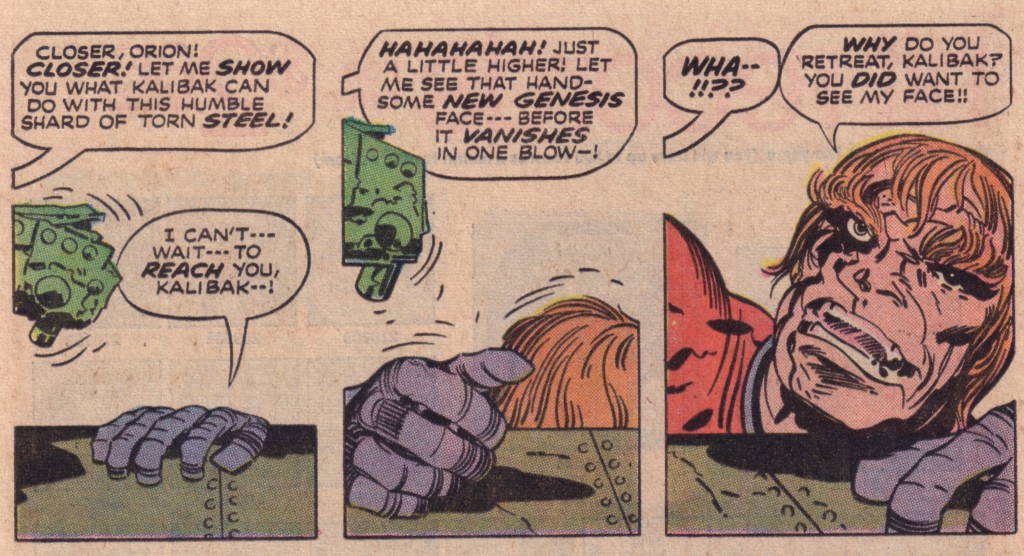

Joe never rested; despite the increased load at Timely, he continued to look for freelance work. Every week would bring a new request from some publisher for a new character or a quick fill-in issue. Crestwood Publications was looking to revamp their main title. The first six issues of Prize Comics had cover featured an uninspiring character named Power Nelson. The series lacked any strong focus. Prize Comics #7, sported one of Kirby’s best covers to date, it featured an update of the character Black Owl, changing him from a suave tuxedoed detective into a form fitting long underwear masked vigilante. Dick Briefer would introduce his most famous strip Frankenstein, and The Green Lama by Mac Raboy would also debut. Prize Comics now had a focus. Black Owl would continue for a lengthy run. Jack’s tenure would last only 3 issues. In issues #8-9, in addition to the Black Owl, Kirby would also pencil Ted O’Neil – an aviation strip about an American pilot in the Royal Air Force and his sidekick. With Britain in a declared war against Germany, Jack finally got a chance to smack down the Nazis by name. In a scene reminiscent of Jacob Kurtzberg’s childhood hunchback friend, as a good luck token, Ted O’Neil has to kick Hinky, the stocky little Cockney sidekick in the seat of his pants before each flight. The character lasted many an issue.

France “Ed” Herron, a writer hired by Joe Simon while at Fox, had moved on. He became an editor over at Fawcett Publications. Fawcett was an old line publisher who started with a bawdy joke magazine Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang in 1919. Other racy magazines like Ballyhoo, and Smokehouse followed. Later, they expanded into pulps, but Mechanix Illustrated would become the flagship title. In 1939, the company diversified and established a comics line. Roscoe Fawcett, son of the owner, following the new trend, told his editor to give him a Superman, only make his alter ego a boy. Writer Bill Parker and artist C.C. Beck put their heads together and came up with Captain Marvel -The mightiest Boy Scout to ever grace a four color magazine! With the publication of Whiz Comics #2, (Feb. 1940) Captain Marvel was an immediate hit. Owner Wilford Hamilton Fawcett died in Feb 1940, but his sons would continue and build on the line.

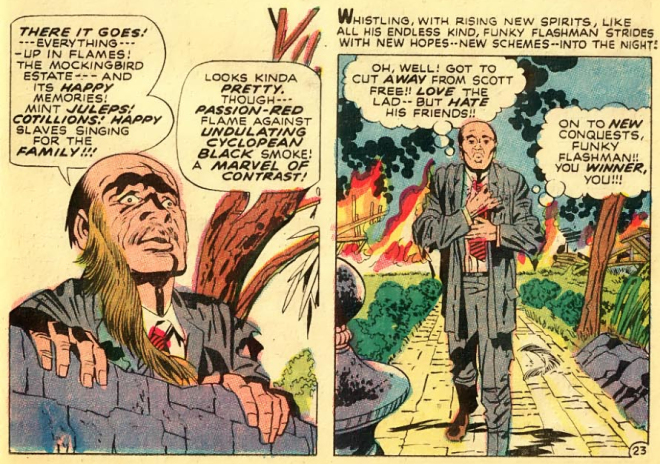

Fawcett kept expanding, and for a new title, Ed Herron possibly contacted his old friends from Fox for help, it’s also possible that Herron took this scripted artwork with him as part of his resume. It’s by Jack Kirby and centers on a masked vigilante and takes place in a mythical Gotham City. It is possible that it was culled from some pages left over from Blue Beetle, or still, another concept from his unsold portfolio. As published, Mr. Scarlet is a combination of new art and reformatted strips. The header, added later, is the only panel that Jack Kirby spelled out Mister Scarlet. In the story panels the original name of the character has been erased and Mr. Scarlet written in by a different hand. There are several narrative boxes pasted over with lettering by Joe Simon. It would be interesting to know what the original name was. A lackluster effort, Mister Scarlet was the cover feature for WOW Comics #1. It was on the streets Dec. 13th, 1940. The character would continue for years drawn by many other artists. This was the first comic use of Gotham City. Later it was stolen by Batman writer Bill Fingers as a literary code for Manhattan so as not to let Batman be stuck in one real city. It is interesting that Gotham City became a nickname for New York City as a means of loathing and lampooning by noted author Washington Irving. It originally meant “home of the goats” and was meant as a place of morons and imbeciles.

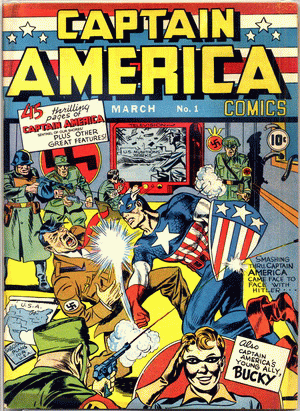

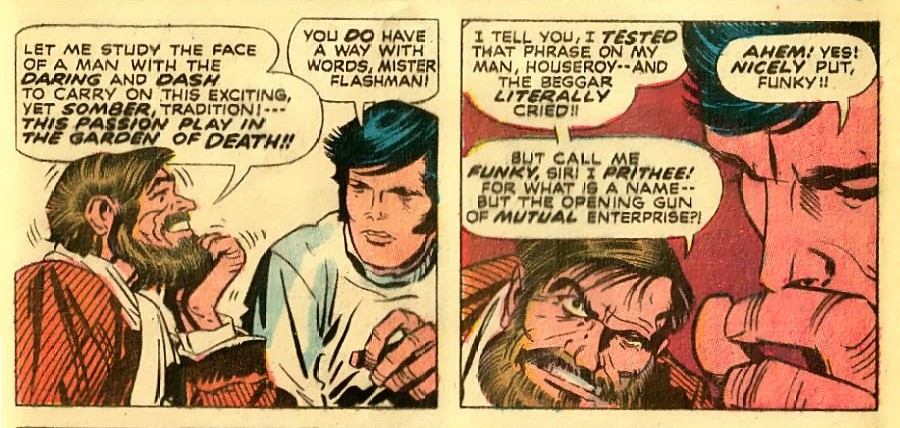

Martin Goodman’s story as to how Captain America came to be is that he wanted a “patriotic” hero to stand up to Hitler. His titles had been bashing the Nazi’s since early 1940, and it was time to personify it. He shopped the idea around and Joe Simon’s interpretation was accepted.

Joe Simon says that he had been fooling around with the idea for a while, coming at it from the opposite tack. Joe was thinking of a good villain. “Then the idea struck home: here was the arch villain of all time. Adolf Hitler and his Gestapo bully boys were real. There had never been a truly believable villain in comics. But Adolf was live, hated by more than half the world. What a natural foil he was, with his comical mustache, the ridiculous cowlick, his swaggering, goose stepping minions eager to jump out of a plane if their mad little leader ordered it. I could smell a winner. All that was left to do was to devise a long underwear hero to stand up to him.”

The truth probably lies somewhere in between. The idea of a patriotic hero was not revolutionary by this time, and neither was Hitler as a villain. Archie Comics had produced a patriotic hero months earlier. The Shield was a red, white and blue garbed government agent who started hunting down saboteurs and spies (and the occasional mad scientist and mobster) in the pages of Pep Comics #1( Jan 1940). Even Simon and Kirby’s Marvel Boy could be considered a patriotic hero as his reason for being was to fight the minions of the Fuehrer and sported a nifty red, white and blue costume. Many companies had been using fictionalized versions of Hitler in their books for months.

Jack’s memory is simpler. “Goodman wanted a new super-hero and we gave him one. Joe had an apartment on Riverside Drive, and we worked on him one night. It was a time when we knew we were all going to be drafted.” As a side note, the conscription bill, after a short period of debate, passed Congress on September 16, 1940.

After looking at Joe’s presentation sketch, Goodman gleefully gave the go ahead, going so far as to have Cap introduced in his own title. Joe had a feeling this could be big, so he asked for a percentage. After some haggling, Goodman offered 25% of the profit, split between Joe and the artists. Joe agreed and Martin had one last request, and that was to rush this to print. “The bastard is live and in the center of an explosive situation”. Martin continued, “He could get killed.” Joe agreed.

Rabbi Simcha Weinsein in his book Up, Up and Oy Vey! How Jewish culture and values helped shape the comic book superhero

“Kirby and his partner, Joe Simon, worked at Martin Goodman’s Timely Comics, where the mostly Jewish staff openly despised Hitler. When Goodman saw the preliminary sketches for Captain America, he immediately gave Kirby and Simon their own comic book. The character was an instant hit, selling almost one million copies an issue. “The U.S. hadn’t yet entered the war when Jack and I did Captain America, so maybe he was our way of lashing out at the Nazi menace. Evidently, Captain America symbolized the American people’s sentiments.” Simon later commented.

Joe decided that the quickest way to get this done was to get a team working on it. He had met Al Avison and Al Gabriele and knew their talents blended well and matched up with Kirby’s style. Jack would have none of this and told Joe that he would make deadline. Joe acceded to his wishes and Kirby got to work. Joe and Jack worked out the script and pacing right on the drawing boards and Jack provided the pencils. The inks were handed off to several artists, among them Al Liederman, a newspaper cartoonist from Joe’s past. Jack punched up some of the inks to maintain quality and uniformity. The cover left no doubt as to what this new book was about; Captain America braving a hail of bullets to deliver a haymaker on Der Fuehrer’s weak chin. America strikes back! No dilly dallying, Hitler and Nazis by name!

Captain America was Steve Rogers, a 98lb. weakling rejected by the draft board. He is recruited by a Government agency to take part in a scientific experiment, one that if successful would create a race of super-soldiers to fight Hitler. After being injected with a secret chemical extract, his body builds to super human muscularity and his mind and reflexes have increased to “an amazing degree”. (It is interesting to note that it was while Joe Simon was editor at Fox that the Blue Beetle also became a super hero by way of a chemical serum) In true comic book tradition, there is a Nazi saboteur hidden in the lab who kills the Professor and the formula is lost to the ages. Rogers swoops in and with a single blow sends the spy flying into some electrical equipment, exacting a deadly vengeance. Donning a red, white and blue costume with a star on his chest, little wings on his temples, and brandishing an invulnerable shield, he is sent off to search and destroy the enemies of the free world. Along the way, he picks up a pint sized sidekick named Bucky. Quickly bypassing Private, Sergeant, Corporal or Lieutenant, he is promoted to a Captain, thus is born America’s greatest hero.

Captain America #1 had two back up strips by Jack Kirby. The first was called Hurricane. It is the Mercury story originally scheduled for Red Raven #2. When that title was cancelled, the story was set aside. Why the character was renamed is unknown, though Centaur Publications had introduced Mercury the speed God as part of an ongoing comic title a couple months earlier. With some retooling, Mercury- son of Jupiter became Hurricane-son of Thor, god of thunder, and the last descendent of the ancient Greek immortals. The fact that Thor was a Norse God rather than a Greek one is a minor quibble. They forgot to change the human name used by the hero, Mike Curry (Mercury) until issue #2 when it became Michael Gray. Jack would also provide the Hurricane story in issue #2.

Hurricane son of somebody – Tuk hairless boy

The second strip was Tuk, Caveboy, an adventure strip set in a prehistoric era when cavemen fought for supremacy over the wild animals. This was beautifully penciled, lettered and inked by Kirby. At this period, as a rule, Jack did not have time to do his own inking and Ferguson was doing all the lettering, which may be a sign that this also was an earlier story taken from inventory- perhaps meant for Red Raven #2, or Daring Mystery Comics. Though cover dated March 1941, Captain America #1 was on the stands Dec. 20th 1940, just in time for the Christmas dimes.

Soon after Simon and Kirby begat Captain America, Ed Herron called on them again. It seems that Fawcett’s Captain Marvel had gone ballistic; the sales demanded that he get his own title. A one-shot titled Special Edition had been rushed out and sold well. Bill Finger and C.C. Beck didn’t have time to do another title, so Ed Herron was tasked with assembling the new book. On Ed’s recommendation, Al Allard, Fawcett’s art director met with Joe and Jack and asked if they could do the artwork. This was an impossible job, consisting of 62 pages of art on a character they weren’t familiar with, in a cartoony style that was opposite their norm, and a two week deadline. Not wanting to embarrass their friend Ed, and after the promise of a bonus, they agreed–just another day in the park.

With Simon and Kirby’s new contracts at Timely, it was important to keep this job hidden, Joe once again rented a hotel room, and after the long hours at Timely’s studio, a small group would gather and work all night producing the stories. Ed Herron would work out the stories with Jack and Joe as they laid them out directly on the boards, and then Jack would pencil the pages, and pass them off to Dick Briefer, among others, to ink. The lettering was done by an unknown hand, perhaps a Fawcett regular. Jack almost got caught drawing a Captain Marvel page while supposedly working on a Captain America page at the Timely office.

The demand was incredible. When asked about this time frame, Jack’s first response was always the same, “The pressure was tremendous. I was penciling at a breakneck speed, as many as nine pages a day. I guess that was the reason my figure work began to take on a distorted look; my instincts told me that a figure had to be extreme to have power.” Jack was seeing Captains in his nightmares, when he had time to get a few hours of sleep. The stress was beginning to take its toll. The daytime hours at Timely, and the all-nighters working on Captain Marvel, were agonizing. They were eating on the run and if possible, catching a few hours sleep on a littered bed in the smoky, seedy hotel. After little more than a week of unending toil, the boys finished. The job was rushed, and the finished sheen wasn’t up to their usual standards, but it was certainly an acceptable aping of Beck’s disarmingly simple style. Given the choice between signing the work or not, they demurred. The first issue of Captain Marvel’s Adventures hit the stands on Jan. 16, 1941. The series would soon rival Superman as the top selling comic character. As an aside; DC Comics would sue Fawcett Publications over copyright infringement in 1941. When Simon and Kirby started working for DC, they were questioned by famed attorney Louis Nizer about their role in the early creation of Captain Marvel. There wasn’t much they could say since they hadn’t been involved with the creation of the character, but none the less, Joe Simon was called as a witness when the case finally went to trial in 1948.

After the production of Captain Marvel, all freelancing would cease. The Blue Bolt serial storyline was quickly wrapped up in issue #10, with the Green Goddess meeting up with the surface people. Kirby’s Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider ended mid story with another artist finishing the tale. Coincidently, a small movie studio Producers Releasing Corp. released the first of 17 movies starring George Huston as the Lone Rider in early 1941. This Lone Rider and his horse Lightning appeared for three years on the big screen.

There was another job produced for Timely in 1940 and was seen in the newly reinstated Daring Mystery Comics #7 (Apr.1941). Captain Daring in the Underground Empire sounds like a Blue Bolt spin-off, but in reality it was the reworked second installment from Comet Pierce, last seen in Red Raven #1 That lone story had ended with the hero promising the beautiful Queen to help her regain her throne, and free her people. This story was that fight for freedom, but for Daring Mystery it was changed to a perplexing tale of futuristic marines fighting a Nazi-inspired army. Comet Pierce and the Queen were now Captain Daring and Secret Service Agent Susan Parker. In the final panel, after the victory Captain Daring addresses the crowd, and embracing Susan says, “I love your Queen.” Oops! It was a literary mess, but the art was wonderful.

The Timely bullpen was growing with the addition of Syd Shores, and Al’s Avison and Gabriele. Syd recalled, “Jack Kirby influenced my sense of dramatics. Jack Kirby influences everybody in comics, though: Before I got really started in the field it was Alex Raymond and Hal Foster, they were my gods back then, but Kirby was the most immediate influence. My comic book career started as an inker to Jack Kirby’s pencils. I think working with Jack influenced my work more than anyone else.”

In late 1940, Joe was asked to find the nephew of Martin Goodman’s wife a job. Starting as gofer, office boy, and all round pest, the 17-year-old Stanley Lieber would soon be put to work writing the 2-page text stories that had to appear in periodicals. In Captain America #3, the comic writing career of Stan Lee officially began. For Jack’s part, the young boy was a pain. Joe told an audience that “he’d sit there while Jack was working, while we were all working. He’d sit in the corner with a flute, and he’d play the flute. Jack and the guys would throw things at him. Finally, to give him something to do, we told him he could …every comic book had to have a page of text to get second class mailing privileges, which are not that important today. But it would take three issues for a publication to be credited with the mailing privilege; then the publisher would get money back from the Post Office. So it was very important to get that mailing privilege- and to qualify you had to have a page of text. So we gave Stan some of the text to do. Nobody wanted to do that stuff because nobody read it-and so Stan did it, and he treated it like it was the great American novel.”

Stan’s memory is a little hazy, but he says Timely at the time was a lot of fun. His role tended towards the mundane- -he says he was the gofer. “In those days they dipped the pen in ink, I had to make sure the inkwells were filled,” said Lee. “I went down and got them their lunch, I did proofreading, I erased the pencils from the finished pages for them. Whatever had to be done. I remember Jack would always be sitting at a table puffing on his cigar, kind of talking to himself as he was doing those pages.”

The long scrambling was over, Jack had found his team. It was a year that had started with little prospect of Jack being called up, and ended with Kirby not only in the majors, but at the top of the rookie class. Joe Simon and Jack Kirby had become the hot battery tandem, each feeding off the others drive, talent and intensity. A year that began with Jack alone fighting his personal demons in a small cubicle, ended with Jack and his beloved Roz planning a future together. They worked like mad people to reach this peak, and they were determined to stay on top.

Previous – 3. Escape To New York | top | Next – 5. Making It Personal