Yesterday, I posted on the Museum’s home page the sad news that Stan Taylor had passed away on the 18th of December. I thought I’d pay him a little tribute by posting his Spider-man essay here, with thanks to his widow, Annabelle. – Rand

Who created Spider-Man? One of the great comic book fanboy debate topics — utterly fascinating because of the three distinct and passionate personalities involved, each having rabid fans ready to lay waste to any who would deny that their favorite was the true creative genius behind this pivotal character. Ultimately, of course, it’s a futile exercise of mental masturbation because we are powerless to do anything about it, even if we could prove it one way or the other. However, not being averse to masturbation, I am going to weigh in with my opinion.

A LITTLE HISTORY

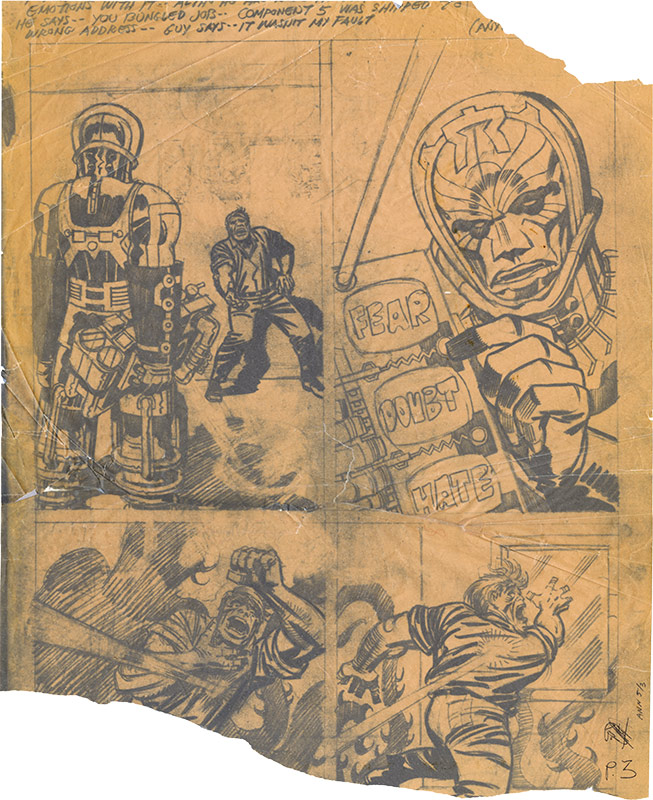

Jack Kirby has stated clearly time and again that he created Spider-Man, most adamantly in an interview conducted by Will Eisner, and printed in issue #39 of Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine,. (Kitchen Sink Pub. Feb.1982). Kirby maintained his claim even when close friends and assistants advised him not to pursue it. Can he be believed? Well, his memory was spotty, and he has made other claims that have clearly been shown to be wrong. So as a witness, he leaves room for doubt.

Stan Lee says “all the concepts were mine” (Village Voice, Vol.32 #49, Dec. 1987). It is his contention that he singly produced a script, offered it to Jack Kirby, and when he didn’t like the look of Kirby’s rendition, he then offered it to Steve Ditko. Can he be believed? Not really. Stan would go so far (or stoop so low!) as to claim that a minor character named The Living Eraser from Tales to Astonish #49 was his creation This character, had the dubious distinction of being able to wave people out of existence with a swipe of his hand. “I got a big kick out of it when I dreamed up that idea,” Lee is quoted as saying (Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics, pg. 97). He then further embellishes this tale by stating how hard it was to come up with an explanation for this power. The fact is, this ignoble power and explanation, first appear in a Jack Kirby story from Black Cat Mystic #59 (Harvey Publications, Sept. 1957). If Lee will take credit for an obvious minor Kirby creation such as The Living Eraser, which nobody cares about, then he certainly would take credit for another’s creation that has become the company’s cash cow.

The third person involved with the Spider-Man origin is Steve Ditko, and unfortunately, the little he has said about the creation of Spider-Man doesn’t help. His earliest mention simply states “Stan Lee thought the name up. I did costume, web gimmick on wrist & spider signal.” (Steve Ditko-A Portrait Of The Master Comic Fan #2 1965) 25 years later, when Ditko finally expanded on his role, he made it clear that he had no knowledge of who did what prior to his getting the script from Stan Lee, and then he offered up a weird scenario where in Stan Lee’s script, there was a teenager with a magic ring, which transformed him into an adult hero, (Robin Snyder’s History of Comics) and it was Ditko who noticed the resemblance to Joe Simon’s, The Fly, and so it was changed into the now familiar spider bite origin.

A small point of interest concerning Ditko’s claim that it was he, who recognized a resemblance between the Stan’s first script, and The Fly. Steve specifically mentioned that he recalled The Fly as a product of Joe Simon, but did not connect Jack Kirby with The Fly, thus failing to also connect Kirby to Spider-Man. Yet nowhere in The Fly is Joe Simon’s name ever credited, but the art is easily identifiable as Jack Kirby’s. It seems very odd that a man who broke into the industry with the Simon and Kirby studio (even inking over Kirby on Capt. 3D) and who had been inking over Jack Kirby the last 2 years, could remember the work of an unlisted editor, but not that of an artist whose work he was most familiar with.

Three stories, with three variations that don’t quite connect. Kirby says it was all his, Lee claims it was all his, and Ditko, he says Stan gave him a script based on a Kirby character, that was then changed. Oh what a tangled web we weave. (sorry, couldn’t resist)

Another point of interest that may account for some of why the story changes, has to do with how the copyright laws changed in 1976. As a result, all the artists working for Marvel in the 1960s were classified as freelancers, and since they were freelancers, they could possibly make future claims for termination of copyrights for any characters they created. (this is the same law that has allowed the Siegel family to claim partial rights to Superman, and Joe Simon to make a claim for Captain America) One way the companies might protect their claim is by showing that the characters and concepts were created by employees, and supplied to the artists. Since Stan Lee was technically the only employee of the three men involved, suddenly all characters in Marveldom were “his” sole creation, and the artists merely illustrated his tales.

But Spider-Man provided a unique problem, because Stan, in a speech at Vanderbilt College in 1972, related how Kirby had first provided a proposal for Spider-Man. Stan stated that after he looked it over, he had a different idea for the “look” of Spidey, and decided that he would offer it to Steve Ditko to draw. He didn’t mention any problem with Kirby’s concepts and plot. It is in later tellings – post copyright law change- that he would stress that Kirby’s proposal, though rejected, were still based his (Stan’s) original ideas.

Which brings us to the heart of the debate: Just what did Kirby propose, what was used or rejected, and where did these ideas come from. That first proposal has never surfaced, though Jim Shooter has mentioned seeing it at Marvel in the late ’70s. So what we are left with is the personal recollections of two men whose memories are hopeless, one of whom is now dead, and a third who won’t talk. The problem here is not that we don’t have eyewitness testimony, it’s that we have conflicting eyewitness testimony. The people involved disagree.

If we can’t rely on first-person testimony, what can we do? I think The Confessor, in Kurt Busiek’s Astro City said it best, “Look at the facts, look at the patterns, and look for what doesn’t fit. Base your deductions on that.”

Criminal detectives have other words for this: evidence, and modus operandi. We can do what historians, detectives, and scientists have always done: ignore the hearsay, mythology, and personal claims and look at the actual physical evidence, in this case, the original comic books, and contemporaneous documentary evidence from unbiased sources. Human behavior is repetitive, we all have our m.o, — our method of operation. It is this human trait that detectives use to narrow down the lists of suspects in any mystery.

It has been said, “an artist is someone who pounds the same nail over and over again.” All artists, graphic or literary, have patterns. They repeat aspects, concepts, a style of punctuation, a brush stroke, lines of musculature, anything that separates their style from the hundreds of others. When trying to identify an unknown artist, one can compare the piece in question with other contemporaneous works to match up these patterns. This method has been used to research everything from Shakespeare’s writings to the works of the Great Masters.

Can this be used on comic books? Yes, it can, and has. Martin O’Hearn is a noted comics historian who specializes in the identification of uncredited comic writers. He matches up subject, syntax, punctuation, themes and other identifiable patterns, and has had remarkable success in matching writers to their non-credited stories.

Likewise, Dr. Michael Vassallo, in his never-ending quest to index all Atlas/Timely Publications, spends endless hours comparing drawing and inking styles to identify unaccredited works of comic art. His goal of identifying the unlisted inker on Fantastic Four #1 & 2 has led him to amass a veritable mountain of inking examples to compare to the actual comic art. What he doesn’t do is blindly accept personal recollections or corporate identifications at face value. If he did, Dick Ayers or Artie Simek would be incorrectly credited with this work.

So this is how I approached the Spider-Man quandary. Rather than focusing on unprovable statements — by men with obvious agendas — made long after the creation of Spider-Man, I would examine their actual concurrent works to see if I could find a pattern of creation that matched up with the concepts, characters, and plot elements found in Amazing Fantasy #15, plus any physical evidence, and testimony from witnesses independent of the three men.

The eyewitness accounts are important, but only if it can be corroborated by the evidence, so where I do refer to a specific quote from Jack, Stan or Steve, it is not as a statement of fact, but rather as a clue that might lead me to some tangible bit of evidence that might lend credence to a claim.

I guess here is as good a time to explain the parameters of my debate. This debate is about which of the three men was most responsible for supplying the character, concepts and the plotting, for the creation known as Spider-Man, as presented in Amazing Fantasy #15. All credits for comic book creation derive solely from the first appearance of the character. Events and graphics in issues 2, 3, or 4 on may be important in the evolution of the character, but they have no bearing on creative rights. We are not debating who in history was the first to come up with a concept such as wall crawling, what we are talking about is who most likely supplied that concept for the title Spider-Man. And we are not debating who fleshed out the characters in later issues; we all acknowledge that Lee and Ditko went on to make Spider-Man uniquely identifiable. We also are not debating who drew the first issue, this was Steve Ditko, and that credit is not in doubt. The debate is who supplied the initial concepts to Marvel for the title and character that became known as Spider-Man.

After tracking down as many Kirby, Ditko, and Lee stories from the previous five years (I didn’t want to go too far back; if there was a pattern, it should manifest itself within a short period), I then broke down the characters and plot elements, to see if there were any that matched up with Spider-Man’s origin.

These are my findings. In all instances, as to the character and plotting, I was quickly able to find amazing similarities with the work of only one of the three men, Jack Kirby. And in the case of the character, not only did I find amazing pattern matches, I also found what I believe was a written template for Spider-Man that predates Amazing Fantasy #15, and leads directly to Jack Kirby. My research also has led me to come to the conclusion that Kirby’s connection to Spider-Man extended beyond that first issue.

THE CHARACTER

The basic concept of Spider-Man is simple, a hero, with the inherent physical powers of a spider- he can crawl up walls, and across ceilings, he has the proportional strength and agility of an arachnid. He has an extra sense that warns him of danger. He manufactures a web shooter that can be used for catching prey, and used as a means of mobility.

I could find no earlier character from either Lee or Ditko that had any resemblance to Spider-Man, none.

As to Jack Kirby, it didn’t take long to track down a pattern match for the physical aspects of Spider-Man, the surprising factor is just how similar the two characters are.

The very last costumed super-hero book that Kirby produced, prior to Marvel, featured an insect hero able to climb walls and ceilings; had super strength, the agility of a bug, and, amazingly, an extra sense that warned him of danger. In The Adventures of the Fly, (Archie Publications 1959,) Simon and Kirby introduced The Fly, a hero with the exact same insect derived powers that show up in Spidey. In fact, the only physical difference is that the Fly can fly. The most interesting aspect for me is the match-up of a “sixth sense” to warn of danger. While the other powers (wall climbing, etc.) might be considered generic to any insect, this warning sense is, as far as I know, something totally unique and beyond the norm of the natural attributes of insects. The addition of this unnatural extra sense showing up in both creations is just too coincidental.

It’s been said that the Devil’s in the details, and it’s these repeated small details that in my opinion, make the strongest case for Kirby being the concept man.

Does the physical similarity between The Fly and Spider-Man correspond and bolster any specific claims made by the three men?

Jack Kirby, in the interview published in Spirit Magazine #39 states that the basis for Spider-Man started with a character called the Silver Spider, an idea first suggested for Simon and Kirby’s own publishing house Mainline.

Yet Mainline never published a title called the Silver Spider, and Kirby stating this doesn’t make it true. Thanks to Greg Theakston’s tenacious research, and the publication of Pure Images#1, (Pure Imagination 1990) we finally got a chance to see and compare the original 1954 proposal of Joe Simon’s Silver Spider. The interesting thing about Silver Spider is that except for the name Spider in the title, there is absolutely no resemblance between Silver Spider, and Spider-Man. The Silver Spider does not have the inherent powers of a spider- he does not climb walls and ceilings, nor does he have an extra sense that can warn him of danger. (at least not in the original Oleck script, and drawn proposal by C.C. Beck) He did not have a web of any sort.

So at first glance, despite Kirby’s claim, there would seem to be no conceptual connection between the Silver Spider, and Spider-Man.

It was Joe Simon who provided the linkage between his Silver Spider, the Fly, and Spider-Man, and just what role Jack Kirby played.

When Archie Publications asked Joe Simon to produce some books for them in 1959, Joe called in Jack Kirby to help out. Joe suggested that they rework his earlier Silver Spider proposal into a character called The Fly. He handed over a file containing the initial Silver Spider proposal to Jack. The file also contained a rejected working logo, and an editorial memo, by Harvey Publications, rejecting the initial proposal — a memo that would inspire Kirby, and would play a compelling role, when later, Stan Lee would ask Jack for a new character; more on this memo shortly.

According to Joe, in The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood Publications, 1990) when Kirby asked him about specific powers for The Fly, Joe told him “Hey, let him walk up buildings, and let him fly if he wants to, It’s a free country. Take it home and pencil it in your immortal style.” Kirby did just this, and the result was The Fly.

Again, Joe saying The Fly evolved out of the Silver Spider proposal doesn’t make it true. It is when we compare the two stories that we see that the Fly’s origin gimmick is consistent with the Silver Spider’s. In both stories, the young protagonist (both named Tommy Troy) is a beleaguered orphan who gains his powers via a mystical ring that transforms him into an adult super hero. Yet the super hero character is different. Where the Silver Spider has no apparent powers except enhanced strength, and a great leaping ability, The Fly has been granted very specific powers; inherent insect abilities, (wall clinging, exceptional agility, a sixth sense and a stinger gun- none of which was in the initial Silver Spider proposal. It is this character evolution, supplied by Jack Kirby, that is the borrowed ingredient that later show up in Spider-Man.

So there is a pattern match that is consistent with Spider-Man and Kirby’s The Fly, and a paper trail that lends credence to Jack Kirby’s claims concerning the Silver Spider connection.

As an aside, Simon had rejected a working title “Spiderman” for his Silver Spider project, and showed a logo to Kirby, leaving little doubt as to which of the three people involved with Spider-Man would have been the one to supply that name

Yet nowhere in either the Fly, or the Silver Spider work up can be found a template for the concept of a web being used as a means of mobility, or as a way of capturing prey. Which brings me to a part of this history that has been overlooked, and in this area lies what I believe to be the only existing contemporaneous written evidence that shows undeniably where the concepts came from, and who brought the basic concept of Spider-Man to Marvel. This is what I consider to be the smoking gun, much like catching the crooks with the blueprint to the bank, and the vault combination.

After Joe Simon submitted his proposal for the Silver Spider to Harvey Publications for acceptance, Leon Harvey handed it over to a young editor by the name of Sid Jacobson for critiquing and approval. In two memos from 1954, addressed to Leon, Sid made it apparent that he was not happy with the proposal. “Strictly old hat” he says, stating that the concept is too generic, with nothing special to set it apart. In the second memo, Sid Jacobson takes the extra step of suggesting just what changes could be done to make this concept more interesting. These memos were in Joe Simon’s, Silver Spider file, they were unearthed, and originally published in Greg Theakston’s Pure Images #1 (Pure Imagination,1990) Here is the pertinent section of memorandum #2.

EDITORIAL MEMORANDUM #2

TO: LEON HARVEY February 23, 1954

FROM: SID JACOBSON

RE: SILVER SPIDER

Conclusions on character:

Physical appearance- The Silver Spider should be thought of as a human spider. All conclusions on his appearance should stem from the attributes of the spider. My first thought of the appearance of a human spider is a tall thin wiry person with long legs and arms. He should have a long bony face, being more sinister then handsome. The face of the Submariner comes to mind.

Powers: The powers of the human spider should pretty much correspond to the power of a spider. He therefore wouldn’t have the power of flight (author’s note: something hinted at in Simon’s proposal) but could accomplish great acrobatical tricks, an almost flight, by use of silken ropes that would enable him to swing ala Tarzan, or a Batman. The silken threads that the spider would use might come from a special liquid, from some part of his costume that would become silken threads in much the same way as the spider insect. These threads would also be used in making of a web, which could also be used as a net. The human spider might also have a “poison” to be used as a paralyzing agent.

Nemesis—His main nemesis should be a natural enemy of a spider—either The Fly, or Mr. D.D.T……

-end of memo-

There is no ambiguity, vagueness, or doubt; Sid Jacobson suggested that for the Silver Spider to work, it would have to become what we recognize as Spider-Man!

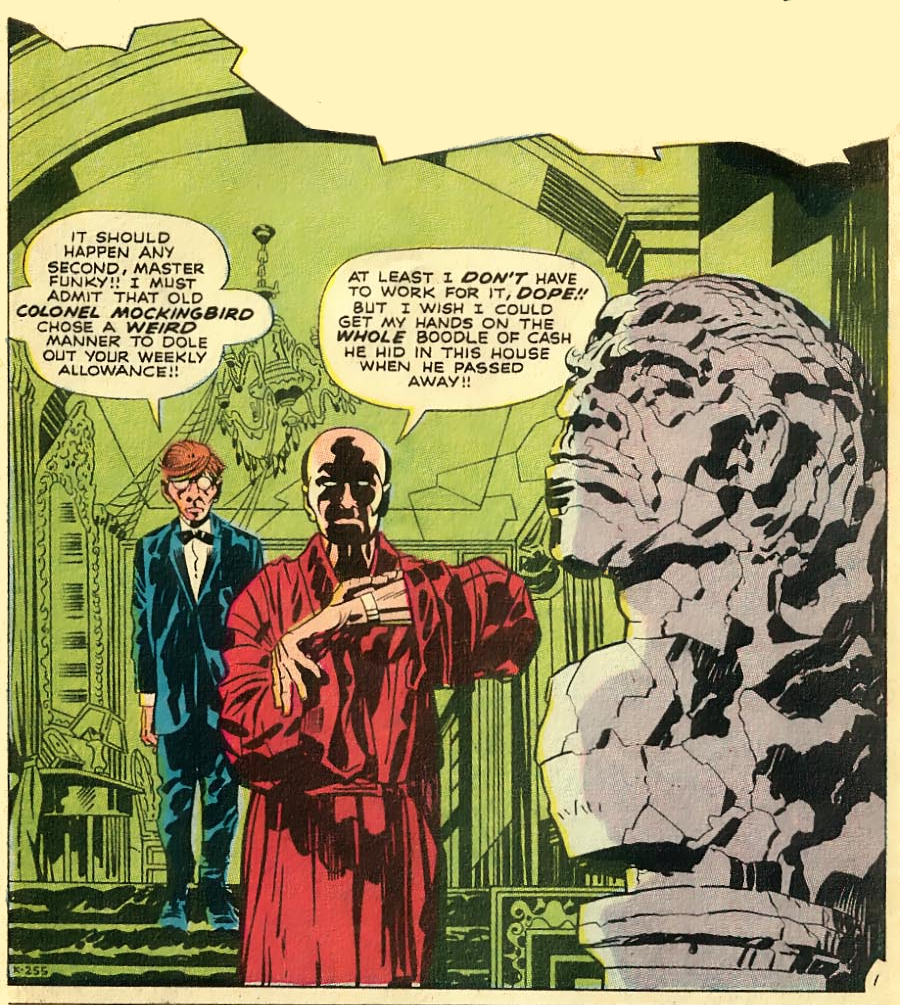

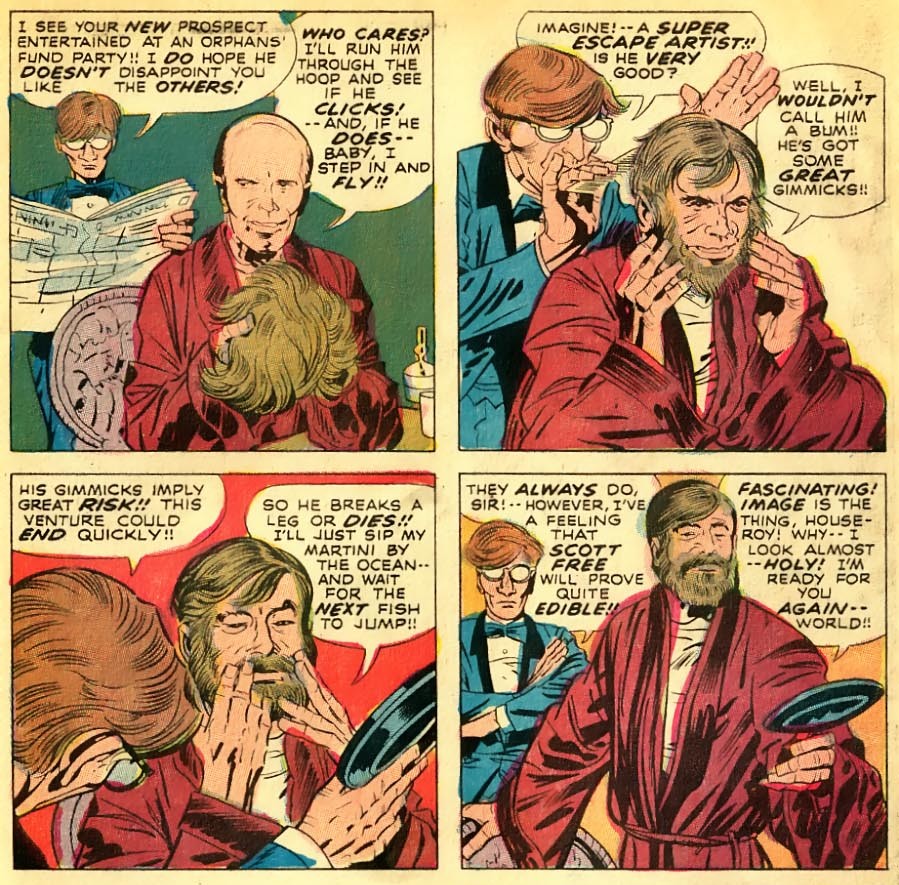

It appears as if Jack took some of Jacobson’s suggestion to heart when he cobbled together the character of The Fly, for he added the detail of inherent insect attributes, but his first specific use of the Spider motif shows up with the creation of The Fly’s arch nemesis. In an interesting reversal of Jacobson’s suggestion of “natural enemies”, Spider Spry, from Adventures Of The Fly #1 would have those long bony arms and legs, though Kirby gave him a bulbous head and torso. (more spider like) He easily walked up thin silken lines, and traps the Fly in a web-like net, and wears a colorful costume complete with a spider icon. More on this character later

Move forward three years, when Goodman decided to go the super-hero route; Kirby is asked to come up with another character, and now the parallels between the Spider-Man creation and the Jacobson memo become undeniable.

Spider-Man would have the natural instincts and powers of a spider; he could walk up walls, and ceilings. He would have the proportional strength, and agility of an arachnid. And more importantly, he could emit a silken thread that he could walk across, or use as a swing. His webbing, a synthesized liquid, which emanated from his costume, was also adaptable as a net in which to ensnare villains, all of this totally identical with the Jacobson memo.

The addition of the extra sense that warns of impending danger, first seen in the Fly, seems to have been an original Kirby item, since it was not present in either the Silver Spider proposal, or mentioned in the Jacobson memo

Evidence, and m.o.; a series of continuing pattern matches, plus a paper trail that leads directly to only Jack Kirby. What are the odds that Stan Lee, working alone, or in collaboration with Ditko, would come up with exactly the same title, the same set of powers and the same weapon?

Some may imply that if all Kirby did was rework a Simon project, shouldn’t Simon get the credit? To some extent I agree, but as I have shown, every facet of Spider-Man’s character, that matches up with The Fly, is an element that Kirby worked on or added to the Fly–nothing was taken from the Silver Spider except the original title, and that had been rejected by Simon. Simon, on his own, had never used the logo, or acted on Jacobson’s suggestions. Simon and Kirby was a partnership, when they broke up, all unused concepts were free game. But in any history of Spider-Man’s creation, in my opinion, both Joe Simon and Sid Jacobson certainly deserve a large footnote.

Try as I might, I couldn’t find any prior Lee or Ditko tales that might have been a template for the character of Spider-Man. None. Lee’s oft quoted statement that he had a long fascination with the pulp hero The Spider, may be true, but there are absolutely no resemblance in either origin, weapons, or powers between the two characters.

Ditko, for his part has acknowledged that the original concept was similar to The Fly, yet he says it was rejected, and changed because it was too identical to the Fly. So I tried to see where they might have changed the character. Try as I might, I could find nothing significantly different between the Fly and Spider-Man. Every unique power that Spidey possesses first shows up in the Fly. Why, if they recognized the similarity between the Fly and Spider-Man, didn’t Stan and Steve make some changes?

There are some specific detail differences, however, in these similar powers: The Fly’s super strength is never explained, it’s just a given. Spider-Man’s is specifically described as the “proportional strength” of a spider — a rather unique concept, (and surprisingly never used by any other insect inspired hero, i.e. Blue Beetle, Green Hornet, Tarantula ) and specific enough for me to try to track down to see if this might be an addition attributable to Lee or Ditko. But again, the only example I could find of any one of these three men giving a character the proportional strength of a bug prior to the creation of Spider-Man is found in a Kirby story. In Black Cat Mystic #60 (Harvey Publications, 1957), in a story entitled “The Ant Extract,” a meek scientist discovers a serum that gives him the proportional strength of an ant. Because of his new power, the scientist is feared and ostracized by authorities. (sounds vaguely familiar) Another small, but novel detail, that shows the evolution of the concept, and is traceable to Jack Kirby.

The mechanical weapon as first created by Kirby has been described by Steve Ditko as a web-shooting gun, and later modified by Ditko into a wrist-mounted web shooter. Again, not taking this quote as fact, my research found that the only pattern match to a costume emanated webbing, is found in the Jacobson memo that Kirby had.

There is another questionable aspect to Steve’s memory concerning the “web gun”. In Steve’s article “An Insider’s Part of Comic History” from Robin Snyder’s History of Comics (Vol. 1 #5 1990) he states, “ Kirby’s Spider-Man had a web gun, never seen in use.” Steve then goes on to describe what he remembers of the 5 page Kirby proposal. He says that the splash page was a “typical Kirby hero/action shot”, and the other four pages are an intro, involving a teenager and a mysterious scientist neighbor. Nowhere in the five pages are Spidey’s, powers and weapons ever shown or described, in fact, according to Ditko, there was no transformation into the hero at all. If this is true, then how does Steve know that he had a “web gun”, by his own words it was never shown or used?

Perhaps Kirby provided some design sketches or spot illos, but that would be in dispute with Ditko’s previous statement that the 5 pages were all he received of Kirby’s, Spidey proposal. Either way, the wrist shooter is a wonderful modification and a stroke of genius, but it is still just a modification–the actual idea of a mechanical web shooter, even by Ditko’s account, was Kirby’s.

In review: every unique physical aspect of the character we know as Spider-Man can be traced back to only one of the three men involved, Jack Kirby. Not only amazingly exact pattern matches, but also a written blueprint that only Kirby had seen. Evidence, and modus operandi. If the concept of Spider-Man was all that Kirby supplied, he deserves co-creator credits, but it doesn’t end there.

The next character is Peter Parker, and while he is Spider-Man, the role of the alter-ego is to present a sometimes opposing character to the heroes. It is this dichotomy that helps create tension and oftimes humor. It is this aspect that keeps the hero and the story grounded in some semblance of reality.

Peter’s character is portrayed as a nerdy, wallflower science whiz. Taunted by his peers for his lack of athletic prowess and social skills. He is rejected by the opposite sex.

Again after comparing the recent works of the three men, I was able to find a pattern match with only one of them, Jack Kirby.

In the late ’50s, Kirby was looking for work, his comic book work had dwindled and he thought of getting into the syndicated strips. One of the strips he proposed was titled CHIP HARDY. Chip was a college freshman on a science scholarship. A regular ‘boy wonder’ taunted the other kids. Moose Mulligan, the campus jock, teased young Chip about why he didn’t try out for football, instead of “hiding behind a mess of test tubes”. Other students followed suit and mocked the youngster, labeling all science majors as “squares”. Eventually, this taunting escalated into a physical confrontation between Moose and Hardy, with young Chip getting the better of it, mimicking exactly the character template and early relationship between Peter Parker, Flash Thompson, and the other school mates. While this strip was never published, Greg Theakston has published a few panels in the back of The Complete Sky Masters of the Space Force. (Pure Imagination, 2000)

Another amazing pattern match is to be found in Tales To Astonish #22, (Marvel Pub. Aug. 1961) in a tale titled “I Dared to Battle the Crawling Monster”, one of the many Kirby/Ayers monster stories, possibly dialogued by Larry Lieber. (unsigned by Lee)

The hero is a high school student, a dorky, bookwormish sort, laughed at by the jocks for his lack of athletic ability, and taunted by the girls. Typically, by the end of the story, it is the bookworm, not the jock who saves the world. Even the visuals of the lead character strongly resemble the Peter Parker character as shown in AF#15.

As to Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, I could not find any earlier templates for the harassed, teen-age, academic style hero. None, and this, frankly surprised me.

There is one aspect of Peter Parker that was consistent to Stan Lee, and that is Peter’s personality. Besides being a science geek, (complete with pocket protector) Peter is shown to be somewhat angst-ridden; doubting of his own worth and unable to fit easily into society. His uneasiness with his new- found powers is atypical of Kirby’s heroes. This inner conflict, and sometimes, outer rage is pure Lee, it is this deeper human psychological aspect that Lee imbued into all of Marvel’s heroes. It is the difference between Ben Grimm of the Fantastic Four, and Rocky Davis of the Challengers of the Unknown.

The villain of AF#15 is a colorless petty crook who has assaulted Spider-Man’s guardian-his uncle. His sole purpose is to create the crisis, which forces the hero into action. This match up is also found in the Fly’s origin. The Fly’s first use of his powers is to bring to justice, a petty crook who had assaulted Tommy’s guardian. This was both characters’ sole appearance.

As to the characters, are my findings beyond the norm at Marvel at the time? I don’t think so. That Kirby constantly evolved and morphed characters and concepts is not an astounding statement. His whole history at Marvel is filled with his taking prior concepts and reworking them to meet current needs.

Fantastic Four was just an evolution of Kirby’s team concept first shown in the Challengers of the Unknown, then transformed into a slightly different version for Sky Masters of the Space Force, and further refined in Three Rocketeers.

The Hulk is just another retelling of the radiation mutated beast story, first done by Jack in Blue Bolt in 1940, with the added in element about saving a young kid from a test blast taken directly from a Sky Masters story.

And Thor is nothing more than an updated version of the “god comes to Earth in times of need” theme, first done by Kirby in Hurricane. (Red Raven #1, Timely 1940) Added to a character, and plot gimmick from a recent Kirby drawn story, “The Magic Hammer”. (Tales of the Unexpected#16, DC Pub. Aug. 1957)

That Stan Lee would take these stock Kirby characters and give them distinct personalities, foibles, and conflicts, soap opera style melodramatic continuities, and hip dialogue is also not really in doubt.

That the character of Spider-Man as originally created was a Kirby concept is to me irrefutable, even without the Jacobson memos the patterns are obvious, with the letters it’s undeniable. There is also strong evidence that, the templates for Peter Parker’s maligned science whiz character, and some of the supporting cast was supplied by Jack Kirby.

The coincidences needed for Stan Lee or Steve Ditko to have come up with these exact elements, absent Jack Kirby, are astronomical. If this was all that Kirby provided to Stan Lee, he would deserve credit, but there is more to creating a character: One must also come up with a story line that showcases the new character, and it is here that the coincidences become positively mind boggling.

THE PLOT

The plot of Amazing Fantasy #15 is simple, yet unique: An orphaned teenage boy receives super-powers during a scientific experiment. After gaining his powers, a loved one is killed due to his inaction. This remorse leads him to vow to never let it happen again, thus becoming a hero.

Again, after cross checking stories by these three men, it became obvious that in structure and theme, the basic plot for Spidey’s origin came from one of the three persons involved: Jack Kirby.

The first plot element has to do with an orphaned, older teenager, who gets super powers via a scientific experiment, and this is intriguing. Even though I tried to approach this in an entirely objective manner, I still had some preconceived notions of both Kirby’s and Ditko’s proclivities. Many of these were shattered by my actual findings. One of these was that it was Ditko’s nature to use older troubled teenagers for his heroes, while it was Kirby’s nature to use younger kids.

So strong is Ditko’s aura surrounding Spider-Man that I just assumed that it was a Ditko trait, but I was not able to track down a single use of older orphaned teenagers, troubled or not, by Steve prior to Spidey.

What shocked me was how easy it was to find the template for the orphaned older teenaged hero, and a title that would provide key elements in piecing together the puzzle. Surprisingly, it was in a title by Jack Kirby.

In The Double Life of Private Strong, (Archie Publications 1959) (not coincidentally the companion title to The Fly) the hero, Lancelot Strong, aka The Shield, is an orphaned high school senior, and like Spider-Man, his surrogate parents were gentle, compassionate, and supportive. His powers were the result of a scientific experiment.

Around this same time, Kirby was also working on the proposed newspaper strip, Chip Hardy, with a teen-aged science whiz hero. In fact, from about 1959 on, just about all of Kirby’s youthful heroes would be older teenagers, and most orphaned. Johnny Storm, Rick Jones (both predating Peter Parker) and the X-Men all fit into this mold.

I could find nothing that matched in Ditko’s, or Lee’s, (sans Kirby) recent past.

The next element is very important: After gaining his powers, the hero loses a loved one due to his inaction, thus providing the impetus for becoming a hero. This may be the critical element that separates Spider-Man from almost all other heroes- and it’s right there in The Double Life of Private Strong. While rushing off to test his newfound powers against a rampaging alien monster, The Shield, (Lancelot Strong), in his teen exuberance, ignores and leaves his best friend Spud in harms way. After defeating the brute, the Shield returns to celebrate his triumph only to learn that the monster has killed Spud. The distraught Shield blames himself, and vows that it will never happen again. Similarly, Spider-man, in a moment of conceit and arrogance, ignores a thief, only to learn that that same thief would go on to kill his Uncle, which in turn, spurs him into action. He then vows that it will never happen again

So in one book, done less than three years before Spider-Man, Kirby used most of the critical plot elements that would show up a few years later in Spider-Man. Certainly Spider-Man’s is more melodramatic as one would expect from Stan’s dialogue, but the basic plot mirrors Private Strong. The panels where the boys mourn the loss of their loved ones are almost eerie in their similarities.

So going by pattern matches, it appears we have the hero and villain from the Fly combined with the origin outline of the Shield.

This cross-pollination of a character from one story, and a plot from another is classic Kirby. He had touches of genius, but during the late 1950’s to mid-sixties, his characters and plots were interchangeable. His storytelling was very formulaic. He had archetypal heroes, a small list of stock villains, and, a set selection of plots. He mixed and matched these regardless of genres. His approach to comics was sort of a Chinese take-out menu, one from column A and one from column B. Nothing became more apparent during my research. In legal lingo, Kirby was a chronic repeat offender. Kirby’s touches are repetitive and easily identifiable. This realization led to one of the more unexpected findings. It appears that Kirby did not cross match the Fly and the Shield one time; he did it twice, and both simultaneously. This pattern can also be found on the Mighty Thor

For Spider-Man, Kirby took the basic character traits (insect), and the villain (petty crook) from the Fly, and the origin gimmick (scientific, older teen), and the dramatic ending (mourning a lost friend) from the Shield.

For Thor, Kirby reversed himself, taking the origin element, (finding of a mystical artifact) and ending, (transformation back to hapless human) from the Fly, and the villain (rampaging aliens) from the Shield, plus adding in a hero from an earlier DC fantasy story. (Tales of the Unexpected #16)

Thor, and Spider-Man appeared on the stands simultaneously. Thor had the earlier story number.

Facts, and patterns says the Confessor, plus look for what doesn’t fit.

Stan Lee and Steve Ditko say they rejected the original plot because of its similarity to The Fly, and created their own. The idea that they would reject one Kirby plot and then replace it with another Kirby plot makes no sense, it simply doesn’t fit. These two men had their own influences and patterns, and if they were to sit down and come up with an original origin, it would not have mirrored a recent Kirby plot, especially if they were specifically looking to avoid the appearance of a Kirby plot. It appears that Stan and Steve took Kirby’s plot, added in Peter’s personality, some of the supporting cast, and maybe the details involving the wrestler and show business, but the basic plot was all Kirby.

Is this use of a Kirby plot, in a book not drawn by Kirby, unusual for Marvel at the time? No! Iron Man’s origin, from Tales Of Suspense #39, uses a Kirby plot, first seen in a Green Arrow story from 1959. (“The War That Never Ended”, Adventure Comics 255) In both stories the hero is captured by an oriental army, and because of his specialty in weaponry, is forced to manufacture a weapon. The hero tricks his captors and creates a weapon that backfires on the enemy and foils their plans.) Yet Don Heck provided the artwork for Iron Man’s first adventure.

Similarly, the origin of Dr. Strange is a reworking of the origin of Dr. Droom from Amazing Adventures #1.(Atlas Pub. June 1961). In both stories an American medical doctor goes to Tibet, and after a series of tests, receives mystical powers from an ancient mage.

The idea that Kirby would plot the origin of a new character is the rule at Marvel in the early ’60s. It would actually be an anomaly if Kirby “hadn’t” provided the origin.

Again, I can’t remember another instance where comic historians have denied credit to the person who supplied the origin sequence.

But it doesn’t stop there, for while I was cross-referencing the plots to see if any matched up with AF #15, I noticed another striking coincidence, and this staggered me! Not only does it appear that Kirby provided the plot for AF #15, it appears that he also assisted in plotting some of the following Spidey stories. The second and third Spider-Man stories have plot elements taken directly from the second and third Private Strong stories. That’s correct; the first three Spidey stories mirror the first three Shield stories.

The second Shield story involves the hero tracking down a Communist spy attempting to steal scientific secrets; the villain tries to escape in a submarine that the hero has to put out of action. This is also the plot of the Chameleon story, in Amazing Spider-Man #1

The villain as a master of disguise was used by Jack Kirby in the first, second, or third story of just about every series he did between 1956 and 1963. (I mentioned he was predictable) It is found in his first Green Arrow story, (Green Arrows of the World, Adventure Comics #250, DC Pub.1958) the second Yellow Claw story, (The Mystery of Cabin 361, Yellow Claw #2, Marvel 1958) the third Dr. Droom tale,

(Doctor Droom Meets Zemu, Amazing Adventures #2, Marvel 1961), the second Fantastic Four story, the second Ant-Man story, and the third Thor story, all preceding AS#1. The specific element of a villain impersonating a hero in order to infiltrate, and/or incriminate him in a crime is one that Kirby used often. Prior to Amazing Spider-Man #1, it can be found in Fighting American, (Three Coins in the Pushcart, Fighting American #7, Prize Comics, 1954) Green Arrow, (Adventure Comics #250) and most recently in Fantastic Four #2. This theme would also be used in the test appearance of Captain America in Strange Tales #114.

In the third Shield, and Spider-Man stories, we are introduced to the recurring pain-in-the-ass authority figure/ nemesis – the one who always gets hoisted on his own petard. A Kirby icon, dating back to Captain America. In both stories the adult child of that authority figure gets into a jam and needs the costumed hero to save him or her. In the Shield’s case, it’s the daughter of the general in charge of the base he is assigned to after being drafted. After she gets trapped in a runaway tank, the Shield must save her. In Spider-Man’s story, it’s the son of the editor of the newspaper who hires Peter Parker, and he is trapped in a runaway space capsule that Spider-Man must rescue. Even after saving their offspring, neither of the authoritarian figures considers the hero a particularly positive force, and both think the alter ego character is a bumbling idiot. In between the Shield, and Spider-Man, Kirby also used this gimmick in the Hulk.

What are the odds, if Kirby didn’t assist on the plots, that the first three Spider-Man stories would mirror the first three Shield stories? Wouldn’t one think that Stan Lee, and Steve Ditko would have their own plotting patterns? Astoundingly, the second issue of Amazing Spider-Man continues in this same vein.

The Vulture story from AS#2 is interesting because not only does it have plot elements from an earlier Kirby story, the bad guy is an exact duplicate of the villain from that same Kirby story. In the first Manhunter story, (Adventure Comics #73, DC Pub. 1942) Kirby introduced The Buzzard, who, in an uncanny parallel to the Vulture, is a skinny, stoop shouldered, hump-backed, beak nosed maniac, dressed in a green body suit with a feathered collar that encircles the neck. Both men have the power of flight, the Buzzard by flapping his cape, and the Vulture via mechanical wings, and a magnetic unit.

Both men’s schtick is to openly challenge the authorities and the media by boasting of their evil plans before they commit them. The Buzzard goes so far as to actually kill a reporter to deliver his message; the Vulture (in post code times) simply throws a rock through J. Jonahs’s window.

The Tinkerer story in AS#2, has a very interesting hook, a plot element where a radio is doctored and infiltrated into scientists and government officials’ houses in order to spy and/or control them. This is not some generic scheme, but a very detailed and specific plot element used by Jack Kirby several times. The earliest use is in Captain America #7, (Marvel Pub. Oct.1941) in a story titled “Horror Plays the Scales”. Kirby again used this element in a crime story from Headline Comics#24, (Prize Pub. May 1947) titled “Murder on a Wavelength”.

The alien aspect of this Spidey story appears adapted from a Kirby, Dr. Droom story. In his third story, (Doctor Droom Meets Zemu, Amazing Adventures #3, Marvel 1961) Droom is following a suspicious character and overhears a plan by aliens in which one will infiltrate humanity and lay the groundwork for an alien invasion. Spider-Man’s capture and escape method seem to be lifted from a Challengers of the Unknown story. (The Human Pets, Challengers of the Unknown #3, DC Pub.1958)

I could find no matching plots from Lee or Ditko. All of these stories are structured in typical Kirby style, with little characterization, all out action endings, devoid of any of the subtlety, pathos, or irony usually associated with Lee/Ditko offerings.

And it goes on this way for a few more stories. This similar plotting sequence is a lot like DNA testing, one or two match-ups doesn’t mean a thing, but the odds increase exponentially with each added matched item.

It’s a good time for me to mention something I call “Kirby’s silly science.” As identifiable as fingerprints, we all recognize it: scientific plot elements so ridiculous in their implausibility, yet so exciting visually, and conceptually, that it’s immediately acceptable. Mr. Fantastic, reaching up and catching a nuclear tipped Hunter missile in full flight, and throwing it miles away into the bay. The Submariner; in the freezing void of space, leapfrogging, from meteorite to meteorite, only to land on Dr. Doom’s spaceship, unstable molecules, and such.

The early Spider-Man stories were full of this pseudo-scientific stuff. In the story involving J. Jonah Jameson’s son trapped in the space capsule, we first see NASA trying to snare the disabled capsule in a net suspended from a parachute, when this fails, Spider-Man, straddling a jet, snares the space capsule with his web and rides it like a bucking bronco, completely overlooking the fact that space capsules orbit far above the range of a jet, and the extreme heat generated during re-entry would fry a human being, even one with Spider powers.

This feels like Kirby’s silly science to me; in fact, it is reminiscent of a scene in Sky Masters where they try to rescue an errant space capsule with a hook attached to a jet, combined with a satellite repair story, also found in Sky Masters.

Another facet of Kirby’s silly science, and plotting pattern, is the anti-climactic ending, where the scientist hero, in one panel, whips up some bit of gadgetry that defeats a villain who has been beating his brains out for the previous 15 pages.

Challengers of the Unknown’s Professor Haley was good at these instant cures, and the FF’s Reed Richards was the master, but early on, Peter Parker stood toe to toe with them. In the first Vulture story, from Amazing Spider-Man #2, after getting his hat handed to him, Peter Parker, based on nothing but a hunch, theorizes that the Vulture’s powers must be magnetic and whips up, in one panel, an anti-magnetic device with his handy dandy screwdriver. How Kirbyish can you get? Similar elements occur in the first Doc Ock, (a super acid) and the first Lizard story. (an antidote) This kid was good!

Compare this to the atmospheric, cerebral, and quietly ironic solutions and climaxes that Lee and Ditko specialized in on their sci-fi/horror tales of this period. This deus ex machina style ending is not part of their repertoire, it simply doesn’t fit.

To Kirby, scientists were scientists; he made no real distinction between the disciplines. In one story the hero was a physicist, the next a chemist, perhaps a biologist or a metallurgist, whatever was needed for the story. Hank Pym, aka Ant-Man, was equal part entomologist, chemist, cybernetician, and machinist. Reed Richards was master of all sciences, and Peter Parker, though a high school student, was equally as versatile. After receiving the spider powers, this kid went home and with his Mr. Wizard Home Chemistry Lab created a formula for a web, and the means to propel it. Then in the Vulture story he suddenly becomes a physics master, and invents an anti-magnetic device. In the Tinkerer tale, he is assisting an electronics genius, and up against the Lizard, Peter’s become an expert in serums and antidotes. This boy was truly amazing! It’s a shame he gave all that scientific ability up to become a news photographer. Kirby’s handiwork is all over the early stories.

Thankfully, these pseudo-science elements soon ended, and I’m thinking it happened when Jack stopped assisting Stan on Spider-Man plots, and Ditko took over.

So it seems clear that Kirby’s participation with Spider-Man extended further than just a rejected proposal. It appears that he not only created the character, he also assisted greatly in the origin and early story lines and added many early plot elements.

Again, is this out of character? No. Kirby helped Stan with the plotting of several characters even when not specifically drawing them. The plot to the origin of Iron Man , several of the early Thor stories, and some of the Torch stories from Strange Tales, not drawn by Kirby, have unmistakable Kirby supplied villains, plots, and dramatic elements. Daredevil showed some early Kirby involvement. Why wouldn’t Kirby assist Stan on Spider-Man? The early Marvel titles and characters were never considered private domains. Stan certainly had no compunction about Kirby doing the first 2 covers, or a back up story.

This brings me to a facet of Spider-Man I hadn’t mention before.

THE COSTUME

In all my debates concerning Ditko and Kirby, I had always assumed that when Kirby claimed he designed the costume, he was in error; in fact, this was always a sticking point with me. Recently, though, I have had reasons to wonder about that claim.

This particular debate point does not emanate from Kirby’s period of dissatisfaction with Marvel or Stan Lee. In that speech at Vanderbilt in 1972, Stan relates how during the late ‘60s, when asked, he could never remember who designed Spidey’s costume. He wasn’t sure if it was Jack or Steve. It was common for Kirby to design costumes for other artists’ characters, such as Iron Man for Don Heck. Heck is on record as saying that Kirby also designed many of the villains that appeared in Heck drawn books.

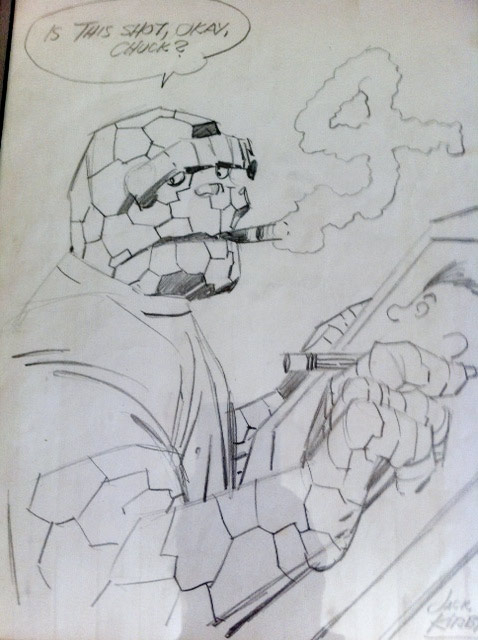

Then, there is this little quote from Foom Magazine #11, 1975. In the middle of an article about Kirby’s return to Marvel after his brief layover at DC, the author states, “It’s not generally known that it was Jack Kirby who designed Spider-Man’s costume.” This isn’t in a fanzine, it’s not a quote from an interview with Kirby, and it’s not in a reference book, it’s right there in an in-house publication of Marvel’s.

As with all quotes, I can’t guarantee it’s accuracy, but it seems that at least at that time (1975) the feeling at Marvel was that Kirby had designed the costume, and as mentioned earlier, Jim Shooter says the Kirby proposal was still around at that time.

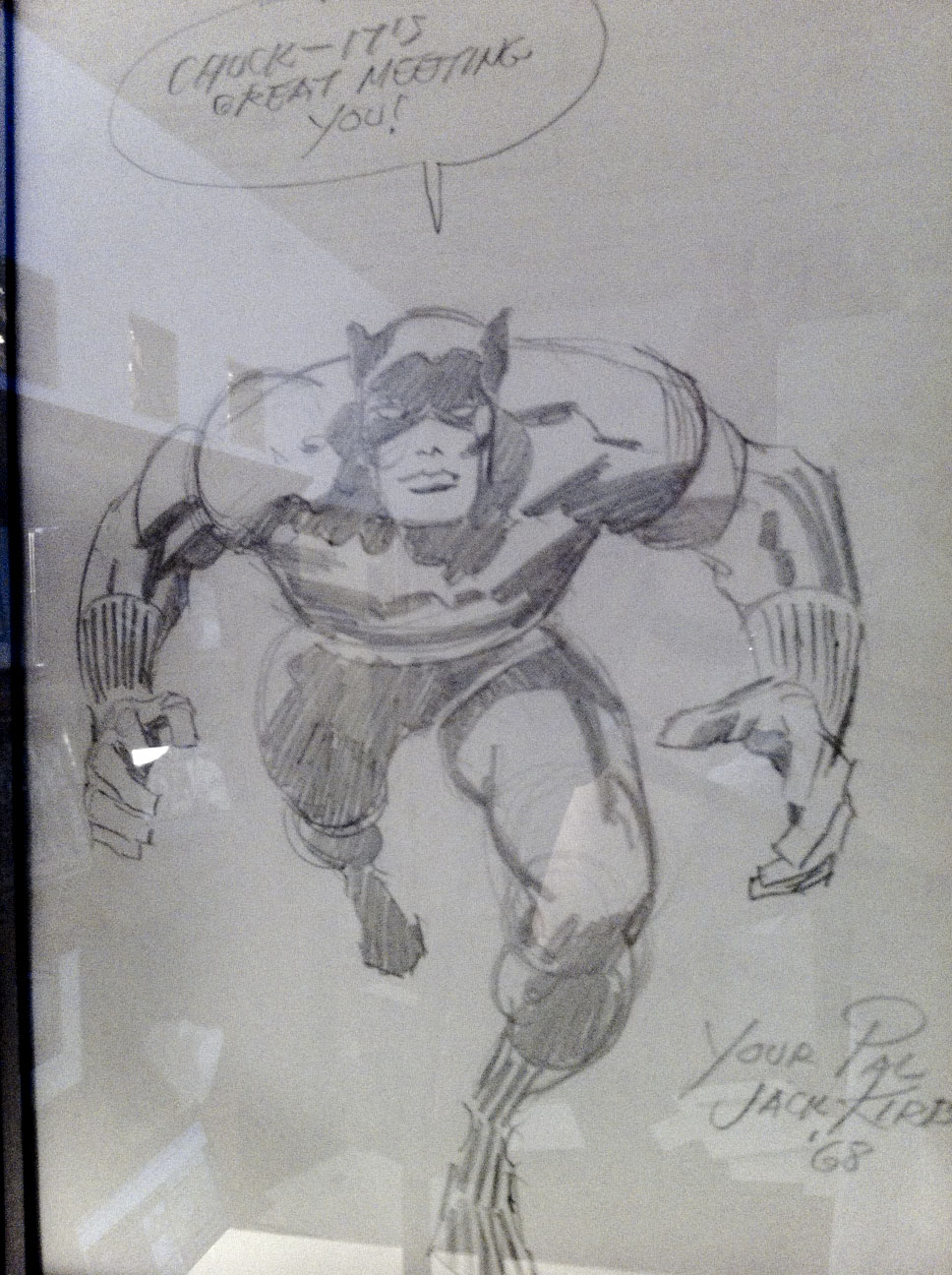

Unlike the match between the Vulture, and the Buzzard, there is no direct similarity between Spider-Man’s costume, and any drawn previously by Ditko or Kirby. Yet there are some design patterns that do match up with earlier design work. If one places a drawing of Fighting American, (a Kirby hero) next to one of Spidey, and erases all of the small decorative details, leaving only the outline of the costume, a curious pattern emerges. Both characters have a dark color top, dissected in the front by a brighter colored midsection that begins narrow at the waist, and expands upward to the shoulders, where it then turns and runs down the arms, slicing the sleeves into two separate sections that ends at the gloves. On the back of the costumes, this two-color pattern continues back up the sleeves, and cuts across the shoulder blades. The facemasks both show a bold design around the eyes that sweep up and back.

Another small but aggravating item: Spider-Man has always been drawn with a strange looking spider icon on his back. Fact is, it doesn’t look like a spider so much as a tick or other small single-bodied insect. The spider drawn on the front of Spidey’s costume is much more accurate, showing a double sectioned body with the legs coming out of the torso section. Why would Ditko use such a different and inaccurate icon for the back of the costume? I can’t answer that question, but the spider on the back of the costume is remarkably similar to the spider icon that appears on the Kirby designed character Spider Spry from the Fly series. (yes, him again) What are the chances that two separate, and unique artists would choose such a similar, yet inaccurate depiction of a spider for a costume decoration?

For those that think I might be purposely ignoring elements that point to Ditko let me say that there ARE several design aspects that shout out Ditko.

First, the circular design with the webs radiating out from the center as seen in Spidey’s mask and the spider signal can be traced back to a cover sidebar used on the Charlton, horror/fantasy titles in 1958. While I have no proof that Ditko designed that sidebar, he certainly would have been familiar with it.

Secondly, and most convincing is something that was pointed out by the ever observant Simon Russell, from the kirby-l e-list. He observed that Steve Ditko rarely ever gave his characters visible belts and trunks, while Kirby always did. Is this born out by comparison? Very definitely!!

Most of Ditko’s early characters especially showed this trait. Captain Atom, Spider-Man, Vulture, Mysterio, and Kraven all have one-piece leggings unbroken by any hint of separate shorts. Kirby, on the other hand almost always gave his characters belts and shorts.

None of this is very convincing, so I looked to see if Kirby’s and Ditko’s words offered a clue, and if their memories stand up to actual research.

In his 1990 article, Steve Ditko says that he gave Spider-Man a full, facemask in order to hide Peter Parker’s boyish face, and to add mystery. This sounds quite logical, and it’s hard to prove or disprove, but, based on comparison, the idea of a full facemask is not in itself an identifiable pattern.

Kirby’s first hero, The Lone Rider, had a full, facemask, as did Manhunter from 1942. Iron Man, Black Panther, and Mister Miracle, etc. would follow. Many of Kirby’s villains had full, facemasks, the Red Skull and Dr. Doom chief among these.

On the other hand, Ditko’s Captain Atom, Dr, Strange, the Blue Beetle, all had half masks, or none at all. In fact, on Ditko’s other young super-heroes like the Hawk and Dove, he does not give them full facemasks, so the idea of a full covering mask is not a telltale pattern with either man.

Also from Ditko’s 1990 article, he states when he was designing the costume, he had to match the costume to the powers. “For example; a clinging power, so he wouldn’t have hard soles or boots…”

In the Pure Images #1 article, he expands “…. and since the character crawled walls, no soles were added to his feet.” Later Greg Theakston adds, “Ditko felt that hard soles on the boots wouldn’t be appropriate to a wall walking hero, and Kirby always draws the hard soles.”

These are interesting looks into how individual artists approach a creation, but in this specific case they are wrong factually, and conceptually.

Just 2 years earlier, Kirby had created a spidery character that was extremely agile, and could easily walk up silken lines. Spider Spry, of Fly fame, had “soft soled” booties that facilitated climbing. Looking at the actual record, it appears that Kirby almost always gave his nimble, agile type characters flexible footwear that would facilitate climbing and gripping. Besides Spider Spry; Toad, Cobra, and the Beast all had either soft soled shoes, or bare feet. Which brings me to my next observation.

Besides being wrong about Kirby’s tendencies, Ditko is wrong even as to his own design choices, for in the first 3 Spider-Man stories, Spidey IS shown with hard soles on his feet, in fact rippled style hard soles similar to those found on the Fly..

It may well be that sometime after the first 3 stories were done, Ditko decided that a crawling hero didn’t need hard soles, and so he changed them, but why claim that it was done specifically to differentiate between his and Kirby’s design choices? Unless the first 3 issues were somewhat based on Kirby’s designs.

So the few details that Ditko has provided don’t really help, in fact, they raise more questions since some are contradicted by actual comparison.

What about Kirby’s recollections?

Kirby has never, in my research, listed any specific details when he talked about “creating” the costume, but, thanks to Mike Gartland, (a frequent Kirby chronicler) I was able to track down an early unwitting mention.

In Excelsior #1, a fanzine from 1968, Kirby is being interviewed.

The writer asks, “Did you draw the Vision? If you did, do you remember the powers that he possessed, and could you tell us of these powers?”

Kirby responds, “I created the Vision as a feature of Marvel (Timely) comics. He was the forerunner of the SPIDER-MAN and Silver Surfer Eye. (Eds. Note: The huge pupil-less eyeballs both heroes possess.) If I remember correctly, his powers were of a mystic nature.”

So once again, we have Kirby, in this case unexpectedly, supplying a small detail concerning Spider-Man that is backed up by comparison, for the Vision, a mysterious hero from another plane did have white blank eyes.

He certainly wasn’t saying that Steve Ditko used the opaque eyes based upon Kirby’s earlier use of them with the Vision. This was in 1968, long before the debates about Spider-Man began. Why would Kirby offer up such an unsolicited tidbit while responding to a question about a totally different character if it wasn’t true?

Ditko, to my knowledge has never mentioned where the idea for the opaque eyes came from.

This Kirby quote; on its own, doesn’t prove anything, but it does add to the strange conflicting nature of the debate.

Lastly, it’s been mentioned that Kirby could never draw the Spider-Man costume correctly, which would be strange if he created it. This sounds plausible, but the fact is that Kirby did not draw Spider-Man all that much, and Kirby could never keep the details of any of his costumes straight. His inkers would spend hours making corrections on the costumes. Kirby was a penciller by nature, and little details such as the curl of a spider web was a detail that wasn’t important in the pencilling stage, it was simply hinted at. He had the same problem with Fighting American’s stripes and wing chest pattern, never getting it the same way twice. Look at the early issues of Thor, and note the costume differences.

By the way, Ditko had the same problem, he could never decide if the webbing detail on the costume curled up, or down. He sometimes had them going both directions on the same drawing, and, check out how different the spider icons on the costume front appear even in the same story.

All of these are fairly circumstantial, and if I was a betting man, I would guess that Spidey’s costume is a hybrid, mostly Ditko, with some Kirby bits taken from Kirby’s original proposal.

CONCLUSIONS

So much for my actual research, now let me speculate a little further. Here is how I think it went down.

In mid-1961, Martin Goodman noticed that the sales of the Atlas monster books were slowing down, and while looking for a replacement genre, he realized that DC seemed to be having some success with super-heroes. He decided that Marvel should take a hesitant step in that direction, and either he or Stan Lee talked to Jack Kirby, who had a 20-year history of creating super-heroes. They decided on a team concept with a twist, the characters would not always get along. Kirby went home and cobbled together a story using parts of his last 2 team series, the Challengers of the Unknown, and his recent syndicated strip Sky Masters of the Space Force, and he presented it to Stan Lee. Stan added in the personalities, the background details, the speech patterns, and Fantastic Four was born.

Seeing that the FF was selling but still a little wary of jumping full bore into the super-hero market, Stan next talked with Jack about using an Atlas-style monster as a hero. So Kirby went home, matched together an Atlas monster with a Sky Masters plot element dealing with a scientist saving a kid from a rocket blast, threw in his radiation-caused mutation concept he had used since Blue Bolt days, and you have the Hulk. Again Stan added in the soap opera, the personalities, the linear continuity, and the human aspects he specialized in.

Martin, seeing that both series were selling, decided to go balls to the wall into the super-hero genre, complete with costumes, secret identities, and all the trappings. Stan again went to Jack and asked him if he had any other concepts lying around. Kirby, doing just as he had with the FF – went back to the last two pure super-hero series he had worked on, took the character aspects from the Fly, plus elements suggested by Jacobson, mixed it in with the plot from the Shield, used the original title from the unused Simon proposal, et voila! Spider-Man!

It is possible, in fact probable, that when Kirby presented this proposal to Lee, Stan had some reservations because his vision of the character was a little different. It didn’t matter because Kirby wasn’t scheduled to draw this feature anyway—Stan, and the new artist could make the changes. They could flesh out, and add their own take on the characters–Kirby was too busy: He was drawing the FF and the Hulk full time, and besides Spider-Man, he had simultaneously worked up Thor. (using the same source material)

All this fits in with the very first account of how Spider-Man came to be. Remember, Stan said that Kirby was too busy and he (Lee) chose Steve Ditko to draw the feature after the concepts were done, and it fits in with Ditko’s first recollections. But does this fit in with what we know about how Marvel worked in the early 1960s?

I think it does. Marvel had a modus operandi also. Evidence shows that Kirby helped out on just about every new project, even the ones he didn’t draw. (origin plot, and costume design for Iron Man, splash page, cover and plot elements for Daredevil, etc.)

Why wouldn’t Jack be involved similarly in any Ditko projects? There were no separate fiefdoms at Marvel at this time. Kirby certainly helped out with the first two covers, he provided an advertising blurb in the first issue, he did a back-up story in #8. Jack did cover retouches and corrections. He also did a Spider-Man crossover story in Fantastic Four Annual #1 in the summer of 1963, and in Strange Tales Annual #2, Fall 1963, both of which appeared before AS#6. The Fantastic Four was intertwined with Spider-Man like no other Marvel series.

In the early days of Marvel, there was no sense of separate books; everyone contributed to every series. It’s amazing, but I don’t think coincidental, that every member of the bullpen was multifaceted: Lee would edit, write, and script; Leiber would pencil, ink, and write; Kirby would pencil, create, and plot; Ditko could pencil, ink, and plot, etc. There seems to have been a true all-for-one atmosphere early on in the bullpen. I actually think this is why these men were the ones picked when Stan Lee regrouped Atlas in 1959. It was this flexibility, and multi-talented nature that allowed Stan to create the Marvel method of storytelling.

So, to wrap up, we have the title of the series, which was likely contributed by Kirby. We have the main character of the series surely created by Kirby, with an assist to Sid Jacobson. And we have the origin, and first couple of stories, most likely plot assisted by Kirby. We may even have the costume based somewhat on a Kirby design. How much more does it take to deserve co-creative status?

Never the less, I am not on any campaign to get Kirby an official credit on Spider-Man. Ditko/Lee works just fine for me. Yet for historical purposes, I do believe that his contributions should be recognized.

So does this mean that Stan Lee, and Steve Ditko are lying? I don’t think so. I think this is an example where each one is telling the truth from their own perspective. Jack Kirby was a conceptualist, an idea man, he felt that creation was the coming up of new ideas. Stan Lee is a writer, he’s a word man, he naturally feels the act of creation starts with the fleshing out of the personality and giving voice to the character. And Steve is an artist, his idea of creation is the giving of form, and texture, and atmosphere to a shapeless thought. To thine own self be true, and I think they are.

In my opinion, Spider-Man is the classic example of a true collaboration, omit any one of the three men involved and you end up with a weaker, or non-existent creation.

If just Kirby and Lee had worked on the title, we would have invariably seen it head into the all-out adventure, or cosmic/mythic realms of Kirby’s other titles, thereby losing out on the gritty, earthiness Ditko added. If Lee and Ditko had created it from scratch, we would have had a hero more like the cerebral Dr. Strange, lacking the action/adventure facet that Kirby added. The combination helped eliminate the individual excesses, while keeping the best of each.

Just because Kirby’s participation ended quickly doesn’t detract from his role in the creation, without his character concepts, and strong action based foundation, Spider-Man might never have found that perfect mix of the psychological and physical aspects. Left to his own devices, Ditko’s characters and stories usually lack the testosterone based fun fantasies, that pure physicality, that the super hero genre demands. His characters thought too much, and acted too little.

And without Stan Lee, in my opinion, we would have been without the single most vital ingredient that made Spider-Man the most unique character in comics. Human frailty!!!

More than any other character he worked on, Stan identified with Peter Parker. His vision of the everyman as hero made Spidey the most conflicted, the most human, and the most unique hero ever created. His blueprint was the perfect recipe for a super hero in the post war era. It was an age when the common man, no longer felt in control of his own destiny. Spider-Man was not just fighting bad guys; he was fighting our doubts, our rages, and our feeling of helplessness. He, like most people, (especially the teens reading his books) was looking for his role in society, and was turned away at every stop. Stan Lee made Spider-Man one of us. This is why Spidey not only continued, he thrived, long after both Kirby and Ditko, no longer had any input.

Together we got the perfect blend of Kirby’s solid histrionics, Ditko’s philosophic atmospherics, and Lee’s melodramatic human voice.

It just don’t get any better folks.

Who created Spider-Man? There’s room for all three.

Stan Taylor

This article was very time and labor intensive, and I need to thank some people. First and foremost, Pat Hilger and M.I. for their unselfish access to their books. Greg Theakston for leading the way. Blake Bell for inspiring me and keeping me jazzed. And the Kirby-l and Ditko-l for their prodding and doubting natures.

— Stan Taylor