Leonard Pitts, Jr., a commentator, journalist, and novelist, interviewed Jack Kirby in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. A transcript of the interview was included in the papers that Greg Theakston gifted to the Museum a few years ago. A nationally-syndicated columnist, Pitts was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 2004. Thank you, Leonard, for allowing this interview to be presented on the Kirby Effect. – Rand

PITTS: Let’s start with a little background-the “origin” of Jack Kirby.

KIRBY: I was born on the Lower East Side of New York. It was a restricted area in the sense that it was an ethnic area. And it was at a time when the immigrants were still coming in and they settled in certain parts of New York City, among their own kind.

We had blocks of Italians and blocks of Irish and blocks of Jews. I was born among the blocks of Jews. Strangely enough, our school curriculum was very good and our subject matter was very good. We had fine teachers. And so, despite the fact that we’d be running loose, just doing what we liked, like any other kids– playing stickball or baseball or boxing somewhere– we had a fine schooling. I had Shakespeare in the eighth grade. I had a really good history course.

I can’t say I was great in math (laughter), but in a very strange sense, my schooling was very good–all through junior high and high school and elementary. Later on, I even went to industrial school, because I understood that they had drawing tables there and I wanted to practice drawing.

PITTS: What years are we talking about?

KIRBY: We’re talking about the middle ’30s. I was born in 1917. I’m a first world war baby and I was brought up with two wing airplanes… the Empire State Building wasn’t there yet, the Chrysler building wasn’t there when I was born, and Von Richthofen was the guy they were all talking about… flying aces and pulp magazines.

The strange fact was that, on my block, we hadn’t even gotten to the pulp magazines. I found my first pulp magazine floating down the gutter on a rainy day toward the sewer and I picked it up because it had a strange looking object on it. It turned out to be a rocket ship. It was one of the first Hugo Gernsback Wonder Stories.

I didn’t dare to be seen with it, so I just picked it up and hid it under my arm, took it home and I began reading it and I learned to love science fiction.

PITTS: That was your first exposure to sci-fi?

KIRBY: Yes. I wouldn’t say it was an intellectual explosion. I’m still bad in math. I’m a lousy electrician– I couldn’t fix a plug. But I am interested in the other side of knowledge, the cultural side of knowledge and the truthful side of knowledge. I’m looking for the gaps that I know exist and of course, I’ll never get the answers, like everybody else. So I feel I live with very interesting questions.

PITTS: It’s more fun living with the questions for you, I gather.

KIRBY: Well, the questions are the things that make good stories, in my opinion.

PITTS: Getting back to your early years, it must have been tough, coming up in an already-poor neighborhood during the Depression.

KIRBY: And I also made another mistake.

PITTS: What was that?

KIRBY: Being born short.

PITTS: Why was that a mistake?

KIRBY: On the East Side that was a mistake because, well, the big guys beat up on the little guys. But I made up for it, as much as I could, in meanness. And of course, that’s very stimulating.

I was still being brought up on peasant stories; my mother came from Europe and she’d been a peasant and that was the area where the Frankensteins and the Draculas came from and it was entertainment for the people. Nobody had TV, and that was the way peasants would entertain themselves– by telling these stories.

PITTS: Was that your main form of entertainment?

KIRBY: My main form of entertainment was the early movies, in which I could see a Cagney, or a Edward G. Robinson or the Marx Brothers– all those old films, which I loved. My mother would have to come get me out of the theatre after the seventh performance.

I like entertainment. I’m an innate admirer of good entertainment. I’ll listen to MTV, I’ll listen to Mozart, I’ll listen to anything that has a good element in it. You know as well as I do that any kind of music can be written badly and it can be written wonderfully. I admire a top performer in any field.

I once drove a beat-up-Chevy, which was given to me by a garage man because he was fixing my car. And that beat-up Chevy was the best car I ever drove, because his son loved engines and he was an artist with an engine. There was nothing, absolutely, wrong with that car except a few dents. It was a joy driving that car, because whatever he did to that engine would transmit itself to the wheel and I could feel that, and I enjoyed it. That fella was an artist in his own right, and he didn’t have to play a note on a flute. An artist, to me, is someone– a professional– who does his work well.

PITTS: There was not a lot of money rolling around your neighborhood, so I guess any entertainment you got could not be too expensive.

KIRBY: I can tell you that I fought my old man for a copy of a quarterly Wonder Stories, which I never got, ’cause it cost 50 cents. I later bought that magazine. Maybe 30 years later, I bought that same magazine for 5 dollars. By chance I came across it in a bookstore. That was the issue I’d wanted, and I’d missed it.

ROZ KIRBY: As a youth, you were working, selling papers and all that stuff…

KIRBY: I admired all the Sunday papers. I admired the comics, because the comics were large and they were colored beautifully and they held an attraction for me. Possibly, that may be the reason I gravitated toward them, like a lot of fans gravitate toward comics today. I get letters from brain surgeons and I get letters from guys in drunk tanks; they all admire comics. That runs a large gamut.

ROZ KIRBY: [TO KIRBY] I think he wants to know what you did in those days to make a dollar.

KIRBY: What I did in those days to make a dollar? Nothing. I played handball, until, at the age of 17, it was traditional for your mother to roll you out of bed and tell you to get a job.

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] Didn’t you help your father with the pushcart? You did a lot of those things.

KIRBY: Oh, yes, I delivered papers. I could go through the whole routine. I drew numbers on paper bags so they could be put on pushcarts– “Onions-10¢ a pound” or something like that. I delivered paper and, being the smallest guy there, when they threw the papers off the truck at the news building, all the big guys would step right over me and get their papers first.

PITTS: That’s the second time you’ve mentioned being a smaller guy and implied something about having to be tough. Did you fancy yourself a scrapper?

KIRBY: Yea. I would wait behind a brick wall for three guys to pass and I’d beat the crap out of them and run like hell. I refined the meanness to help my own ego. I think everybody needs a little ego. I felt that I deserved an ego as well as the next guy. That’s why I also gravitated toward the gym. I was a very good boxer. I was a good wrestler. When I was drafted in the Army, out of a class of 27, just me and another fellow graduated from a judo class.

PITTS: Superman came out when you were in your early teens– your adolescence. Were you at all aware of him at the time?

KIRBY: Everybody was. Superman was an immediate hit. From what I understand, these two messenger boys came in from Ohio and they submitted this 10-page script called Superman. In order to fit it in the magazine, they cut it down to six, and they put the magazine out and the magazine sold out. They didn’t know what sold the magazine out, so they put out another issue and included Superman and the magazine sold out. That went on for three issues, until they found out it was Superman that was doing it. Superman was the psychological backbone for a lot of fellows who couldn’t make it– or felt they couldn’t make it.

PITTS: What did you think of it? Did it encourage you to become involved with comics?

KIRBY: Yes, of course. It galvanized me.

My first job was with Max Fleischer, the Fleischer Studios, animating Popeye. I was about 18. And of course, that meant working at a light table. There were rows and rows of tables, and that began to look like my father’s garment factory. I felt, that’s not what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to work in that kind of place– although it was a very nice place, the executives were fine people. And. of course, the Fleischer Studios were noted for their wonderful animation and Popeye speaks for himself. Their animation speaks for itself. But it wasn’t my kind of thing.

Then I went to a small syndicate called the Lincoln Features syndicate. They had 700 weekly papers, and I had the opportunity to do editorial cartoons, sports cartoons. I did a thing called “Your Health Comes First”, in which I was a doctor and I gathered information on how to cure your colds and what to do for the vapors. Of course, I didn’t do anything that was critical in any way. I don’t think I was knowledgeable enough. I just stuck to the things I knew, and I got as much information on them as I could.

I did a cartoon on Neville Chamberlain when England and the Allies gave Czechoslovakia to Hitler. Having been raised in a gangster area, and knowing gangsters as I did, I knew Hitler. And so, I did a cartoon in which I showed Chamberlain patting this big boa constrictor on the head, and there was a bulge in the center of the boa constrictor, which I labeled Czechoslovakia.

I got bawled out for that. My boss said, “You’re only 19 years old. You don’t know much about politics and these things.” And I said, “That’s true. But I do know a lot about gangsters. And I do know a lot about politicians because I’ve seen them in my friend’s restaurant.” I said, “I feel I can do editorial cartoons fairly well.” He said, “Spring is coming up– why don’t you stick to baseball and spring training?” And of course, I did. I didn’t want to have any large contention with my boss and, times being as they were, I did as I was told.

PITTS: Before we talk about the next step in your career, let’s back up a little and talk about your training.

KIRBY: I went to Industrial school. I had to take auto mechanics in the morning and art in the afternoon. This was after I graduated high school. I understood they had drawing desks there and they had art materials. That was fine for me, because that was what I was looking for. It wasn’t an extensive art course, but I’m glad, because it allowed me to do what I thought was right in my own way. I began to evolve my own style, with the smattering of anatomy that I got.

So, in the morning, I had to haul trucks out of the East River with the other fellas. Then in the afternoon, I took an art course– such as it was.

PITTS: So you were already fascinated by art even before you got to school.

KIRBY: Yes I was. I liked art. I liked good illustrations. They got me praise, they got me trouble. I suppose that’s life.

I belonged to the Boy’s Brotherhood Republic. It still exists today. We had our own mayor. A fella called Harry Slonaker, he came from the Midwest, where they had a BBR. And he organized a BBR there. He got us our own building, and we took care of our own gym, we had our own mayor, we had our own judge and prosecuting attorney. If anyone defiled the building, he went on trial. I became the editor in chief.

And of course, naturally, we began to act out our own opinion of ourselves. We copied the people we saw in the movies, so when a fella came down for trial, they came down with eight lawyers and an overcoat hanging over his shoulder like Edward G. Robinson. That was a lot of fun.

Our athletics consisted of playing football without equipment. That’s where we got bruised up, because we would play teams that did have equipment. It was in that kind of atmosphere that I was brought up. I idolized my mother and father. Everybody else did. You’ll find that the gangsters did. Mothers were sacred.

PITTS: You keep mentioning the gangsters. Were they the heroes of a poor neighborhood like yours?

KIRBY: No. They weren’t the heroes. The gangsters were just guys who wanted the $400 suits, and they wanted them now. I didn’t care when I got mine. I didn’t care what I wore. The gangsters– contrary to people’s opinions– were just ordinary guys who died very young getting their $400 suits. They were guys who wanted money fast, and they paid for it.

PITTS: Are we talking about any of the “name” gangsters?

KIRBY: Yes, there were big-name gangsters. Murder, Inc. came out of my area. A lot of other gangs. There were shootings every Friday night in the candy store. I once got locked in a wooden telephone booth. Fifteen guys began to kick the booth and kick the door down; I was a nine year old kid and scared stiff, but they did it for kicks.

Around the East Side , there wasn’t too much to do, and you had to find something to do. These fellows developed rough games and they lived a rough life and they died in a rough manner.

PITTS: What happened for you careerwise after the Fleischer studios?

KIRBY: Comics is strictly an American invention. The first comic, I believe, was an editorial cartoon done by Benjamin Franklin who had a contention with a businessman. If you add two or three panels to an editorial cartoon, you’ll get a comic strip. In 1903, I think, they had the Yellow Kid which was the first American comic strip. If you add pages onto that, you get a comic book.

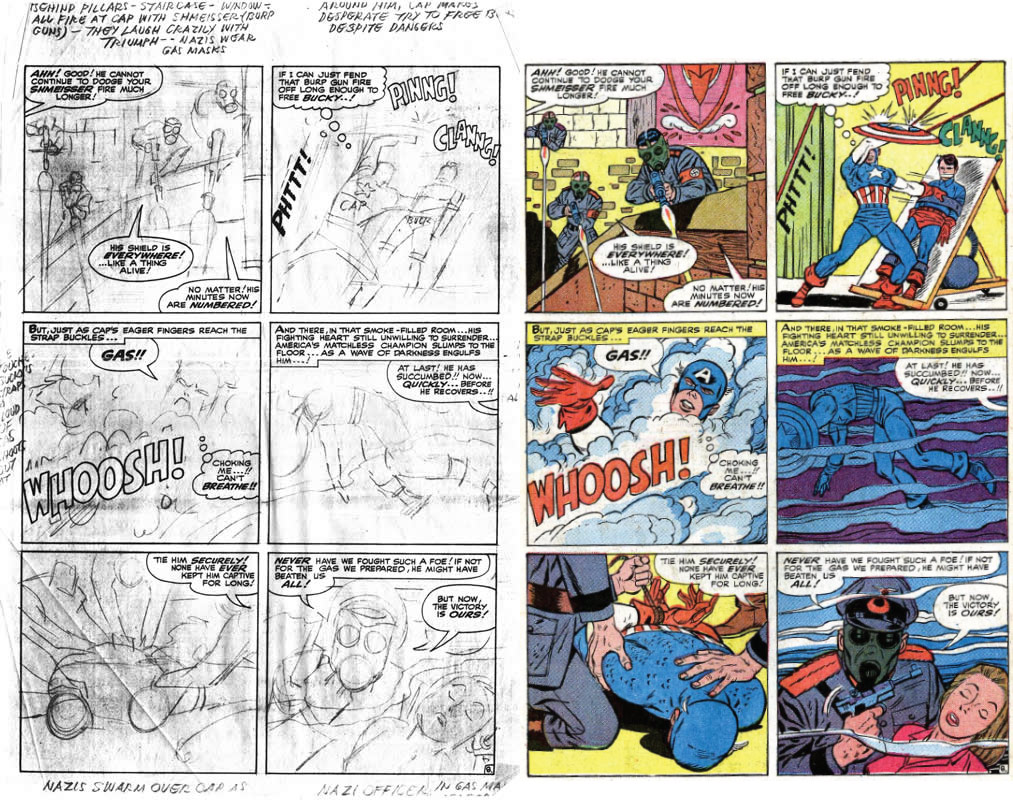

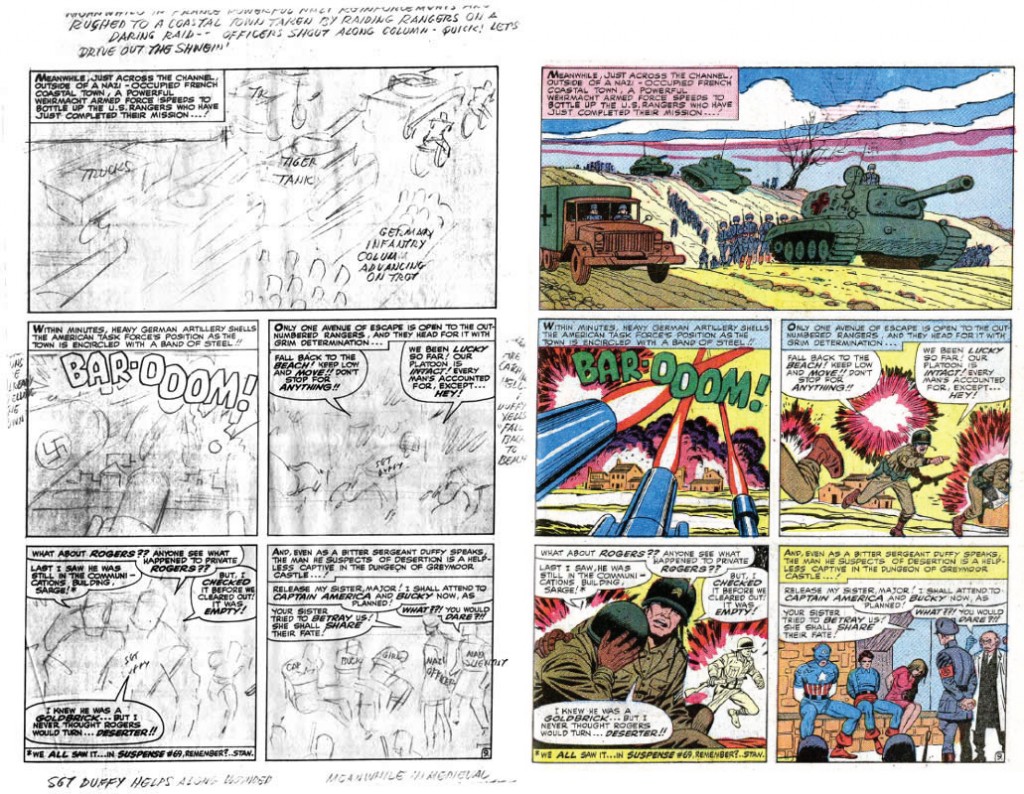

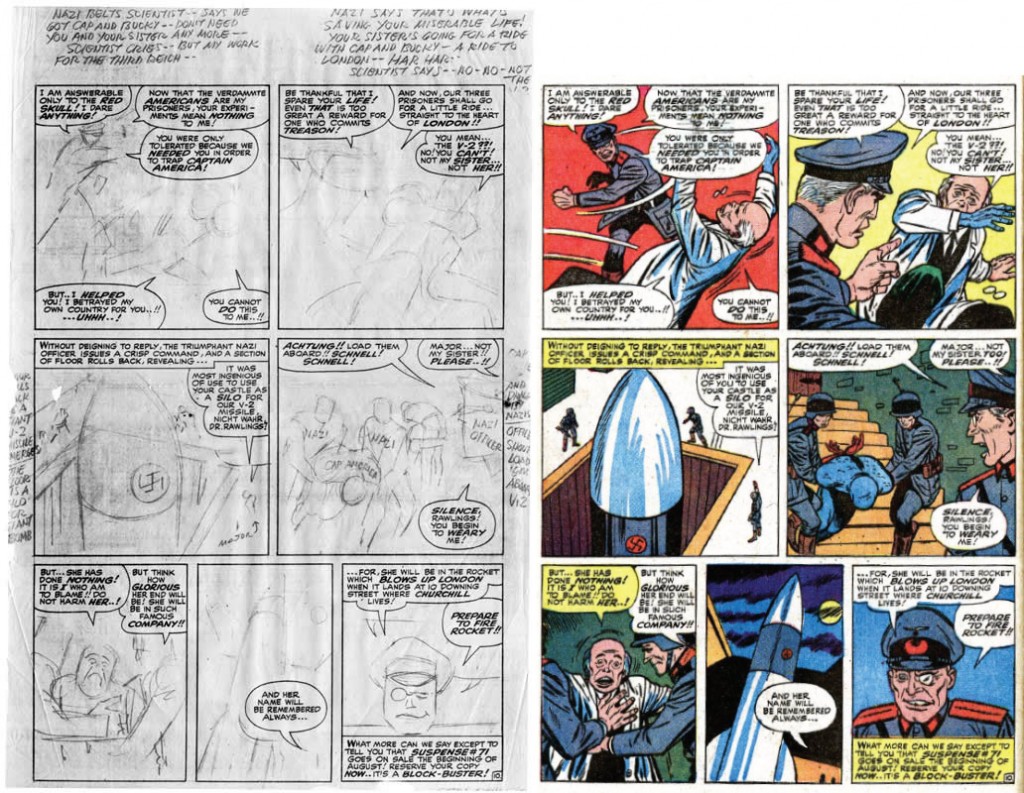

PITTS: When was it that you created Captain America?

KIRBY: Captain America actually came in late ’39. I originated Captain America with Joe Simon. Joe Simon and I got a studio apartment and we were turning out comics. Joe is a big guy; he was a middle class guy, and I had never seen middle class guys. They all wore great suits and were taller than I was. I gravitated to Joe, who is a wonderful guy and a good friend, and he had a rapport with the publishers. Joe did the business, actually, for us both. I did the stories and the pencils. Joe was just as good at it as I was– he could pencil and ink and write stories, as well. We were both creating things to sell to publishers and Captain America was one of them. We sold Captain America to Atlas, which later became Marvel.

PITTS: Let me just toss out the names of some of your most famous characters and, if you would, just give me an idea of what thought process went into creating them. Let’s start with Cap.

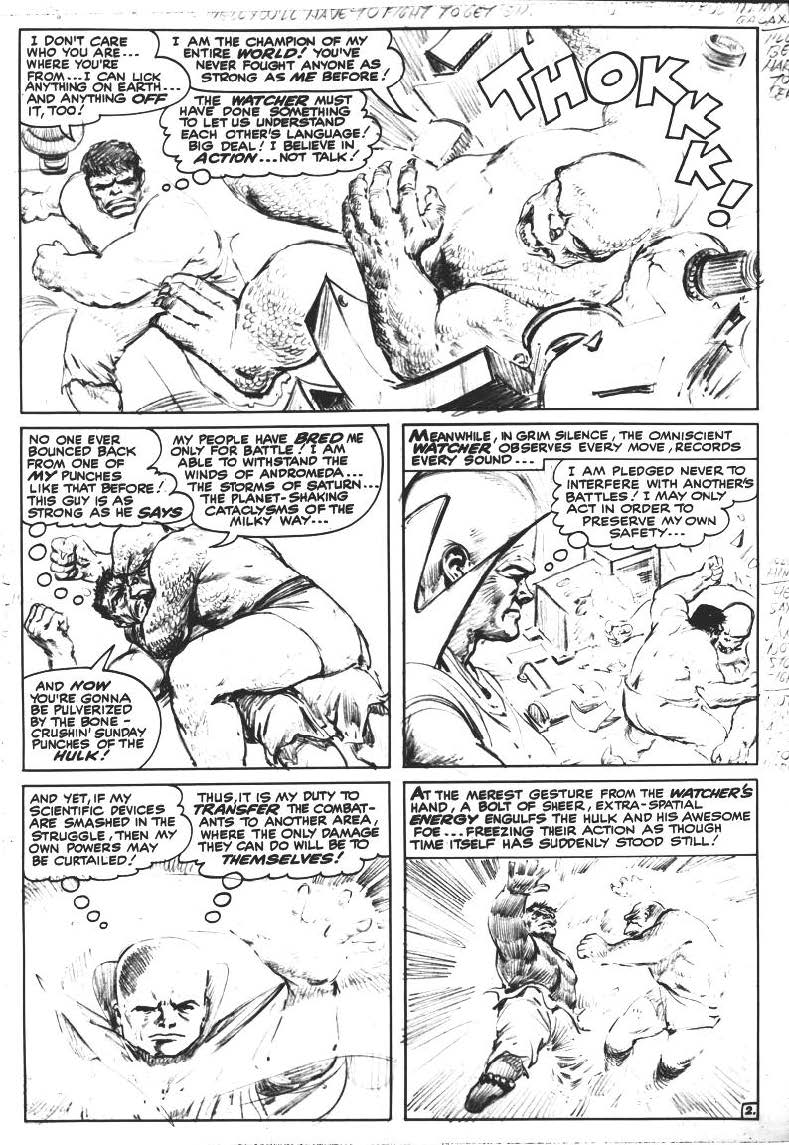

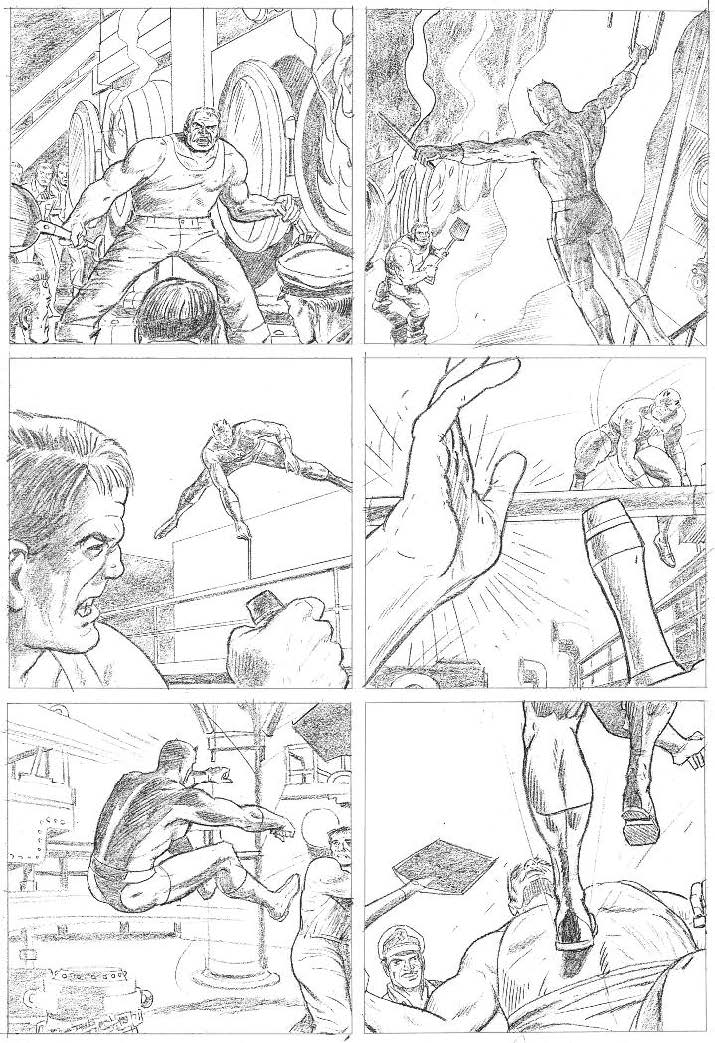

KIRBY: Captain America was myself. Captain America was my own anger coming to the surface and saying, “What if I could fight 25 guys? How would I do it?” And I figured it out and it would become sort of a ballet, in which Captain America would fight 25 guys and I’d work it out so he could lick ’em all. Of course, in real life, I’d probably get smeared. In real life, it doesn’t work out that way. You can’t keep track of everybody and you don’t know what the next guy ia doing, but over here, I could.

What I did, was an artistic punch-out. That kind of thing was very popular then. I didn’t realize it until I was told about the sales figures.

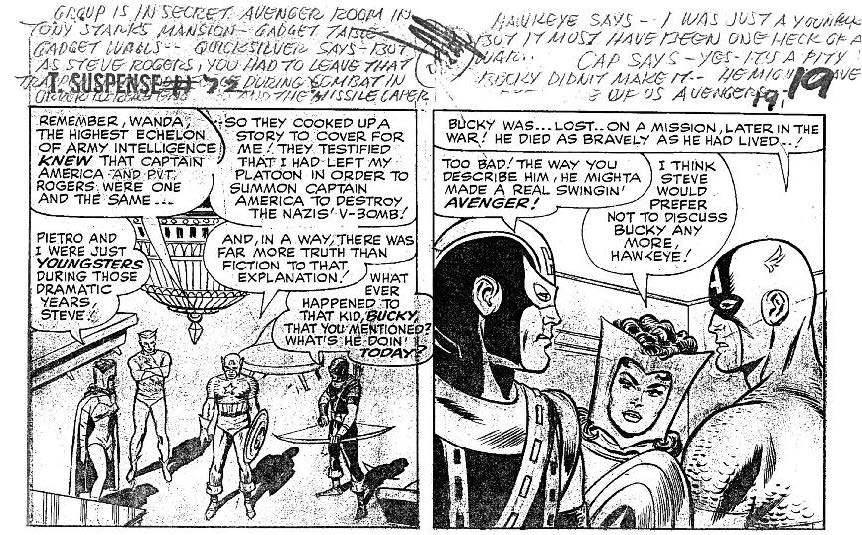

PITTS: I have heard that you haven’t always been particularly pleased with the way the character has been handled since you created him. I’m thinking specifically of the storyline Steve Englehart did in the ’70s, wherein Steve Rogers was disillusioned by government corruption and gave up his Captain America identity.

KIRBY: Well… I haven’t kept in touch with comics for a long time. I leave Englehart’s version to Englehart. I respect Englehart– Englehart is an individual and I feel every individual should do his own version. Englehart isn’t Jack Kirby. Englehart hasn’t got my background, Englehart hasn’t got my feelings. And so, of course, I’m going to do a different version of Captain America. Englehart will do his own.

I always felt my job was selling magazines, which I did. I put all the ingredients that I thought would sell that magazine, and they sold. Captain America sold 900 thousand a month at one time. Of course, I don’t know what it’s selling today.

Pitts: So, you’re saying you’ve never had any problems with any of the different versions of your characters?

KIRBY: No. I respect the individual. If that’s the way he sees it, he’s got the right to call it, because he’s hired to do it.

Pitts: Let’s talk about the Boy Commandos.

KIRBY: The Commandos were my own friends, my own street gang. Except that at that time, I felt it was timely to make them Europeans because that was what was going on. It was a timely subject. They had commandos at that time. They were small bands against great armies and I respected them. I felt they were a reflection of my own gang. Us against the world. Us against the guys on the next block.

I was the first one to introduce kid gangs in comics, because that’s the way kids are. They’ll hang around in groups and they’ll exclude who they want and they’ll include who they want. It’s the kind of atmosphere I was brought up in and it hadn’t been done in comics. They sold very well. The Newsboy Legion was the same kind of comic strip. They were my own friends. And of course, we all called each other nicknames; we all had nicknames– Spike and Mike, Slink.

PITTS: You weren’t cool without a nickname.

KIRBY: Oh, sure. I was the only one who didn’t; they called me Jackie. But that was the way things were, and I accepted it. I think in a way, it was a good thing. Although different ethnic groups fought each other, we got to know each other. We got to know each other in the classrooms, we got to know each other in the subway.

An Italian woman came over to me and asked directions. And of course, without any knowledge of Italian, I couldn’t tell her. But in a way, I treated her like my own mother. I felt that mothers are wonderful and it didn’t matter what ethnic group they belonged to. I felt if they were the mothers of these boys, there was no reason I couldn’t be friends with them.

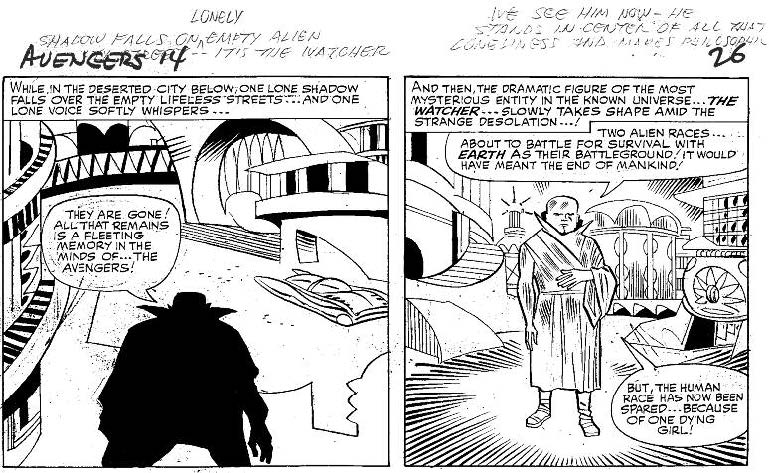

PITTS: Let’s skip ahead ·and talk about your time at Marvel in the ’60s. I’d like to get your version of the famous tale of t he creation of the Fantastic Four.

KIRBY: My version is simple: I saved Marvel’s ass. When I came up to Marvel, it was closing that same afternoon, Stan Lee had his head on the desk and was crying. It all looked very dramatic to me, but I needed the job. I was a guy with a wife and three kids and a house, and I wanted to keep it. And so, having no rapport with Martin Goodman, who was the publisher– Stan Lee was his cousin– I told Stan Lee that we could keep the place going. And I told him to try to tell Martin to keep it going, because we could possibly revive it.

It was a bad time. It was a time when major publishers were folding and comics in general suffered bad press. It was a time when the public itself was being anti-comics-ized by people like Frederic Wertham and the movies. It was an unregulated industry. Finally, we did get a board to regulate the industry and put down rules; we formulated an atmosphere of legitimacy, but that had to take time and meanwhile, the comics were folding right and left.

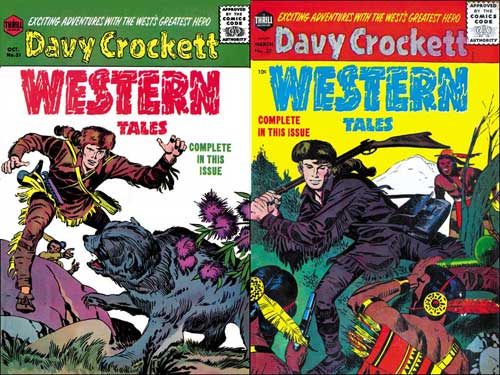

Of course, Marvel had magazines and didn’t need comics, so they were ready to fold. They had other things to rely on. I began with doing monster stories and westerns; I did my best on the Rawhide Kid, and I did my best on the monster stories. This was in ’59. Joe and I had our own publishing company which we dissolved; Joe went to work for one of the Rockefellers and I went back to Marvel. Comics was the only thing I knew, really, and could do well.

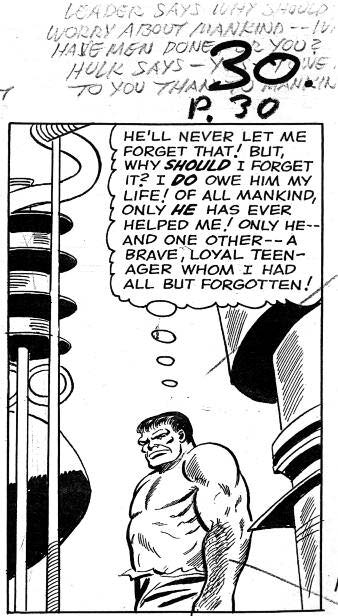

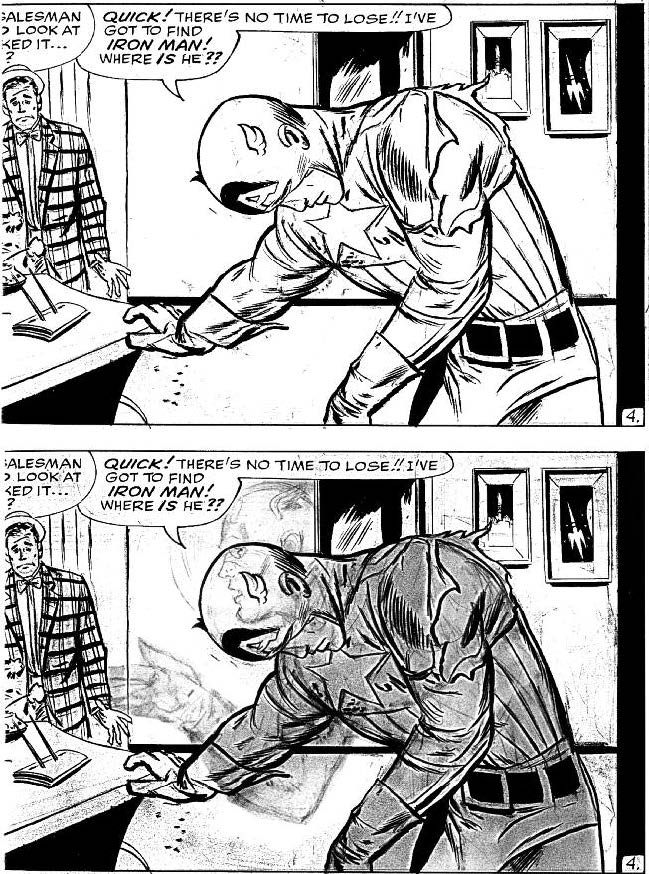

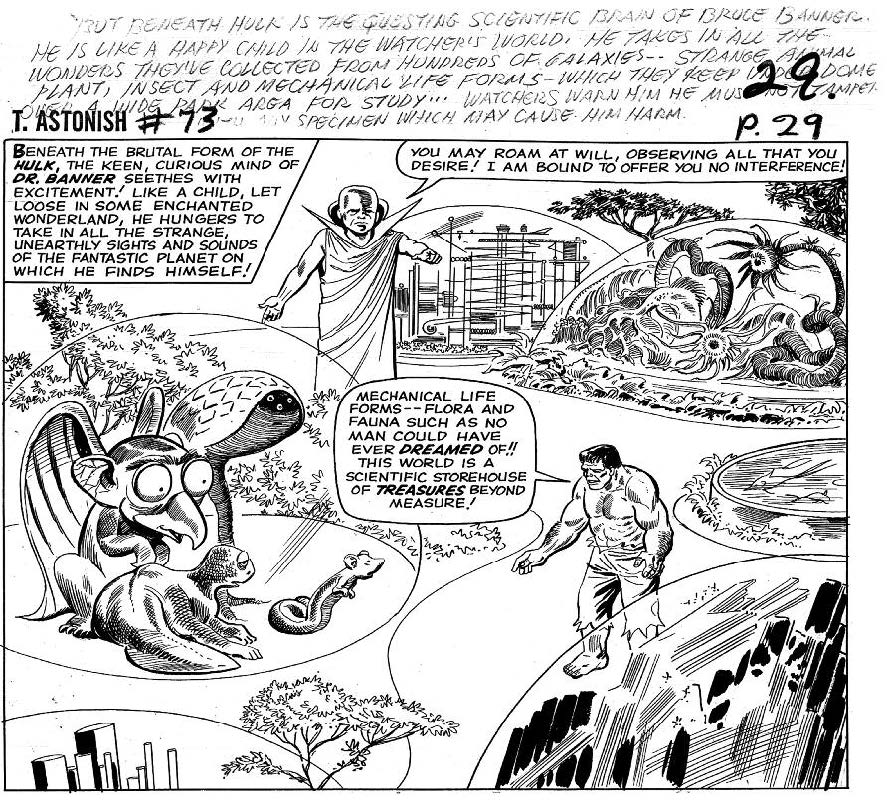

They had nothing for me at that time except those particular strips, which were just going on momentum. So, I began to galvanize those strips and they began to sell a little better, but it wasn’t enough to keep the company going. And it suddenly struck me that the thing that hadn’t been done since the days I returned from the service was the superheroes. And so, I came up with Spider-Man. I got it from a strip called the Silver Spider. And I presented Spider-Man to Stan Lee and I presented the Hulk to Stanley. I did a story called “The Hulk”– a small feature, and it was quite different from the Hulk that we know. But I felt that the Hulk had possibilities, and I took this little character from the small feature and I transformed it into the Hulk that we know today.

Of course, I was experimenting with it. I thought the Hulk might be a good-looking Frankenstein. I felt there’s a Frankenstein in all of us; I’ve seen it demonstrated. And I felt that the Hulk had the elem of truth in it, and anything to me with the element of truth is valid and the reader relates to that. And if you dramatize it, the reader will enjoy it.

Sleaziness and reality, you can walk out in the street anywhere and get that. But to get good, dramatized entertainment was very rare. What I did was. take what I know and dramatize it.

PITTS: So, you’re saying the idea for these characters– the F.F., for instance– was yours?

KIRBY: The idea for the F.F. was my idea. My own anger against radiation. Radiation was the big subject at that time, because we still don’t know what radiation can do to people. It can be beneficial, it can be very harmful. In the case of Ben Grimm, Ben Grimm was a college man, he was a World War II flyer. He was everything that was good in America. And radiation made a monster out of him–made an angry monster out of him, because of his own frustration.

If you had to see yourself in the mirror, and the Thing looked back at you, you’d feel frustrated. Let’s say you’d feel alienated from the rest of the species. Of course, radiation had the effect on all of the F.F.– the girl became invisible, Reed became very plastic. And of course, the Human Torch, which was created by Carl Burgos, was thrown in for good measure, to help the entertainment value.

I began to evolve the F.F. I made the Thing a little pimply at first, and I felt that the pimples were a little ugly, so I changed him to a different pattern and that pattern became more popular, so I kept it that way and the Thing has been that way ever since. The element of truth in the Fantastic Four is the radiation– not the characters. And that’s what people relate to, and that’s what we all fight about today.

PITTS: You think people relate more to the radiation aspect than to the characters?

KIRBY: No… Now, they relate to the characters because time has passed and the characters are important.

PITTS: You say you created Spider-Man. How different was your initial concept from the Spider-Man we all know?

KIRBY: My initial concept was practically the same. But the credit for developing Spider-Man goes to Steve Ditko; he wrote it and he drew it and he refined it. Steve Ditko is a thorough professional. And he an intellect. Personality wise, he’s a bit withdrawn, but there are lots of people like that. But Steve Ditko, despite the fact that he doesn’t disco– although he may now; I haven’t seen him for a long time– Steve developed Spider-Man and made a salable item out of it.

There are many others who take credit for it, but Steve Ditko, it was entirely in his hands. I can tell you that Stan Lee had other duties besides writing Spider-Man or developing Spider-Man or even thinking about it.

PITTS: So, you’re saying you had the original idea and presented it to Ditko?

KIRBY: I didn’t present it to Ditko. I presented everything to Stan Lee. I drew up the costume, I gave him the character and I put it in the hands of Marvel. By giving it to Stan Lee, I put it in the hands of Marvel, because Stan Lee had contact with the publisher. I didn’t. Stan Lee gave it to Steve Ditko because I was doing everything else, until Johnny Romita came in to take up some of the slack. There were very few people up at Marvel; Artie Simek did all the lettering and production.

PITTS: Now, Stan has said many times that he conceived Spider-Man and gave it to you and that he turned down the version you came up with because it was too “heroic” and “larger than life”-looking for what he had in mind.

KIRBY: That’s a contradiction and a blatant untruth.

PITTS: What input, then, did Stan Lee have in creating Spider-Man and these other characters?

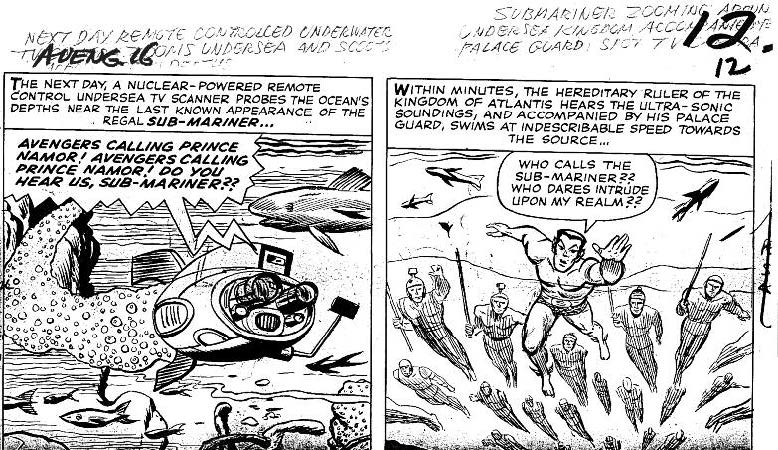

KIRBY: Stan Lee had never created anything up to that moment. And here was Marvel with characters like the Sub-Mariner, which they never used. Stan Lee didn’t create that; that was created by Bill Everett. Stan Lee didn’t create the Human Torch; that was created by Carl Burgos. It was the artists that were creating everything. Stan Lee– I don’t know if he had other duties… or whatever he did there…

ROZ: Maybe we shouldn’t get into… too much characterization. I mean–

KIRBY: What I’m trying to do is give the atmosphere up at Marvel. I’m not trying to attack Stan Lee. I’m not trying to put any onus on Stan Lee. All I’m saying is; Stan Lee was a busy man with other duties who couldn’t possibly have the time to suddenly create all these ideas that he’s said he created. And I can tell you that he never wrote the stories– although he wouldn’t allow us to write the dialogue in the balloons. He didn’t write my stories.

PITTS: You plotted and he did the dialogue?

KIRBY: You can call it plotted. I call it script. I wrote the script and I drew the story. I mean, there was nothing on the first or second page that Stan Lee ever knew would go there. But I knew what would go there. I knew how to begin the story. I wrote it in my house. Nobody was there around to tell me. I worked strictly in my house; I always did. I worked in a small basement in Long Island.

PITTS: Okay, take me through a typical Lee-Kirby comic. Say, from start to finish, an issue of the F.F.

KIRBY: Okay, I’ll give it to you in very short terms: I told Stan Lee what I wrote and what he was gonna get and Stan Lee accepted it, because Stan Lee knew my reputation. By that time, I had created or helped create so many different other features that Stan Lee had infinite confidence in what I was doing.

Actually, we were pretty good friends. I know Stan Lee better than probably any other person. I know Stan Lee as a person… I never was angry with him in any way. He was never angry with me in any way. We went to the cartoonists’ society together.

Watching Marvel grow was beneficial for both our egos. They wanted to discontinue the Hulk after the third issue and the day they wanted to discontinue it, some college fellas came up from either NYU or Columbia– I forget which college it was– and they had a petition of 200 names and they said the Hulk was the mascot of the dormitory. I didn’t realize up to that moment that we had the college crowd.

PITTS: You’re given credit; both you and Stan, for the first “human” heroes. Where did that concept come from?

KIRBY: What do you mean, the first human heroes?

PITTS: The first heroes that argued amongst themselves, the first heroes where the characterization was more or less believable as opposed to the flawless Superman type.

KIRBY: That was my idea. Strictly my idea. I felt that that was the truth. I had done the same thing for DC. I did a thing called Mile-A-Minute Jones where this black American Ranger had met up with this German SS man. They had been in the 1936 Olympics and nobody knew who won their race because it was a draw. In the story, they act like two friends who had met after a period of years when they suddenly realize that they’re on opposite sides and that to complete their mission, one would have to kill the other. And so, they run along this engineer’s tape–and as they chase each other, it becomes the race all over again. And the element of truth is there.

These two men, although they’re enemies, were once friends. Each one is a patriot for their own country (but) they’re still friends in a past-tense. And of course, that’s a contradiction too, and yet here they are with these feelings. The German runs on the wrong aide of the tape and gets blown up. Mile-A-Minute Jones completes his mission and is taken away by airplane but as he looks down and he knows the German is dead down there, lying in the field, he knows he’ll never know who won that race. It’s a dramatic story of mine… I got a lot of response on it, and yet it’s a very real story, because I myself talked to the S.S. men; and they were people.

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] Honey, what he’s trying to point out is the relationships – like the Fantastic Four… they became more humanized, more complex.

KIRBY: Well of course, I did all the stories. I created all the stories.

PITTS: Okay, but where did you get the inspiration to do–

KIRBY: Because I wanted to do a satire of Stan and I getting thrown out of a wedding, so I got Reed and Sue married. I love satire. I did Fighting American and had a wonderful time with it. So I felt, Stan Lee and I were good friends, it would be·fun to have us thrown out of a wedding.

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] But even at the beginning, you had the Fantastic Four, they were always arguing about–

KIRBY: Yeah. The Thing had problems…

PITTS: Johnny was immature, Reed was a stuffed shirt–

KIRBY: Yes. They were people to me. I write from a people’s point of view. I love people because I understand them. I understand an enemy, I understand a friend, I understand grey areas, and I understand black areas. I understand when it’s you or me and I understand when it’s you and me. I’m a fellow who was raised in that kind of atmosphere, and it will reflect in the kinds of stories that I write.

PITTS: Are there any other Marvel flagship characters that you feel you created and didn’t get the credit for?

KIRBY: Yes, I created the Young Allies.

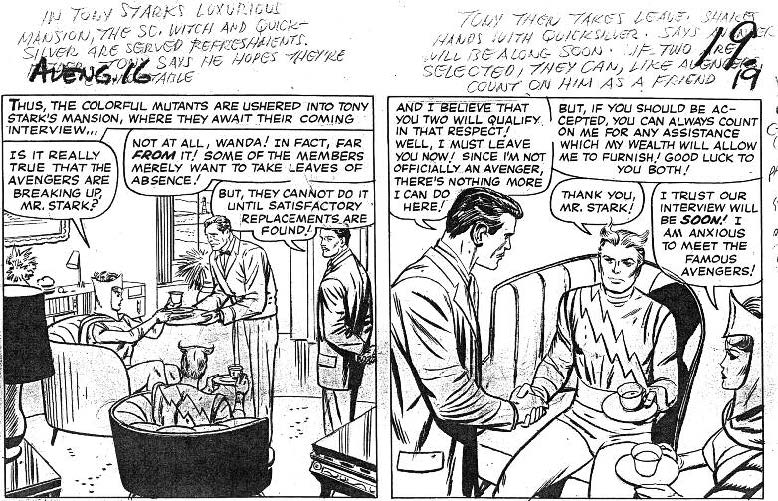

PITTS: No, I’m talking about the Marvel Age heroes… the X-Men, the Avengers…

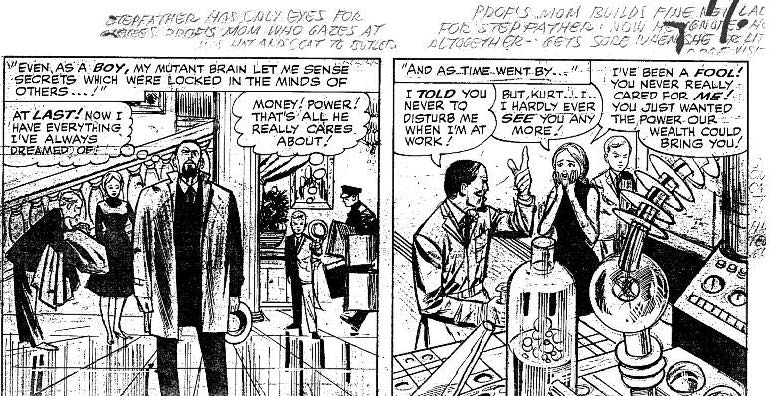

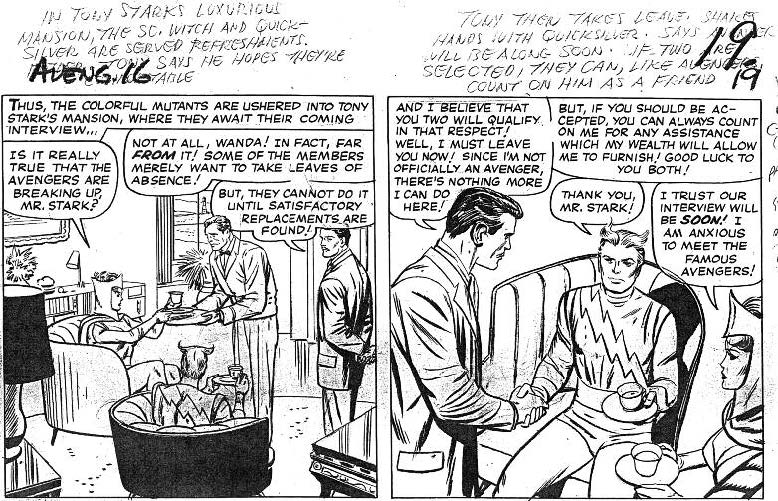

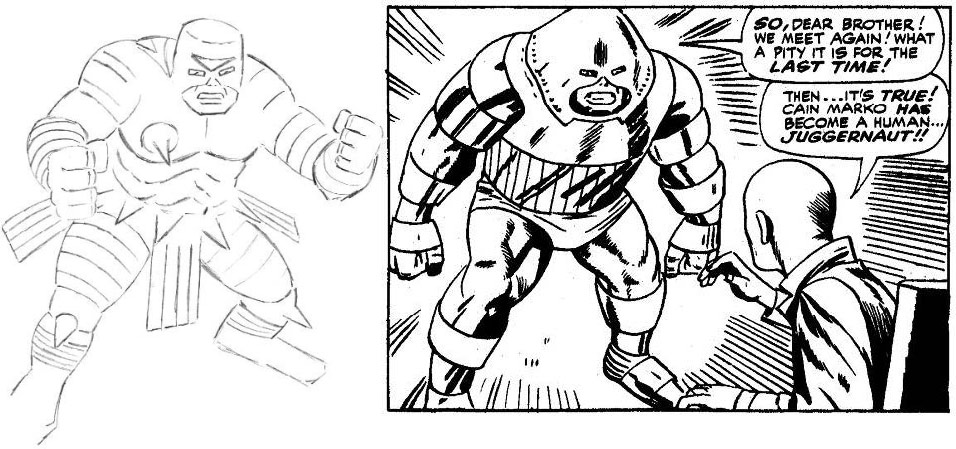

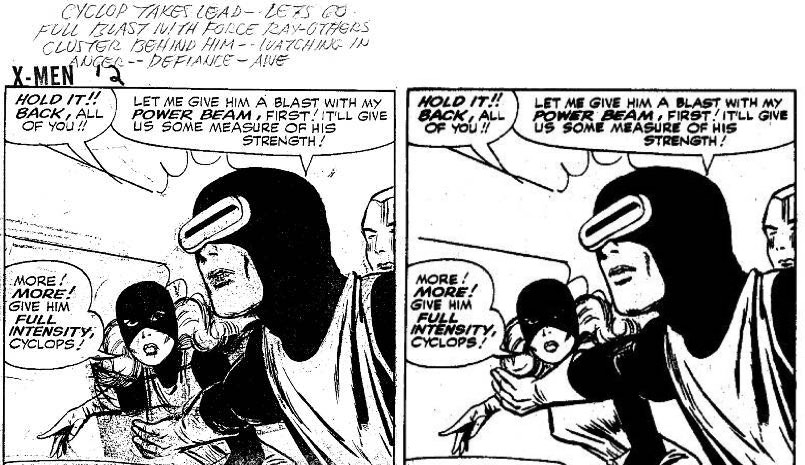

KIRBY: All of them. All of them came from my basement. The Avengers, Daredevil, the X-Men… all of them. The X-Men, I did the natural thing there. What would you do with mutants who were just plain boys and girls and certainly not dangerous? You school them. You develop their skills. So I gave them a teacher, Professor X.

Of course, it was the natural thing to do, instead of disorienting or alienating people who were different from us, I made the X-Men part of the human race, which they were. Possibly, radiation, if it is beneficial, may create mutants that’ll save us instead of doing us harm. I felt that if we train the mutants our way, they’ll help us– and not only help us, but achieve a measure of growth in their own sense. And so, we could all live together.

PITTS: You obviously feel that you haven’t gotten the credit that’s due you for the contributions you’ve made. How does that fact set with you?

KIRBY: Well, it’s painful. They’ve kept my pages from me. I have people coming up who want pages signed… a little boy’ll come up with a page of mine that I know is stolen art and I haven’t got the heart not to sign it, so I sign it.

ROZ: What’s painful is that he’s never received his due after helping create Marvel.

PITTS: Yes, that’s what I’m trying to get at.

KIRBY: I’m not interested in the ego trip of creating or not creating. I’m interested in selling a magazine. Rock-bottom, I sell magazines. I’m a thorough professional who does his job. In the Army, I remember, Stan Lee was in the photographic division. They gave him a whole movie studio– this is the story he told me. And Stan Lee didn’t produce one picture. I would’ve produced five. It’s the will to create that tells the truth.

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] What he’s trying to bring out is… we are hurt about how Marvel treated you.

KIRBY: Well, yes, I am hurt because up at Marvel, I’m a non-person. They say Stan Lee created everything. And of course, Stan Lee didn’t. And Ditko is hurt; Ditko never got his due. The fellas who did make all the sales for the magazines were never given credit for them. They were abused in one way or another. I can tell you that that’s painful. You live with that. You live with that all your life. I have to live with the fact of all those lies, which are being done for pure hype.

The people at Marvel (now) weren’t there at that period. The new kids weren’t there. The new kids didn’t feel that desperation– never felt any desperation. In a way, they don’t care. Why should they? They have their lives ahead of them. Nobody will get involved or go on crusades. “Truth, justice and the American way” is just a childish slogan to a lot of people. But I can tell you that a lot of guys died for it. Superman created an attitude that helped many Americans in a very bad spot.

PITTS: If you were that unhappy with Marvel, why did you stay there until over 8 years after the creation of the F.F.?

ROZ: During the time with Marvel, the Fantastic Four, he was making a living. He was building a family, making a living. There weren’t too many places to go in comic books.

KIRBY: Right. And there still isn’t too many places to go. And I had gotten too used to liking to work alone. I don’t like to work in an office. I like to work in my house, to be among my own thoughts. The idea is for an editor to let his artist alone, let them be themselves– an artist or a writer– let them alone, let them exchange their own ideas and you’ll come up with something salable.

PITTS: Why did you leave the F.F. and Marvel that first time?

KIRBY: Because I could see things changing and I could see that Stan Lee was going in directions that I couldn’t. I came in one night and there was Stan Lee talking into a recording machine, sitting in the dark there. It was strange to me and I felt that we were going in different directions.

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] Well, you also wanted to go on to new situations. That’s why–

KIRBY: I wanted to do the same thing I had always done– just sell magazines and create my own ideas. The first thing I did when I got to DC was create the comic novel. The first comic novel was mine. That’s the New Gods. I took four magazines to make an entire novel.

They wanted me to work with Superman, but I didn’t want to interfere with the work that was being done by the other men. I felt I could create my own novel. I love the young people, so I did the Forever People. I had a good planet and an evil planet… a parable on our own society.

Darkseid is a man you will never see; Darkseid runs our world. High Father runs our world. These two men run our world; you’ll never see who they are. I put them together in two individuals. A part of our society runs this world and they run it for good or evil. The evil side will harm us, the good side of it will help us. So far, we’ve been skirting in the middle and making out.

PITTS: Okay, you mentioned earlier walking into an office and seeing Stan talking into a recorder one night and I got the impression that was some sort of turning point for you–

KIRBY: Well, I realized I was creating something I didn’t want to create.

PITTS: But, how did–

KIRBY: Did you ever read “What Makes Sammy Run” by Budd Schulberg?

PITTS: No.

KIRBY: Read “What Makes Sammy Run”. Sammy, in that book, is the kind of a character you wouldn’t want to be responsible for developing. I felt that I was developing a Sammy– which I was, in Stan Lee. I felt it was my time to go.

PITTS: You’re very cryptic, Mr. Kirby.

KIRBY: Well, I feel I can only be responsible to the company in a business sort of way, never in a personal sort of way. And incidentally, they’ve looked on it differently. I can tell you that, besides being a non-person up there, I’ve had adverse personal incidents… which I won’t tell you about. And they’ve hurt me badly.

It’s something you don’t like to live with. If I cut off your arm, you’re going to live with that forever. Even if they put a false arm on you, you’re never going to have a right or left arm. And that’s what they’ve done to me. They’ve cut off one of my limbs. Keeping my pages… spreading lies. Blatant lies.

They just advertised the fact that Stan Lee created Captain America. This was in Variety. And it said, “Based on a character created by Stan Lee”. Stan Lee didn’t create Captain America.

PITTS: That has to be a mistake.

KIRBY: We’ll show you the ad.

PITTS: Somebody goofed somewhere. I mean, that one is already on the record books as a Kirby-Simon creation.

KIRBY: No.

PITTS: Let’s talk about some of the later creations–again, the story behind the story. Let’s begin with the New Gods.

KIRBY: The New Gods went into my feelings about the world around me. There’s an element of truth in that. The fact that Darkseid exchanged sons with High Father– that’s taken from history. Kings in the past have exchanged sons so that they never have wars in the future, lest they harm these children. A father will not harm his son.

PITTS: The Forever People.

KIRBY: The Forever People were the wonderful people of the ’60s, who I loved. If you’ll watch the actions of the Forever People, you’ll see the reflection of the ’60s in their attitudes, in the backgrounds, in their clothes. You’ll see the ’60s. I felt I would leave a record of the ’60s in their adventures.

PITTS: The Eternals.

KIRBY: The Eternals? The Eternals are the gap that we can’t fill. We don’t know what happened back in the Biblical days. We’ve killed a lot of people because of it, but we don’t know what happened back then. Did Jonah blow down Jericho with 40 trumpets? I’d like to see someone do it. I feel that, from time to time, mankind has risen and destroyed itself and left something for the survivors…

PITTS: What do you think of the current state of comics, as opposed to what it was in your heyday?

KIRBY: I really can’t say. I wish the artists well, I wish the publishers well. It’s an industry that’s given me a good life.

PITTS: But, how do you like the books?

KIRBY: The books? They’re different from the kind of books that we did. I find a little less discipline, a little more illustration. They’re filling up the panels so the eye can’t focus on certain characters. If you go in a New Year’s crowd in New York, you won’t be able to focus on anything, except that ball in the tower, because there’ll be so many people there that you wouldn’t be able to concentrate on anything.

PITTS: So, are you saying that the quality of the artwork in comics has deteriorated?

KIRBY: A crowd is faceless. If you put a hero among a crowd, he won’t stand out. He’ll become part of the crowd.

PITTS: Do you read many books?

KIRBY: No I don’t. I used to read a lot of books. I read what’s important me. I’ll read a lot of scientific articles– not a lot of comics. I get a lot of comics, and I can look at a comic and tell immediately whether I’ll enjoy it or not. I’ve had 50 years of doing that.

There are elements in the stories now that I have no rapport with. I see dirty language, I see sleazy backgrounds; I see it reflected in the movies– the movies are comics to me. And I don’t see a sleazy world. I see hope. I see a positive world.

PITTS: Do you read your own characters– the current versions?

KIRBY: Yes I do, because I feel my characters are valid, my characters are people, my characters have hope. Hope is the thing that’ll take us through.

PITTS: Okay, when I say your characters, I’m referring to the ones you created at Marvel in the ’60s.

KIRBY: No. I’m not interested in their version. It has nothing to do with me.

PITTS: With every artist you talk to, if you ask them who their biggest influence is, the name Kirby will be at or very near the top of the list. How does it feel to be so revered by a generation of comics artists?

KIRBY: Well… I wouldn’t consider myself in that light. I feel that every professional is the art school for the next guy. In other words, in my early days, I would cannibalize the shading done by Milton Caniff. I would cannibalize the natural stance of Alex Raymond’s figures, because I felt that’s how people stood, that’s how people gestured.

And of course, I feel that maybe a lot of the dynamism in my own work, having been felt by the rest of the artists, they’ll react to it and put elements of that in their own work, feeling that it’ll help it.

PITTS: Are there any of today’s artists that you’re particularly impressed by?

KIRBY: Well, I’m impressed with the character of Frank Miller, who I feel is a very gutsy and intelligent guy. Frankly, I’m biased in that direction because he seems to feel that I’m right in my demands from Marvel. He sympathizes. He feels that in some way maybe I’ve helped him to make a better deal.

PITTS: What do you think of Byrne?

KIRBY: Byrne, I… I feel that any man that tries, any man that comes out with something we like, is a good man. A man doesn’t have to be Leonardo Da Vinci to be sincere. Everybody can draw, in my estimation. If you give a man 50 years, he’ll come up with the Mona Lisa.

PITTS: What makes you so good?

KIRBY: The willingness to compete. I want to be better than five guys. I was that way when I used to box, I was that way in any sport. I want to compete with five other guys. If I beat five other guys, I’d like to see if I can beat six.

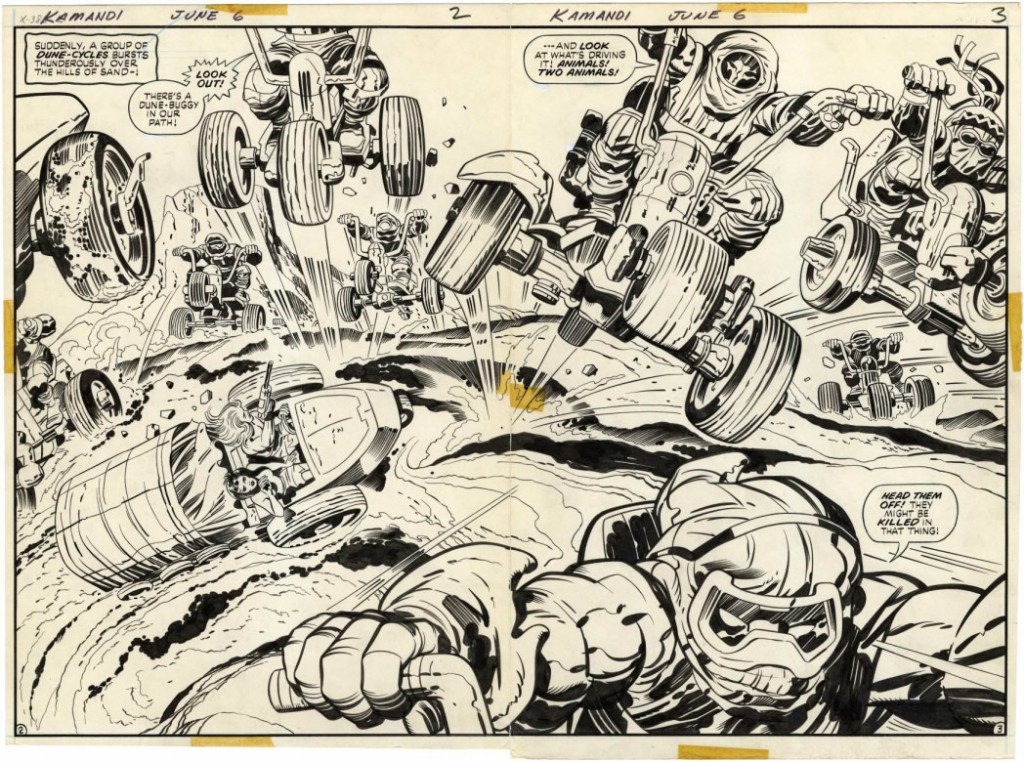

PITTS: There’s not a lot of subtlety in your work. I think that’s what many people have gravitated toward. Everything is larger than life. I remember one artist– I forget which one– talking about how he and everybody else has copied the way in which you draw a punch. It’s where the legs are slightly wider apart in the stance, and there’s more body behind the blow– a real power punch. Where does this larger-than-life outlook come from? When I met you, I was expecting to see a man 7 feet tall.

KIRBY: On the contrary, it’ll come from a man who’s 5′ 6″, 5′ 7″ and has to fight a man 7 feet tall. And of course, he knows he’s gonna get creamed, so he dramatizes his own strength and in dramatizing his own strength, he becomes a lot stronger than he really is.

I’ve bent steel. I’ve done things that I wouldn’t ordinarily seem capable of doing. And I’ve proven myself in situations where there’s life and death at stake. And so, I can live with myself knowing that it’s not a matter of guts or anything like that. It’s a matter of willingness to go the length– to transcend yourself.

PITTS: Do you see life itself in larger-than-life terms?

KIRBY: Yes, I do. I feel that man can transcend himself to a point where he can accomplish greater things than he thinks. I see people depressed and I see people who devalue themselves and I feel that’s a terrible, terrible waste. But I love the people who try. But try fairly, try honestly.

PITTS: Which one of your characters is most like you? I’ve got suspicions of my own, but I’d like to hear what you say.

KIRBY: Oh, I feel that they all have some part of my character. I feel that they’re all me in some way– certainly not in individuality, but they all bear elements of what I feel.

PITTS: You don’t think Ben Grimm’s a little more like you?

KIRBY: (laugh) Yes, everybody I’ve talked to has compared me to Ben Grimm and perhaps I’ve got his temperament, I’ve got his stubbornness, probably, and I suppose if I had his strength, I’d be conservative with it. Ben Grimm is that way. Ben Grimm has always been conservative with his strength. You’ll find that, actually, he’s the original Rambo. If he uses his strength, he’ll use it in a justifiable manner– to save somebody, or to help somebody, or to see that fairness grows and evolves and helps people.

PITTS: Where do you see this medium headed?

KIRBY: I have some ideas, but I wouldn’t like to express them. I’ll save it for my novel.

PITTS: Okay, let’s put it like this, then: in the best of all possible worlds for Jack Kirby, what would be different?

ROZ: He’d be a better businessman.

KIRBY: I would’ve liked to have been a better businessman when I was younger. And of course, I couldn’t, because it wasn’t part of my atmosphere. I never lived with accountants, I never lived with lawyers, I never sued anybody, I never fought anybody or was in conflict or contention with any other party in a legal way. I feel that it hurts people, it hurts their families.

My family’s hurt. It’s not that I consider myself; I’ve been hurt in the past many times, but I never consider myself. My wife is hurt, I know other members of my family will be hurt, and I feel that’s wrong.

PITTS: It’s quite a stupid question, in light of all you’ve said, but let me ask it anyway: can you see yourself working with Stan Lee ever again?

KIRBY: No. No. It’ll never happen. No more than I would work with the S.S. Stan Lee is what he is. I’m not going to change him, I’m not going to dehumanize him, I’m not going to default him. He has his own dreams and he has his own way of getting them. I have my own dreams but I get them my own way. We’re two different people. I feel that he’s in direct opposition to me.

There’s no way I could reach the S.S.. I tried to reach them. I used to talk with them and say, “Hey, fellas, you don’t believe in all this horseshit.” And they said, “Oh, yes, we do.” They were profound beliefs. They became indoctrinated.

And Stan Lee’s the same way. He’s indoctrinated one way and he’s gonna live that way. He’s gonna benefit from it in some ways and I think he’ll lose in others. But he doesn’t have to believe me. Nobody else’ll believe me if they don’t want to, but that’s my opinion. I can only speak for myself.

PITTS: Are you claiming that ego has run away with him?

KIRBY: Not ego. Oh, there’s ego in it, but he’s running away from some deep pain or hurt and I don’t know what it is. I feel sympathy for him in that respect. I have an idea of what it is, but it’s not my right to analyze Stan Lee.

If be wants to lionize himself or if he wants others to lionize him or if be feels a lack of something, it’s a problem.

PITTS: I’m almost done. Is there anything you’d like to add to what we’ve already discussed?

KIRBY: No. The only thing I can add is that I’ve been telling the truth and I’ll never speak to another person without telling the truth. I’ve been a cruel man in my time, I’ve been a devious man in my time, like everybody else. I’ve told lies in my time. But I’ve seen enough suffering to experiment with the truth.

Since I’ve matured, since the war itself–I’ve always been a feisty guy, but since the war itself, there are people that I didn’t like, but I saw them suffer and it changed me. I promised myself that I would never tell a lie, never hurt another human being, and I would try to make the world as positive as I could.

There’s a lot of guys that might feel (laughter)… My own son feels I’m uncool but my grandson loves me. Being cool or uncool is a generational thing. But as a personal thing, I really love everybody in sight. I’d love to see Stan Lee at peace with himself. I mean, really at peace with himself. Not money-wise, not ambition-wise, not being driven–whatever drives him. But I’d like to see him at peace as a human being.

PITTS: If I asked you for one word to describe Jack Kirby, what would that word be?

KIRBY: Human being.

PITTS: That’s two words.

KIRBY: Human. Okay?