Previous – 2. A World Divided | Contents | Next – 4. 1940, The Year Of Living Furiously

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

ESCAPE TO NEW YORK

Half a world away a low, mean rumble was forming, it came in the roar of fires, the flash of long knives, and the click-clacking of hobnailed boots. The Old Country was once again threatening to intrude on the lives of those who had escaped. In Germany, an expatriated Austrian was raising the specter of Jewish oppression in order to gain political power. Almost immediately upon assuming the Chancellorship of Germany, Hitler began pushing legal actions against Germany’s Jews. In 1933, he proclaimed a one-day boycott against Jewish shops, a law was passed against kosher butchering and Jewish children began experiencing restrictions in public schools. By 1935, the Nuremberg Laws deprived Jews of German citizenship. By 1936, Jews were prohibited from participation in parliamentary elections and signs reading “Jews Not Welcome” appeared in many German cities. (Incidentally, these signs were taken down in the late summer in preparation for the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin). These actions did not go unnoticed.

1933 was a momentous year. It started early when Adolf Hitler became a coalition chancellor of a bitterly divided Germany. FDR was inaugurated as the 32nd president and instituted what became known as the New Deal. Prohibition was appealed. The Dust Bowl swirled. Urban legend says an unemployed Jewish novelty salesman named Max Gaines was cleaning out the attic at his mother’s house. To kill some time, he began reading some Sunday funnies from a collection his father had saved. Suddenly the idea hit him: if he enjoyed reading old comic strips like “Joe Palooka,” and “Mutt and Jeff,” maybe the rest of America would, too!

The truth is somewhat drier and mundane. In 1929, a pulp publisher Dell Publications attempted a weekly tabloid style publication in full color featuring new stories. The cover was soft and pulpy. This was a very early attempt at a newspaper type insert yet sold at newsstands, and died after only 13 issues. Created by George Delacourt in 1921, Dell Publication majored in pulps, but experimented greatly with different formats and themes. These color inserts; remembered only by the company that printed them; Eastern Color Printing Company of Westbury Connecticut were the first market available comic pamphlet ever published. Eastern continued printing odd tabloid, newspaper comic inserts, and broadsized advertizing publications when an employee—probably Harry Wildenberg and or M.C. Gaines–suggested that folding the tabloid size sheets in quarters would economically make for a small book sized pamphlet. The problem of sequencing the individual pages printed 4 at a time on newspaper sized sheets into an orderly stack was solved by Morris Margolis of the competing Charlton Company, who had been hired to do the binding. Charlton was a nearby firm in Derby Connecticut that had started out as a cereal box printing company that also published multiple style publications such as racing forms and music lyric mags.

Eastern was a printer, they had no experience as a publisher, so they approached Dell-the earlier comic publisher to front the new project. A 50/50 split was worked out for Dell to publish.

Source material was worked out through the reprint of syndicate suppliers for 10 dollars a page and customers were found through regular advertisers of Eastern like Milk-O-Malt, Kinney Shoes, P&G and Wheateena. They produced the first modern sized comic.

Their first book was Funnies On Parade (1934) a Procter and Gamble giveaway. The initial run was 10,000 issues which disappeared quickly as kids redeemed the coupons in record time. Gaines quickly worked on other companies to join in. His next was A Carnival Of Comics, marketed as a department store premium. This book had an amazing 100,000 printing of which Gaines saved a few dozen for his own. Gaines hit on the idea of pasting a ten cent price on leftovers of A Carnival of Comics, and as an experiment dropped the remaindered copies at several different newsstands. The test case was a greater success than he had expected; within the weekend they had all sold out. Comic books were on their way as a new force of generating income for publishers. With the success of A Carnival of Comics, Max Gaines followed through with another comic-book title, a one-hundred page comic book called Century of Comics. Between 100,000 and 250,000 copies of both Century of Comics and A Carnival of Comics would be given away as a premium that year of comics’ infancy.

Dell did some research and the results weren’t especially favorable; with complaints about the quality and worries about the attraction of reprints soon fizzling out. Dell to their sad regret backed out of the deal. Eastern decided to self-publish and found a backer when supply leader American News became the newsstand distributor.

Eastern followed in May with Famous Funnies #1, Series 2, the first monthly comic book to be sold on newsstands. The first issue relied upon material borrowed from the earlier books, but by the second issue, they began buying new material at 5 dollars a page. A new dynamic had entered the industry.

After small start-up losses, issue #8 turned a profit (earning $2,664.25), and an industry was born. Like Johnny Appleseed, Gaines took his idea to other pulp, and magazine publishers and new comics sprung up over night. In 1935, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson-as officious as his name- began printing all-new material and named his book New Fun. By 1941 thirty comic-book publishers were producing 150 different titles monthly, with combined sales of 15 million copies and a youth readership of 60 million, making the emerging comic-book industry one of the few commercial bright spots of the Great Depression.

1934 brought the first big change to the Lower East Side. Franklin Roosevelt had released government funding for individuals who wanted to rebuild the cities. The first money went to a river edge section of the Lower East Side sarcastically called “Lung Block” owned by flamboyant developer Frederick French; also the builder of Tudor City. This area had been given that tag due to it having the highest percentage of tuberculosis sufferers in the U.S. This was the worst of the worst, a section so bad that the neighbors shunned it. Its mix of seafaring transients, lowlifes, disease, prostitution and beer joints set it apart from the residential neighborhoods on all sides.

Isaac N. Phelps-Stokes, the noted reformer wrote;

“The Lung Block, as I named it then, was far down on the East Side near the river. In early years, when that quarter was a center of fashion in our town, many of the buildings had been great handsome private homes, but long ago they had been turned into grimy rookeries, the spacious rooms divided into little cell-like chambers, many only stifling closets with no outer light or air. I can still smell the odors there. In what had been large yards behind, cheap rear tenements had been built, leaving between front and rear buildings only deep dank filthy courts. Nearly four thousand people lived on the block and, in rooms, halls, on stairways, in courts and out on fire escapes, were scattered some four hundred babies. Homes and people, good and bad, had only thin partitions between them. A thousand families struggled on, while many sank and polluted the others. The Lung Block had eight thriving barrooms and five houses of ill fame. And with drunkenness, foul air, darkness and filth to feed upon, the living germs of the Great White Plague [tuberculosis], coughed up and spat on floors and walls, had done a thriving business for years.”

KVNY

Lillian D. Wald recalls a visit to Lung Block that catalyzed her desire to remain and help this part of the city;

“From the schoolroom where I had been giving a lesson in bed-making, a little girl led me one drizzling March morning. She had told me of her sick mother, and gathering from her incoherent account that a child had been born, I caught up the paraphernalia of the bed-making lesson and carried it with me.

The child led me over broken roadways, — there was no asphalt, although its use was well established in other parts of the city — over dirty mattresses and heaps of refuse — it was before Colonel Waring had shown the possibility of clean streets even in that quarter — between tall, reeking houses whose laden fire- escapes, useless for their appointed purpose, bulged with household goods of every description. The rain added to the dismal appearance of the streets and to the discomfort of the crowds which thronged them, intensifying the odors which assailed me from every side. Through Hester and Division streets we went to the end of Ludlow; past odorous fish-stands, for the streets were a market-place, unregulated, unsupervised, unclean; past evil smelling, uncovered garbage cans; and — perhaps worst of all, where so many little children played — past the trucks brought down from more fastidious quarters and stalled on these already overcrowded streets, lending themselves inevitably to many forms of indecency.

The child led me on through a tenement hallway, across a court where open and un- screened closets were promiscuously used by men and women, up into a rear tenement, by slimy steps whose accumulated dirt was augmented that day by the mud of the streets, and finally into the sickroom.

All the maladjustments of our social and economic relations seemed epitomized in this brief journey and what was found at the end of it. The family to which the child led me was neither criminal nor vicious. Although the husband was a cripple, although the family of seven shared their two rooms with boarders, — who were literally boarders, since a piece of timber was placed over the floor for them to sleep on, — and although the sick woman lay on a wretched, unclean bed, soiled with a hemorrhage two days old, they were not degraded human beings, judged by any measure of moral values.

In fact, it was very plain that they were sensitive to their condition, and when, at the end of my ministrations, they kissed my hands (those who have undergone similar experiences will, 1 am sure, understand), it would have been some solace if by any conviction of the moral unworthiness of the family I could have defended myself as a part of a society which permitted such conditions to exist. Indeed, my subsequent acquaintance with them revealed the fact that, miserable as their state was, they were not without ideals for the family life, and for society, of which they were so unloved and unlovely a part.”

That morning’s experience was a baptism of fire. Deserted were the laboratory and the academic work of the college. I never returned to them. On my way from the sick- room to my comfortable student quarters my mind was intent on my own responsibility. To my inexperience it seemed certain that conditions such as these were allowed because people did not know, and for me there was a challenge to know and to tell. When early morning found me still awake, my naive con- viction remained that, if people knew things, — and “things” meant everything implied in the condition of this family — such horrors would cease to exist, and I rejoiced that I had had a training in the care of the sick that in itself would give me an organic relationship to the neighborhood in which this awakening had come.”

-end-

Lung Block section was to be torn down and rebuilt as a 4 block higher quality low income housing development; replacing the older tenements. The new development was to be called Knickerbocker Village. The out with the old, in with the new atmosphere wasn’t universally loved. Long time residents knew that thousands of existing homes would be torn down to make way for newer homes, without any promise for the displaced being returned. Some were even nostalgic for the old times, romantically remembering the closeness, and uniqueness of the neighborhood—much like old soldiers telling happy stories of their exploits while conveniently leaving out the dead who never returned.

The red bare brick 12 story buildings loomed over the 5-7 story tenements

Jimmy Durante, the entertainer, who grew up in the Lung Block ward, reminisced to Joseph Mitchell about a time “‘when the East Side amounted to something’….Sitting there in the dark theater, nursing his hangover, the big-nosed comedian began to talk about his childhood, the days when he used to run wild on Catherine Street, raising hell with the other kids, the days when he liked to go barefooted and they had to run him down and catch him every winter to put shoes on him…” Like most children who were reared in slums, he had a slightly different perspective than the housing reformers. “‘We kids used to have a good time,’ he said. ‘They tore down where my home was and where my pop had his [barber] shop. They tore it down to put up this high-class tenement house, this Knickerbocker Village. Most of the old-timers moved out long ago.” One has only to read the memoirs of Abraham Cahan’s novel, The Rise of David Levinsky (1917) or Mike Gold’s Jews Without Money (1930), both writers from the Lower East Side, to sense their mixed pride in the ghetto they were so desperate to escape. The emotional glue that bound the tenement-dwellers to the Old Country dissolved when the rickety buildings were demolished and replaced by anonymous, modern high-rises. Writer Alfred Kazin wrote; “I miss her old, sly and withered face. I miss all those ratty little wooden tenements, born with the smell of damp in which there grew up so many school teachers, city accountants, rabbis, cancer specialists, functionaries of the revolution, and strong-arm men for Murder, Inc.”

Some of the nostalgia of Durante and others for slum-bred ambitions seems in retrospect a disguised ethnic boasting. A personal feeling of “It was OK for me, and the other Jewish stars that made it from the old neighborhood; the rose colored glasses of the successful. When the great city builder Robert Moses met some local complainers he laughed and scoffed. “the slum is still the chief cause of urban disease and decay,” he contending that its “irredeemable rookeries had to be eradicated.” He did not buy the theory that a few dozen success stories made up for the thousands who suffered disease, lived in poverty and died of malnutrition due to unsanitary conditions. To Moses, the shanties and flop houses needed to be attacked with a meat axe, not a scalpel.

It would be just a matter of time when the majority of the old tenements would give way to the newer gov’t. assisted housing. In some ways better- with their well lighted rooms, and push button elevators- but also lacking in the atmosphere, and emotional bonding found in the ghetto houses. The new residents seemed so hit and miss: more temporary Waspy Wall Street workers, than committed ethnic family people. It has been said that only 2 pre-existing Lung Block families were rented new places in Knickerbocker Village- the rest migrant singles from upper Manhattan looking for cheap rents while they struggled in their bottom rung jobs. By then, many of the young generation also figured out ways to escape the shackles of the Lower East Side. The change would be slow, but the old tenements would soon be giving way to a new style tenement. The old Jewish residents gave way to a new mix of Black, Spanish and Caribbean peoples. The Jews began a new migration- to the suburbs. For the first time, starting in the early 1940’s, the population of the Lower East Side began to subside. People were moving out more rapidly then moving in. After World War II, increasing prosperity and tolerance, along with government housing benefits to returning war veterans, like Jack Kirby, allowed increasing numbers of Jews to fulfill their desire for single-family houses. Upwardly mobile Jews started moving out of their old communities into higher-status suburban areas.

Interestingly, by the mid-forties, the Knickerbocker Village would get its own reputation. It would be considered the Commie Commune. It was the meeting place for The American Labor Party, and other leftist groups. It was a known location to find friendly leftists and agitators. Among the lower-middle-class radicals attracted to Knickerbocker Village were Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who moved into a three-room apartment in the spring of 1942. They paid $45.75 a month for their river-view, eleventh-floor accommodations, and made use of the project’s nursery school and playground after they had children, and it was there, the bulk of evidence now suggests, that Julius conspired with Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass, to spy for the Soviet Union, but we’ve jumped too far ahead.

In late 1934, the Kurtzberg family was doing poorly; perhaps their worst ever. Work in the clothing factories was sporadic. Jacob was 17 and starting his senior year of high school. The family decided that it was necessary for him to quit school, and help earn a real salary. Jack resisted, but eventually gave in. He tried various jobs, such as sign painting and push cart vending with his Dad, but his dream was always to make his artistry pay off. His artwork for the BBR, now being signed “Jack” Kurtzberg, had improved and his confidence was such that he started submitting gag strips to magazines. Jack dreamed of going out to Hollywood, but Mama Rose swore that there were “naked women” out there just waiting to drag young Jacob down with them. The idea probably held some allure to Jake, but a mother’s word was law. Besides as Jack once mentioned “naked women never seemed drawn to him.” Summer of 1935 would find Jack answering a want ad for the Fleischer Animation Studio. They were looking for animation artists. So with his meager portfolio in tow, and most likely a glowing letter of recommendation from Harry Slonaker, Jack headed up town to 1600 Broadway. His dream of getting out of the ghetto was taking its first tentative steps.

One has to start somewhere!

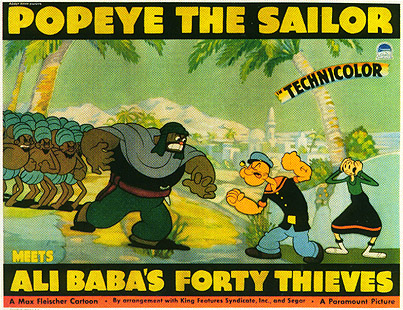

From the slums of the Bowery to the heart of Times Square and the entertainment district; things were looking up! The Fleischer Animation Studios was created in 1921, when Max and Dave Fleischer broke away from the Bray Cartoon Studios. Max was a technical wizard; he had created the rotoscope, a device that allowed cartoons to be easily transformed from live action films. He also made a staging system, the Three-Dimensional Setback, or Stereoptical Process, which allowed layers of painted transparencies to be manipulated and filmed, creating the illusion of movement and depth. The Fleischer Studios had pioneered sound cartoons several years before The Jazz Singer would revolutionize the industry, and they streamlined the animation process by creating the role of in-betweener so that their main animator, Dick Heumer could produce more work. The studios’ most famous characters were Betty Boop, and Popeye. They were second to only Disney in popularity and quality of cartoons. In 1935, Fleischer suffered a short, but devastating walkout by most of their labor force. Perhaps this was the impetus for the help wanted ad. Lucky for Jacob being Jewish wouldn’t matter to the Fleischers, their family was also from the Galicia sector of Austria, notably Krakow, and their father was a tailor. Jake was awfully young for such a position, but perhaps the Fleischer s looked at Jake and recognized one of their own.

“At one long table there was six or seven people. At the lead table the guy would draw three drawings, and then pass it down to the next person who would add in three more drawings, then he would pass it down to the next person who maybe added in checkers on the suit, and then he would pass it down to me and I would have to put the spats on or maybe the cuffs. This would go on all day and by the end of the day the character took a step—it was animation. It was a method of turning out animated movies, and it looked great at the movies, but to me I was working at a factory, just like my dad, who worked at a clothing factory. After a short period, I just walked out and quit. I didn’t say nothin’ I just quit.”

Work as a trainee in an animation studio was hardly the stuff of dreams. Doing such uncreative jobs as clean-up, and opaquing cells, Jack constantly tried to move up the artistic corporate ladder. Within a couple of months, he tested for and was promoted to in-betweener. This consisted of filling in the frames between major action poses with incremental variations to give the impression of movement. While it did involve drawing, he was still just a cog in an assembly line. Jack remembers, “I worked along a row of tables about 200-300 yards long. It was like a factory. I began to see the studio as a garment factory. I associated the garment factory with my father and I didn’t want to work like my father. I love being an individual.” Though Jack toiled in anonymity, he wanted more.

The Fleischer family pre-Popeye

On the plus side, Jack had a steady salary. He was helping put food on the family table. He could brag to his friends that he was a working artist, and point to the fact that he was partly responsible for the Popeye cartoons they were watching on screen. The other boys, seeing Jake as a success story, would press Jacob to put in a good word for them and help them get work. Concurrently, Jack continued his work for the BBR newspaper. Jack didn’t like the work but he had nothing but love and respect for the Fleischers. “The executives were fine people. Their animation speaks for itself, but it wasn’t my kind of thing.”

While the job of in-betweening may not have been glamorous, it provided Jack a unique perspective of human dynamics, and the art of movement. It taught him how the body flowed from graceful subtlety to sudden exaggerated force. Popeye’s extreme fighting perspectives and jarring explosive power gave him a solid foundation of forced perspective, and action-reaction dynamics from which he would later revolutionize the comic page. The layered depths of animated backgrounds gave Jack a hands-on knowledge of how to attain a three- dimensional effect on a two-dimensional medium. More than anything, it would be these added aspects that would separate his art from the flat illustrative art of most comic strip artists. It was this melding of illustrative art techniques learned from the masters such as Raymond, and Foster, and animation techniques learned from Fleischer that would propel Jack Kirby into the top tier of comic book artists.

In 1936, Harry A Chesler formed the first comic packaging house that hired writers and artist to produce comic material that could be sold as-is to the new books. The Chesler Co soon picked up new accounts such as MLJ and Comics Magazine Company. Within a year, Chesler became his own customer when he published his own series with Star Comics and Star Rangers. His studio features such artists as Will Eisner, George Tuska and Bill Everett. After a year he took his profits and sold his two books to Ultem and later a different book, Feature Funnies to Quality Comics Group. He returned to comic publishing in 1941 in a big way.

For a year, rumors came down that due to the continuing labor problems; Fleischer was considering a move to Florida. Mama Rose made it very clear that Jack would not be accompanying them. Jack put up little fight. So Jack began looking for a new job. With a now more impressive resume, Jack approached the newspaper strip syndicates. In the summer of ‘36, Jack Kurtzberg would go from a job where nobody knew his name, to one where he had more names than you could shake a #5 Windsor Newton at.

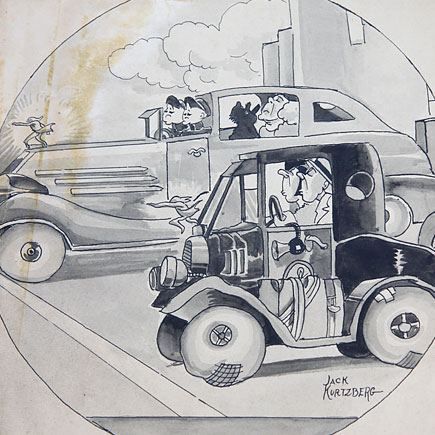

Jack showing his class warfare side even the dog has its nose upturned

In the 1930’s, America was awash with newspapers. There were literally thousands of different local papers. A city like New York had over 50 different “rags”; there were dailies, weeklies, Sundays, there were trade papers, school papers, financial papers, ethnic papers, sports papers, foreign language, and political tracts. Even social groups like the BBR had a newspaper. They all sought to carve themselves a market, some within a small niche, and some by major market blanketing. Nothing was more important to reader loyalty and identification than the funny pages. Dr. George Gallup’s first research study, released in 1930, analyzed the preferences of newspaper readers in Des Moines, Iowa. His report produced two startling conclusions concerning the Sunday comics: The least popular comic strip was better read than the main news story, and adults as well as children were avid readers of the Sunday comics section, refuting the assumption that the Sunday comics section was largely the purview of young people. Circulation could rise or fall by thousands of readers with the addition, or loss of a particular comic strip. The creators of the more popular comic strips were better known and more respected than the beat writers, sports columnists and muckrakers– and better paid! Bud Fisher, creator of the popular strip Mutt and Jeff became a millionaire after a nasty copyright fight between competing syndicates. The court awarded him the rights to the cartoon strip plus the profits from the licensed use of his characters. An early example of what would become common; court fights over the copyrights and licensed use of cartoon characters, with a rare win for the actual creator.

Elmo’s only known picture (from passport) Bud Fisher jokes at his prosperity

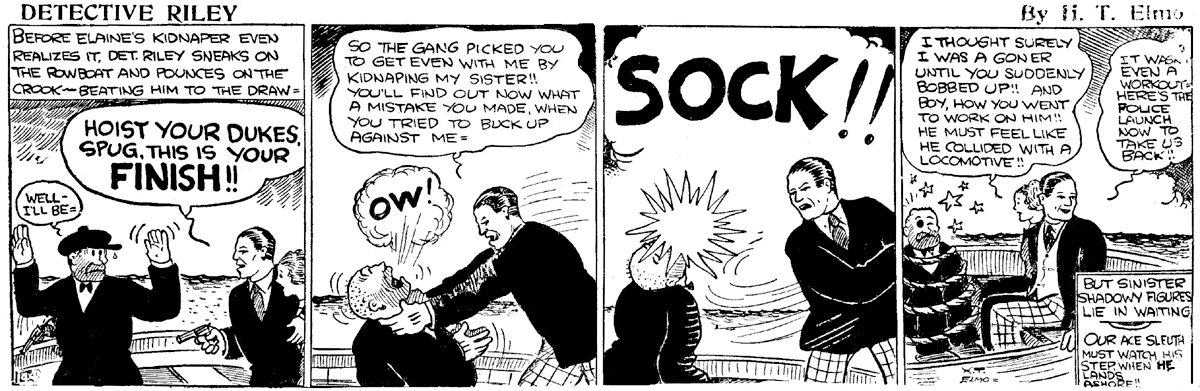

For every large metropolitan newspaper such as the New York Herald, or San Francisco Chronicle which could afford the cream of the comic strip crop from the major syndicates, there were dozens of small local papers trying to compete any way they could. One answer was to buy knock-off comic features from the many minor league syndicates that had sprung up. Just like the baseball minor leagues, these syndicates attracted has-beens, never will-bes, and the occasional rookie diamond in the rough.

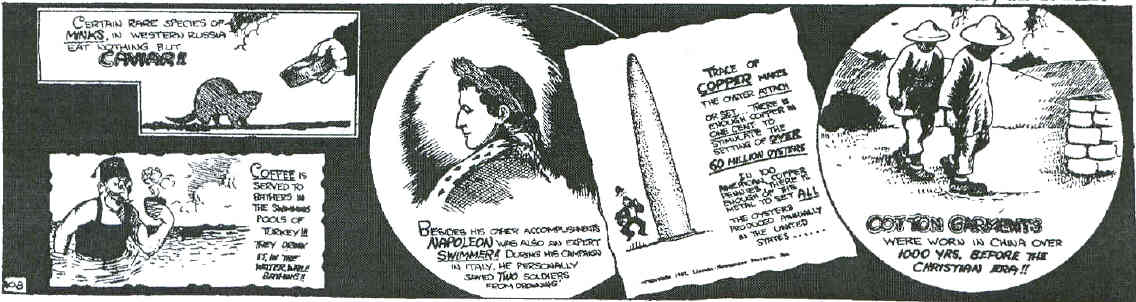

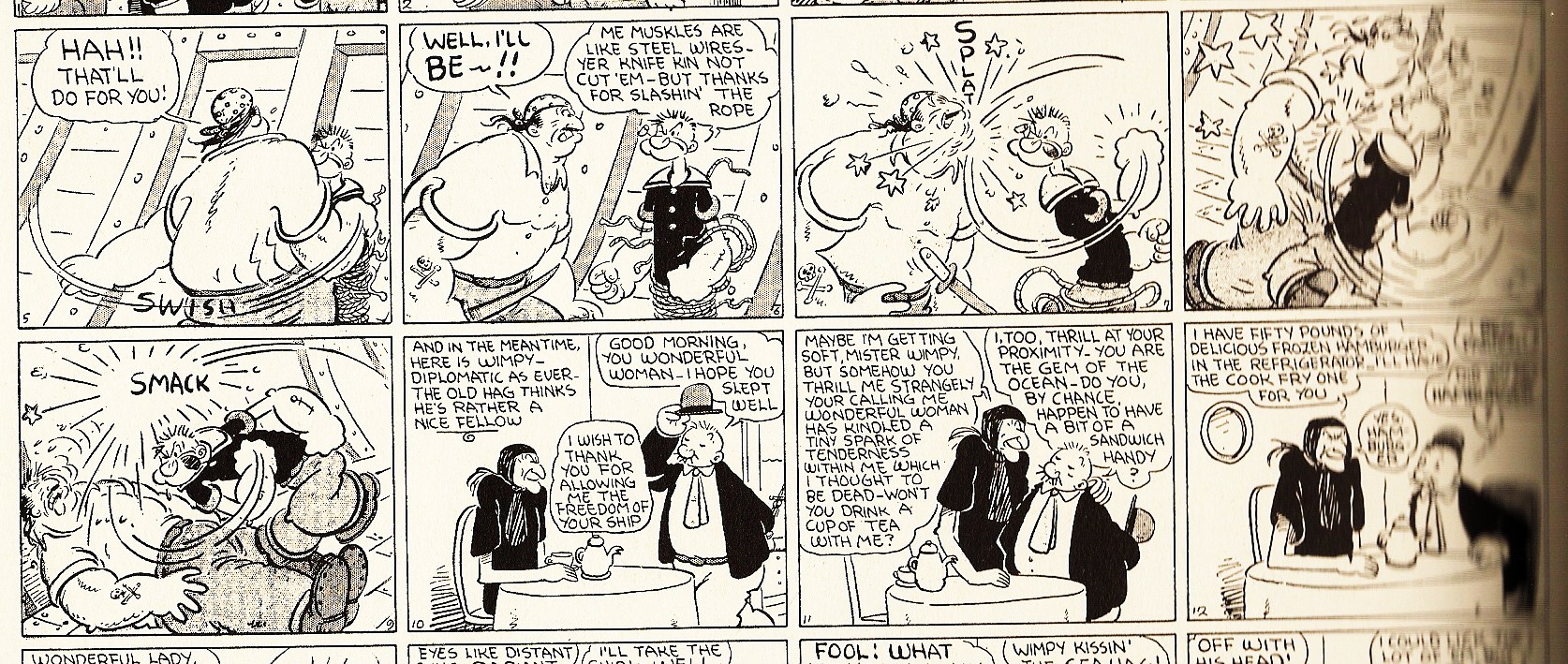

Lincoln Features Syndicate was just such a farm league operation. Run by Horace T. Elmo, it specialized in low grade clones of many of the more popular comic features. Not much is known about H.T. Elmo’s start, born in 1903 and cartooning by 1930 on unknown strips, but by 1935, his syndicate began producing numerous features for smaller market papers.

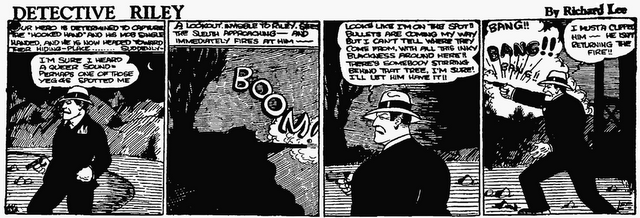

When Jack started working at Lincoln in late summer of 1936, Elmo’s firm was a thriving, though mediocre concern. They were producing more than a few ongoing strips for a wide range of small papers located all across the country. Elmo himself was a competent cartoonist working on strips such as The Goofus Family and Facts You Never Knew. Other artists were supplying a wide variety of strips such as Little Buddy and Sally Snickers. Perhaps the best of the bunch was a strip credited to Elmo, but drawn by Larry Antonette. Dash Dixon was a Flash Gordon takeoff that ran for several years. Though not as imaginative, or as illustrative as Raymond’s masterpiece, it did have energy and substance. Detective Riley was also a long running strip usually copying Harold Gould’s Dick Tracy, drawn early on by Elmo himself.

Drawn by Elmo-once thought to be early Kirby (probable lettering)

Elmo liked Jack, and was impressed by the variety of styles Jack showed in his portfolio, but Lincoln couldn’t match his salary at Fleischer unless Kirby could produce twice as many features as the other staff artist. Jack assured him he could and jumped at the opportunity. The appearance of a large stable of artists was important to the small syndicates, so the use of multiple names, and styles became common. If one artist’s work could be foisted off as that of several people, than more the better. Thus we would see the work of Jack Kurtzberg credited to Lawrence, Bob Dart, Brady, and Barton and of course, H.T. Elmo. But the name he would use most often, on several different strips was Jack Curtiss. It seemed Jack like short punchy names. Jack would explain. “I wanted to be an all-American. Much to the chagrin of his parents, most of his nom-de-plumes would be short punchy Anglo-styled names.

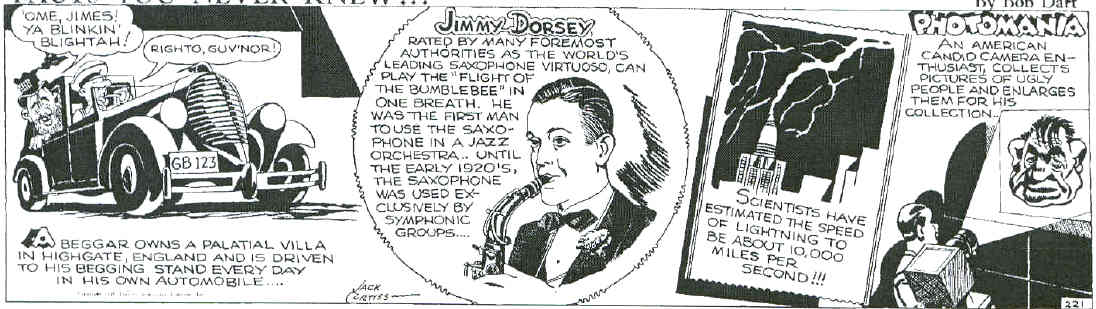

Jack immediately took over several series such as Facts You Never Knew, Curiosities And Oddities and Laughs From The Days News! These were all gag a day, Ripley’s Believe it or Not style strips that presented trivia or curiosities in a humorous, cartoony vein. On Your Health Comes First Jack used a more realistic style and a ton of research to promote physical well being. He rounded out his work supplying puzzles and riddles for the kids in Our Puzzle Corner using a sometimes goofy big-foot approach.

This variety of styles and mix of genres was just what Jack needed. The discipline learned at BBR, paid off as he applied himself like never before. His learning curve was quick and the improvement was immediately noticeable. Most noticeable was his inking, his line became more varied in width and fluidity, and he became more competent with shading and the spotting of blacks–a necessary skill to give the drawing depth and form.

Early strip note uneven and varied fonts on strip

His lettering, a real weakness early on soon became consistent, controlled, and precise. In fact, his lettering style became so unique that it is one of the easiest aspects to use when trying to trace early unaccredited art to Jack. His placement of dialogue balloons and narrative text became better integrated into the cartoon panels.

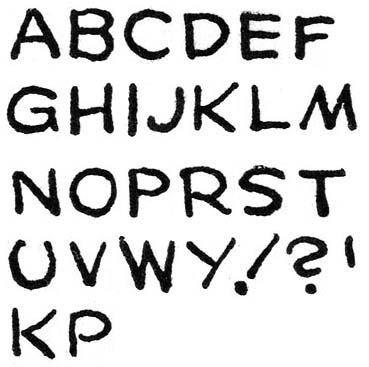

Samples of Kirby’s letters assembled by Harry Mendryk—note U, R, !, ? easy give-aways

One of the benefits of working for Lincoln was that Jake was able to draw his strips at home. Gone was the monotonous row upon row assembly line set-up at Fleischer. Jake worked at the kitchen table, around meals and other family gatherings, always under the watchful eyes of a proud Mother. Though it was noisy due to all the traffic, at least Jack had someone to bring him soup and rub his aching shoulders. It is due to Rose, and her personal scrapbook of Jack’s early strips that historians have been able to document so much of Jack’s early work. Jack’s memory for details of his time with Lincoln was sketchy, but he remembered that it was happy time–he was a working artist doing what he loved. The pay wasn’t great, but it was as far from factory work as he could get.

For months, Jack worked on these stand alone cartoon strips, learning and growing. Finally Elmo decided to increase Jack’s workload. Whether it was due to Jack’s pushing to do serial type adventure strips like his idols, Raymond and Foster, is unknown. Perhaps a demand from some of the newspapers for more action strips in addition to the gag a day features, either way, Jack was asked to produce three new action strips with continuing characters and storylines.

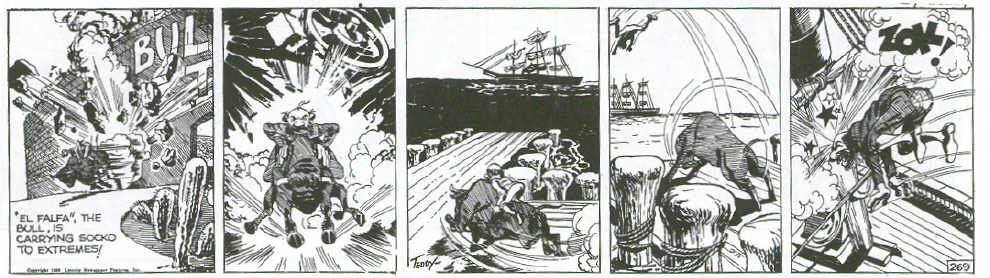

On April 8, 1937 Lincoln premiered The Black Buccaneer by Jack Curtiss, “Cyclone” Burke by Bob Brown, and Socko the Seadog signed Teddy, but all drawn by Jack. Continuing Elmo’s method of operation, none of the three strips were innovative. Black Buccaneer was a Captain Blood knock-off. There had been an earlier Black Buccaneer in a juvenile series but there seems to be no connection as a source between the two. “Cyclone” was a two-bit Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon carbon copy, and Socko was offered as a low rent Popeye.

Black Buccaneer lovely wench!

Cyclone Burke nice cinematic vista

Cyclone and Black Buccaneer did not last two full months, but not due to Jack’s art. His art on these two strips was top flight. The period costumes of Buccaneer were spot on, in a Hollywood kind of way. The female lead, Faith Robbins was a not so subtle homage to Olivia de Havilland; the female star of the Captain Blood film from just a year earlier. His backgrounds were exciting and detailed, and his characters were individual and recognizable. The line work was bold in an etched style reminiscent of Will Eisner. Cyclone’s aerial scenes are interesting with varied angles and acrobatics straight out of Wings. His sci-fi machinery, buildings and robot look right out of Metropolis or Shape of Things to Come. Given the chance, Kirby’s many hours in front of a movie screen began to pay off.

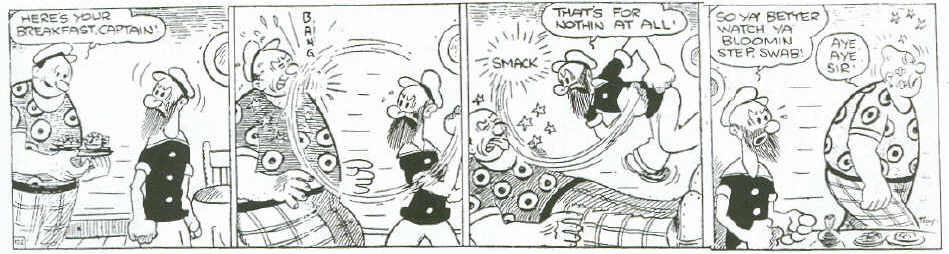

Socko the Seadog, on the other hand would continue for several years. There are several hundred samples found in Momma’s stash. Of the three strips, one could make an argument that Socko was initially Jack’s weakest work. The art was flat, with simple or no backgrounds, and little shading. The plots, such as they were, were simple slapstick gags, usually having Socko in a Popeyesque smack-down with another swabbie. It is not surprising that some of the panels were direct swipes of Segar’s squinty eyed sailor. Yet that child-like simplicity might have been its initial strength.

Socko no backgrounds, just action

swipe from Popeye becomes Socko

There was also an oddity that emanated from the Elmo studio. In 1937, there was a small pamphlet put out by banks as a premium. The Romance of Money was a collection of 23 Kirby drawn pages showing the virtues of saving money. It offered a history of money with short vignettes showing how money evolved, and how banking and finance work.

Though released in 1937, the art, format and lettering match up more closely to Jack’s work in his earliest 1936 Lincoln strips. It suggests that this might have been a set of samples for a proposed newspaper feature. When that didn’t work out, Elmo later packaged it and sold it to banks to be used as an advertising premium, not unlike other new-sized comic books. It was reprinted at least once in the 1940’s. However it came about, crude as it was, it is recognized as Kirby’s first published cartoon work in book form.

The artwork is nice but the lettering was terrible, crooked, multi-sized and uneven, barely 24 pages

Kirby letters for sure the rest is unknown probably Kirby from Mama’s stash

There is another oddity. H T Elmo had a long lasting strip called Detective Riley. For the couple years it ran it featured different pencilers—Elmo himself for a while. There is a short period with an unknown penciler, yet this same short period does feature Kirby’s lettering. It’s possible that Kirby also penciled but no evidence. The little mouse tail line for the balloon, the bubble balloon, the double exclamation points and the rounded “U” are just some of the match-ups. The artwork is too generic to tell for sure. Some have said that the ¾ male pose was a Kirby trait. There were examples of Riley in Mama Kirby’s stash book. Kirby certainly could have been aping Elmo’s preceding strips.

The work at Lincoln was steady, but low paying. Promised bonuses never appeared. Jack still had time on his hands, and time meant money. It wasn’t unusual for artists to share new job possibilities. Chesler was just the first. New comic art studios were popping up needing budding artist who would work for cheap.

day gags

A new syndicate was looking for artists. This small outfit had recently contracted with an overseas company to provide strips for a weekly British magazine. From small acorns, big oaks burst forth, or in this case, a whole forest!

Will Eisner had gotten into comic strip work in early 1936 when his friend and fellow Dewitt Clinton High alum, Bob Kane had told him about a new comic book publisher looking for art. The owner was John Henle, who ran a clothing factory, but wanted to expand into publishing. His one and only title was called WOW! What a Magazine. Samuel “Jerry” Iger, a comic veteran dating all the way back to 1934, when he supplied strips to the seminal comic book Famous Funnies, was brought in to edit this book. Iger bought several strips from Will Eisner. Unfortunately this new title and publisher closed down after the fourth issue. Will was desperate. He filled in some by working for Harry A Chesler.

Will in 1941

So in late 1936, with little freelance prospects at hand, this unlikely duo, the 19-year old prodigy, and the veteran, threw caution to the wind. Realizing the need for original material to fill the funny pages, they formed a comic art syndicate titled Universal Phoenix Features. Taking a small office on Madison Ave. and 40th Street, Eisner and Iger hired two sales reps and they hit the streets. Universal Phoenix would most commonly be referred to as Eisner and Iger Studios, or shortened to just E&I. E&I started slowly, supplying some local papers with strips, but soon got a contract with Editor’s Press to produce artwork for their overseas magazines. Its main title was WAGS, a weekly tabloid printed in the U.S. but distributed in the UK, and Australia. Editor’s Press had recently loss some British strips and needed some new features to replace them. E&I’s first strips appeared in WAGS #17, dated April 23, 1937.

Much of the earliest artwork was supplied by Eisner and Iger themselves, some from revamped strips first seen in Famous Funnies and WOW! What a Magazine, and some new. As they expanded, other artists were added such as Eisner’s school friend Bob Kane plus Dick Briefer, and Mort Meskin. Will had a routine of placing want ads in the local papers for artists and interviewing them on Monday mornings. Jack Kurtzberg, answering a newspaper ad, joined in early 1938 and was immediately assigned three strips; quite an accomplishment for an unproven artist.

Start of something big – Hawk of the Seas

Will Eisner was different than Jack’s other bosses. Unlike the older Fleischer’s and H. T. Elmo, Will was a peer, only six months Jack’s senior. Will’s parents were also recent immigrants from Austria. Born in the Williamsburg neighborhood across the city from Jack’s Lower East Side, his family would settle in the Bronx. Will’s father was a painter; he worked at times as a church muralist, and a scenery painter for Yiddish Theater productions. Work was spotty, and after an injury he opened a fur-cutting factory. It didn’t hurt that Eisner was also Jewish. Will Eisner explains, “this business was brand new. It was the bottom of the social ladder, and it was wide open to anybody. Consequently, the Jewish boys who were trying to get into the field of illustration found it very easy to come aboard.” For talented Jewish kids who had no gift for athletics (like, say, heavyweight boxer Max Baer), music (like Benny Goodman), or acting (like John Garfield and the Marx Brothers), creating comic books appeared to be a way out of poverty and into a legitimate, hopefully lucrative, artistic career. For the same reason, the field was also wide open for Jewish comics publishers.”

Will Eisner recalls:

“Jews couldn’t go to college except in rare instances, and they had to have money to do so,” as Eisner explained. “I didn’t come from that kind of background, so I ended up going into comics instead. I was like a lot of Jewish kids in the business. We had greater ambitions. As a result, we ended up expressing them in our work–and expanding the limits of the genre in the process.”

Will’s interest in art began early and like Jack, his artwork covered tablets, floors and sidewalks. When his father’s business failed during the Depression, young Will had to help out with the family finances and like other kids hit the streets selling newspapers, meanwhile grabbing free art lessons from WPA funded programs. He attended Dewitt Clinton High School, a prestigious school known for its art curriculum. Encouraged by his father, Will took some classes at the Art Students League of New York, studying under George Bridgeman and Robert Brachman. While in school, Will worked part time at the New York Journal American doing odd illustrations, and as art editor for a small magazine named Eve.

After graduating, Will found work in the advertising dept. at Hearst’s New York American and at a print shop. Hoping to expand with freelance work, it was providence that Will ran into his old high school chum.

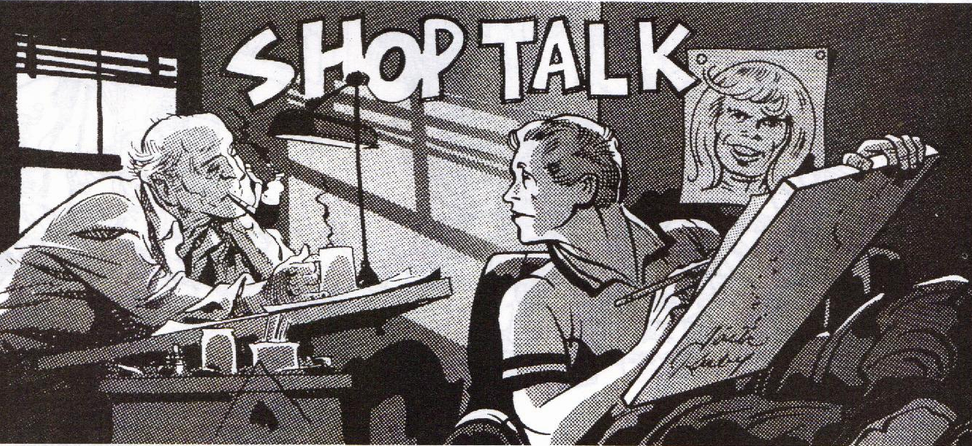

Will possessed a confidence and talent far beyond his years. Though young, the confident 6’2” Eisner was an impressive figure. Jack always marveled at Eisner and Iger’s professionalism and business acumen. More than any other mentor, Will freely shared art techniques and storytelling techniques. The studio mates shared experiences and knowledge. The Eisner/Iger studio was the closest Kirby would ever come to professional training. In a 1982 interview called Shop Talk in Will’s Spirit Magazine between the two masters, Jack confided to Will; “I knew my knowledge was limited. I felt I could increase whatever dimension I was reaching for through men like you and Jerry, because you knew the discipline, you knew your job, and that’s what I wanted. I wanted to know my job.” For his part, Will recognized greatness and considered Jack as a “top gun” from the start. Will often humorously remembered Jack Kirby; “He was a quiet young man, short, smart fellow. He always resembled John Garfield and he acted like him, but he was a very hardworking person. I enjoyed having him work for me. He was a good man.” Kirby, like Garfield could not hide his gruff, brooding working man nature.

The two men talking and drawing

Working for E&I was different than Lincoln. Instead of an artist working alone and being responsible for the complete work, the art was produced piecemeal in a studio where the artists worked assembly line style. Will explained to Canadian artist Marilyn Mercer. “I would write and design the characters, somebody else would pencil them, somebody else would do the backgrounds, somebody else would ink, and somebody else would letter. Will usually wrote the first few chapters of a new character’s story, before turning it over to other writers. “We made $1.50 a page net profit.” Will was seated at a drawing board at one end, and the others in a row of desks along the walls around the perimeter of the large room. At other times, the artist might do the full job, but always under Will’s watchful gaze. While this produced a homogenized finished product with a professional sheen, it sometimes lacked the personality and spontaneity of a singular artistic vision.

Eisner was unique in another way, as the artists improved, Will would give them more latitude to create and write their own features. The artists were the principle storytellers and they were allowed to take the scripts and rework and mould them to fit their particular style. This was unheard of at most other studios where the artists were expected to follow the scripts faithfully. This is an early precursor to the method Jack would use when he had control of his own stories.

Count of Monte Cristo was a faithful adaptation of the Dumas novel of political intrigue and revenge set in post-Napoleonic France. Jack worked in close tandem with Will Eisner on this title as detail and atmosphere were most important. Jack signed this under his adopted nom de plume Jack Curtiss. After 8 episodes, this strip was turned over to new-comer Lou Fine.

The Diary of Dr. Hayward credited to Curt Davis, was a science fiction title dealing with an evil disfigured doctor in a muddied plot involving body transference, and guest starring Death himself. This features some of Kirby’s best work; atmospheric and claustrophobic, the moody art outshone the muddy plot- a classic case of style over substance. The sci-fi milieu spotlights Kirby’s fondness for cinematic effects. Jack used a wide range of inking techniques to evoke texture, mood and depth.

His third strip; Wilton of the West (also called Wilton of West Point) was a routine rough and tumble western, full of gunfights, bushwhacking and dastardly villains. This was signed Fred Sande, and originally drawn in a loose open style, with minimal backgrounds and little detail. Jack quickly tightened up the art and experimented with shading and inking techniques. He even broke away from the rigid grid layout and varied the panel sizes. The early story is typical western lore. The time frame seems to be late 1800s, and the hero, Wiley Wilton, appears to be a generic cowboy caught in a range war. But in episode #8, Jack made a sudden stylistic change. The setting is suddenly modern times, and the ranch is visited by outsiders in a bright shiny 1940 vintage car.

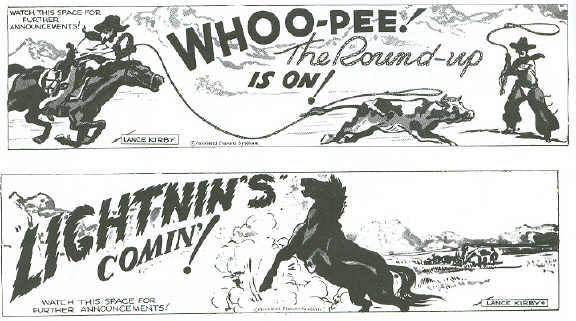

Metromount Productions wants to rent Wilton’s ranch to make a western movie. Wilton, in his best stoic Gary Cooper imitation, regretfully informs them that it can’t be done–it would interfere with the round-up. After a promise that filming would be wrapped before the round-up, and some prodding by the ranch hands, who have been promised jobs as extras, Wilton relents and the production is on.

We are next introduced to the cast of the movie, with several characters of interest. Sheldon Shwartz is the producer in what may be one of the very few times Jack went out of his way to make a character Jewish. Geoffrey Parker is the male lead and, in what would become a Kirby trademark, is portrayed as a conceited, effete snob. And in the romantic lead, we have the beautiful Marcia Merrill, every bit as snobbish, arrogant, and ditsy as her male counterpart.

Unfortunately, Jack’s part in the story ends before the story concludes, but we do get a glimpse of several themes that would play out time and again in Kirby’s storytelling. First, Hollywood sets are places of intrigue and danger. Second, male movie stars are invariably obnoxious, effete blowhards who must be brought down a peg or two by the laconic hero. And third, the female leads are star-struck vixens needing to be saved by a real man, as in Jack’s slow-talking, hard-hitting men of action. This may seem a fairly negative view of Hollywood, and it’s surprising from someone who once dreamt of going there. Perhaps this was Jack’s way of convincing himself he was better off not to have pursued that particular dream. Jack did 12 pages each on both of these strips.

One bit of Kirby iconography first shows up in both Dr Hayward, and Wilton. In both strips there is a scene where the female lead is shown sitting at a dressing table looking in a mirror while fixing her hair. In the mirror’s reflection we see someone entering the room behind her. Most likely swiped from some long lost movie, it became a Kirby staple, used in every comic genre.

Mirror, mirror, who’s in the mirror?

Later in 1937, Editor’s Press published a sister magazine to WAGS. Okay Comics had a similar format, but it also had several long running strips, such as Wash Tubbs, and Tailspin Tommy, so little new material was needed. Will and Jerry provided a few strips, but no art from Jack Kirby has been found.

Spring of 1938 would find Jack Kurtzberg busy with 2 steady accounts, responsible for 4 ongoing strips and many gag features. He was working in a field he loved, and a major contributor to the family’s finances. Life must have looked bright. In April, a new comic magazine premiered; its cover portrayed a stiffly drawn figure clothed in a gaudy circuslike caped costume, singlehandedly lifting a sketchily drawn car and smashing it on some rocks. Its bold title aside, the garish primary coloring, and primitive rendering did little to portend the revolution it would soon ignite. Action Comics #1 was the fuse, and Superman was the spark! Jack would claim that the first appearance of Superman was when he knew that comic books had truly arrived.

Jack’s time at E&I would be short, perhaps no more than three-four months and only producing 32 full pages of art, but the influence was deep and long lived. Why he left so soon has never been explained. While there seems to have been no rancor, there may be some clues in Jack’s recollections. Jack expanded; “Eisner and Iger were energetic, efficient and they weren’t out to be friendly; they were out to produce. Eventually, we all became personal friends. It was a time for thorough professionals.”

When Jack reminisced about Eisner/Iger he never described working there as a “fun” time. It was just a job. Jack said; “I remember all the guys. Although we all liked each other and we’d trade stories and things, we never horsed around. We always felt that we had to do a job.” Will himself realized there was a wall between him and the artists. “There was something of a social life within the studio setting; he reminisced in an interview for the Comics Journal. “But one of the problems I had was that I was about the same age as these guys; and it was a little difficult for me to be part of their social activity. When they’d go out and have a beer at the end of the day, they never invited me along; I learned to keep in my place so to speak.”

Will asked Jack in an interview; “Were you ever close, back then, to Lou Fine?” To which Kirby answered, “No, I don’t feel that I was ever close to anybody.” Lou Fine was perhaps the first superstar draughtsman to come to comic books. Born in 1914 and raised in the Brooklyn area of NY. Hobbled by polio at a young age, the boy turned to art. He attended the prestigious Pratt Institute. He turned up at the Eisner and Iger studios just after Jack Kirby, and immediately impressed with his clean illustrative style reminiscent of J.C. Lyendecker infused with Alex Raymond’s flexibility. His feel for anatomy and dynamics was unparalleled. When Jack left E&I, it was Lou Fine who took over the strips. For the next few years Lou Fine would become the yardstick with which every comic artist was to be measured. His work on Fox’s Flame, and Fiction House’s Red Bee are artistic marvels to behold.

Lou Fine’s elegance and energy

Jack preferred solitude by nature, and while he could admire Eisner’s professionalism, and talent, in his heart he must have rebelled against the assembly line nature of the E&I studio. He liked his fellow artists, but his creativity preferred the quiet of his kitchen table. Perhaps the rows of interchangeable artists working on an assembly line reminded Jack too much of his time at Fleischer, and the gnawing fear of ending up like his father doing piecework in a factory.

There might also have been a financial consideration. The weekly checks from E&I were meager. The long hours spent traveling to, and working at the studio forced Jack to do his Lincoln strips later at night and on weekends. Artist George Tuska talks about the situation at the studio and how the demand became overwhelming. “The artists load continued to grow, requiring them to take work home with them.” At five dollars a page, Tuska recalls that it just wasn’t enough. One day, he went to lunch with some of the other artists when he stood up and told them he had to “meet someone”. He never returned. He ended up over at the Chesler Studio, where he was soon joined by Charlie Sultan, who had left for the same reason.

Summer of 1938 would find Lincoln once again Jack’s sole account. Incredibly, soon after Jack left, Eisner and Iger hit paydirt. The pulp magazine publishers were in a funk. Sales were dropping, and they were looking for a new direction. Comic books offered them just such an avenue. From its halting creation in 1933 as an advertising premium for manufacturers, comic books had grown exponentially. At first reprinting the better known comic strips from the newspapers it quickly reached a point where original material was needed. Who better to look to then those minor league syndicates that already had cheap source material and cheap artists ready and waiting? Cheap being the operative word!

From All In Color For A Dime, (Ace Books 1970) by Ted White;

The early comic book originals were, for the most part, awful. They set out to imitate the reprints and often a six-page story would have a running head on each page in imitation of the Sunday reprints, each page of which required a running head originally. But surely the artists and writers who produced the new material were far more poorly paid—even if they received the same amount which the creators of reprints were paid. The reprints were earning their big money from newspaper syndication; the new material made what little it did solely from comic book publication. Standards quickly fell, and I think it is significant that even now they have not been entirely regained. Today, in most cases, the comic book is no more than a training ground for newspaper-strip artists.

It must also be said that comic book publishers were, all in all, thieving, grasping lot. Not to dwell too long upon the point, they were crooks. In many instances, they were men with a good deal of money, recently earned during Prohibition, who were seeking legitimate businesses into which they might safely move. Comics—and pulp magazines—seemed like a good bet. These men had learned their so-called business ethics in a rough school. They applied them across the board in their new businesses.

The first rule was, Do it cheap. Find cheap labor, pay cheap prices. Low overhead. The results were predictable—in a few short years the bad drove out the good.

Put in simple terms, most of the work being done for comic books by 1940 was being done by teenage boys, some still in high school, some dropouts. Many were enormously talented, but most came from lower-class backgrounds, were willing to work cheap (the Depression was still being felt) and were easily exploitable.”

Lou Fine was one who left the comic business early to work for advertisers.

Jack continued the gag-a-day strips – the last panel looks like a comicscope

Fiction House was just such a pulp publisher, founded by Thurston T. Scott in the early 1920’s. The titles such as Action Stories, Fight Stories and Planet Stories were trite but they filled certain niches. The Great Depression had slowly eroded its sales base, and by the late ‘30’s Scott realized he had to diversify. Whether Scott approached Eisner and Iger, or one of E&I’s salesmen approached Fiction House is unknown, but in the summer of ’38, Scott decided to publish a comic book called Jumbo Comics with Eisner/Iger providing the artwork. The first issue contained reprinted strips from WAGS Magazine. Headlined by Mort Meskin’s Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, and Will Eisner’s Hawks of the Seas, it also marked the first published comic work by Jack Kirby when it reprinted 4 pages each of Wilton of the West, Count of Monte Cristo and Diary of Dr. Hayward. Issue number two would feature Jack’s first artwork on a comic book cover, when a panel from Wilton of the West was featured. It is doubtful that Jack was even aware of this. When the WAGS inventory ran out, the Eisner and Iger studio would soon be producing original art for Jumbo Comics, and the careers of many comic book legends would blossom. Lou Fine, Mort Meskin, Dick Briefer, Bob Powell, George Tuska, Reed Crandall, and Nick Cardy are just a few who would erupt from this farm system and go on to dominate their chosen profession. For better or worse, Jack Kirby had left a couple months too soon to be a part of it.

At Lincoln, Kirby continued applying the techniques that he had learned from Eisner. Socko, which began as a simple gag a day Popeye riff, would evolve into a comedic adventure strip with storyline continuity, and recurring characters. The tales became funny little travelogues that would take Socko to all points of the earth. The art became suffused with energy, detail and finesse not found in his previous work. His inking took on subtlety and atmosphere as he experimented with shadows, silhouettes and textures.

In late 1938 Kirby worked on another strip, a cute slapstick adventure strip titled Abdul Jones. Signed Ted Grey, it featured tales of a teenaged wanderer and his bespectacled mule. During their travels, they meet such wacky luminaries as the twelve foot bandit Katchaz Katchkhan, Josef Welchmore the Bagdad bookie, and Myrtle, the toast of a Sultan’s harem. It’s not known if it was ever published, but the existing samples show Jack was developing a facility with broad humor and caricature.

The tenure at Eisner/Iger may not have worked out, but it certainly didn’t turn Jack off to the idea of freelancing. November 1938 would find him moonlighting for another small firm. Associated Features Syndicate was run by a gentleman named Robert Farrell. One of those men that while never a major player would circulate throughout the comic industry for many years. Farrell was an acquaintance of Jerry Iger’s, possibly a writer at E&I, and it may have been via this relationship that he hooked up with Jack Kurtzberg or simply a coincidence when Jack answered an ad. Either way, one must assume that Jack’s work on Wilton of the West impressed Farrell enough to offer a new western strip to him.

Jack’s first Bigfoot strip

Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider was an obvious Lone Ranger replica. This version of the masked vigilante was set in the mythical town of Three Forks, Texas. In place of a trusty Indian partner, we get a trusty, if somewhat befuddled Mexican partner, Diego. Jack signed this as Lance Kirby, his first use of Kirby.

The strip’s most redeeming feature was Kirby’s continually improving art. For the first time, he was working on a daily strip rather than a weekly, and the rhythm seemed to keep the artwork fresh and consistent. His panel constructions were far superior to his earlier work and the variations of angles and perspectives made this a more enjoyable read. His figures were set in a wider variety of poses and depths. Jack was expanding on the cinematic techniques he had learned from Will Eisner. This would also mark the first time that Kirby would work with Craftint Duotone paper, a specially treated paper that when specific chemicals were applied produced fine lines at varying angles. When reproduced it gave the illusion of shading gradations. This added depth gave a more illustrative finish with a more nuanced range of shading.

City boy likes horses!

Work on Lightnin’ was to be short lived. The strip, premiering on Jan. 3, 1939 would feature Kirby art thru the first story arc into mid February. It was customary for comic strip stories to be broken into a six-week format. Jack had started a second story line wherein the time frame mystically changes ala Wilton of the West from late 1880’s to modern day. These never saw print, but thanks to Momma Kurtzberg’s hoarding, these lost strips have been recovered.

Jack was back with Lincoln his sole account. Among his other assignments he supplied some papers with editorial cartoons. In 1937, Kirby had begun doing some of the art chores, usually signing them Davis or Jack Curtiss. These mostly concerned local politics, or social reform and Elmo kept a close eye on the content, yet at least once Kirby was called out for doing some editorializing on his own.

Jack loved his politics and current events

That low rumble back in Europe had erupted into a full scale roar. In early 1938, Germany had annexed Austria, Kirby’s ancestral homeland. By late ’38, Hitler’s might was pointed at Czechoslovakia. The world took notice of this new threat. On Sept. 30, 1938 with the signing of the Munich Dictate, Hitler had wrested control of the Sudetenland territories of Czechoslovakia, and effectively the whole of the Czech state. In an act that would live in infamy, Great Britain’s Neville Chamberlain proclaimed that with the signing of the agreement, they had secured “peace in our time.” Less than a month later, German troops entered Czechoslovakia, and on March 16, 1939 Hitler completed his conquest. An outraged Jack drew and published an editorial cartoon portraying Adolf Hitler as a grinning snake, with his belly full of the swallowed meal of Czechoslovakia. Patting his head in acquiescence was the dapper Neville Chamberlain. Despite the displeasure from Elmo- probably more due to protocol, than to the views expressed- Kirby had become, at least in spirit, the peer of one of his idols, editorial cartoonist Rollin Kirby. “I got bawled out for that. My boss said “You’re only 19 years old. You don’t know enough about politics and those things.” And I said, “That’s true, but I know a lot about gangsters. “ To Kirby, Hitler was just another gangster.

Early 1939 and Robert Farrell had bigger fish to fry, Just as Kirby left to return to Lincoln, Associated closed down; but not before Farrell managed to sell the reprint rights of Lightnin’ to Famous Funnies. In issue #61, cover dated Aug. 1939 there appeared a full page ad telling the readers in big bold letters that Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider was coming in next month’s issue. For the next four issues Jack’s strips appeared, making it the second time that his reprint art was available in the newsstand funny books.

There would be other opportunities—from fly by night outfits hoping to strike it rich. Most promised payment when they sold the product, but few ever made it that far, and Jack had a portfolio of unsold ideas waiting to be used.

Kirby’s Socko improved with age getting shadows, details and backgrounds

For most of 1939, Jack soldiered on at Lincoln; meanwhile the comic book industry was ablaze. The fuse that was lit with Superman in Action Comics #1 finally reached the powder keg. Revolutions don’t begin with great thoughts, or bold actions, they grow from need, organically, slowly, mostly by accident, and usually by the last people expected. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster weren’t revolutionaries; they were small, shy, geeky sons of Jewish immigrants struggling to make a mark in their world. Both born in 1914, they became friends when the 10 year old, Canadian born Shuster moved to Cleveland, Ohio. Both introverted, they shared a love of the sci-fi pulps and while working on the Glenville High School newspaper, they began creating their own characters and stories.

Early S&S plus inspirations

In 1933 Jerry came up with the idea for Superman, based on themes drawn from the pulp character Doc Savage, and some from novelist Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. The idea of a crime fighting avenger was deeply ingrained in young Siegel, ever since his father had been senselessly murdered in 1930. Joe’s art was crude, in a Roy Crane style, but it served the subject matter, and simple tales. Jerry and Joe also created a portfolio of other strip ideas.

The boys sent their strip proposals to many of the publishers, and syndicates; and all of them rejected it. For a while, Jerry thought of replacing Joe as artist. There was a short period where Superman might have been published by a small time publisher, but the company went out of business first. He was pitched unsuccessfully as a newspaper strip for the McClure Syndicate. Jerry and Joe did eventually get work for Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s nascent publishing company, National Allied Publications. In mid 1935, their Doctor Occult and Henri Duval strips would appear in New Fun #6. As Wheeler-Nicholson added titles, the wonder boys kept cranking out new strips; Federal Men for New Comics and Spy and Slam Bradley for Detective Comics. Superman was shunted aside.

Major Nicholson’s concerns floundered and by late 1937 he was forced out. The business ended up in the hands of its printer, Harry Donenfeld and his chief accountant, Jack Liebowitz, who renamed the company Detective Comics Inc.

They decided to expand and add a fourth title. Before leaving, Nicholson had been doodling around with a new title idea, Action Comics. They needed new material, and the editors were scraping the bottom of the barrel. Editor Vin Sullivan talked to his friend M. C. Gaines who remembered the rejected strip that was sitting around gathering dust. With little expectation, Siegel and Shuster were asked to take their rejected Superman strip, cut it up and format it to the size necessary for a comic book. They were paid $130 for the property. They have been portrayed as just teen aged naifs slickered by the big corporation, but in reality, they were both 23 years old and veterans of working three years for this very same corporation. A panel was taken and adapted for the cover. Harry Donenfeld looked at the cover and became chagrined, no one would accept this circus costumed alien. It was too ridiculous, too crazy!

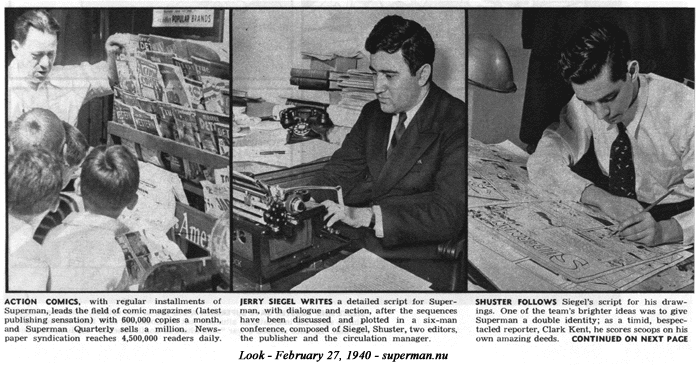

Action Comics #1 sold surprisingly well, not great but better than expected. The next 3 issues would have covers featuring other strips, and the sales continued to spiral up yet no one had a clue as to why. DC published a survey in Action Comics #4 asking what the favorite features were. Issue #4 skyrocketed in sales, quickly reaching the half-million mark. Out of the over 500 replies, over 80% listed Superman. Superman would again be cover featured on Action Comics #7, and the comic’s sales continued to grow. Word from the rack jobbers got back to the editors; the kids were demanding the comic with Superman in it. By issue #9, the cover featured a blurb; “In this issue, another thrilling adventure of Superman”. He got his own book a year later. Comic books had a phenomenon; a character and a genre to call its own. Comics had a recognized creative super team.

Getting one’s own – It’s not Rembrandt, hell, it’s not Foster but it worked.

In an article in Liberty magazine, a writer reflects on Jerry Siegel in words that could just as easily been about Jack Kirby. “Jerry, being undersized and undernourished found himself considerably pushed around by the neighborhood toughs. As he absorbed black eyes and beatings, Siegel lived in a dream world of muscle men, lapping up the deeds of Hercules, Samson, Tarzan, Doug Fairbanks, and sundry dime-novel superheroes, dreaming of a day when he could hang one on the eye of a tormentor himself.” So his response was to create a Man of Steel who, according to Siegel, would “smack down the bullies of the world.” Jerry and Joe became symbols of the little guy fighting back. This would be followed with articles in Saturday Evening Post, and Look magazine. The Cleveland wonder boys were a smash.

Now costumed crime fighters weren’t new, The Shadow, and Black Bat had been favorites in the pulps, the Phantom, a hero in the pulp tradition, first appeared in 1936, in newspaper strips, as did the Clock, in Funny Pages, but a costumed alien who bounced bullets off his chest, and could knock down airplanes, yes this was new, and it was a phenomenon. As with all phenomena, imitations were soon to follow. Publishers are nothing if not mimics, if something sells, duplicate it.

Frank Dorth, an artist who started in the forties and spent a lifetime in comics had this to say;

“My biggest complaint about the New York comic book publishers in the 1940’s was that they were all like a herd of circus elephants. They grabbed the tail of the one in front of them and followed each other around in a circle. They were not interested in quality, only what some accountant told them was selling.”

“I think that there’s a cultural thread underlying the superhero concept,” says Will Eisner, whose The Spirit is still being reprinted, more than 60 years after its creation.

“The superhero has his origins in the folk hero. He represents an attempt to deal with forces that are considered otherwise undefeatable, and that ties in somehow with the n’shama (soul) of the Jewish people. Although we may have thought we were creating Aryan characters, with non-Jewish names like Bruce Wayne, Clark Kent and my own Denny Colt, I think we were responding to an inner n’shama that responds to forces around us — just like the story of the golem in Jewish lore.”

“If you think about it,” Eisner continues, “all of Jewish cultural history has been based around Jewish cultural fighters, like Samson and David. Now, in the 40s, we were facing the Nazis, an apparently unstoppable force. And what better ways to deal with an anti-Jewish supervillain like Hitler than with a superhero?”

“I first met (former partner) Joe Simon just as Superman came out,” Kirby recalls. “It was an instant hit. Publishers suddenly came out of nowhere, all wanting someone to create another Superman.

Legend has it that Victor Fox was at various times a dandy, an ex-ballroom dancer, a shipping magnate, a stock broker and an accountant at Detective Comics Inc, (he wasn’t) who, upon seeing the success of Superman dropped his pencil and immediately started his own publishing house. True or not what is known is that Victor Fox had a shady background. Indicted in 1920 for shipping fraud, he was indicted again for a fraudulent stock scheme when the Stock Market fell in 1929, he had gotten into publishing as early as Dec.1936, His offices were in the same building as DC Comics; his on the seventh floor, DC’s on the ninth. There was even a project where DC’s President Donenfeld partnered up with Victor Fox, though the specifics are unknown. The only publication Fox had in early 1939 was an astrology guidebook, published by Bruns Publications and it was distributed by Independent News Company, the distributing arm of DC comics. In testimony from Jack Liebowitz, he and Victor Fox would meet almost daily in the Independent News Postal room and go over the daily sales reports sent in from the sub-distributors. It was no surprise to Victor Fox that Superman’s sales figures were continually rising.

Intrigued by the success of Superman, Fox started his own comic company; Victor Fox, a British émigré, had no art or comic background, but he had a silent partner; Robert Farrell, Jack Kurtzberg’s old boss at Associated Features Syndicate. Farrell contacted his friend Jerry Iger and E&I was put to work creating new characters. It has been reported that Jerry Iger went over to DC and walked away with copies of their books—including Action Comics #1.

The first title was Wonder Comics #1( May 1939). The cover feature was a colorful character named Wonder Man, flying through the air, smashing an airplane. The character was remarkably similar to DC’s Superman; for a very good reason. According to Will Eisner, Victor Fox had been adamant that he wanted a duplicate of Superman. Not surprisingly, DC immediately got a cease and desist injunction and sued Victor Fox. This would be Wonder Man’s only appearance. Issue #2 would feature Zarko the Great, a Mandrake the Magician knock-off. Fox doubtlessly had no worry about the creators of Mandrake suing him, by then there were so many Mandrake copies that no one cared, and besides, Mandrake was a rip-off of a real practicing magician, Leon Mandrake.

The suit by DC may have put the kibosh on Wonder Man, but it didn’t slow down Victor’s demand for super heroes. Retitling Wonder Comics into Wonderworld Comics, issue #3 would introduce the Flame, a hero who could control fire. Elegantly drawn by Lou Fine, this character would last for years. Mystery Men Comics #1 August 1939 would debut three new characters, Green Mask, Blue Beetle, and Rex Dexter of Mars. By the Fall of 1939, Victor Fox was publishing four monthly titles, and Eisner/Iger was working overtime. Jack’s colleagues at E&I had hit the big time. In addition to their work for Fiction House, at Fox, Lou Fine was doing The Flame, Dick Briefer was drawing Rex Dexter, Bob Kane on Spark Stevens, Bob Powell delivered Dr. Fung and Will Eisner was doing more strips than humanly possible. Lou Fine became “the” cover artist at Fox Publishing.

The lawsuit over Wonder Man was heard on April 6, 1939, with Fox losing. He would appeal. Despite Eisner’s testimony backing Victor Fox’s claims the relationship between the two became strained; it slowly deteriorated. After Fox lost his appeal they finally parted in late 1939, with Fox owing Eisner/Iger a large amount of money. Perhaps not coincidently, Eisner and Iger broke up at the same time with Will going off on his own to produce The Spirit, taking half the staff with him. Iger’s half continued on. Victor Fox began hiring his own staff. Pros, such as Bert Whitman, a seasoned newspaper gag man would introduce new strips such as U. S. Navy Jones, and Dr. Mortal, and Don Rico produced Flick Falcon. Rank newcomers like Jim Mooney would bring forth The Moth, soon to be squashed by DC for being too Batman-like. Fox also began raiding E&I’s artists, with Pierce Rice, Dick Briefer and Louis and Arturo Cazeneuve joining ranks.

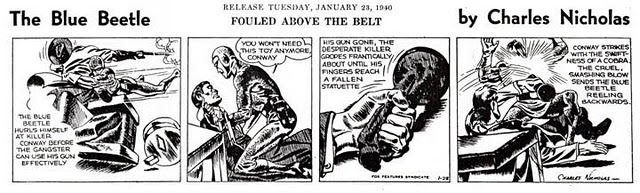

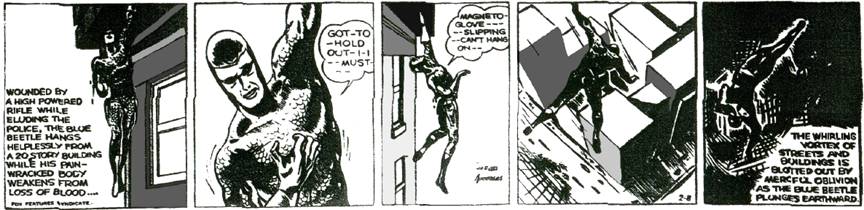

Fox Publications was slowly taking control of its own material, and had carved a nice market share for itself. Yet Victor Fox wasn’t satisfied; Superman had become a cottage industry! The strip continued in Action Comics, and expanded with its own eponymous title. Superman branched out with a syndicated newspaper strip, and a radio show. The combative Victor Fox would not be outdone. In late 1939, Fox’s most popular character, the Blue Beetle, was given its own title; next in line was a newspaper strip to be followed by a radio show.

It’s not known just when Jack Kurtzberg started at Fox; perhaps Robert Farrell had contacted him early on to help with in-house ads, and production clean-up, or maybe in Fall ’39 when it became obvious that Eisner/Iger would no longer be supplying artwork. What we do know is that by November, Jack was doing production work and ad copy. More important, he was tabbed to draw the new Blue Beetle newspaper strip.

The fabulous Fleischer Cartoons

There appears to have been some overlap with Lincoln, with Kirby drawn Facts You Never Knew, and Socko The Seadog strips dated well into Dec. 1939, but it seems clear that Lincoln closed shop by the end of ’39. Jack once stated that Elmo closed up to head to Canada to mine uranium. There are some samples of Lincoln strips, including Socko the Seadog in papers well into 1940 and ’41, but these appear to be earlier strips running later in new papers.

Working for Victor Fox was a major dose; he was eccentric, volatile, and incredibly full of himself. Will Eisner remembers Fox. “Fox was a very, very shifty, fast-footed business man who would create fictitious names because he was always afraid of being sued.” He sarcastically added; “I learned a lot about “business” from dealing with him.” Al Feldstein recalls; “Victor was short, round, bald and coarsely gruff, with horn-rimmed glasses and a permanent cigar clamped between his teeth. He was the personification of the typical exploiting comic book publisher of his day- grinding out shameless imitations of successful titles and trends, and treating his artists and editors like dirt.”

Jack Kirby recalled Fox slightly differently. “I didn’t respect Fox as a professional. I respected him just as a boss. I thought he was a great character…..He was Edward G. Robinson. I remember him walking back and forth watching the artists all the time like a hawk and just saying, “I’m the King of Comics”. And we would look back at him and actually he was a joy to us because he made working fun. He was a character in the full sense of being a character.” Kirby reiterated; “I couldn’t picture myself liking a guy like Fox, but I did. I genuinely liked Victor Fox.”

Doing the Blue Beetle strip was an important step for Jack; it was his first work in an urban milieu. He could finally draw from his personal experiences when drawing buildings, vehicles, furniture and clothing. The cityscapes and interior scenes became a major part of the series. The Blue Beetle was also Jack’s first attempt at a costumed hero. Created for the Eisner studio by 18 year old Charles Wojtkowski, under the pen name Charles Nicholas, the Beetle was a pulp style vigilante reminiscent of the Green Hornet. While possessing no super powers (yet) he was acrobatic and fearless. He also possessed some neat gadgets that would make for some exciting scenes.

Lots of action, and Alex Raymond swipes

His alter ego–a costumed hero requirement– was Dan Garrett, the ubiquitous Irish flat foot, who when the legal system failed, would don a blue chain mail union suit, a domino mask, and holster his gas gun to ferret out evildoers and beat a confession out of them. Surprisingly, this didn’t sit well with the authorities, and he was hunted as a danger to the good folks of York City

The storyline for this inaugural newspaper strip is disappointing. It offered no back-story, no origin, nothing to explain how and why the Blue Beetle came to be. Surprisingly, the Beetle is out of commission half way through. The main featured character shifts to Charley Storm, a newspaper reporter hot on the trail of the Blue Beetle, and the crooks who killed the D. A. While the Beetle is wounded and out of action, it is Charley who takes over, and tracks down the criminal mastermind. Plus, Charley gets the girl! One would think that an inaugural story would feature the Blue Beetle as the conquering hero. Ignore the plot, the attraction here was not the story, it was Kirby’s first shot at a costumed hero, the genre that would eventually propel him to greatness, and he does not disappoint. The art is energetic, fluid, bold and experimental. Jack’s use of silhouettes, high contrast shadows, close-ups, and large group shots, was miles ahead of his work from just a year earlier. The Blue Beetle never looked better!

While at Fox, Kirby continued to freelance. Bert Whitman, an itinerant cartoonist and one of Jack’s colleagues at Fox decided that he wanted to open his own art studio, ala E&I. He had contracted with Frank Temerson to provide the art for a new publishing venture. Temerson began his publishing career when he teamed up with a gent named Irving Ullman to buy the Comics Magazine Company; an early publisher of newspaper reprint strips style comic books. Frank Temerson, was a former city attorney for Birmingham, Alabama. He and Ullman were suspected Mob men who ran a number of businesses to launder the Mob’s money.

Nice figures, different views and deep perspective

They would often use phony addresses and switch their company’s names frequently to confuse the authorities. After a year, they sold their concerns to Centaur Publications. Jack offered up a sci-fi strip titled Solar Legion. It’s possible that Jack had been tinkering with the idea as a newspaper strip proposal, perhaps one of the earlier unsold ideas he had stashed. Some of the strips appear to be cut and repositioned to fit a comic size page, but as published, in Crash Comics #1, cover dated May 1940, it was Kirby’s first original concept to be featured in a comic book. Whitman would reach higher renown when he became the first person to gain the rights and draw the exploits of the Green Hornet. The art on Solar Legion features Jack’s boldest inking to date; lush and organic. Kirby seems to have come to terms with using a brush instead of a pen. The thickness of the lines and the natural free-hand flow makes a striking contrast to the finer pen delineation on Blue Beetle. The added darkness worked perfectly on the space opera milieu, giving the needed depth, solitude, and high contrast befitting the genre. Kirby’s strip would appear in the first three issues of Crash Comics, and then be continued under another hand. As seen on the original proofs, the work was signed as Jack Kirby, his first time with this pseudonym, unfortunately the signature was stripped out when published.