Previous – 1. Jack Kirby’s America | Contents | Next – 3. Escape To New York

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

A WORLD DIVIDED

When the Great War ended, the socio-political landscape had been turned on its head. And from the resulting chaos, the world split into two ever-conflicting political spheres, two ideological philosophies at odds with each other. Democracy vs. the isms; one side led by free people, and freely elected leaders, and democratic principles, the other by the philosophical dictators of Fascism, Communism, Nazism, and Militarism. The ensuing chaos would lead to financial meltdown.

The horror of the Wall St. Crash of Oct. 1929 had quickly filtered down to the bottom of the food chain. Jobs that were once rare and low paying became even rarer and lower paying. Quarters and fifty cent pieces used for pulps, and juvenile series books became scarce, the financial meltdown wiped out whole groups of children’s entertainment. The slick magazines vanished—too expensive. This soon became the age of the radio, a free source of hour upon hour of storytelling and escape. The Lone Ranger, the Green Hornet, even strips like Superman soon expanded into the radio waves. Kids would lay endlessly next to the large wooden box listening to endless comedians, adventure stories and the latest jazz tunes.

So strong was the radio as a source that a Halloween scary tale put the nation on high alert. In 1938, Orson Wells presented the sci-fi play The War of the Worlds, based on an H. G. Wells book on a syndicated radio program. Set up in a realistic news-flash manner, people began to believe the play as reality and began flooding the police and military about this strange attack by an alien force. The outrage and impact lasted for days until the other media quieted the mobs down.

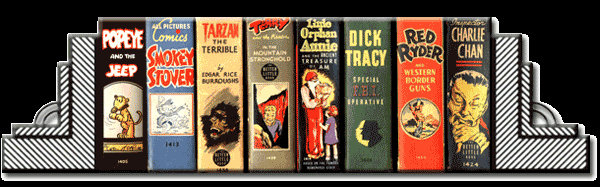

Interestingly, a new format magazine moved in to fill the void. A small sized amalgam of newspaper comic strip and text story. Published by Whitman Publications and called Big Little Books, these strange pocket-sized books presented popular newspaper funnies like Dick Tracy and Flash Gordon, as well as radio characters like the Lone Ranger, and Disney characters like Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse in long form, hard covered stand alone stories. Although there were numerous variations in outside dimensions and in number of pages, most were 3 5/8″ x 4 1/2″ x 1 1/2″ in size and 432 pages in length. For the most part, the writer and illustrator were anonymous worker drones. The outstanding feature of the books was the captioned picture opposite each page of text. The books originally sold for a dime (later 15¢).

Typical spot illustration (from Tailspin Tommy) They weren’t above T&A

The Big Little Book® was created in 1932 when Sam Lowe conceived of a special book that would be bulky but small so that it could be easily handled and read by a young consumer. He made up three samples using cover and paper stock that would be used in the printing. He had the Art Department do black and white drawings and insert keyline text so that the dummy samples could serve as prototypes. Taking the prototypes to New York, he presented them as a ten-cent retail item, packed one dozen per title in a shipping carton. Retail buyers were intrigued with the concept and were particularly impressed with the titles. Lowe returned to Racine with more than 25,000 books pre-ordered.

Many children learned to read and have an appreciation for illustrated books because of their experiences with BLBs. The poor printing, cheap paper, and small size allowed for the cheapest priced reading material directly for children. In many instances, these small books were the first time these characters were directed to the specific children’s market in a retail format. It didn’t go unnoticed.

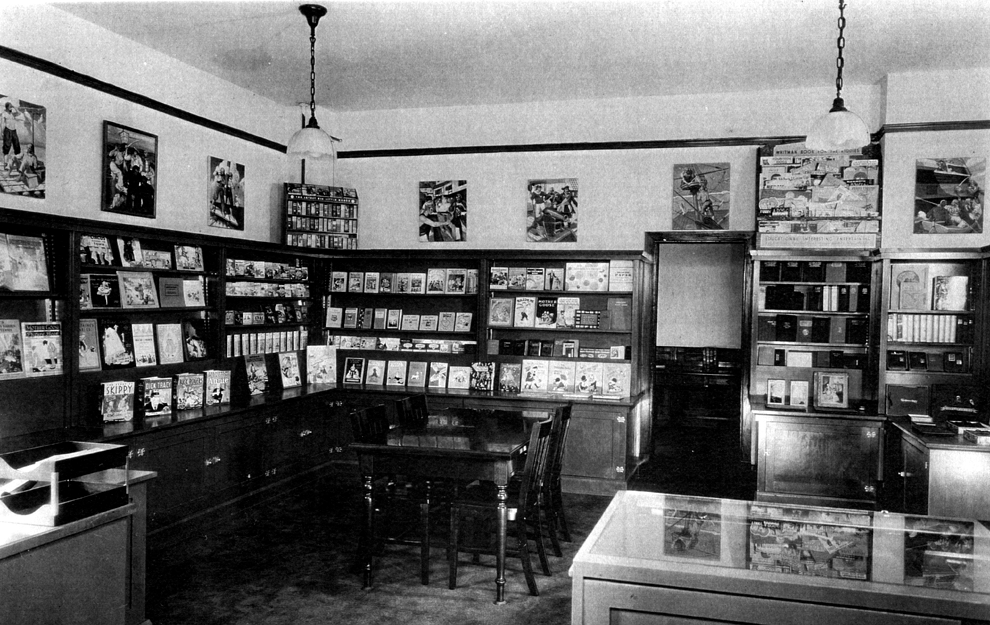

New York retail display room Imagine this much room for a .10 cent item

In mid-1938, Whitman changed its logo from Big Little Book® to Better Little Book®, marking the start of the Second Age (mid-1938-1950) in which the books slowly faded away due to economic and societal changes and the stiff competition from comic books. Not surprisingly, the 1938 date matches up with the appearance of Superman and the super-hero phenomenon; one format giving way to the new.

Still in the grasp of the Great Depression, it gave rise to a wealth of fresh Americana based upon inexpensive forms of entertainment. Ten-cent motion pictures, cheap reading materials like BLB’s and comics, and free-radio programs came from a few of the industries that prospered during the decade, and their influence was felt deeply and is remembered warmly by millions of people. It was truly a Golden Age for films, radio programs, and inexpensive reading materials.

Colorful, small and lots of drawings

Jake’s life was also caught in great schisms; old country vs. new, tall vs. short, Haves vs. have-nots, schmoes vs. swells, Jews vs. Gentiles, gangsters and straights. Nothing scarred the youngster’s psyche so much as watching his father struggle to keep the family sheltered and clothed, or watching his mother losing her spark of joy, growing old before her time. The thrill of becoming a Bar Mitzvah would give way to a stark realization that his childhood had come to an end. The stickball games after school, and the long summers soaring over the rooftops, exploring the streets and playing cops and robbers till dark, were over. Jake was no longer a child, the innocent idylls of youth, once taken for granted, gave way to a new truth; he had to take his place as a source of family income.

But being poor wasn’t a death sentence—it could also be an inspiration. Jimmy Cagney put it this way: “Though we were poor, we didn’t know we were poor. We realized we didn’t get three squares on the table every day, and there was no such thing as a good second suit, but we had no objective knowledge that we were poor. We just went from day to day doing the best we could, hoping to get through the really rough periods with a minimum of hunger and want. We simply didn’t have time to realize we were poor, although we did realize the desperation of life around us.” Sometimes life is too immediate to step back and see just how bad it was.

During the height of the Depression, family survival was tantamount and any added income was an important plus. Jake’s time spent drawing and reading was time not spent helping out with the family budget. Jake had no interest in being a tailor, so joining his dad at work, or moonlighting after hours was out of the question. After school, and on the weekends, he managed odd jobs, such as being a gofer for the reporters at the Daily News, drawing bags for shopkeepers and sign-making, but most often he hawked newspapers. Kirby recalls, perhaps apocryphally, “I enrolled at Pratt Institute. When I arrived home after the first day of classes, I discovered my father had lost his job. I was out of Pratt and selling newspapers the next day.” Due to his small stature, when Jacob found honest work to make a few pennies, he ran face first into urban Darwinism. Kirby recounts; “When I’d go to pick up the papers off the truck at the building, I’d be the little kid that got trampled.” Newsboys had a distinct pecking order, with the larger, stronger boys commanding the choicest locations, and largest bundles. Any intrusions into these prime locations were met with immediate and painful consequences. Being a “newsie” was also a gateway to petty crime as the boys would often add pick pocketing and other methods to up their daily take, and then lose it to craps, pitching pennies, or other small ante gambling games. Every newsie spoke of William Lipshitz in revered tones. The newsie turned hitman was just one of the many gangsters that the young hoods idolized. Jews had the same dreams we had. John Garfield would half-joke “If I hadn’t become an actor, I might have become Public Enemy Number One.” Jewish-American organized crime arose among slum kids who in pre-puberty stole from pushcarts, who as adolescents extorted money from store owners,– until as adults they joined well organized gangs, led by luminaries such as Moe Annenberg or Meyer Lansky, and became involved in a wide variety of criminal enterprises boosted by prohibition. The lure of quick money, power and the romance of the criminal lifestyle was as attractive to the second-generation Jewish immigrants as it was to the Irish and the Italians. It didn’t hurt that Meyer Lansky, the big cheese was only a little over 5 ft. tall. Something a short person could dream of– a democratic pursuit.

Newsies at work and play

The soul-robbing endless cycle of poverty, juvenile delinquency, and crime hung over Jake’s Lower East Side like a mourning shroud. The Jewish enclave was tight and offered a sanctuary of commonality for the older family members steeped in the Old World folklore and traditions, but to the children of the urban street who went to public schools with Irish, Italians, Poles, and Blacks, these old country ways offered no guidance.

Kirby told historian Greg Theakston; “I couldn’t accept the poverty. I couldn’t accept my parents in such poor circumstances either. I was a Depression child, and I couldn’t accept the things that were going on around me.” Yet despair is a curious thing, it can break the will, or it can forge a determination that can rise above it. Kirby recalls that life in the ghetto, “gave me a fierce drive to get out of it. It made me so fearful of it, that in an immature way, I fantasized a dream world more realistic than the reality around me.” Jack lived in the Lower East Side, there was no guarantee that he would ever get out; many didn’t. They say a man is the culmination of the choices he makes. The Lower East Side offered many choices for the young man, some good, but an awful lot bad; the easy lure of the con man, the romanticism of the gangster, the easy life of the gambler looked pretty nice compared to the menial factory job, or the drudgery of the assembly line. But Rose and Ben had raised Jacob right, he knew right from wrong and to avoid the detours found in the ghetto. The problem was how to see the straight and narrow with all the roadblocks the slums put in one’s path. Jack understood the realities such as Yedda Goldstein lying face down on a concrete surface rather than burn in her work building, or Louis Cohen- shot down like a rabid animal for crossing the wrong person, or Julius Rosenberg writhing in the electric chair for making just such wrong choices. Jack also knew of Lillian Wald, or Mickey Marcus, Bernard Baruch or Jimmy Cagney and knew there was a path out that didn’t include lying, violence, or scamming. He needed a map.

By 1932, Jacob had to make a decision. He was 15 edging on 16, and the scrapping was taking a nasty turn towards real consequences. Broken bones, incarceration, even death was now a constant companion. A close friend was shot in the neck, while another friend’s Mom jumped to her death from a building top. The rats were not just those hated, furry little rodents, now they were the strong arm bullies taking hard earned movie money, the enemy gangs, the petty hoods, the slum lords and dishonest cops intruding on Jacobs’ turf, and he was helpless to do anything about it. Jake’s parents were good people, but in this new world, they were as lost as Jacob. How could they show him a path out of the ghetto, which they couldn’t find? His father was now 45, and already an old man. The ten to twelve hour shifts, often six days a week, hunched over a sewing machine, in a dimly lit, smoke filled, windowless factory, had left Ben physically and spiritually bent and broken. He had little energy or quality time to give Jake the help and guidance the child needed. In the absence of an adult role model, peer pressure becomes the guiding factor, and the macho posing necessary to survive on the streets can deprive the child of the skills, and desire needed to succeed in the outside world. Education became a waste of time, time better spent in shooting craps, petty crime, or fighting. Reading or drawing? That’s sissy stuff; no real man would be caught dead wasting his time with that. Honest work? It’s a scam, guaranteed to break your spirit and your back. Hustling was quicker, cleaner, and you wore better clothes, if you could get away with it. Jacob had choices; most of them were not very good.

Jakie saw through the petty gangsters. “They weren’t the heroes. The gangsters were just guys who wanted the $400 suits, and they wanted it now. I didn’t care what I wore. They were guys who wanted money fast, and they paid for it.” Gangster Mickey Cohen a local strongarm/bodyguard described the feeling; “I started rooting – you know, sticking up joints – with some older guys. By now I had gotten a taste of what the racket world really was – the glamour, the way they dressed, the way they always had a pocketful of money.” “I got a kick out of having a big bankroll in my pocket. Even if I only made a couple hundred dollars, I’d always keep it in fives and tens so it’d look big.” Jack was lucky, others, such as the well known Louis Cohen were not so lucky. Louis was born Louis Kerzner near Jack’s Suffolk St home. Running the streets pick pocketing and other petty crimes led the youth to meeting up with Jacob “Augie” Orgen a bigger time Jewish mobster, known for his anti-union activities. Louis walked the streets like a god; a role model for all the street hustlers and newsies to admire and emulate. Louis Cohen was a dreamer — he wanted to be a gangster and win respect from the people, and wear those $400 suits. The Little Augie gangsters played on his ambition until he did the dirty work they were loath to tackle. Eager to please, the young hood was hired by Louis Buchalter and Legs Diamond to kill noted rival Nathan Kaplan- another anti-unionist. A gang war between the rival factions broke out resulting in a particularly violent fight on Essex St –in which several innocents were shot. Cohen shot Kaplan in front of the Essex County Court House, and was immediately arrested—he was not a particularly bright young man. Orgen became sole operator of the labor busting rackets. After exiting prison Cohen agreed to finger Buchalter. Along with buddy Isadore Friedman he had made an arrangement with feisty prosecutor Thomas Dewey. Buchalter found out through informants within the states attorney’s office and shot and killed both Cohen and Friedman like dogs on the street; their bodies for all to see as an object lesson in the Lower East Side. Louis Cohen never fulfilled his dream. Such was the education of Jacob Kurtzberg. Historian Michael Sugarman observes with wry humor; “You have to look at the irony of the situation. The immigrants wanted their children to lead a successful, law-abiding life, and live the “American Dream”. Now the irony was, in the time of the Depression and Prohibition, when organized crime flourished, you couldn’t be both successful and law abiding, in most cases. The only real successful people were the gangsters. The law-abiding ones were dirt poor. This is said mostly in jest; truth be told there were many positive influences o the young boy. They were just outnumbered by the relentless presence of the mobster class.

To be fair, the area had its heroes. Lillian D. Wald was born of a German Jewish family in Cincinnati, Ohio. She graduated from the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses and then took courses at the Woman’s Medical College. Spurred on by a close friend, she adopted the Lower East Side and decided the area needed nursing care. Wald’s work, along with her partner Mary Brewster, in the area prompted her to move there to be a visiting nurse and help aid the families who were living in horrible conditions. After gaining a sponsor, Wald’s practice grew as did her staff, which by 1913 had grown to 92 people She worked in the area for forty years. Her practice became the Henry Street Settlement and then turned into the Visiting Nurse Service of New York City. The Settlement expanded its range of services to meet the needs of the local community. This included nursing, the establishment of clubs, a savings bank, a library and vocational training for young people. By 1903 Wald was organizing 18 district nursing service centers that overall treated 4,500 patients in New York. Wald early resolved that the Henry Street nurses would be nonsectarian and would charge fees only to those who could pay. There would be no religious or racial discrimination for their services.

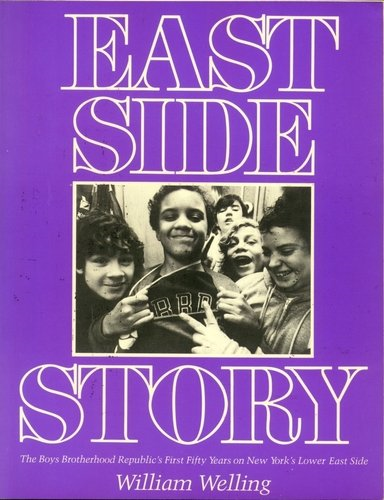

Over the next few years Wald promoted the idea of building public playgrounds and cultural institutions in working class areas. In 1915, Wald founded the Neighborhood Playhouse on Grand St. to serve as a cultural center and later an acting school. After the war, she expanded into many social concerns. She helped her friend Margaret Sanger, she marched for the right to vote, and she led the fight against the horrible child labor conditions. She fought for medical staff inside the educational buildings. She helped start the NAACP. Her work for civil rights stands as a landmark of tolerance. A confirmed trade Unionist and pacifist. The Henry St. Settlement has become a treasured landmark in the Lower East Side. To this day it continues the fight against disease, poverty, and oppression. The Boys Brotherhood Republic was swallowed up by the Henry Settlement Complex and they share spaces at 888 East 6th Street, It remains one of the cultural centers of the LES. Her work was the perfect compliment to Harry Slonaker and the BBR.

Mickey Marcus was born on Hester St, not far from Jake’s block. Being athletic and bright he earned his way in to West Point. After graduation he returned to New York became a lawyer and won appointments to several prestigious jobs with the D.A. Most importantly, he led the prosecution of Lucky Luciano. He was speculated to become the first Jewish Mayor of New York. But first came World War 2. Mickey reenlisted and was made part of Eisenhower’s brain trust. Marcus helped draw up the surrender terms for Italy and Germany and became part of the occupation government in Berlin after 1945. During that time, Marcus was placed in charge of planning how to sustain the starving millions in areas liberated by the Allies, and clearing out the Nazi concentration camps. After the war he returned to New York where he was approached by the new Israeli Defense Dept and asked to set up a new army; first to win separation from Great Britain and then to keep it from the Arab countries. It was during these early years in Israel that Marcus was killed by friendly fire while touring an encampment. He was returned to New York and buried with honors from two countries. There were heroes, just not as glamorous as the lowlifes.

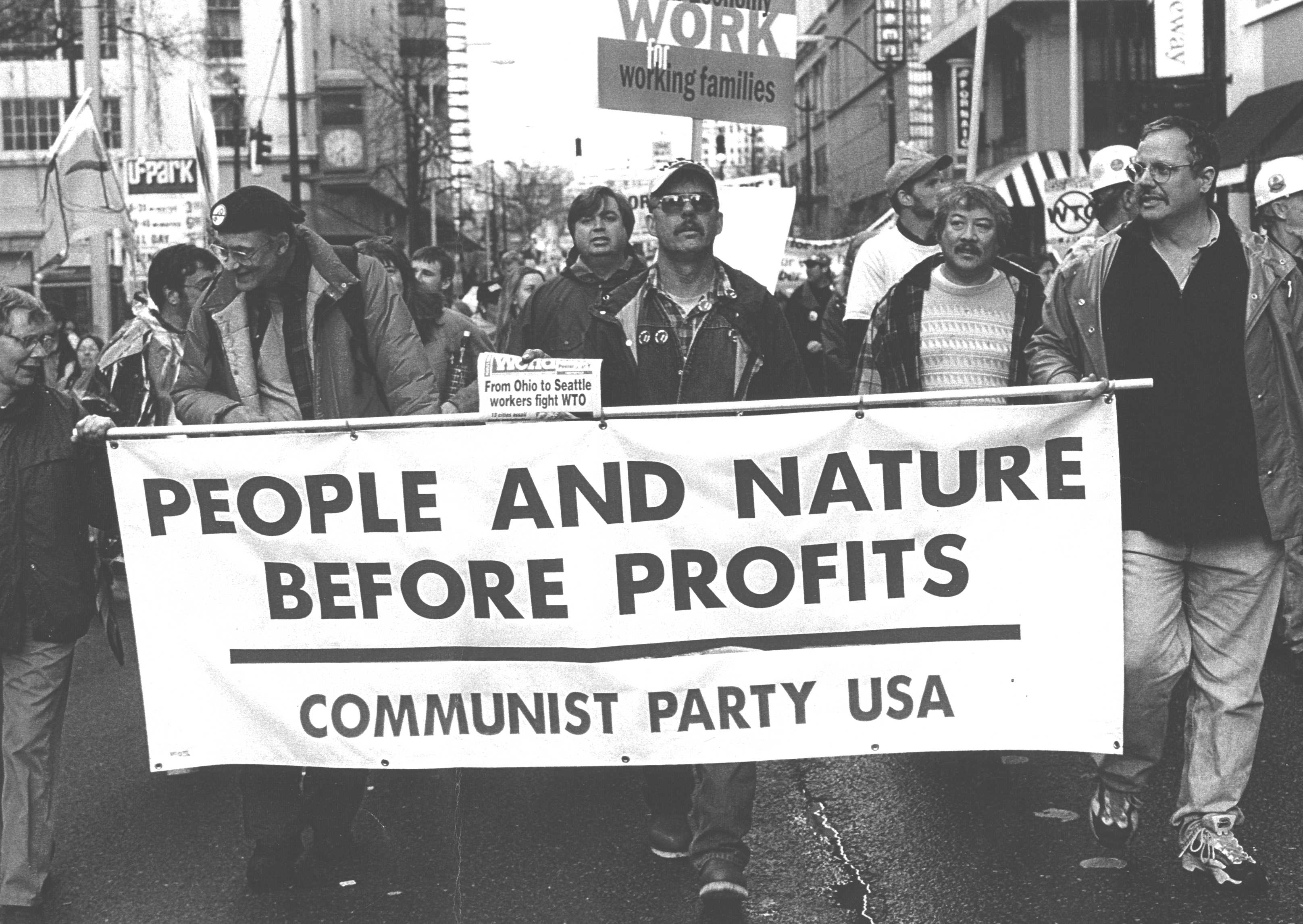

Running the streets with Morris Cohen or Georgie Comet, Chubby Clee, and the Klinghoffer boys—Albie and Leon, was exciting and energetic, but going nowhere. It all just seemed like dead ends. Some became gangsters, some street hoods and some youths took their anger and frustrations to the streets, joining the anarchists like the Young Communist League who marched and pushed for worker’s rights and social reform. It’s been said that upwards of 12,000 kids were active members of the Commie Bunds in New York by 1939—ever watching the progress being made by the new government in Mother Russia. One such bomb thrower was a neighbor of Jacob Kurtzberg named Julius Rosenberg.

In March, 1931, 9 black youths were arrested after a gang type melee in Scottsboro, Alabama.; some younger than Jacob. 2 white women falsely accused them of raping them. White hysteria erupts and the demand is made to lynch them. The local sheriff puts a stop to the mob, but promised a swift trial. Two weeks later, after a kangaroo court –where their appointed lawyer refused to put up a defense, they were sentenced to die. The prosecuting attorney makes it plain. “Guilty or not, let’s kill these niggers.” The legal arm of the Communist party, the ILD, (perhaps for its own reasons) takes up their case and whips up support from up north. The world soon takes notice. On June 27th upwards of 5000 people both black and white march in protest in Harlem, New York. Among those fellow Communists marching was a first time protester, Julius Rosenberg. After many later trials, several of the boys are freed, and the others faced reduced sentences.

The only paper to come to their aid

His passion for the radical has been ignited. The intertwining of socialism and civil rights was an important ingredient in the rise of both. The black population had no better ally than the equally downtrodden Jewish people. The freedom riders—those northern youths sent south to help blacks vote were a combination of idealistic blacks and Jewish kids– and their fates were often the same.

The Daily Worker had grown into a passable newspaper after some early problems. Though usually a fixture of Soviet propaganda it did find a place in America among the class conscious workers. Dick Briefer-of Frankenstein Comics fame had a regular strip called Pinky Rankin for several years. Surprisingly their baseball coverage was among the best around. It was from this perch that the demand for mixed ball emerged. It is doubtful that baseball would become integrated without the constant haranguing of the Daily Worker.

On Sunday, August 16, 1936, under the headline, “Fans Ask End of Jim Crow Baseball,” the Sunday Worker pronounced “Jim Crow baseball must end.” Thus began the Communist Party newspaper’s campaign to end discrimination in the national pastime. The story, written by sports editor Lester Rodney, questioned the fairness of segregated baseball. Rodney believed that black ballplayers from the Negro Leagues would improve the quality of play in the major leagues. He appealed to readers to demand that the national pastime — particularly team owners, or “magnates” as the newspaper called them — admit black ballplayers. “Fans, it’s up to you! Tell the big league magnates that you’re sick of the poor pitching in the American League.” “Big league ball is on the downgrade, “Rodney declared, “You pay the high prices. Demand better ball. Demand Americanism in baseball, equal opportunities for Negro and white stars.”

It’s an interesting mix, politics, sports, and civil rights.

Ida M Van Etten wrote of the American/Russian Jewish dilemma, their allegiance both to America and their hold from Mother Russia, and the fear of established political parties.

“ Politically, the Jews possess many characteristics of the best citizens. Their respect and desire for education make them most unlikely to follow an ignorant demagogue, while for a still deeper and more radical reason they make an enlightened selfishness their standard of all political worth. The centuries during which every conscious and unconscious tendency of the governments under which they lived has been to make their individual and race advancement their single object, have developed traits of character most unfavorable to that blind partisanship which is requisite for the successful carrying out of the objects of political organizations like Tammany Hall. The education given by the modern labor movement has, in a great degree, transformed their race-feeling into a class-feeling, and they now look with zeal to the advancement of the working people, in whole elevation they recognize that their hope for the future lies. The one or two Jewish political demagogues who strive to create a following on the East Side have met with doubtful success. In fact, there does not exist a more unpromising field in New York for the political trickster than the Jewish quarter of the city. Their cold, critical analysis of political nostrums is most disheartening to the district-leaders of Tammany Hall. Unlike most native or Irish voters, they are proof against the blandishments of the campaign orator and the fascinations of the torchlight procession and brass band. The great mass of Russian Jews are not yet naturalized, but of those who are, the vast majority voted last year with the Socialist Labor party. “

By the early 1900’s several socialist representatives won their seats for the Lower East Side. Jack looked with amazement on the local Tammany Hall pols shoving money at the great unwashed for votes; looked like a job for a young man on the move. “The average politician was crooked. That was my ambition, to be a crooked politician” Jack laughed.

Such was the quandary Jacob found himself; ill-equipped to make it in the outside world, yet too small, too smart, and too sensitive to want to join the world of gangsters, petty crime, or the anarchists. Jake needed a mentor, someone who could help him bridge the gulf that divided his squalid world of limited hope, from a universe of endless possibilities. A positive role model who was every bit the equal to the constant negative reinforcement shoved down a young boys’ throat.

Hard times and gangsters wearing nice suits

How Harry Slonaker, and the Boys Brotherhood Republic happened to be in New York’s Lower East Side at this time, has become the stuff of folklore. Comedian Jerry Stiller, an early member told BusinessWeek magazine in an interview from the Dec. 12, 2003 issue, “The BBR started when some kids in the neighborhood were caught playing dice on the street and were arrested. They were going to be shipped off to reform school when a social worker from Chicago named Harry Slonaker, who had seen what happened, pleaded with the judge. “Give them to me,” he said.”

Harry Slonaker remembered it differently; one day, while walking around the tough neighborhoods of New York’s Lower East Side, Harry happened on a group of kids shooting craps in an alleyway. He approached the kids, with an offer, “I’ll fade you”. The wary kids, suspecting a copper, grabbed their meager cash and the bones and started to run from this man in an overcoat. “Naw, don’t beat it!” Harry pleaded. “Come on, let’s shoot some dice, I’ll fade you”, he pleaded. The boys reluctantly returned, and as the game progressed, he offered forth an idea. “What do you say we form a club?” Despite numerous objections from the boys, that “clubs are sissy stuff”, Harry finally won some of the kids over, and they formed the BBR.

Harry’s reminiscence is accurate, just not complete, for Harry wasn’t just happening by the Lower East Side; he was actually on a mission. Harry Edward Slonaker was not a native New Yorker; he was born on Nov.17th, 1903, in Hammond, Indiana, the only child of James and Bernice Slonaker. Hammond is a small town in the upper Northwest quadrant of the state, just across the border from Illinois. At some period, during his childhood, Harry’s family crossed that border and settled in Chicago. This was the Chicago of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, bloody race riots, drive by shootings, and Al Capone.

In 1914, a Chicago salesman named Jack Robbins ventured into a Chicago courthouse where 7 boys were being sentenced for petty larceny. Robbins spoke up on behalf of the boys, and the court sentenced them to probation under his control. (Interesting how this legend jumps from founder to founder) After talking with the boys, all ex-members of various organized boy’s clubs, Robbins came to the conclusion that they had failed because the clubs had been organized and run totally by grown-ups, and the kids rebelled due to lack of any real responsibility and say. His solution became the Boys Brotherhood Republic.

“Where Boy’s Rule” was not just the club’s motto, it was its raison d’être. The BBR functioned like a self-contained political entity. The boys, from 14 to 18 would elect their own Mayor, and City Council, and other departments. The boys paid taxes and were required to put in time in their chosen committees. There was also training and tutoring in sports, art, and vocational areas. On one wall hung a plaque bearing the words “We are digging a well, where other boys may drink”; a constant reminder that what was learned and lived at BBR must continue to the next generation. The success was astounding, boys petitioned to join by the dozens.

On front of home building

Jack Robbins was thinking about expanding his philosophy to New York City. On Feb. 23, 1931, in the Lower East Side, he held a public meeting attended by over a hundred kids, and several local dignitaries to gauge local support for the club. When asked how soon the kids would like to have a BBR, the answer was a resounding “TOMORROW!”

With this affirmative call to action, Jack Robbins explained his plan to the boys. “It is important that the supervisor of the New York Boys Brotherhood Republic should be an adult who is either a former BBR citizen from Chicago, or who has received substantial training in Chicago.” “This man is to be in sympathy with self-governing ideas, and is to have an understanding of the desires of the elements of the boys to be under his supervision.”

In early Jan, 1932, Harry Slonaker, the former mayor of the NW Chicago BBR set up shop, and hit the NY streets looking for recruits. He started with a small group of kids rolling dice, and by the end of January, a core group was formed and the first meeting of the Boys Brotherhood Republic in NYC was held.

Harry Slonaker by Alfred Eisenstatz

Jacob Kurtzberg joined a couple months later, probably at the urging of Georgie Comet or Chubby Clee, who were among the first to join the group. In fact, Chubby was the first elected Mayor of the Group. The next several years, the BBR would offer him an alternative to the gangs, the rats, and the hopelessness that shrouded his future. At the BBR, he found like-minded friends also looking to improve their lives. The BBR was an island of tranquility amidst the chaos and tumult of his Lower East Side existence. The BBR art club gave him a place where his artistic skills were appreciated, rather than the subject of cruel taunting, and his talents were put to productive use.

“The boys publish and mimeograph a weekly newspaper which sells for one cent. Harry Slonaker never sees it until after it is printed. There is a camera club and art club, which likewise run themselves. If a boy is interested in drawing he joins the club and the other boys take a hand and teach them what they have learned. The professional appearance of their posters speak well for their ability”

Off the Straight and Narrow

Caroline Bayard Colgate 1937

Perhaps even more important, the BBR instilled in him the discipline and work ethic that hopelessness robbed of so many. Jacob didn’t need Harry Slonaker to know right from wrong, his parents had taught him that, but he needed a mentor like Harry Slonaker to show how he could overcome the negative shackles of a street education that taught that doing the right thing was a fool’s game. Jack Kirby recalls; “It was a country that kids ran, this organization that Harry started. He thought that if he gave kids responsibility it would give them hope, and there was so little hope then.”. “We learned responsibility. For the first time it was in our own hands, and we learned how to deal with it.”

Jerry Stiller recalls; “BBR really helped you find something within yourself. It was a place where we found a connection with each other. We were children of immigrants: Irish, Italian, Polish, Jewish, Chinese, black, and Hispanic. There was no ethnic divide. It was so beautifully connected. There was no prejudice or bigotry.”

Sol Kassen remembers the early days;

“We were so anxious, sometimes we arrived early and would have to wait outside the doors until Harry Slonaker opened up. He would sit upstairs by the window until 4 p.m. sharp, when he’d let in these boys — who now say they otherwise might have stolen, vandalized or cheated for a good time had it not been for the club. It was just so cold that day. Kasson couldn’t wait. “Aw c’mon, Harry, why don’t you let us go in a little earlier? “ To get some attention Kasson picked up a rock and threw it at a window. He didn’t mean to, but he shattered the glass. Out came Slonaker. ”

“Before they started this club we used to steal and get into all kinds of trouble,” said Sol Gelber, the kids of the east side were very poor. We didn`t have anything and we couldn`t feel any hope. The club really changed our lives. It`s like our motto, `when there are boys in trouble we too are in trouble.”

”I think that club was more than fun. It gave a sense of what is good and right,” Hank Walzer, said. “We never lost touch. We went to one another’s bar mitzvahs and weddings. It was like one big family.”

“It was a great time for me,” Jack would claim. “I made lots of friends.” Ralph Hittman, who would go on to lead the BBR recalls Jacob as “a quiet guy.” “Played ball like everyone else, but was usually drawing comic strips.” Hittman recalls an activity called Fighting for Fun where Jake was boxing another boy name Milt Cherry, and Jake lost. “Jake looked pugnacious but he really wasn’t.” Not surprisingly, Jack would tell of a boxing match where one of the boys taunted him, really going after Kirby’s short stature. Jack’s temper reached a boil and as the bell sounded, he threw himself across the ring and the fight was quickly ended with a one punch knockout by the small battler.

Jacob became an integral part of the BBR’s self-published newspaper, providing editorial comment, and original art that accompanied the issues. His K’s Konceptions,–small gag comments– cranked out from a crude mimeograph, were the first published artwork of his now legendary career.

The citizens of the BBR took their responsibilities seriously; the in-house court was a busy place. Missed meetings, returning books late, and major offenses like fighting or gambling would get a member brought before the court. In 1935 they even held an impeachment trial for one of the Judges. George Comet, one of Jake’s closest friends, was the prosecuting attorney, and Jake was the court reporter and court artist. The highlight of the account in the BBR Reporter was Jake’s spot illustrations, and his terse little remarks on the witnesses. Former BBR Judge Morris Kosatzky’s attempt to foist himself off as an authority on BBR laws became “a much disputed fact by both attornies.” “Hercules” Hershberg, who sat in a “spread eagle position”, while answering questions was “the funniest witness ever to occupy a chair.” In response to one question he declared; “Awright so I’ll answer yes or no. Who wants to beat around the bush?” Councilman Spinner “wore a sinister smirk” while Councilman Rosen was taking copious notes because “he couldn’t weigh the evidence in his cranium,” but mostly, he and everyone “were very attentive and devouring every piece of evidence.”

Jake could wax serious too. In a BBR Reporter article he compares the early Reporter with the new version. “Today, The Reporter is one of the greatest BBR institutions. The press room is a scene of buzzing activity. The camera staff is always at work, and experimenting on some new process of turning out pictures for the newspaper. The editor can always be noticed bawling out the art staff plus firing a reporter here and there. The mimeograph squad; with sleeves rolled up and reeking with sweat, turn out page after page. At important events, the BBR Reporter is always represented in the ever present Press Box. Like the BBR itself, the BBR Reporter has risen from a thing of insignificance, to a thing filled with activity, and pulsating with life.”

The English isn’t perfect, the syntax slightly shattered, but Jack’s unique facility with the written word was evident early. Among his friends on the BBR staff was Albie Klinghoffer, who doubled as the BBR Reporter’s Business manager, and cameraman. His brother Leon would become infamous when in 1985 he was murdered on the cruise ship Achille Lauro by Palestinian terrorists. Supposedly the wheelchair bound Klinghoffer spat in the face of one of the terrorists. Consequently, he was shot and dumped overboard.

Nothing was more important or more time-consuming for Harry Slonaker then his relentless push to help his kids find gainful employment. The members would plaster walls and bridges with posters and placards seeking work. They would send personal letters to business owners pleading for summer job applicants. Many of the BBR youths left to take jobs with President Roosevelt’s new CCC program.

Kirby credits the time spent at the BBR, for giving him the means to escape the slums. “I drew caricatures of other club members, made jokes about the things they did. The others loved it. I drew other things like titles, and other cartoons. I even wrote a couple articles. It was a good experience for me. It’s what finally got me out of the neighborhood and into a real job.” Kirby explained. “Harry Slonaker, who I felt was like my own father, was responsible for making me a decent human being. We came out responsible adults.”

Learn more from their book

Harry Slonaker and the BBR allowed Jacob Kurtzberg to find his dignity and self-worth, and just like the club newspaper, Jacob had “risen from a thing of insignificance, to a thing filled with activity, and pulsating with life.” The boy became a man. This dreamer wouldn’t end up a corpse on the street.

Previous – 1. Jack Kirby’s America | top | Next – 3. Escape To New York

Pingback: Looking For The Awesome – 3. Escape To New York | The Kirby Effect