A Failure To Communicate – Part Six

Thanks to Mike Gartland and John Morrow, The Kirby Effect is offering Mike’s “A Failure To Communicate” series from The Jack Kirby Collector. Captions on the illustrations are written by John Morrow. – Rand

Part Six was first published in TwoMorrows’ August 2000 Jack Kirby Collector 29.

“Less is More.” Never thought about it, really; just another catchy phrase used by advertising people to try and convince you to buy something—that you were getting something special. What could it mean? Well, I guess it could mean something like concentrated fabric softener, or if a seller was trying to convince a buyer that their “new reduced-size” product was just as good as the previous size (except the price remained the same, or was increased, of course). But it wasn’t until I began to research the layout work that Jack Kirby did for Marvel in the Sixties that I realized what it also could mean.

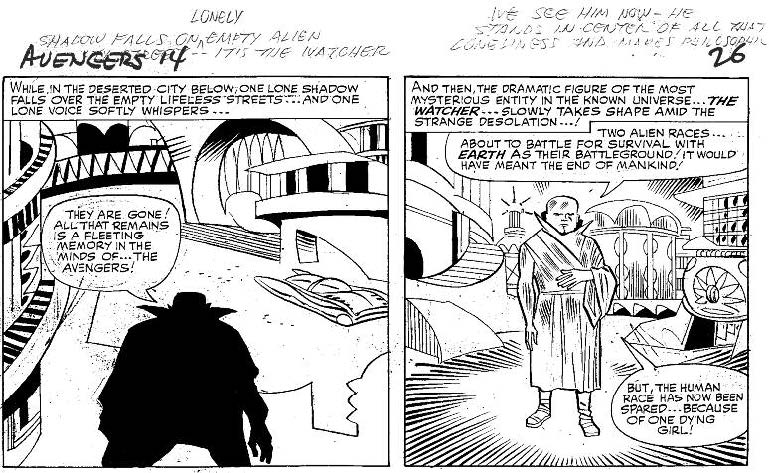

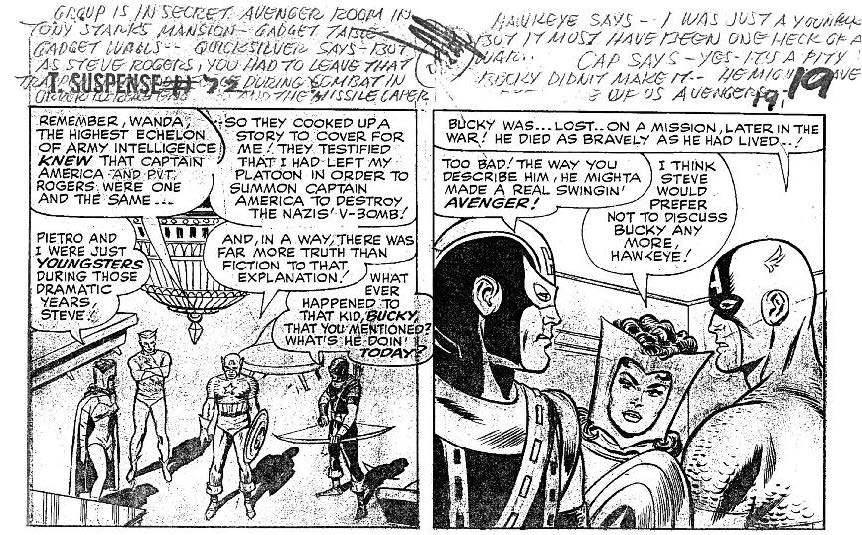

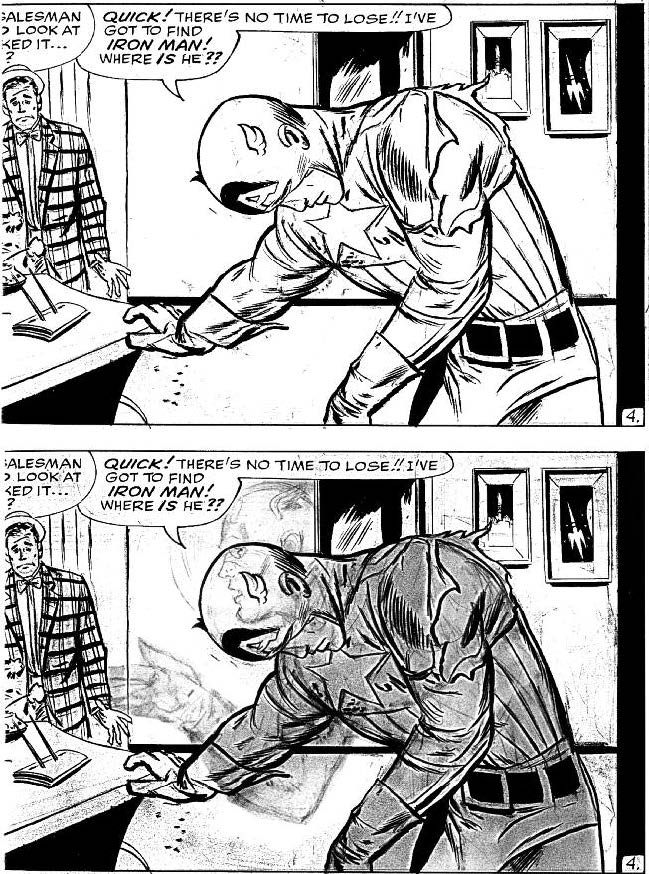

Jack’s margin notes from Avengers #14; layouts by Kirby, pencils by Heck, inks by Chic Stone. Jack was brought back in to set the tone and direction for the series, even though he stopped being the regular penciler on it with #8.

Personnel-wise, Marvel was in a state of flux by the mid-Sixties. Due to the tremendous increase in popularity of the new Marvel line, Stan Lee was in constant search for creative people to help lessen the load; he was also seeking inroads to release new titles while under distribution restrictions. By 1965 books that originally showcased one super-hero found themselves sharing with another; or were dropped totally in favor of a new series. Storylines began to change to a multi-issue, serialistic format. New artists were introduced; some stayed, others didn’t, or stayed but in a different capacity, such as inking, coloring, or production. The artists who were to pencil these books had to be indoctrinated to the “Marvel method” of story production. Due to the pressing deadlines, and foreseeing that some might have problems conforming in so limited a time, Lee decided that the best course to take would be for someone to work with these artists who could help them learn to work “Marvel method.” Well, who better than the one who unknowingly created it, Jack Kirby?

To digress for a moment, it is my opinion that the “Marvel method” was not so much a creation as it was an advantageous development. Lee states in a 1977 interview that it came about in the Sixties, but in a more recent interview with Roy Thomas in Alter Ego, Roy convinces Lee that it must have occurred earlier, during the pre-hero monster era. This makes more sense as it coincides with the return of Kirby to Marvel on a regular basis. In my opinion, once Lee realized that Kirby needed little or no prompting to get a good saleable story out of him, he gave Jack the leeway (no pun intended) to develop characters and concepts that an otherwise full script would have restrained. When Lee also realized that he could adapt that type of collaboration with others, and get better stories from them (and free himself from writing scripts), the “Marvel method” was born.

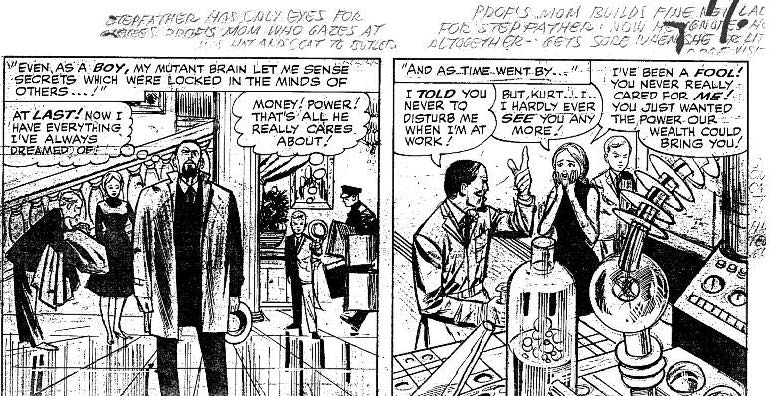

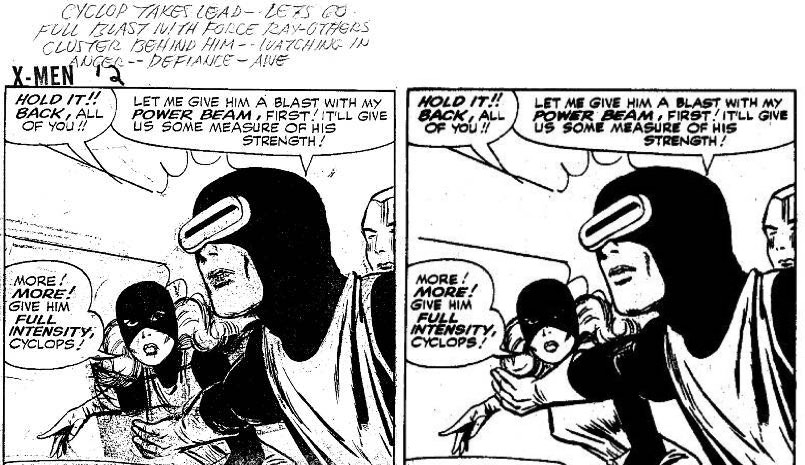

Original art from X-Men #12 showing Jack’s margin notes and layouts, with Toth pencils and Colletta inks.

Chronologically, the precursor of Jack doing layouts might have been as early as 1963. Up until that time, most of the new super-hero line was pure Kirby/Lee, but by the cover date of March 1963, there is only one book, Fantastic Four, with Kirby art produced. On that month, all the other titles drawn by Kirby up until then are handed over to the other resident artists. The Hulk went to Ditko, Strange Tales went to Ayers (which made sense since he was probably even more experienced at drawing Torch stories than Kirby). Journey Into Mystery tried out with Al Hartley (but settled better with Joe Sinnott), and Don Heck jumped in with both feet, premiering his super-hero drawing abilities with Ant-Man in Astonish and a new feature called Iron Man in Suspense (actually, Iron Man was to premiere earlier, but that’s another story). This was the first attempt to have others continue the Kirby/Lee technique, but many of the stories showed the lack of something (or someone). Of course while this was going on, Jack was not idle; he was behind the scenes drawing and developing, in conjunction with Stan, what would become The Avengers, The X-Men, Sgt. Fury, FF Annual #1 and Strange Tales Annual #2. Up front he continued to draw the monthly FF adventures, a Thor, Iron Man, Ant-Man, or Torch story here and there, and the cover art for almost the complete line.

When Sgt. Fury, The Avengers, and The X-Men premiere, the process begins to repeat itself. Kirby draws approximately the first year of stories and then another artist comes in to continue; but unlike the earlier non-Kirby period, Jack doesn’t leave entirely. We now finally come to 1965; there are more titles to draw than ever before, and unlike two years previous, Stan cannot resort to his resident artists to fill in because they already have their hands full drawing books. Enter the freelancers; some were old friends of Stan from the Timely/Atlas days, some were from competitor companies, some were talented newcomers; but none were experienced at drawing stories “Marvel method.” It is during this time and for this reason that Jack is persuaded to do layouts to help these “new” artists.

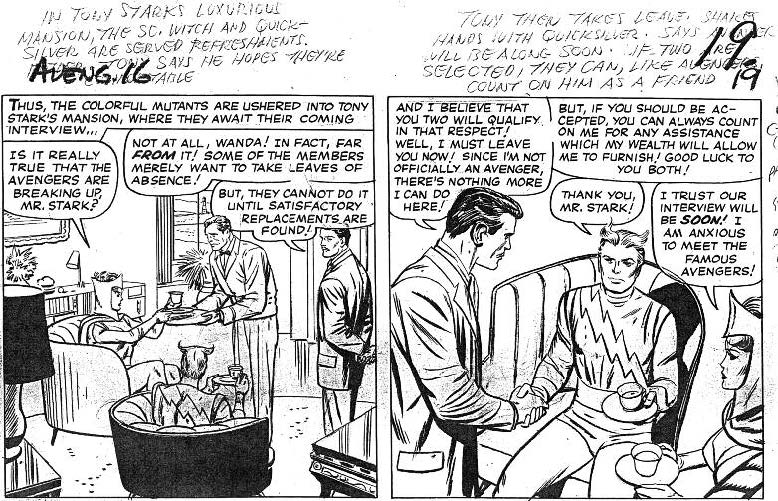

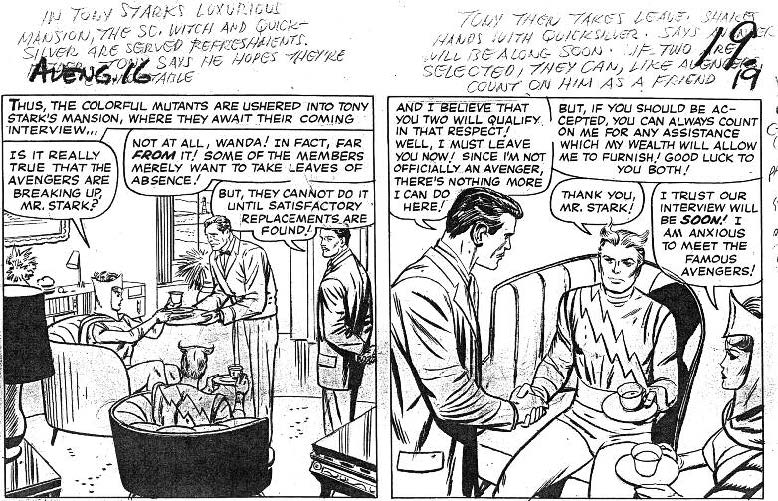

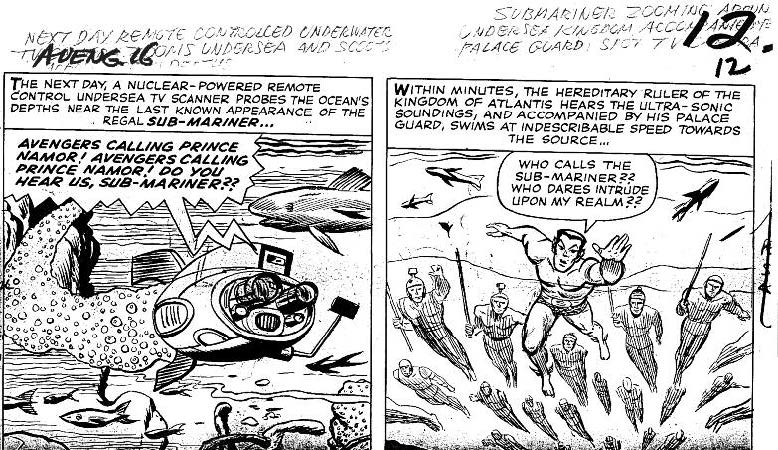

Jack is first credited with layouts in Avengers #14 (cover-dated March 1965), but of course this should not infer that Jack didn’t influence plots or artwork for other artists prior to this. There is an excellent article in the Jack Kirby Quarterly by Nigel Kitching which covers Kirby contributing art “help” on stories where his name doesn’t appear, like Avengers #9-13. On copies of the original art to Avengers #14 there is evidence of Jack’s border notes similar to the type we covered on the Journey into Mystery #111 article in TJKC #26, but this particular issue seemed to have many hands in it; Lee, Ivey, Heck, Stone, et. al. Jack also lays out the stories to Avengers #15 and #16, by which time his border notes become much more expansive and descriptive. These three issues appear to be Jack’s “dry run” at leaving pencil and story layouts for other artists to follow.

Jack’s notes here show the involvement he had in helping determine the personalities and motivations of the characters.

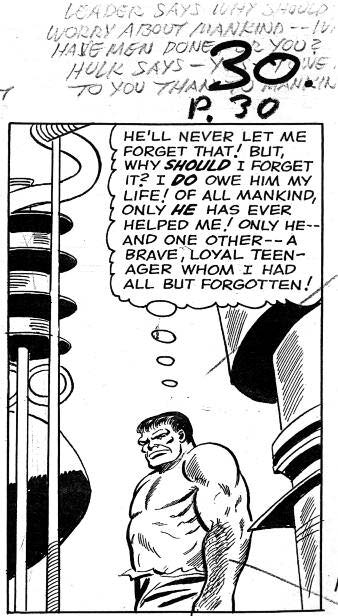

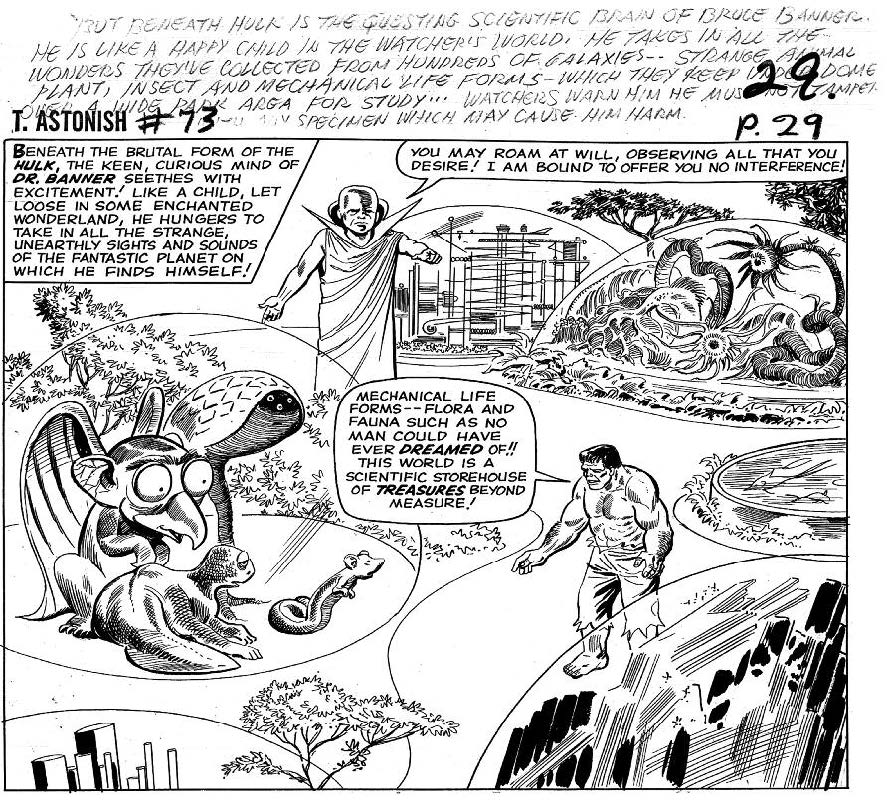

By May/June 1965 Jack has finished with layouts on The Avengers and with penciling on The X-Men (issue #11 was his last as artist), but he has picked up “The Hulk” in Tales to Astonish (#68). Up until that time, Steve Ditko was drawing and co-plotting the stories. Mark Evanier related to me that it was Ditko who originally pitched the idea of giving The Hulk a series to Lee; perhaps it was Lee who suggested putting The Hulk in the Goblin story in Spider-Man #14 (cover-dated July 1964) that alerted Ditko that the character was being shuffled around looking for a home. Ditko therefore made the suggestion which led to The Hulk series beginning in Astonish #60 (cover-dated October 1964, after Lee and Dick Ayers indoctrinated Astonish readers to The Hulk in Astonish #59). After leaving the Hulk series, the very next month in Spider-Man, Ditko begins receiving a (long-delayed) co-plotting credit (he doesn’t receive co-plotting credit on “Dr. Strange” until two months later); coincidence? Ditko’s problems with Marvel were growing—but back to Jack.

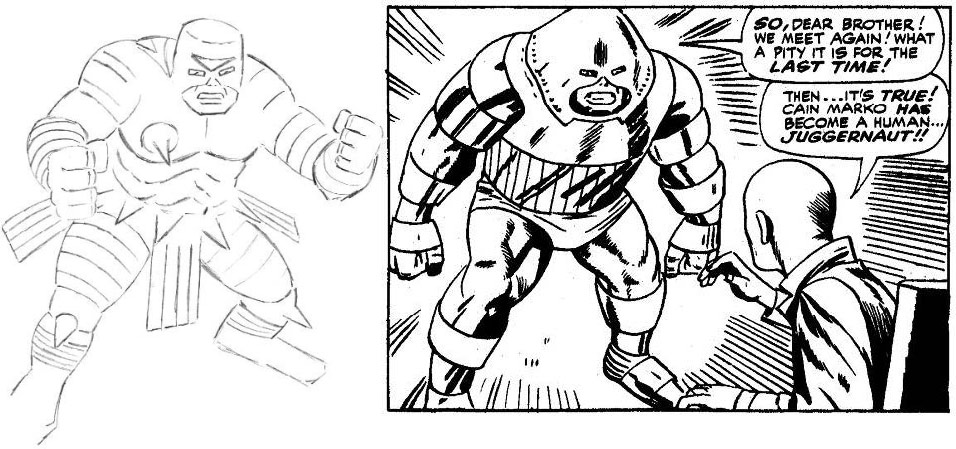

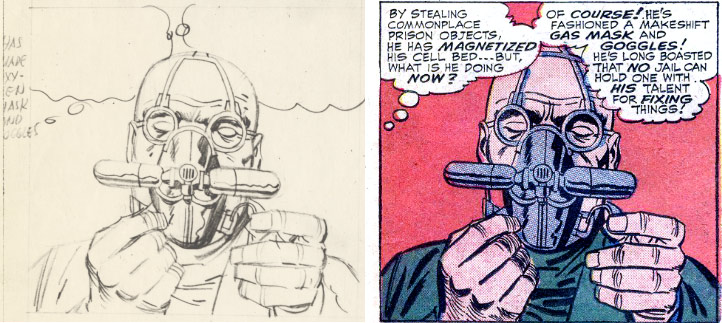

Mike Gartland’s lightboxed version of Kirby’s original design for the Juggernaut, which was still visible in blue pencil under a pasted-up stat of the final panel of X-Men #12 (right). Since Jack didn’t tend to use blue pencil, this suggests that Alex Toth also worked on the original Juggernaut figure.

Between June and August 1965, Jack co-plots and draws the Hulk stories for Astonish #68-70 and begins doing layouts—similar to the Avengers stories—for The X-Men; he also adds plot and pencils to help Stan launch the new “Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” series in Strange Tales. With The X-Men, Jack leaves layouts and border notes for Alex Toth, in what may have been his “try-out” issue. This is not to say that Toth was new to the field; he was an accomplished draftsman long before this, but working “Marvel method” may not have been his cup of tea. He leaves after only one issue, a shame really. By the way, this particular issue (X-Men #12) is of interest not only for the obvious introduction of The Juggernaut; on the originals Kirby layed-out, The Juggernaut was originally intended to look different, with a flat helmet (à la the Atlas Black Knight), a waist apron similar to Galactus’, and spikes on the breastplate. Obviously someone thought him a little too lethal (or ridiculous) looking and asked for changes. Also it is my opinion that in keeping with the ‘Origin of Professor X’ storyline, Jack intended for Cain Marko (The Juggernaut) to be the cause of Professor X becoming crippled. Although I’ve yet to verify this through the original art, the powerful images on pages 12 and 13 seem to confirm this, and the fact that Jack probably came up with the name Cain Marko (“the mark of Cain”) would fit into the brother vs. brother plot. Stan almost always used alliterative names on characters he was writing. Stan of course would have had to change the “Marko cripples Professor X” plot since he knew he had previously established this in an earlier issue of X-Men (#9) using the villain Lucifer. In reviewing the border notes to the originals from X-Men #9 it is apparent that the crippling of Xavier at Lucifer’s hands was not part of the original plot; there are no border notes by Jack pertaining to the incident, and the notes in the borders by Lee pertaining to it are written over erased Kirby notes. Also there is evidence of Wite-Out correction on word balloons in which the incident is added. So it would seem as though Lee added the crippling plot after the story was handed in, which is why Jack probably didn’t know about it, or remember it if Lee informed him of it; which makes me wonder how much collaboration Kirby and Lee were doing on The X-Men to begin with. (And for those who want to point out that Xavier appears later on walking with Marko in the Korean flashback, you’ll notice by examining the art that there is no evidence that the other soldier was meant to be Xavier in the first place.) Enough with the tangents, back to the story.

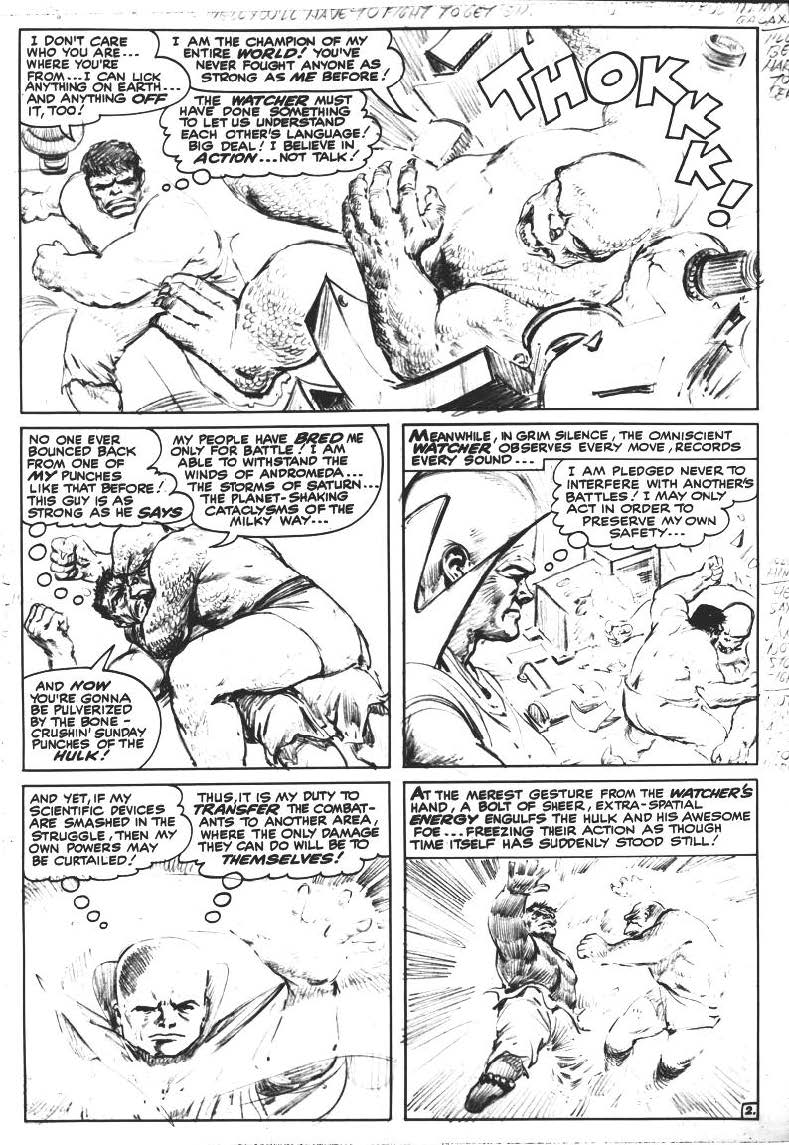

Original art from Tales of Suspense #72. As plotlines got more involved, Kirby began leaving longer, almost paragraph-length notes with his layouts.

It is on the books cover-dated September 1965 that Jack is firmly established as layout artist. Jack begins in tandem plotting and leaving pencil layouts for Strange Tales, Astonish, X-Men, and Suspense (Jack was co-plotting and drawing the Captain America series in Suspense up until that point). He is also co-plotting and doing pencils for Thor and FF, plus cover art for the line. On examples of original art, Jack’s border notes begin to become almost paragraph-length, leaving detailed descriptions and brief dialogue for the resident artist. Jack (and maybe even Stan) wasn’t sure who would be drawing what story at any given month, so these notes were not directed at any of the artists’ abilities. Seasoned veterans to Marvel, like Ayers and Heck, probably only referred to them for the plot or occasional panel dynamics. It was the “new guys” coming in that all of these layouts were for.

With each title Jack was laying out, Stan tried introducing one of the “new” guys as artist. That was, after all, part of the whole idea behind bringing Jack in on this project. Plots were worked out between Kirby and Lee, Jack would then flesh out the story with varying degrees of pencil work, accompanying the pencils with border directions. The artist would follow this lead, in Stan’s hope that he would add his own technique and flair to the finished art. Lee would then add dialogue and captions and make any last-minute editorial changes. This time period in Marvel marks the beginning of the artistic second wave; we’ll take them one at a time.

After Alex Toth left X-Men, Werner Roth, an old friend of Stan’s from the Atlas days (1950-57) came back under the pseudonym Jay Gavin. Moonlighting from his romance work at DC, Roth adapted readily and within six months was working “Marvel method” with Roy Thomas as the regular artist on the title and stayed with it for almost two years. Kirby is credited with layouts on issues #12-17, although it is possible that he stayed on in one capacity or another until Roy came on in issue #20. From the onset, Jack was more devoted to this title than the others he helped launch at the same time and didn’t seem to leave it creatively until another writer came on. Two of the X-Men’s most memorable foes, The Juggernaut and The Sentinels, were created by Jack during this period.

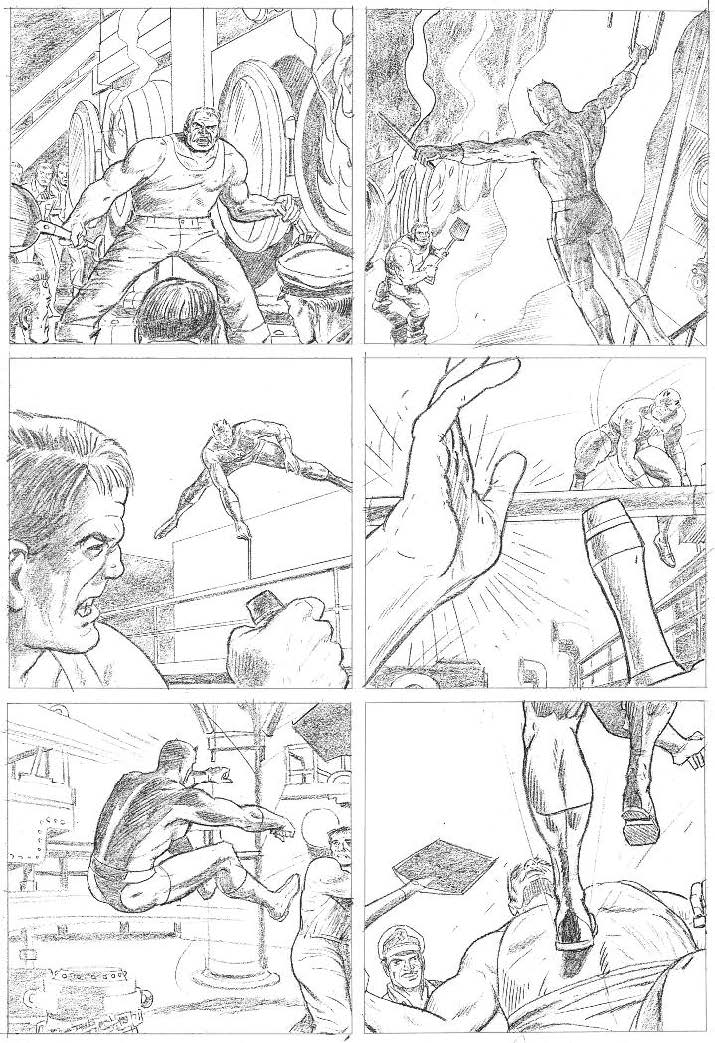

As stated previously, Jack came in on “The Hulk” in Tales To Astonish #68; after drawing the first three chapters he begins doing layouts for Mickey Demeo. Demeo is one of the more recognized pseudonyms in Marvel mythos; the artist’s real name is even more recognized throughout all of comicdom: Mike Esposito. Esposito is one-half of the legendary team of Andru & Esposito, as recognized and loved as Simon & Kirby to many. As with many from DC at that time, Mike took a false name (the Demeo was his then-wife’s maiden name). According to Esposito, Jack’s layouts looked like rough sketches and you had to pull them together as best you could. Sometimes the Kirby layout pencils were defined enough that Mike could draw over them in ink (as opposed to penciling over the layout, then inking it). This may help to explain why, in so many of the stories in the various titles layed-out by Jack, the Kirby look comes through even over another artist’s work. Jack almost always did more defined pencils on the splash and would occasionally pencil a panel here or there. Esposito stays on to pencil a few issues, alternating with Bob Powell, but then opts to ink rather than pencil. In the interim, Gil Kane sneaks in for his first try at “Marvel method,” penciling one story under the pen-name of Scott Edwards. John Romita also comes in for one issue, then “The Hulk” settles down with Bill Everett until issue #84 when he and Jack leave the series. Jack actually was credited with layouts up until issue #83, but #84 credits many Marvel hands so it’s possible he was in on it. Jack stayed with this title for 17 issues; there was only one other title in which he would stay on longer as layout artist. It happened to be the new kid on the block.

In addition to layouts for other pencilers, Jack provided tighter pencils for Giacoia to ink in Strange Tales #141.

Anyone from my generation knows about the James Bond series of the Sixties and the plethora of spin-offs that it gave birth to. Stan, ever commercial, ever topical, naturally jumped onto this bandwagon. He and Jack came up with “Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.”; this series showcased all of the crazy high-tech gadgetry and far-out scientific concepts that made the secret agent genre popular and Jack was already known for. Stan also resolved the problem of bringing Sgt. Fury into the current Marvel timeline by making him the secret agent in the series (Jack and Stan lightly touched on a present-day Fury in the pages of FF #21, as an operative of the C.I.A., but this brought him back in ernest as a regular Marvel character). Jack penciled the first story in Strange Tales #135 (Aug. ’65), but as with the Hulk series in Astonish, he stops doing full pencils and begins doing layouts with the issue cover-dated Sept. ’65. And with this new title would come another “new” artist.

Bob Powell’s uninked pencils over Kirby layouts for Tales To Astonish #74, from stats in Jack’s files. Marvel sent these to help Jack maintain continuity between issues—which shows how directly involved he was with the plotting.

John Severin was hardly “new” to the medium, well known for his work with EC, Harvey Kurtzman, Mad, and especially Cracked magazine; his association with Marvel dated, like Roth, from the Fifties when he did mostly westerns for Stan. Although his work showed promise, like Esposito, he didn’t stay long as penciler. After three issues Severin was gone; he ironically goes back in time with Fury, ending up inking Dick Ayers’ pencils on the Sgt. Fury book. After Severin leaves, the “S.H.I.E.L.D.” book becomes a virtual revolving door of interim pencilers; it appeared that whoever was free for an assignment or wanted to try out was given a shot. Sinnott, Giacoia, Esposito, Purcell, and even Ogden Whitney of Skyman/ACG fame pitched in for an installment. The dependable Don Heck did a few issues; and John Buscema came back to Marvel in the pages of a “S.H.I.E.L.D.” book. Buscema was also one of Stan’s “friends of the Fifties” group; Buscema likes to relate the story of how, when given the Kirby layouts to the story, he erased them all and drew the book his way. John’s words from The Art of John Buscema: “It was ‘Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.’, and I didn’t pencil it. Jack Kirby broke it down. That’s how much confidence Stan had in me. He had Jack Kirby break it down, and I penciled it over, and repenciled the whole thing. I erased every panel and redrew it, because I couldn’t draw like Kirby… and it came out pathetic.” As has been noted on other occasions, Stan never wanted his other artists to draw like Kirby, but to learn his abilities at dynamic storytelling, which is probably why with the border notes/directions, Jack was requested to do the pencil layouts. After Buscema, with issue #151, “S.H.I.E.L.D.” finally settles down with an artist who not only stays with it, and is a newcomer, but happens to be perfect for the book.

One of Dick Ayers’ Daredevil tryout pages, before John Romita got the strip, working over Kirby layouts.

Jim Steranko cut his comic art teeth at Harvey, but found fame at Marvel. Like Kirby, his art had a cinematic technique, and more importantly, he executed the “pop art/psychedelic”” style into his then-current work, blending perfectly with the secret agent “camp” look; unlike Kirby, his style was sleek and polished, which also contributed to a better look for this particular series. Steranko would become the definitive artist for “Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D,” and even though his total work for Marvel would end up being less than thirty issues, it was a testament to his talent that it would be enough to ensure his fame. What is also of interest is that, within three months of his first story, by Strange Tales #154, Steranko begins being credited as writer of the series, making him the first regular artist/writer at Marvel. As with X-Men, it appears that Kirby stays with this title until a new regular writer takes over, and as with X-Men, Stan relinquishes the “writing” credit and only edits the book thereafter. Jack does layouts on “Nick Fury” for 18 months, longer than any other series in which he is credited as layout artist; and seeing as how there seemed to be no regular artist on the series until the arrival of Steranko, it is to Jack’s credit that he was able to maintain story quality throughout.

Kirby was often called upon to make art corrections on other artists’ work. Don Heck’s original Cap figure is visible under this one, presumably redrawn by Kirby for this Tales of Suspense #58 panel.

Since Jack only did layouts on two issues of Daredevil, some would say why even bring it up? There’s an interesting story behind it; Daredevil was, up until that time, in the creative hands of Wally Wood, who made the character more dynamic, visually stunning, and marketable than he ever was previously. Wood was, however, slated to begin work on the new “Sub- Mariner” series debuting in Astonish #70, which is probably why the character last appeared in Daredevil (#7). The Daredevil book was being handled by Wood associate Bob Powell, who was preserving the Wood “look.” In the interim, however, Wood had a huge disagreement with Lee and refused to do any more stories (note: although Daredevil #10 is cover-dated Oct. ’65—two months after Astonish #70—since it was a bi-monthly, it was possible that it was drawn around the same time). By the cover date of Dec. ’65, Wood was gone, and Powell with him. Stan was initially going to bring in Dick Ayers to take over the book, but really didn’t want to take Dick away from his other drawing assignments; as Dick was preparing some pages for the Daredevil book (of which he still has a few), enter John Romita. Romita had just returned to Marvel, having known Stan from the “Timely” days; previous to his return he was grinding out romance work for DC. Stan immediately gave John the Daredevil assignment, but unlike Ayers, John was not used to working Marvel method, so… enter Jack Kirby. Jack layed-out issues #12-13, and by #14 Romita was well on his way, staying on the title until issue #19 when he leaves in order to take over the artistic seat in Spider-Man.

With the “Captain America” series in Tales of Suspense, Jack follows the same program. He was the resident co-plotter and artist from its inception in issue #59 (cover-dated Nov. ’64), until issue #69 when he begins doing layouts. Issue #69 is cover-dated Sept. ’65, just as was Astonish #71 and Strange Tales #136; was this more than just coincidence? (And just as with the Hulk story in Astonish #59, Stan introduces Suspense readers to Cap in a pre-series story in Suspense #58, drawn by Heck, with Kirby art corrections interspersed.) The “new” artist for this series was the indomitable George Tuska. Tuska was well known throughout the industry, drawing every genre imaginable for every known comic book publisher; always on the move, he rarely stayed with any one company exclusively. After issue #69, which was handled by Ayers, Tuska comes in as artist and does his usual yeomanly work for five issues, then he’s on the move again, leaving Marvel for Tower. After another fill-in by dependable Dick Ayers, the series brings in John Romita for two issues, then goes back to Jack doing full pencils by issue #78. Jack stays with the series, co-plotting and penciling until issue #86, then leaves for five issues (Suspense #86 is cover-dated Feb. ’67, the same time he left Strange Tales at #153). Why he left is unclear, but by Feb. ’67, Jack was definitely done with doing layouts.

In addition to Jack’s margin notes, notice how Cyclops’ hand was repositioned in the published version of this panel from X-Men #12. Good call!

For two years Jack did layout work for Marvel; for completists, the breakdown went something like this:

- March 1965-May 1965: Avengers #14, #15, & #16

- July 1965-March 1966: X-Men #12-17

- September 1965-May 1966: Tales of Suspense (Captain America) #69-77

- September 1965-September 1966: Tales to Astonish (Hulk) #71-83

- September 1965-February 1967: Strange Tales (Nick Fury) #136-153

- January 1966-February 1966: Daredevil #12 & #13

And these represent only credited layouts; it’s very possible that Jack had story input on one or two issues after he left, until the writer following him either picked up his thread or established his own. With only two exceptions—Avengers #16 and Suspense #77—Jack leaves all of his last layed-out stories open for the writer and artist following to conclude. Even the two exceptions are hardly that, since Avengers #16 leaves the plot thread of the search for The Hulk which is in the following issue (and which also vaguely ties in with the Hulk story in Astonish #69 using Kirby paste-ups), and the Suspense (Cap) storyline is continued by Kirby himself with issue #78. If the aforementioned stories give the appearance of my giving credit to Kirby as writer, it is only in the non-conventional sense, as it is my opinion that the plots and stories at this point were coming from Jack. These layed-out stories coincide with the same period of time when Jack was developing the interwoven plotlines in FF and Thor, along with the introduction of new characters and concepts there. Jack begins doing layouts in ernest at about the same time as the continuing stories of FF #38-up and Thor #116-up are running. The border notes on all of Jack’s stories become more involved and detailed at this point, indicating that he is leaving more direction and being left more on his own than in the earlier years. Stan was there, to be sure, with plot input, editorial corrections, dialogue, and captions. Stan was credited as “writer,” but at this point he was leaving no written synopsis, plot, or script for Jack to follow. Most of the time there were story conferences, and Stan likes to relate how he would only have to give “the germ of an idea” to his collaborator and send him off; with Kirby he once mentioned that even this wasn’t necessary. “Sometimes Jack would tell me what the next story would be,” he once opined. He also referred to Jack as a “conceptualizer,” which, by definition, implies the act of forming notions, ideas, or concepts; and even the ones not originated by Jack were being passed through him for input if time permitted. With this in view it is my opinion that, although they probably worked more closely in the earlier years, with the expansion of the line occupying more of Lee’s time and the previously mentioned changes in how the stories were being done, the majority of the plots and stories on the books Kirby was involved in were probably coming from Jack. In discussing this topic with several of the artists working on the layout books, more than one mentioned that Jack’s border notes were being left for the writer of the dialogue, not the artist. Stan, in an unpublished interview, stated that he couldn’t understand how Jack could say that he (Jack) was doing the writing; well, there are many examples of Jack’s border notes being used by Lee for both dialogue and descriptive purposes (and of course, there are examples of Lee disregarding said notes, sometimes to much better effect). So if co-plotting, dialogue, and captions make Stan the “writer,” I’d have to add that, since Jack co-plotted, broke down, drew (or layed-out), and left writing directions, that made him the “storyteller”; something Jack liked to refer to himself as anyway.

More of Jack’s margin notes, this time from X-Men #14. Kirby layouts, Werner Roth finishes, Colletta inks.

As time went on, Jack was becoming more and more dissatisfied with doing layouts for Marvel. It was mentioned in earlier articles how during this ’65-’67 period, Jack noticed that Stan was getting the lion’s share of the publicity and recognition for all of the characters and concepts that they originally developed together. Others, such as Ditko and Wood, also voiced their dislike of the fact that now, thanks to the “Marvel method,” the artist may have more creative freedom with the stories (to the extent of sometimes doing them virtually solo), but they weren’t receiving any sort of writing credit. The artist would do 75% of the work, but only be paid the standard page rate for penciling; Lee, on the other hand, would be paid for writing, editing, and dialoguing a story Already fleshed out and drawn. This is not to say that Lee didn’t earn his pay, but the “Marvel method” proved that the stories were at the least co-written where people like Kirby, Ditko, and Wood were concerned; but credit arguments concerning Stan are hardly a new topic.

Detail from Avengers #16. Jack may have done tighter layouts here, as much of his style shows through Ayers’ finishes.

Aside from credits, one topic which Stan strongly supported was a better pay rate for the people working with him. This is where many have come to realize that Martin Goodman was more involved with the new Marvel than had been previously mentioned. One of the main reasons that so many of the artists and inkers that came to Marvel in the mid-Sixties didn’t stay long was because of the terrible pay rates. Although Marvel was becoming financially successful after decades of stagnation, Goodman would not put more money into the comic book division of his holdings; only after the cajoling and sometimes begging of Lee would Goodman relent. He also was eternally pessimistic concerning concepts, often telling Stan to cancel books before the first sales figures would come in (as he did with Hulk and Spider-Man); if not for Stan, they would never have gotten off the ground and their popularity realized. Goodman was also ambivalent about talent. It didn’t bother him if an artist quit; to him they were replaceable commodities. Stan knew where the talent was and must have become increasingly discouraged to not have the financial backing to lure them away. Artists who would come to Marvel during this layout period were offered as much as 30 dollars a page, provided that they penciled and inked it; some were offered less. Joe Sinnott relates the story of how, when he inked the historic FF #5, he was paid seven dollars a page for inks; had he been paid more he may have stayed on and the history of comic art might have been changed. Marvel was notorious for having among the lowest rates in the business, and Goodman tried his best to keep them that way (good business savvy, but terrible on morale).

Jack, of course, received a better rate as a penciler, but never as much as he was promised or felt he deserved. The layout work he did just added insult to injury, as Jack was only paid 25% of his usual page rate; near the end it may have been moved up to around a third, but he still felt it was terrible pay. He felt that he was receiving one fourth of the money for what he considered the important three fourths of the penciler’s job. And as with FF and Thor during this period, it also increased the number of comics per month where Jack was contributing story ideas and plots to comics that were published with sole writer credit going to Lee. Jack announced several times that he didn’t want to do layouts any longer, but was persuaded to do a few more, to help out artists who were new to the “Marvel method” of doing comics; and then a few more and a few more until he finally issued an ultimatum that he would not do any more. This is probably why, although the layout work begins at virtually the same time, it doesn’t end abruptly, but rather peters out. Within eight months of the last story Jack lays out, he comes to the conclusion that he’s given enough ideas to “The House of Ideas,” and because of a failure to communicate, rides out the wave until something better comes along—but the secession of creativity is anti-climactic, as it becomes apparent over the years that what he’s left them is enough to sustain them for decades; and he is yet to receive his proper recognition in the company by the company… shame!

(We’d like to thank Dick Ayers, Mike Esposito, Mark Evanier, Richard Howell, John Romita, Joe Sinnott, Clem So, Chic Stone, and George Tuska for supplying information pertinent to the writing of this article.)

Fantastic in depth article. It really benefits by being augmented by the addition artwork.

One thing I’d like to see people get away from is accepting Lee’s version of the Marvel Method. As related to the layouts it’s always been obvious to me Lee wanted Kirby doing layouts not because of Kirby’s artwork, but because he wanted Kirby writing more books and creating more characters. Rand has a number of layout stats at the Kirby Museum and a look at them shows that they were almost stick figures in many cases. They certainly aren’t close to what is usually thought of as layouts. Layouts are what John Buscema gave to Alfredo Alcalla.

Here is one example of a Kirby “layout”

//kirbymuseum.org/gallery2/d/22985-2/Tales_of_Suspense_70-9_Layout.jpg

Pingback: Follow Up to Mike Gartland’s “The Best Laid (Out) Plans” | The Kirby Effect

I’m not sure the best way to describe this complex division of labor. Perhaps Spider-man did it best (Stan Lee: Script and editing/Steve Ditko: Plot and art). Or perhaps it was more like Jim Starlin’s early work as artist/writer: Jim Starlin: everything except (your name here) additional dialogue. It seems that the truth is somewhere between these two extremes with Stan and Jack. We will never know beyond a doubt,

What a fantastic article. The more this we get, the more clearly the case can be made that Jack not only created but was greatly responsible for so many stories.

Keep up the good work!