Previous – Preface | Contents | Next – 2. A World Divided

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

JACK KIRBY’S AMERICA

“Winters got real severe and a lot of people passed away. I remember having a lot of sweaters on me. I can tell you. Our idea of preventing disease was to wear four or five sweaters and everything else you could put on.” So what did people depend on? “God. My mother held much faith in God and on folklore. She was also a great storyteller. I got that talent from her and by listening to her every night. The best stories are the ones that can touch you; anytime anyone tells you a good story and it is in person they have a smell, a sound, and they breathe. That is the essence of good storytelling, when it can reach out and touch you. My mother learned storytelling from her mother. Like her mother and her mother’s mother, my mother told me tales about people, God and the land they lived on. That’s the kind of home I grew up in.” Jack swallowed hard after talking about his mother. To his mother, he was always Jacov.

It is not a coincidence that Shalom Aleichem the great Hebrew story writer; called by some the Jewish Mark Twain – though Twain would always claim that he was the American Shalom Aleichem – spent the last years of his illustrious life living and dying in poverty among the Jewish cast-offs in the Lower East Side. After escaping Czarist Russia due to a pogrom, he wearily made his way to New York. He died fitfully spitting out his life among the thousands of Tuberculosis victims suffering there. These people lived Shalom’s stories, they were Shalom’s stories, and they loved their lost homelands. Shalom Aleichem died just as Jacob came into the world. One generation always gave way to the next. Perhaps it was Shalom’s talents that found a new vessel in Jacob’s hands.

They were the stories of a people, a people displaced by nature, and resettled in hell. But they survived, and they passed on their collective knowledge, and their stories never end, they just keep adding new chapters.

Mulberry St. Lower East Side 1920

August 28, 1917, for 4 years Europe had been engulfed in a horrific war—“the War to end all wars”. The United States had joined the bloody conflict four months earlier, and by June, the first Yanks landed in Europe, making this truly a World War. Thousands of miles away, in a stifling cold water flat located in the bowels of New York City, Benjamin and Rose Kurtzberg delivered their first child. Ben had recently emigrated from Austria, where the stench of persecution, war and poverty had been a constant. By the conclusion of this unparalleled cataclysm, an ancient era had passed. Gone were the Czars, Archdukes, and Kaisers, left powerless were Kings and Emperors, whose legacy of absolute authority had stretched for centuries. The age of the feudal lieges, lording over personal fiefdoms had ended. Jacob Kurtzberg, was truly born from the death throes of these Old Gods. Europe’s era had ended.

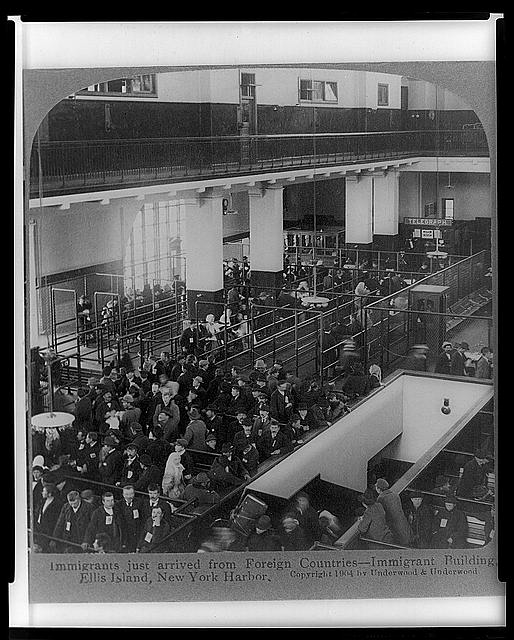

Ben and Rose were part of the massive Jewish tide that overwhelmed the United States at the turn of the Century. Jack’s romanticized story was that his father escaped Austria in 1907 in order to avoid a duel-of-honor with a German aristocrat. Yeah well, Jack told stories. Landing at Ellis Island, Ben found refuge in America’s Calcutta, New York’s Lower East Side. Ben’s family was from a section of Austria-Hungary known as Galicia. Beginning in the 1880s, a mass emigration of the Galician populace occurred. Caused by an horrible economic condition, and a growing Jewish animosity. Rural poverty was widespread; the emigration began in the western, Polish populated part of Galicia and quickly shifted east to the Ukrainian inhabited Eastern parts. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans all participated in this mass movement of countryfolk and villagers. Poles migrated principally to New England and the midwestern states of the United States. Jews mostly emigrated directly to New York and Chicago. A total of several hundred thousand people were involved in this Great Economic Emigration which grew steadily more intense until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Immigrants in cattle pens at Ellis Island

Rose’s family had come to America from Russia a few years earlier, possibly to escape the great Kishinev pogroms of 1903-5. Czarist Russia was becoming more and more inhospitable to the Jewish population, even those residing inside the Pale of Settlement.

The New York Times reported: 4.28.1903

“The anti-Jewish riots in Kishinev are worse than the censor will permit to publish. There was a well laid-out plan for the general massacre of Jews on the day following the Russian Easter. The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, “Kill the Jews,” was taken up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep; The dead number 120 and the injured about 500. The scenes of horror attending this massacre are beyond description. Babes were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied and bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded. Those who could make their escape fled in terror, and the city is now practically deserted of Jews.”

Louis B. Marshal, in his 1904 essay on the 250th Anniversary of Jews in the U.S. wrote;

“In 1880 the number of Jews in the city of New York did not exceed 100,000. Since then, owing to the unspeakable horrors of Russian and Romanian oppression, and of the dire poverty in Galicia and the tide of Jewish immigration has increased in volume year after year, until to-day the Jewish population of New York city amounts to well nigh 750,000, and numbers are constantly increasing.

Many of these new arrivals have not as yet attained the highest standard of citizenship, are still struggling with poverty and misery, are yet unacquainted with our vernacular, and have brought with them unfamiliar customs, strange tongues, and ideas which are the product of centuries of unexampled persecution.

But what of that! They have come to this country with the pious purpose of making it their home; of identifying themselves and their children with its future; of worshipping under its protection, according to their consciences; of becoming its citizens; of loving it; of giving to it their energies, their intelligence, their persistent industry.

The Pilgrim Fathers did no more than this. The progenitors of the leading families of this country were not otherwise; The lineage of the Russian Jew runs back much further than theirs. He is the descendent of men who were renowned for learning and for intellectual achievements when from the St. Lawrence to the Rio Grande, from Sandy Hook to the Golden Gate, this was a howling wilderness.

dead children from a pogrom

The Russian Jew is rapidly becoming the American Jew, and we shall live to see the time when the present dwellers in the tenements will, through their thrift and innate moral powers, hitherto repressed and benumbed, step into the very forefront of the great army of American citizenship.”

Between 1900 and 1924, another 1.75 million Jews would immigrate to America’s shores, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Before 1900, American Jews amounted to less than 1 percent of America’s total population, by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent. There were more Jews in America by then than there were Episcopalians or Presbyterians.

When they landed at Ellis Island, they were met by the Jewish Aid Society. Landsmanshaften were small groups of individuals; often broken up by their areas of origin. They would help the newcomers make the transition as immigrant as harmless as possible. They would arrange living quarters, help with employment, offer entertainment, education and social interaction between the new arrivals and others of like backgrounds. They provided places of worship, financial assistance, even medical and burial aid when needed. They stressed the need for assimilation as quickly as possible.

Both families had settled in a small but tight knit Austrian-Hungarian Jewish enclave in the Lower East Side. They met while working at a textile mill, and after the appropriate arrangements were made, they eventually married.

The currents of time and events don’t flow smoothly. Society and culture grow in fits and starts. There are eras when tsunamis of influences and change collide and release huge amounts of energy and inspiration. The early 1900’s were just such an epoch. It started slow but by the late teens the wave crashed with such force to wipe everything before it away. Politics, art, music, and cultural changes crashed and fed off each other’s energies. And no where was this more obvious than in New York. This was becoming America’s century, and New York was the loci. New York had become the financial, artistic, fashion, entertainment and communications hub of the world. It was a great world spinning and creating its own gravitational force that drew in every diverse element and influence from the rest of the world. And people by the millions, the lowly immigrant and the high and mighty. And once those elements entered into New York’s fiery cauldron, they were melded and transformed into a new form that became the face of America. New technologies in steel-forging and elevator construction led the way for a new profile for New York; one that stretched hundreds of feet higher than ever seen before. Uptown, The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building cracked the sky. Art Nouveau’s frilliness gave way to Art Deco and Modernism’s angles and geometrics. But this was not Jacob/Jacov’s New York!

Hearst, Pulitzer and Ochs competed for the hearts and minds of New York’s citizenry as their newspapers became the symbols for all that was good and bad in society, and gave rise to a new phrase–yellow journalism. Newspaper comic strips by the likes of Winsor McKay and George Herriman captured the hearts of everyone. Muckrakers like Jacob Riis, and Lilian Wald fought the system to bring equality to the masses. Socialism and Progressive Politics railed against the monolithic power of the Corporate Giants born from the Industrial and technical growth of the late 1800’s, and with it came the call for revolution, civil rights and workers rights.

Women rebelled from the tight structured Victorian fashions and wore looser more casual clothing ala the Gibson girls or even worse, male fashions. The Suffragette Movement grew from a new restless female population forced to work in the factories and raise families torn asunder during the Great War, and with it came a demand for power–political, cultural, and even sexual– never thought possible; culminating in the passing of the 19th Amendment giving women the vote. And it was in New York that the great garment industry would grow–from supplying clothes for slaves, to providing clothing for the masses. And those masses of employees fed into the great demand for workers rights and led the way in Unionism and worker dignity. But this was not Rose’s New York.

The art world had been Eurocentric for several generations, but in the early 1900’s a new generation of American artists and architects and writers arose bringing a new perspective, born of European influences but adapted to America’s baser sensitivities.

Broadway, once the center of European Operettas, and Vaudevillian and Parisian revues gave way to a new amalgam forged by Jewish and Irish immigrants drawing inspiration from roots music and the new idiom of jazz blown in fresh from the South. Victor Herbert gave way to Cohan, Berlin and Gershwin. In 1927, true American Musical Theater was born when two sons of European heritage, Jerome Kerns and Oscar Hammerstein II combined and created a new genre with the creation of Showboat–a musical play as compared to a musical revue, and the first truly integrated show.

European Jews weren’t the only ones fleeing prejudice and ending in New York. For a short period after the Civil War there was a period of increased education and employment of blacks. This led to a growing middle-class population and with it, expectations of a better life. In 1896 this period of enlightenment was crushed with the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling; returning parts of the South to a separate society, and minimizing the rights that had popped up post war. Along with a plague of boll weevils that decimated the Southern agrarian economy the labor market disappeared for the black population.

Blacks headed North to a supposed better life, racism was still a problem, but was more hidden and less brutal than in the South. The Northern states allowed blacks to vote, and education was available, and jobs-especially labor jobs- were much more prevalent in the heavy industrial shops. This migration brought upwards of 7 million blacks to the northern states.

Author Richard Wright (Native Son) wrote of the black immigrant in words that can be seen universally.

“I was leaving the South to fling myself into the unknown . . . I was taking a part of the South to transplant in alien soil, to see if it could grow differently, if it could drink of new and cool rains, bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns and, perhaps, to bloom”

The black folks who fled Jim Crow in record numbers, into New York and parts North, after the Civil War had brought their own influences from Africa and the Caribbean Isles.

In the early 1900’s these sons of slaves had reached a point where they demanded recognition for these influences, and in New York a new movement took root. The Harlem Renaissance burst forth with a fury and energy that shook all cultural endeavors. Writers like Hughes, Thurston and Harrison, artists like Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and Romare Bearden brought their roots and colorful energy and made it American, but mostly it was in the music.

Nowhere was the black influence more apparent than the explosion of jazz upon the canvas of America’s musical life. Birthed in New Orleans, Memphis, and other southern towns, jazz matured when it reached the streets of New York and blended with elegant European Waltzes, Yiddish schmaltz, and the folk music of the immigrant workers. Nowhere was this more prominent than in New York’s nightlife where Cab, Duke and Fats Waller ruled with a strong left hand and a swinging groove. Broadway became captivated with Porgy and Bess.

Even sports seemed to bow to New York as Babe Ruth, the ill-bred son of a Baltimore bar owner, and Lou Gehrig, the gentle son of German immigrants held court in all-white Yankee Stadium, and won adulation and the hearts of children everywhere. No blacks need apply. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that what all the people share is that they were the second generation of people thrown into the horror and poverty of New York City. Immigrant or slave made no difference. There is recognition that the second generation always shows the cream rising to the top. The first generation suffered so the second could achieve and overcome. But this was not Ben’s’ New York.

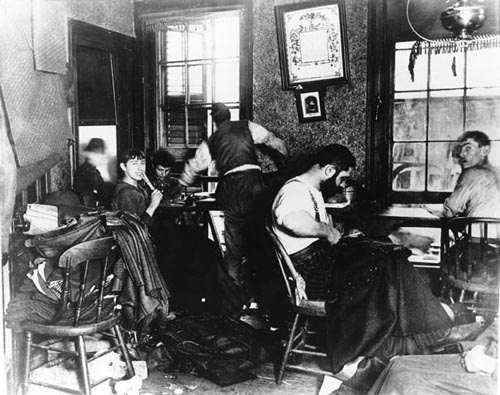

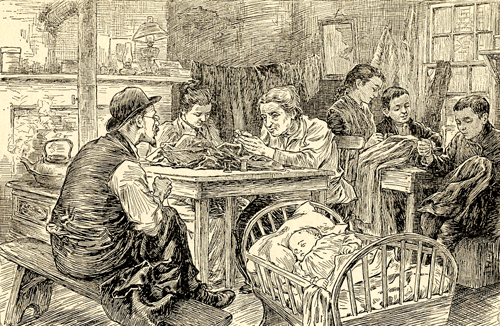

Ben was a first generation immigrant, thrown into the pit of the monster, where a previous generation of Jews from Western Europe looked down on and mistreated the brothers from Eastern Europe. It was a common occurrence that the new immigrants would get the harshest treatment from their own that came earlier. It was the first Irish that beat down and abused the new Irish immigrants who poured off the ships. And it was the earliest Italians who mistreated and impoverished the later Italian immigrants. And it was the first Jews who had opened up the garment shops and manufacturing plants that kept the new Polish/Russian Jews in such poverty. It was an old story freshly told to the new Jews. American Capitalism required fresh blood forced to work for the lowest salary to keep the costs of manufacturing down and increase the competitive edge of North American trade. William Cutting in the movie The Gangs of New York put it most succinctly while observing poor, starving Irish immigrants coming off a ship. “I don’t see Americans; I see trespassers, Irish harps. Do a job for a nickel what a nigger does for a dime and a white man used to get a quarter for.” All while the immoral politician rubs his hand thanking god for new cheap stock for the grist, and unquestioning votes. It was the same moral force that allowed slavery in the South and sweat labor in the North. Slave labor, whether Irish, Italian, black, or Jewish was the energy source that made the factories run. Even after Unionism started to bring higher wages and safer workplaces, Management simply created a new shadow work force. Using a new second level of manager, the owners created what have become known as sweat shops. Independents with a few sewing machines and presses would set up shops in private homes away from the Government regulations and union scale jobs. This second level was known as “sweaters” thus we got sweat shops. This unregulated force paid lower wages, had no time limits, and hired underage workers that made the clothes for a few pennies less that allowed the sweaters to sell their wares to the manufacturers who kept their profit margins and had no overhead—legal or monetary to speak of. They preyed upon the poorest, to whom any work was a blessing, and who had no power; legal, economic or moral to help them out. Workers who had already put in a 12 hour shift came home and worked another couple hours in the comfort of their slum dwellings for even lower wages just to make a few extra pennies to cover expenses. 10, 12, and thirteen year olds worked alongside their parents learning the skills of the seamstress. Roz Goldstein talks of the times she would sit next to her mother learning the art of hand-stitching fine lace, out of need, not curiosity.

The Sweaters of Jewtown copyright Jacob Riis

Jacob Riis talks of this abomination in his book, How The Other Half Lives;

“Many harsh things have been said of the “sweater,” that really apply to the system in which he is a necessary, logical link. It can at least be said of him that he is no worse than the conditions that created him. The sweater is simply the middleman, the sub-contractor, a workman like his fellows, perhaps with the single distinction from the rest that he knows a little English; perhaps not even that, but with the accidental possession of two or three sewing-machines, or of credit enough to hire them, as his capital, who drums up work among the clothing-houses. Of workmen he can always get enough. Every ship-load from German ports brings them to his door in droves, clamoring for work. The sun sets upon the day of the arrival of many a Polish Jew, finding him at work in an East Side tenement, treading the machine and “learning the trade.” Often there are two, sometimes three, sets of sweaters on one job. They work with the rest when they are not drumming up trade, driving their “hands” as they drive their machine, for all they are worth, and making a profit on their work, of course, though in most cases not nearly as extravagant a percentage, probably, as is often supposed. If it resolves itself into a margin of five or six cents, or even less, on a dozen pairs of boys’ trousers, for instance, it is nevertheless enough to make the contractor with his thrifty instincts independent. The workman growls, not at the hard labor or poor pay, but over the pennies another is coining out of his sweat, and on the first opportunity turns sweater himself, and takes his revenge by driving an even closer bargain than his rival tyrant, thus reducing his profits.”

The sweater knows well that the isolation of the workman in his helpless ignorance is his sure foundation, and he has done what he could—with merciless severity where he could—to smother every symptom of awakening intelligence in his slaves. In this effort to perpetuate his despotism he has had the effectual assistance of his own system and the sharp competition that keep the men on starvation wages; of their constitutional greed, that will not permit the sacrifice of temporary advantage, however slight, for permanent good, and above all, of the hungry hordes of immigrants to whom no argument appeals save the cry for bread. Within very recent times he has, however, been forced to partial surrender by the organization of the men to a considerable extent into trades unions, and by experiments in co-operation, under intelligent leadership, that presage the sweater’s doom. But as long as the ignorant crowds continue to come and to herd in these tenements, his grip can never be shaken off. And the supply across the seas is apparently inexhaustible. Every fresh persecution of the Russian or Polish Jew on his native soil starts greater hordes hitherward to confound economical problems, and recruit the sweater’s phalanx. The curse of bigotry and ignorance reaches halfway across the world, to sow its bitter seed in fertile soil in the East Side tenements. If the Jew himself was to blame for the resentment he aroused over there, he is amply punished. He gathers the first-fruits of the harvest here.

It was a simple and logical outreach that led to the creation of freelancing among the artisans and creative work force; a way for the manufacturers to skirt federal regulations. Allowing publishers to have product while keeping the workers as low as possible—and avoiding all the benefits of hiring them as professionals. Turning the laws of Capitalism on its head; more specialized talents should command a higher price. A small need fed by a larger workforce; people with highly specialized talents selling their souls for a mere pittance of its worth, simply because of competition- and hunger. The owners easily pitted one against the other until the lowest possible price, and least bothersome worker was chosen. These artists would gladly sacrifice their law given rights and privileges for the promise of a few pennies to buy food. There was no “work for hire” scheme to be found in the Copyright laws of 1909. It evolved there as a reaction by the owners demanding the copyrights from impoverished artist without the legal or economic power to demand other. With each success by the workers, the owners found new and devious ways to get around it-often using brute force against helpless workers to win their way. It was not for wanting that comic artist never expected to keep their copyrights, or receive reprint benefits, or residuals when their creation was made into toys or advertising faces. It was simple naked power by wealthier owners that told a weaker work force to shut up and be happy with the crumbs thrown their way—or be replaced by even weaker workers. It was this uneven bargaining power that forced Congress to finally improve the Copyright laws in 1976.

“The Enemies of the Working Girl” women and children work late at night while the “working women” – the factory workers fought for better conditions

Yes, America was the new beast, and New York’s uptown was its beating heart. America was now the center of the universe, and Manhattan the blazing sun. But this was not the immigrant’s New York. The Kurtzberg’s New York was the noisy rotting corpse at the center of the hurricane that blew all around; the belching, stinking, fetid energy source that fed the great engine of New York. The Lower East Side of New York at the turn of the century was a crowded, squalid ghetto, teeming with those huddled masses yearning to be free; the lowlies–the hunger dogs– whose blood, sweat, hopes, broken bones, and corpses lubricated the roaring dynamo. The cheap labor source needed to make Capitalism run. This was the Kurtzbergs’ New York.

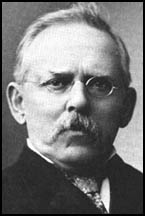

Jacob Riis, from his seminal book, How the Other Half Lives (1890)

“The tenements grow taller, and the gaps in their ranks close up rapidly as we cross the Bowery and, leaving Chinatown and the Italians behind, invade the Hebrew quarter. Baxter Street, with its interminable rows of old clothes shops and its brigades of pullers-in. Bayard Street, with its synagogues and its crowds, gave us a foretaste of it. No need of asking here where we are, the jargon of the street, the signs of the sidewalk, the manner and dress of the people, their unmistakable physiognomy betray their race at every step. Men with queer skull-caps, venerable beard, and the outlandish long-skirted kaftan of the Russian Jew, elbow the ugliest and the handsomest women in the land. The contrast is startling; the old women are hags, the young, houris. Wives and mothers at sixteen, at thirty they are old. So thoroughly has the chosen people crowded out the Gentiles in the Tenth Ward that, when the great Jewish holidays come around every year, the public schools in the district have practically to close up. Of their thousands of pupils, scarcely a handful comes to school. Nor is there any suspicion that the rest are playing hooky. They stay honestly home to celebrate. There is no mistaking it: we are in Jewtown.

Riis

“Here is one seven stories high. The sanitary policeman whose beat this is will tell you that it contains thirty-six families, but the term has a widely different meaning here and on the avenues. In this house, where a case of small-pox was reported, there were fifty-eight babies and thirty-eight children that were over five years of age. In Essex Street two small rooms in a six-story tenement were made to hold a “family” of father and mother, twelve children and six boarders.“

Benjamin was 20 years old when he landed in New York. Like many of the Jewish immigrants, Benjamin found work among the garment workers and cigar wrappers. He struggled in the garment district sweat shops for long hours and small wages–when there was work. The garment district of New York was a horrific place to work. It was unsanitary, crowded, low paying and dangerous. Four years after Ben started working there, the worst US workplace accident ever occurred when the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory caught fire.

New words needed to describe the horror

An eyewitness account by William G. Shepherd

I was walking through Washington Square when a puff of smoke issuing from the factory building caught my eye. I reached the building before the alarm was turned in. I saw every feature of the tragedy visible from outside the building. I learned a new sound–a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk.

Thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead. Sixty-two thud—deads. I call them that, because the sound and the thought of death came to me each time, at the same instant. There was plenty of chance to watch them as they came down. The height was eighty feet.

The first ten thud—deads shocked me. I looked up—saw that there were scores of girls at the windows. The flames from the floor below were beating in their faces. Somehow I knew that they, too, must come down and something within me—something that I didn’t know was there—steeled me.

What made this so horrible was that it was preventable. Supposedly, due to a recent spate of corporate thefts, the management had ordered the main exit door locked and bolted from the outside, and the starting point of the fire forced most of the seamstresses towards that locked exit. Their bodies were found piled one on the other as they clawed their way towards the door. Next, the one emergency fire escape landing collapsed and fell from the mass of humanity trying to make their way out. The owners and management, working on the tenth floor escaped via a private exit to the roof from which they were rescued.

The Triangle Shirtwaist factory was not unique, the same work place environment of oil lamps, over crowding, smoking, fine cloth clippings, lack of ventilation and blacked out windows were the norm for all garment factories. Add to this fatigue from twelve hour work days and no sanitation and you have the perfect recipe for tragedy. Fires were a constant, and the lack of any regulation or real workplace safety guidelines made for a constant pall of fear hanging over the workers.

Joe Simon’s memory is even more blazed into his psyche. His father was also a tailor, fresh off the boat in 1905, and looking for work in Rochester’s garment district. “There was always a lot of conflict between the factories and the laborers, who were openly recruited to join unions such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the United Garment Workers. As soon as my father arrived, he got himself into trouble as a union organizer and a “socialist”—“You take care of me, and I’ll take care of you.” The manufactures didn’t like it, and I think my father lost some jobs because of it. So he went into business for himself and worked out of his own house.” The Simon’s moved constantly as his father’s economic state drifted uncertainly. New York, Chicago, Detroit and other stops in between until they returned to Rochester. Despite the setbacks, Joe’s father always maintained the immigrants’ optimism and swore that this country’s pavements were paved with gold. But the factory wars continued.

For those that did strike, they faced brutal retaliation; either by being fired, harassed, shadow laborers, or even brutally beaten by hired thugs. Called Slammers—they were gangster strong arm men paid to soften up the opposition. The Unions did what anyone might have done—they hired other strong arm men from rival gangs to beat back the slammers. A horrible gang war erupted that lasted almost 30 years. History shows that the mobs used this practice as a way of infiltrating and finally controlling the unions and their large retirement funds.

A stern, but fiercely proud matron, Rose would help out with the occasional seamstress job, or shift at a bakery. They had settled on the afore-mentioned Essex St, and it was in their packing-box tenement apartment that Jacob was born. The family expanded a few years later with the birth of David, a rather large bundle of joy–the newspaper listed him at 16 lbs. By then they had moved two streets over to a slightly larger, but still dreadful apartment on Suffolk St.

The apartment was a typical tenement flat. Jack recalled: “We had a metal barrel right in the middle of the room that was our stove and that had a chimney pipe that went up into the ceiling. And we had a kneading table right behind the stove and the washtub where we took baths and washed our clothes. There wasn’t a bathroom; we took turns taking baths in the same room where we prepared our food and the toilet was down the hall; the whole floor used the same toilet. We had one little room with a dining room, if you want to call it that, but it was a little room with two windows and all the women would look out those windows and talk to each other from one floor above. But my mother did what she could and she kept the place very clean. She kept it as clean as a whistle.”

Such was the life and surroundings Jacob grew up in. The Lower East Side was a hellhole, possibly the most crowded patch of humanity on Earth, certainly not a fit place to raise a family, but it was not without its unique allure–especially for the children. Kids were resourceful, the stoops, fire escapes, and alleyways transformed into exotic locales for grand adventures. The street became Yankee Stadium, stickball games featuring kids with dreams of the Bambino swinging for the fences; roof tops gave air to dreams of Captain Eddie and “Lucky” Lindy, while Tom Mix chased Black Bart up and down the latticework of fire escapes and landings. The city was a breeding ground of disease, crime and talent—if you could survive.

Jacob Riis describes the neighborhood peaceful assembly at the end of a long day:

“Evening has worn into night as we take up our homeward journey through the streets, now no longer silent. The thousands of lighted windows in the tenements glow like dull red eyes in a huge stone wall. From every door multitudes of tired men and women pour forth for a half-hour’s rest in the open air before sleep closes the eyes weary with incessant working. Crowds of half-naked children tumble in the street and on the sidewalk, or doze fretfully on the stone steps. As we stop in front of a tenement to watch one of these groups, a dirty baby in a single brief garment—yet a sweet, human little baby despite its dirt and tatters—tumbles off the lowest step, rolls over once, clutches my leg with unconscious grip, and goes to sleep on the flagstones, its curly head pillowed on my boot.”

Children of the ghetto did not curl up and die from the fetid stale air of summer, or the agonizing, biting cold of winter. Instead, through innocence, and imagination, they staked out a world of wonder to call their own. In the summer, when PS #20 was closed, the small two room apartment, with the one bed shared by four, expanded when the steel fire escape became a bedroom for the two boys.

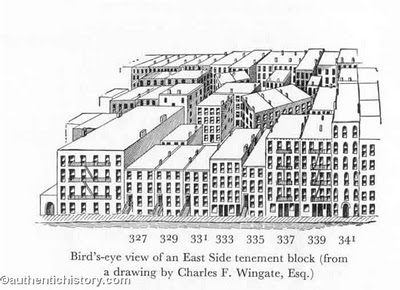

Typical tenement layout—close

Jack would recall that the times spent on the fire escape; dreaming under the starry skies was the nearest he would come to a summer vacation. Many an hour was spent up on the roof—just reading a book, or doodling away in a pad of paper. The fire escape was great for looking out at the world and imagining a life outside his immediate surroundings- maybe over the bridge he could see in the distance or the other side of the docks to the East, or maybe past the Allen Street El. It was so easy to daydream when the vantage point is above everything, and the world looks so small. “My mother once wanted me to have a vacation, so she sent me out on the fire escape for two weeks. And I was out on the open air for two weeks, I had a grand time, I assure you!”

It was a short walk down Delancey Street to the East River where the young mothers would go in the early morning nursing their babies along the cool bank watching the early morning trade. This was the only time of comfort and quiet peacefulness as the sun rose over Long Island and their minds drifted away from their stuffy, over-heated little rooms. Too soon they must rise and return to their kitchens and prepare the breakfast for their husbands and children as a new day starts again.

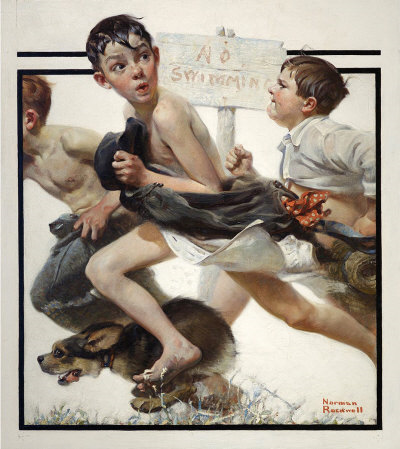

Pretty soon, that same river became the cherished goal of the kids, born in the swelter of the city yearning for a cooler place to escape. Taking their lives in their hands—whether naked, or with a small ragged bathing suit and adventuresome spirit—they sought the docks. It was a risky business, for the tides ran fast in the river and policeman caused no end of trouble. There was always a smaller boy sentinel–usually Jacob- whose “Cheese it, Cops!” fetches brown, slippery little bodies out of the water in quick time to escape the policeman, dressing while running at full speed was an accomplishment; to stay out of the water longer than the policeman remains in the immediate vicinity, unheard of. Drowning occurred of course, but every gang of boys numbered a life-saver. This recreation provided Jack with one useful thing; Greg Theakston explained; a swimming style where he would lead with his hands pointed out in front of his face, shoving trash and debris out of his way while he swam. This style lasted his whole life—even in his later personal swimming pool free of that same trash.

On hot days among the debris, the boys discarded all clothes and waded in among the trash, the fishmongers and bums

Norman Rockwell recalls

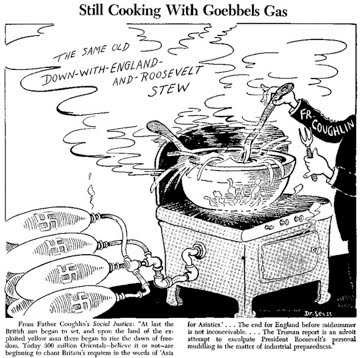

After the war, with the growth of anti-Semitism at home and abroad as well as the economic and social challenges posed by the Great Depression of the 1930s, times became harder. Anti-Semitism peaked in America in the interwar years, and was practiced in different ways by even highly respected individuals and institutions. Private schools, camps, colleges, resorts, and places of employment all imposed restrictions and quotas against Jews, often quite blatantly. Signs saying “No Jews, or Dogs Allowed” were common. Leading Americans, including Henry Ford and the widely listened-to radio priest, Father Charles Coughlin, engaged in public attacks upon Jews, impugning their character, designs and patriotism.

“The International Jewish plan to move their money market to the United States was what the American people did not want. We have the warning of history as to what this means. It has meant in turn that Spain, Venice, Germany or Great Britain received the blame or suspicion of the world for what the Jewish financiers have done. It is a most important consideration that most of the national animosities that exist today arose out of resentment against what Jewish money power did under the camouflage of national names.”

The International Jew 1920 Henry Ford

Egged on by Father Charles Coughlin, whose national radio broadcasts and newspaper Social Justice regularly blamed “Jewish bankers and merchants” for the world’s economic woes, groups like the Christian Front and the Christian Mobilizers terrorized Jews. These mostly Irish thugs roamed Jewish neighborhoods like the South Bronx, smashing storefront windows and vandalizing synagogues and cemeteries. On December 18, 1938 two thousand of Coughlin’s followers marched in New York chanting, “Send Jews back where they came from in leaky boats!” and “Wait until Hitler comes over here!” The protests continued for several months. In an ironic twist New York State Judge Nathan Perlman personally contacted mob boss Meyer Lansky to ask him to disrupt the Bund rallies, with the proviso that Lansky’s henchmen stop short of killing any Bundists. Enthusiastic for the assignment, if disappointed by the restraints, Lansky accepted all of Perlman’s terms except one: he would take no money for the work.

Nazi Bund rally in 1939 at Madison Sq. Garden

Lansky later observed, “I was a Jew and felt for those Jews in Europe who were suffering. They were my brothers.” For months, Lansky’s workmen effectively broke up one Nazi rally after another. Meyer notes, “Nazi arms, legs and ribs were broken and skulls were cracked, but no one died.” A tale is told of one such event, Lansky recalled breaking up a Brown Shirt rally in the Yorkville section of Manhattan: “The stage was decorated with a swastika and a picture of Hitler. The speakers started ranting. There were only fifteen of us, but we went into action. We … threw some of them out the windows. . . . Most of the Nazis panicked and ran out. We chased them and beat them up. . . . We wanted to show them that Jews would not always sit back and accept insults.”

Jack vividly recalls that even as late as 1940, the Bunds would hold rallies in Madison Square Garden. As well as hold summer camps in Long Island.

Ironically, with the rise of the Jewish Mafia, a newer, more independent, wealthier, and politically active Jewish presence grew in prominence as Jews took up roles in politics, finance, construction, social engineering, as well as entertainment. This mix of ambition and power forged a strong alliance. The Jewish Mafia rose and grew in power in direct proportion to its grooming political and judicial power.

The good Dr. Suess speaks out after Coughlin swipes from Goebbels

In several major cities, Jews also faced physical danger; attacks on young Jews were commonplace. In 1915, a young Jew named Leo Frank was lynched by a mob of southern whites after his conviction for murder was commuted by the Gov. of Georgia. Frank had been wrongly convicted of killing a young white girl who worked in the pencil factory that Frank ran. The anti-semitism that this stirred was such that Atlanta’s Jewish community formed the Jewish Anti- Defamation League and paid for his legal representation. Though there was no physical evidence against him, the all white, all-Christian jury only took 4 hours to convict him, all the time the public audience screamed “Hang the Jew!”

The case went to the Supreme Court and the decision was upheld, finally the Governor bowing to new evidence and the pleas from many, including the original court Judge commuted his death sentence. A few nights later a mob went to the prison and grabbed Leo Frank, then drove him over a hundred miles to the little girls’ neighborhood and hanged him from a tree. The townsfolk happily posed for pictures beneath the hanging body. A bit of irony as this case is also responsible for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan and a new wave of crimes against blacks and Jews. The mere mention of Leo Frank’s name was enough to invoke fear and terror in the minds of little Jewish children. The Jewish population galvanized itself to fight off such tyranny.

Joe Simon recalls; “The Jewish population of Rochester had strong ties to the tailoring business for many years. The owners of the companies were German Jews, and most of the factory workers were Jewish. As far as anti-semitism, we all learned to live with it the way other minorities have learned to live with their problems, even today. Early on I understood what integration and segregation meant, because it was understood that we wouldn’t move into this section, we wouldn’t move into that house, and so on. But rather than overt anti-semitism, it was in a relatively hidden form. Maybe you didn’t see it, but you knew what was going on. You’d go to a real estate agent and he’d say, “you won’t be happy”, that type of thing.”

Leo Frank swings as the crowd mugs for the camera

It was a rough time, with serious consequences; Jack talked of one day at Hebrew school. “Until the day I die I’ll never forget the wonderful table we used to sit at. One day an airplane flies over head and I get up to watch it. I slide over to the window and everyone was pushing and shoving each other, and some guy really shoved me out of the way—I knocked him clean out.” Even in the halls of religion, the law of the jungle prevailed. Close quarter recreation, that’s how Jack remembered it; everyone on top of each other. “You played handball and by accident somebody would hit the ball and knock a guy’s hat off somewhere and the next thing you know you are running the block while this guy is chasing you, yelling.”

“The block,”–that’s what you called your immediate neighborhood—that was your turf, your sanctuary . The result of a land carved up into small squares by wide avenues and concrete roadways, iron train tracks, and cobblestone streets. “It was a very lively place, but it was a mess.” “The neighbors were wonderful people, and they were fair people. They were the kind of people who spoke their minds, and despite the fact that they might have an argument with you one day; they would protect you the next. Why? Because you were their neighbor and you lived on that block and you lived in that building and you were part of them. That’s the way it was.” The block was an artificial boundary, to those inside; it could be inviting as a lazy rolling river or as harsh as barb wire to an outsider.

Jack hated the block, and the one next to it, and the one next to that. He began to walk, he expanded his world and went uptown, he saw the huge buildings, and the men in all their finery. He saw the champ, Jack Dempsey and had a marvelous conversation, and he met the middle weight champ Mickey Walker, and they sat and showed each other their artwork. He soon realized the world was much larger than his little block.

The Block by Romare Bearden squares and divisions

According to Jack, his father was also a scrappy person; not averse to mixing it up when pushed to his limit. But to Jack, his father was a gentle, kind soul, who doted on him. His heart was still back in his homeland, and he spent many a quiet time dreaming of his life back in Austria.

Mama Rose was more in the here and now, she was only five when she came to the U.S. and this country was what she knew—except for the legends and folk tales handed down by her mother. She spoke English very well. Mama Rose tried to calm down the young lad and bring some refinement to him. Once she purchased a violin for Jacob to learn and enjoy. But the street tough would have none of that and he promptly threw the violin out the window. No sissy stuff for him. Yet, Jacob was also a charmer; another skill a small guy needed on the streets. With an eager smile, on a square full face, full head of thick curly hair, dark flashing eyes, and a ready story, Jake would often talk himself out of a scrap.

As a young street rat he thrilled to the chase over the fences, across the rooftops, and down the alleyways. He loved the toreador-like avoidance of ice wagons and Arab lorries, hopping monuments, dodging missiles and the rush of adrenaline facing down toughs from the next block over. But it wasn’t all fun. “I saw a gang of guys coming up the street, and I was afraid. And so I ducked into this phone booth see? And these guys all started kicking the phone booth to scare the hell out of me, and I was scared out of my wits.” Jack told an interviewer. Street gangs meant an identity, you belonged to something bigger than yourself, and it offered security and status. The need to be accepted as a peer was strong. Jack would tell of a neighbor boy born a hunchback, who wanted so badly to belong to the gang. Since he couldn’t run, maneuver and brawl like the others, the young boy demanded that the members rub his hump for luck before entering a scuffle–it was his badge of honor. “I would start a fight if I thought there was a problem. I would be scrappy on that account. You wanted to show a guy you are just as big as he is, otherwise, they would take you out, and I don’t mean on a date.” But I didn’t like to fight. But I could. I did it very well.”

But being 5’4” small meant you were going to lose sometimes. “I got into one gang fight in the street and I was knocked out; flat unconscious. My guys walked me up five flights of wooden steps and left me at the door of our apartment. They made sure that I looked as good as possible lying there the next morning so the sight wouldn’t shock my mother when she opened the door. “all that for my mother. A mother was sacred.” “I made a mistake.” Jack told a reporter. “What was that?” he asked. “I was born short.” On the East Side that was a mistake because, well, the big guys beat up on the little guys. But I made up for it as much as I could, in meanness.” Jack laughed. “I would wait behind a brick wall for three guys to pass and I’d beat the crap out of them and run like hell.” I refined the meanness to help my own ego.”

Actor Jimmy Cagney, a Lower East Side alumnus, talks about the gang warfare in his biography. “About all this street fighting, it’s important to remember that we conformed to the well-established neighborhood pattern…We weren’t anything more than normal kids reacting to our environment–an environment in which street fighting was an acceptable way of life…We had what I suppose could be called colorful young lives.”

Actor John Garfield, was born Julius Garfinkle just a few blocks north on Rivington St. to Russian immigrants. His life was as bad as Jacob’s. He joined the local gang and reached a position of prominence. He says he that he learned “all the meanness, all the toughness it’s possible for kids to acquire.” “Every street had its own gang. That’s the way it was in poor sections… the old safety in numbers.”

Though his brother David was 5 years younger, he was very large and much heavier. His mother often dressed him sort of femininely. This attracted many of the gang members and local toughs to pick on him. Though David could usually handle himself, often the odds hit 3 or 4 to one. After school, it was oftimes that Jack would happen upon his brother in a pile of bodies. Jack would throw down his books, jump in the pile and whale away at the boys. The boys were tight. But being small wasn’t always a bad thing; it meant that often when Jack and David would go to the movies that Jack got in for the children’s fare. This left a penny or two for snacks. Brother Dave remembers it slightly different. He said it was Jack at the bottom of the pile and it was Dave’s bulk pulling him out of the fracas.

Joe Simon tells of the sibling relationship with his sister Beatrice. “Sure my sister and I would fight a lot, but that was normal. I took a lot of crap for her and got into a couple fights protecting her from neighborhood bullies. That’s what brothers do.” Yes, that is what brothers did. Families were important.

Local legends

Yet deep down Jacob was hurting; it was just so much useless macho posing and false bravado. Jake grew to hate the scurrying around like a rat, fighting over turf that didn’t really belong to him, trying to simply fit in. He had another side, a sensitive nature that preferred reading, telling stories, and most of all, drawing. Jake would listen spellbound to the Old World legends lovingly told by his mother. He thrilled to the tales of King Arthur, Robin Hood, and Tom Sawyer that he borrowed from the library. His favorite memories are sitting on the fire escape landing on a quiet cool afternoon reading a new book. He really loved the funny pages, spending many an hour absorbed in the riotous adventures of Krazy Kat, Jiggs and Maggie, and Barney Google. It was a short step to his first doodling. Yet his life on the streets required that mask of machismo, and reading and drawing did not fit into that culture. Kirby recalls, “In my neighborhood, book lovers were considered sissies. So I did my best to hide any book I was reading.” This internal conflict between his hard edged exterior, and sensitive nature would tear at him for many years.

In August, 1923 a gangland feud erupted between rival union-busters called the Little Augies, and the Rough Riders. During a massive shoot-out on Essex St, two innocent bystanders were shot and killed. The fighting seemed to end in late August when local gang hero Louis Cohen killed Nat Kaplan- the leader of the Rough Riders. The death of the innocents led to a huge out-pouring of police resolve. The threat to the people led to a harsher legal system and the rise of Thomas Dewey the renowned anti-racketeer. Actions have consequences.

Jack loved books, and the early 1920’s were a Golden Age for children’s literature. But to understand the market you must realize that books for children arose in the mid-1800’s when the steam Rotary web-fed letterpress allowed printers to make large quantity runs in a newspaper format. This led to mass market magazines that could be sold cheaply due to the mass quantities. Very quickly titles aimed at children arose. There were 2 tracks of magazines, the first was a digest sized pamphlet printed on cheap paper and sold for a nickel or dime and aimed at lower class outlets. These were called dime novels, or in England, the penny dreadful, based on their often bloody, vicious and lascivious nature of the books. In the U.S. western stories soon became the major theme, with horrid stories of Jesse James, or Buffalo Bill. They soon were seen as the home of guttersnipes and brigands. These were amazingly successful yet the complaints against them quickly expanded as they were perceived as negative influences. Kids continued reading them, sneaking them unknown into their houses, hiding them under beds, reading them under the covers. Soon zealots arose demanding them banned due to their salacious nature.

The other source was called slick magazines because of the higher quality slick paper. These could cost fifty cents or even higher-shutting out the lower classes. Yet the featured grand adventures by H. G. Wells, or Jules Verne, classics by Cooper, or Longfellow, or Stevenson, all lavishly illustrated by the best of the day; N.C. Wyeth, Mead Schaeffer, Herbert Morton Stoops, Hannes Bok or Frank Godwin sparking the imaginations of children everywhere. Magazines like Blue Book, St Nicholas, Youth Companion or American Boy dazzled children with their mixture of adventure and art. These were considered fine and upstanding examples for the child’s literary consumption.

Once the great depression hit, these mags became cost prohibitive and the two tracks blended into two new forms. The more expensive were printed as hard covered books, but they used the cheap paper that allowed the costs to remain low.

Some publishers took a different tack and produced a better printed book, with a middle range paper, and better binding to look like a quality book, yet the creative process used the cheaper writers and child oriented scripts common to the dime novels. In 1899, the son of a German immigrant wrote a novel; The Rover Boys at School. Edward Stratemeyer was a part time writer supplying short stories to dime novels and boy’s magazines. With the publishing of the Rover Boys novel Stratemeyer created a new genre of storytelling. In the next decade, dozens of Rover Boy novels were published as well as numerous other continuing characters –mostly children –in what became known as the juvenile series. Characters like Tom Swift, Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys became hugely popular. The theme was always the same, a group of unsupervised kids having great and wonderful adventures, sans parents. In 1905, under his newly formed Stratemeyer Literary Syndicate, he enlisted the assistance of other authors, mostly journalists, to flesh out a number of serial proposals he had started. They were paid a flat rate per book and he retained all copyright. The writers were to remain anonymous under their pen names, which caused much controversy and confusion in later years in discerning who was behind most of the works. Considered “work for hire” the writers would receive none of the benefits given to artists by the Copyright laws. This assembly-line separation of labor would become a template for much unaccredited fiction work. The juvenile series would come to dominate children’s fiction for the next 30 years.

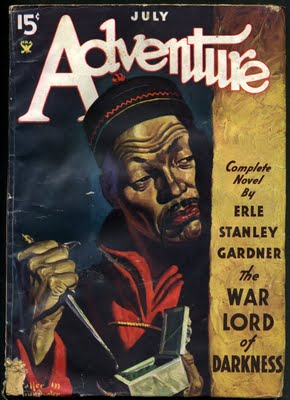

The other great source of juvenile literature was known as the pulps. The name pulp comes from the cheap pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. By using the cheaper material, during their first decades, pulps were most often priced at ten cents per magazine, while competing slicks were 25 cents apiece. Pulps were the successor to the penny dreadful, or dime novels, and short fiction magazines of the 19th century. Although many respected writers wrote for pulps, the magazines are best remembered for their lurid and exploitative nature and sensational garish cover and inside art. These were considered the lowest form of literary accomplishment, often considered little more than pornography. The best of the pulps was a magazine named Adventure. During its prime period, the magazine was edited by Arthur Sullivan Hoffman. Drawing some of the best new writers, such as H. Rider Haggard, Raphael Sabatini, and Damon Runyon, the stories were a cut above the rest. The covers were from the best of illustrators, and they shied away from the almost pornographic depiction of women on their covers. Adventure was their calling, not torture, and sexual depravity. By the thirties a new group of writers emerged including one who will be mentioned later- Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. The magazine was so successful that they started a letters page, and an in-house group that got together and formed clubs. Adventure‘s letters page, The Camp-Fire featured Hoffman’s editorials, background of the authors to their stories and discussions by the readers. At Hoffman’s suggestion, a number of Camp-Fire Stations – locations where other readers of Adventure could meet up – were established. Robert Kenneth Jones notes that Adventure readers “often wrote in to report on meeting new friends through these stations.”

By 1924, there were Camp-Fire Stations established across the US and in several other countries, including Britain, Australia, Egypt and Cuba. Adventure also offered Camp-Fire buttons which readers wore. No other book was so interactive with its readers.

Though most were of the cheap, lurid, sensationalistic nature, there was no shortage of reading material to stoke little boys’ imaginations. Interactive publishing became acceptable. Juvenile series like Poppy Ott and others added in their own letter pages and reader comments sections.

There was public outcry over the lurid prose, and misogynistic nature of the pulps. Writer Robert Brown wrote;

“Are Pulp Magazines worth reading? Do they cause brain burn? The answer is a simple yes to both questions. Let’s face it fans of the pulp, they are trash. Sorry, I don’t care what half-baked intellectual rebuttal you have to present, the truth about these magazines is that they were put out for the lowest I.Q. in the reading market and they show it.”

Other historians see it differently; Edmund Pearson sees the rancor as a result of competitor in-fighting;

“It is perpetually useful for each generation to see how much unnecessary anguish has been suffered in the past over things which were really harmless . . . They were never immoral; on the contrary, they reeked of morality. . . Indeed, there is reason to believe that many of the superstitious beliefs about the harmfulness of the dime novel were eagerly fostered and circulated by agents of the “respectable” publishing houses, to whom any books which sold for ten cents was grossly immoral, for that very reason.”

In response to these attacks, Street and Smith- a large publisher responded;

“They [other periodicals and story papers of the day] will discover, when it is too late, perhaps, that the people of the United States will not sustain papers whose editors gather up all the filth from the gutters and dens of infamy to make their columns “spicy.” A paper, to obtain a permanent circulation, must inculcate good morals and pay some regard to decency.

Either way, the kids loved them.

Top writers and the focus on adventure, not heaving breasts

On his way home from school one rainy afternoon, Jacob looked down and in the gutter was a discarded copy of a gaudy science fiction pulp magazine. “Something on the cover I had never seen before—the cover was amazing! One of Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories; space ships and futuristic cities. At that moment, something galvanized in my brain.” Kirby reminisced. “I think it was my first collision with a question. Gee, why couldn’t there be things like that?” A lifelong fascination with science fiction had been ignited.

Garish, colorful and always protruding bosoms

George Comet, a close friend told Greg Theakston: “Jakie and I went to parochial school together when we were about eight years old. He was always telling stories and drawing pictures. One day he did a caricature of one of the Rabbis. Unfortunately, the Rabbi didn’t see the humor and Jake got the strap. He always had a good story to tell. Once in a while the Rabbi would arrive for the day’s lesson in the midst of one; the rabbi would smile and allow him to finish.”

School was a mixed bag for Jacob. The macho posing and fighting was still a constant. “Sometimes we would call the teachers names. Yes, to their faces! They would chase us through the halls. Some guys would do worse. I am not talking about gentlemen. These were rough kids. We would fight in the gym, in the classrooms, in the hall—anywhere we had room enough to swing our fists. We would be out in the yard and some guy would pick a fight with another guy. The next thing you know you would have the whole yard fighting.”

“We had fine teachers. And so, despite the fact that we’d be running loose, just doing what we liked like any other kids—playing stickball or baseball or boxing somewhere—we had a fine schooling. I had Shakespeare in the eighth grade. I had a really good history course.” P.S. 20 (the old school on 45 Rivington St.) had other allures, such as a first rate library, just stocked full of adventure tales, and mythology and any type of book to get a young heart racing. Jack spent many hours searching through the inventory and reading his fill. The school also had a good drama curriculum. Its most famous alumni were Edgar G. Robinson, Paul Muni and the Gershwin Bros. Jack liked the idea of acting, and though he would laugh later and say that his acting consisted of the scenery falling on him, he must have shown some promise. He was given a prized part in the R.C. Sheriff play Journey’s End when the school put on a production. Ironically the role of Raleigh is that of a young naïve but eager soldier who loses the use of his legs during a battle. Hollywood must have looked a bit closer to the budding Cagney.

In Jake’s world there were well-understood social barriers. Fences, both physical and mental, meant to keep the lower classes separated from the swells. There was one great equalizer. The silver screen: nothing inspired the Depression era kids like the thrall of the movies. The local movie houses even let in Jewish kids. As Kirby related to an interviewer; “Movies were my refuge. It (the ghetto) wasn’t a pleasant place to live in, crowded, no place to play ball.” It was this fantasy siren song that called the young Jacob Kurtzberg. Every Jewish kid knew that Jews ran Hollywood. He dreamt of breaking free from his tenement prison and heading to Hollywood to make movies, as had his idols — and fellow East Siders — James Cagney, Jimmy Durante, and Edward G. Robinson. The Little Rascals left an indelible mark. The Marx Bros. and John Garfield made him laugh and cry. “I think I was brought up by Harry Warner. Whatever movie I was watching I would see it about seven times and my mother would have to come and get me out of the theater. I believe the naturalism and the drama that was inherent in the pictures left an impression on me that I wanted to duplicate.” The kid gangs, and the noirish German. expressionist movement really caught his eye. The shadows, the tension the movement of the camera all forged a place in his psyche. The lure of Hollywood, and moviemaking would inspire Jacob all his days. “Our generation was a movie generation. I saw myself as a camera.”

Oh those movies Jack loved them all

Inspired by his mother’s folktales, adventure stories, the comic strips, movies, and now, the garish art of the pulp magazines, the neighborhood became his canvas His artwork filled tablet after tablet, adorned school assignments, even covered the tenement walls and floors. His scribbled images would sometimes get him into trouble, but his easy charm and affable nature often got him off the hook. Jack tells of a meeting between Harold Hinson, the apartment building superintendent and his mother. “After quickly caring for a simmering pot, Rose followed Harold to a landing and looked in amazement at what her little Jakie had done. There it was, black chalk on white painted wood, a diorama from the great imaginings of a child.”

“As she examined the work in earnest, Rose could not resist a breathy “Oh my!” For such a young boy, Jakie’s imagination was on fire. Oddly shaped flying craft soared overhead as strange creatures swarmed over bizarre landscapes and structures. It was a war of creatures and machines, a conflagration of cosmic proportions. Young Jakie had managed to cover more than twenty feet of whitewashed wallboard, from the staircase landing to the water closet door, with extraterrestrial mayhem.”

Jacob’s parents would impress upon the boy the need to learn a trade, they wanted him to put his art behind him and think of his future. They would take his pulp magazines away from him. But Jacob could not stop drawing; it was taking over his life, it was what he knew he had to do to get off of the streets.

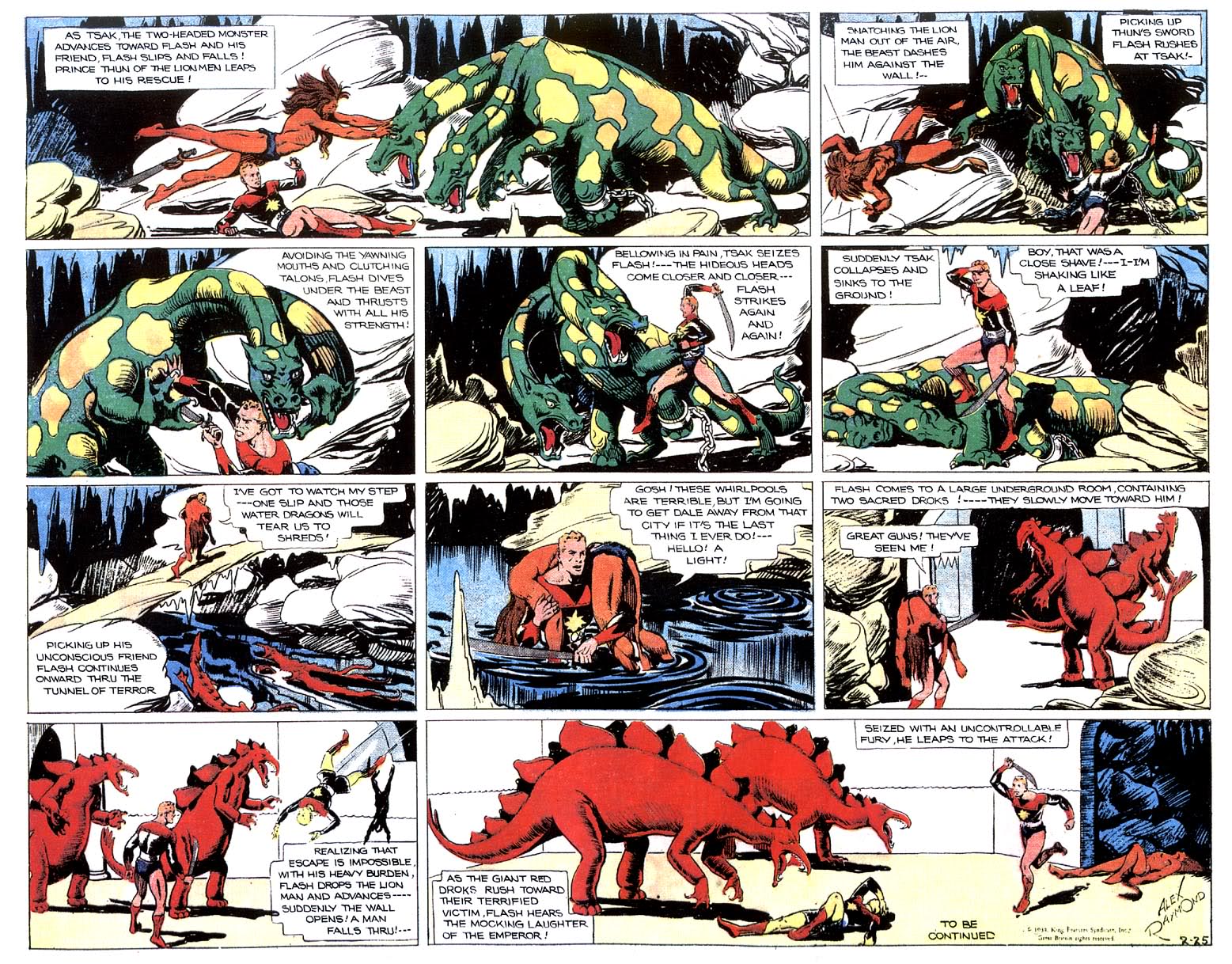

Jack’s art schooling was never formal, more an osmosis from the many inspirations found in his reading. Jacob’s teachers were Chester Gould, Hal Foster, Fred Paul, and Milton Caniff, the acknowledged superstars of the funny page adventure strips, alongside book illustrators like N. C. Wyeth, and Howard Pyle. Yet when pressed, it was always Alex Raymond, of Flash Gordon fame, that he would point to as his most significant inspiration. “He was a wonderful illustrator. His bodies had flexibility and he had a beautiful line to his drawing. I guess I wasn‘t the only admirer of Raymond, and I’m proud to say I copied him unmercifully. Well, I didn’t want to take his style exactly, but I took what I liked in his work.” Carl Barks considered Raymond the embodiment of all things good in cartoon art.

Alex Raymond- beautiful figures, fine lines and scary monsters

Previous – Preface | top | Next – 2. A World Divided

Thank you so much for doing this. Stan was my brother and I miss him very much. This is a great honor for him and his family. We are very proud of all the work he did for this.

I am spellbound by this! Mr. Taylor’s analysis has come along at just the right time for me. I’m only beginning to discover Jack’s work in earnest. This biography is adding such depth to the comics I’m reading. Thank you!

Stan was a friend of mine and one time neighbor. I met him through the friendship of his wife Annabelle and my girl friend Kathy. He was a deep thinker and a likeable eccentric man with a great imagination. I am thrilled that he is finally getting some recognition for is abilities. We both shared a great love for all things Kirby. RIP Stan your finally in the Kirby realm of the NEW GODS.

It’s nice to hear from you, Dale! Thanks. – Rand