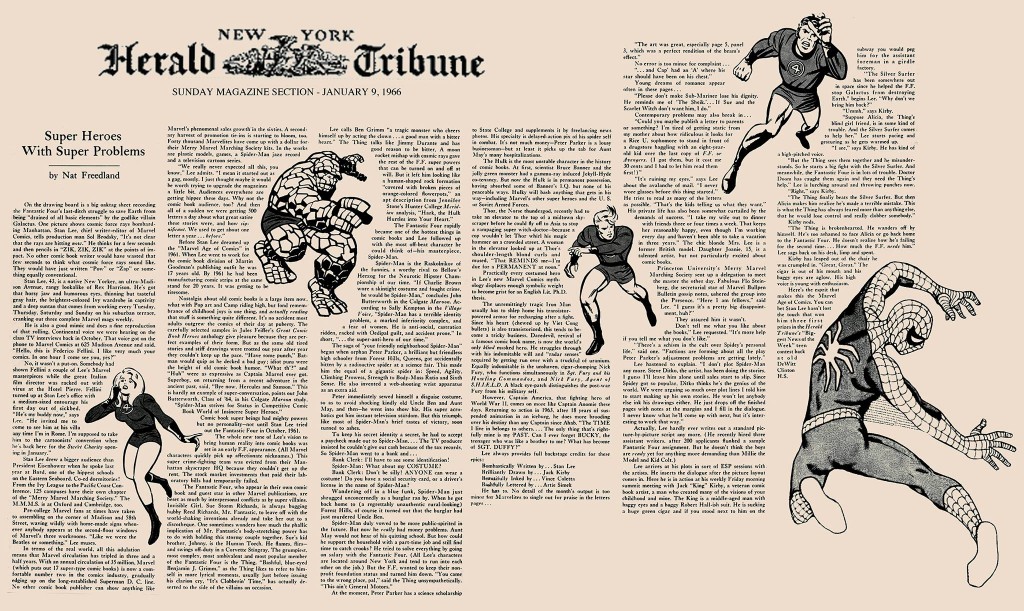

Michael Hill sent us this article, as well the Interviews piece we published in June, for consideration for The Kirby Effect. We’re publishing it here in 3 parts with comments disabled – Rand Hoppe. With thanks to Steven Brower.

Articles in this series:

* Interviews

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part one

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part two

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part three (you are here!)

Lee the Creator

Tom Crippen: 1

People compare Lee-Kirby and Lennon-McCartney. I think that misses the point. It was more like Jimi Hendrix was in a band with whoever did the words for “Incense and Peppermints.” Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko (the label’s Syd Barrett, I guess) had talent. Lee had knacks: for putting words on pictures, for peanut gallery banter, for gimmicky ear prodding, verbal drumrolls, the hey-gang tone, mock grandiosity… Now he makes a handsome living as an icon while pretending to be a creator. Being Stan Lee means saying the artists do the pictures first and then you put on the balloons, and your wife said to you why not do a story you want to do, and Kirby was the best, a splendid imagination, and comics do a lot for getting young people to read.

From Neal Kirby’s deposition: 2

FLEISCHER Do you have any basis to contradict Mr. Lee’s testimony that the concept for the Iron Man character was his?

A Do I have any basis for that? I have the basis that I know my father’s creativity versus Mr. Lee’s creativity and Mr. Lee was an excellent marketer, he was an excellent manager, excellent self-promoter. I honestly don’t believe he had any creative ability.

Q Do you feel that Mr. Lee’s testimony in some way diminished the contribution that your father made to the various characters that he worked on at Marvel?

A Diminished I think is – I think diminished is the least of it. I think Stan Lee is kind of rewriting history…

Steve Ditko: 3

Such is the power of a prestigious public spotlight and blind faith.

Stan Taylor: 4

Stan Lee says “all the concepts were mine” (Village Voice, Vol.32 #49, Dec. 1987). It is his contention that he singly produced a script [for Spider-Man], offered it to Jack Kirby, and when he didn’t like the look of Kirby’s rendition, he then offered it to Steve Ditko. Can he be believed? Not really. Stan would go so far (or stoop so low!) as to claim that a minor character named The Living Eraser from Tales to Astonish #49 was his creation. This character, had the dubious distinction of being able to wave people out of existence with a swipe of his hand. “I got a big kick out of it when I dreamed up that idea,” Lee is quoted as saying (Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics, pg. 97). He then further embellishes this tale by stating how hard it was to come up with an explanation for this power. The fact is, this ignoble power and explanation, first appear in a Jack Kirby story from Black Cat Mystic #59 (Harvey Publications, Sept. 1957). If Lee will take credit for an obvious minor Kirby creation such as The Living Eraser, which nobody cares about, then he certainly would take credit for another’s creation that has become the company’s cash cow.

Daniel Keyes, author of Flowers for Algernon (between 1952 and 1955 Keyes was a prolific contributor to Stan Lee’s fantasy/horror line): 5

MURRAY: Stan Lee is today considered one of the great comic book writers. Was he writing many comics in those days?

KEYES: Not to my knowledge. He edited, I guess. He was a businessman, as far as I was concerned. And a shy businessman is almost an oxymoron. I’ve never thought of Stan as a writer at all. So that surprises me. Of course, he might have been turning in comics for a few extra bucks, doing it under pen names so that Martin Goodman wouldn’t know about it. I never thought of Stan as a writer. He says that he created Spider-Man. I never thought of him as a creative person. It could be that one of the writers created it and sent in a synopsis. And it got picked up. But of course he’s become a multi-millionaire for that stuff.

Richard Kyle: 6

By the way, in discussing just what Jack did and what Stan did, no one seems to refer to that SHIELD story in Strange Tales #148, mentioned by the San Diego panel in another connection. In an editorial, Lee mentions specifically that Jack was going to write the story while Stan took a vacation. I recall turning to the story, wondering if it would be different from the regular SHIELD yarns, and being a little surprised that it read the same as the others—which I had believed Lee wrote. Consequently, I wasn’t surprised when Lee’s attempts to write the FF after Jack left were not only poor but completely unlike any of the Fantastic Four stories done under Jack. By that time, I realized that Lee was simply a dialogue writer, not a story writer—much like the “title-writers” in silent movies, many of whom were extremely talented (and often touched with genius) and highly paid, but whose work was after the fact of the actual creation of the story and filming.

1989 [Groth] 7

KIRBY: Stan was a very rigid type. At least, he is to me. That’s how I sized him up. He’s a very rigid type, and he gets what he wants when the advantage is his. He’s the kind of a guy who will play the advantages. When the advantage isn’t his at all, he’ll lose. He’ll lose with any creative guy. And I could never see Stan Lee as being creative. The only thing he ever knew was he’d say this word “Excelsior!”

Lee’s Inspiration

[see the “Interviews” post for Kirby’s Inspiration]

Thor

From Origins: 8

The only one who could top the heroes we already had would be Super-God, but I didn’t think the world was quite ready for that concept yet. So it was back to the ol’ drawing board.

I must have gone through a dozen pencils and a thousand sheets of paper in the days that followed, making notes and sketches, listing names and titles, and jotting down every type of superpower I could think of. But I kept coming back to the same ludicrous idea: the only way to top the others would be with Super-God.

As far as I can remember, Norse mythology always turned me on. There was something about those mighty, horn-helmeted Vikings and their tales of Valhalla, of Ragnarok, of the Aesir, the Fire Demons, and immortal, eternal Asgard, home of the gods. If ever there was a rich lode of material into which Marvel might dip, it was there—and we would mine it.

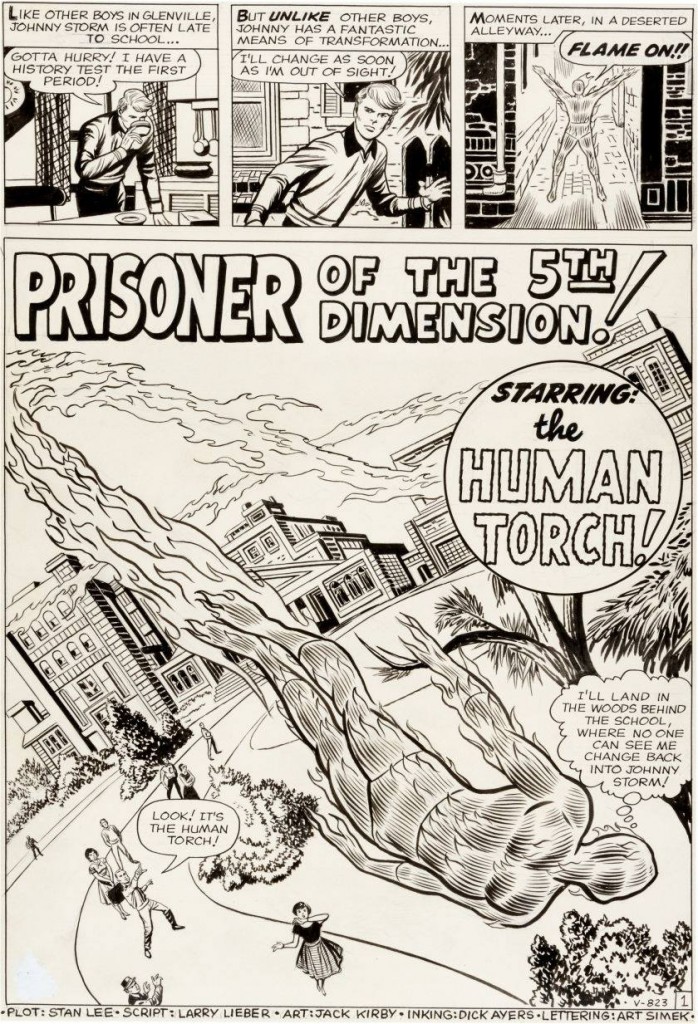

Historians of the future will wish to note that Larry Lieber acquiesced when asked if he’d pen a new superhero strip for the greater glory of Marveldom. Let the record also show that Jack Kirby did likewise when offered the illustrating chore.

Assorted characters

From Stan Lee’s depositions [emphasis mine]: 9

QUINN: Tell me to the best you can recall, how did the idea for the Fantastic Four come about, and who they were, and what was the back story with regard to the Fantastic Four.

A. Well, as I mentioned, Martin Goodman asked me to create a group of heroes because he found out that National Comics had a group that was selling well. So I went home, and I thought about it, and I – I wanted to make these different than the average comic book heroes.

Q. Let’s talk a little bit about the Spider-Man. How did the idea for Spider-Man come about?

A. Again, I was looking for – Martin said, “We’re doing pretty good. Let’s get some more characters.” So I was trying to think of something different.

Q. And could you tell us how The Incredible Hulk came about? What was your idea for him?

A. Well, same thing. I was trying to – it was my job to come up with new characters and to expand the line as much as I could. So I was trying to think again what can I do that’s different.

Q. Tell us about how Iron Man came about, how he was created, the back story with regard to Iron Man.

A. I will try to make it shorter. It was the same type of thing. I was looking for somebody new.

Q. And how Thor was created and what was your idea behind Thor.

A. Same thing. I was looking for something different and bigger than anything else.

Q. Daredevil. I want to hear about the lawyer.

A. Again I’m trying to think of what can I do that hasn’t been done. And it occurred to me –

Q. Keeping with our discussion, could you tell us about the creation of X-Men? How did that come about?

A. Again, Martin asked me for another team because the Fantastic Four had been doing well. And again I wanted to try something different.

Q. Who created Ant-Man?

A. What could I do that was different?

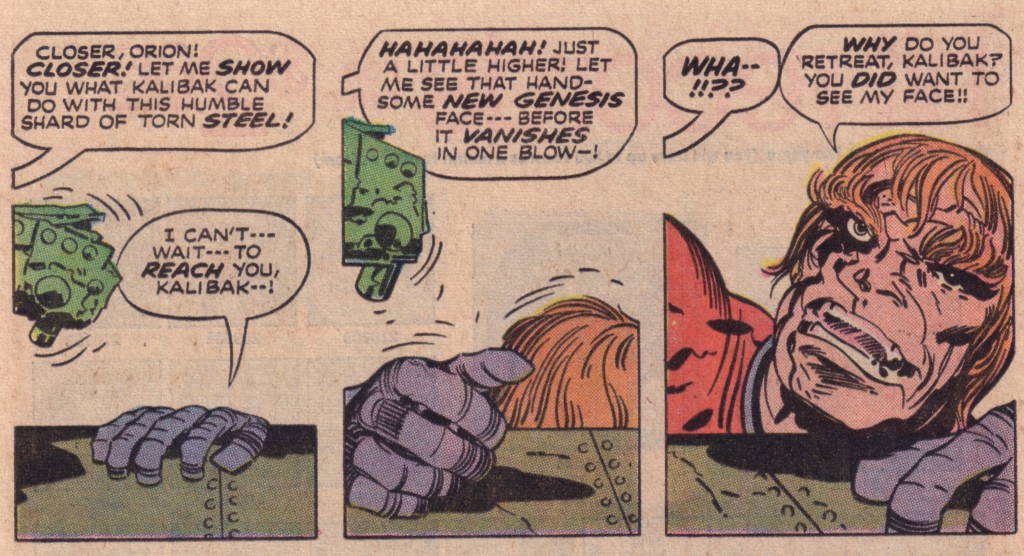

Nick Fury

From Lee’s depositions: 10

Q. Next Nick Fury. Tell us about Nick Fury.

A. Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. There was a television series called The Man from U.N.C.L.E. that I used to watch and I liked it. And I thought it would be fun to get something like that as a comic book.

So I remembered we had done a war series called Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos, Stories of World War II. And it was quite popular. I don’t really like war stories, so after a few years of doing it I asked Martin if we could drop the book so we could concentrate on superheroes. And he said okay. But we got a lot of fan mail. The kids loved the characters. And we kept reprinting those books, and they sold as well as the originals.

So when I wanted to do the thing like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., I thought why don’t I take that popular Sgt. fury that was years ago in World War II, why don’t I say he’s older now and he’s a colonel, and he’s in charge of this new outfit that I made up, S.H.I.E.L.D, which stood for the Supreme Headquarters International Law Enforcement Division. So I took Sgt. Fury, who now has a patch over one eye, and made him in charge of this group.

And again, there was Jack Kirby. I said, “How would you like to draw Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. And it was right up Jack’s alley. He loves that kind of stuff. And he came up with all kind of weapons and things.

As of May 2015, the official version of Nick Fury’s creation differs from Lee’s sworn testimony. Marvel Executive Editor Tom Brevoort, quoted on Marvel’s website: 11

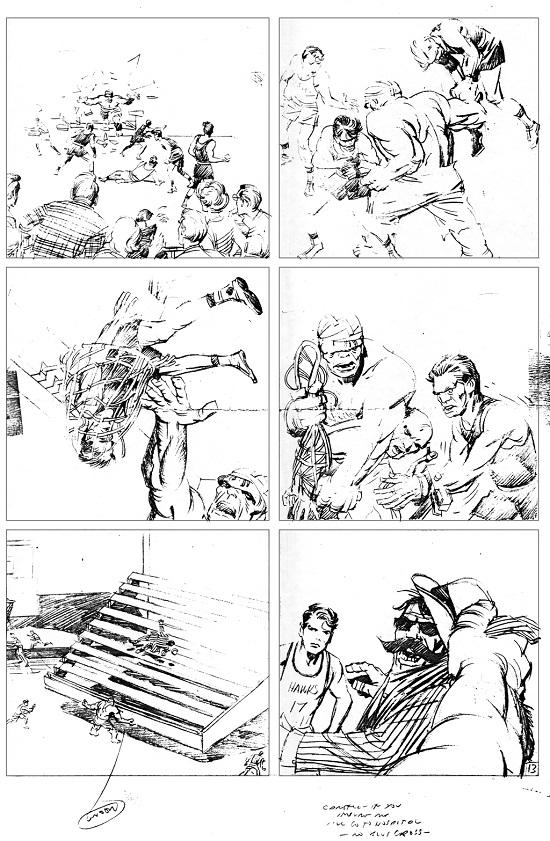

“Jack Kirby first broached the idea of doing a modern day strip with Nick Fury, and he produced a two-page ‘pilot sequence’ to show to Stan Lee, titled ‘The Man Called D.E.A.T.H.,’” he says. “Stan liked the idea of a modern day Fury strip, but reworked the basic concept with Kirby to create NICK FURY, AGENT OF S.H.I.E.L.D. And that two-page pilot story was never used. In fact, when Jim Steranko turned up at Marvel looking for work, Stan gave it to him as an inking test, which is why those pages are inked by Steranko.”

Kirby the Creator

Joe Sinnott: 12

I got to know Jack Kirby’s work and remarkable creativity quite well and witnessed his characters and stories as they evolved. There is no question in my mind that Jack Kirby was the driving creative force behind most of Marvel’s top characters today including “The Fantastic Four,” “The Mighty Thor,” “The Incredible Hulk,” “X-Men” and “The Avengers.” The prolific Kirby was literally bursting with ideas and these characters and stories have all the markings of his fertile and eclectic imagination.

Jim Woodring: 13

He was like a wild spraying geyser of the substance we struggled pitifully to evoke in driblets. Even those among us who had never read superhero comics and saw Jack without his aura, so to speak, stood in awe of him. He was more than a master; he was the comic book impulse incarnate.

We loved to draw him out in conversation because he was completely unpredictable; his mind was nimble and unfettered by convention. I never heard him tell an anecdote that was not heavily spiced with benign absurdity. As with his drawing, there was something preciously fragile about his sledgehammer approach to storytelling. One sensed that a hard life had made Jack tough, but that the great child’s heart of which he was the custodian had been sheltered and saved at all costs, and that this heart was the force that drove him.

Jim Steranko: 14

More than anyone around him, Kirby was aware of the magnitude of his contributions, yet he never evidenced a moment of public arrogance or conceit.

From Neal Kirby’s deposition: 15

FLEISCHER Of your own firsthand knowledge do you know whether the concept for the Spider-Man character and the basic powers of a Spider-Man character were conceptualized initially by Stan Lee or someone else?

A Well, I would say my firsthand knowledge, my first guess would be my father just because of his – just his knowledge of science, his use of science fiction in stories, just in his if you want to call it pattern, for lack of a better word, of how do you get a human to have super powers, you know, without direct intervention from God. Well, the best way to do it was somehow altering DNA which was the big thing at the time with the Cold War going on and so on.

Q Did your father ever tell you that he was the sole creative force at Marvel during his tenure there?

A I don’t recall him using – again, my father would have been too humble a person to even word anything like that but I know in discussions it just, to me, he certainly seemed that way.

Q What information, if any, do you have concerning the creation of The Fantastic Four?

A In discussions with my father The Fantastic Four basically was a derivative of the, from what he told me, basically he came up with the idea just as a derivative from the Challengers of the Unknown that he had done several years earlier.

Q Apart from the specific instance that you recall with respect to Fantastic Four, can you recall the specifics of any of those instances where your father relayed to you statements made to him or others by Stan Lee that were the subject of concern to your father?

A I can remember one instance, again I do not recall if it was a print interview or, you know, on-the-air interview or what it might have been, but I do recall one instance involving the creation of Thor and I guess Stan had taken – he had created that and my father was very upset about that. He said Thor was his idea, his creation. Honestly, given my father’s interest in mythology and Norse mythology and, again, biblical history and all kind of history, that kind of thing just flowed out of his mind. I mean, to me just from my knowledge of comic history, and I’m not a comic historian by any means, but my knowledge of it and my personal history, the thought of Stan Lee, honestly, coming up with concepts of, you know, Thor, Loki and Ragnarok, The Rainbow Bridge and every other part of Norse mythology coming out of Stan Lee’s mind is relatively inconceivable.

Stan Goldberg (interview with Jim Amash): 16

Jack would sit there at lunch and tell us all these great ideas about what he was going to do next. It was like the ideas were bursting from every pore of his body. It was very fascinating because he was a fountain of ideas.

Ken Viola: 17

When I first began the journey to make my 1987 film The Masters of Comic Book Art, I had no idea it would end up being about The Storyteller — artists who both drew and wrote. It is the supreme challenge of the artist and their ability to tell the story — to break it down visually, in terms of content, time, space, action, emotion, reflection… et al. The accomplishment of that goal is to take the personal and private experience of the artist and give it to the reader. To then be able to communicate that same spark of life to the masses is the rarest of gifts. That achievement is Jack Kirby’s life’s work.

Stan Taylor: 18

Jack Kirby was a conceptualist, an idea man, he felt that creation was the coming up of new ideas.

Michael Vassallo: 19

Only Kirby could have launched the Marvel universe because all the concepts came from him.

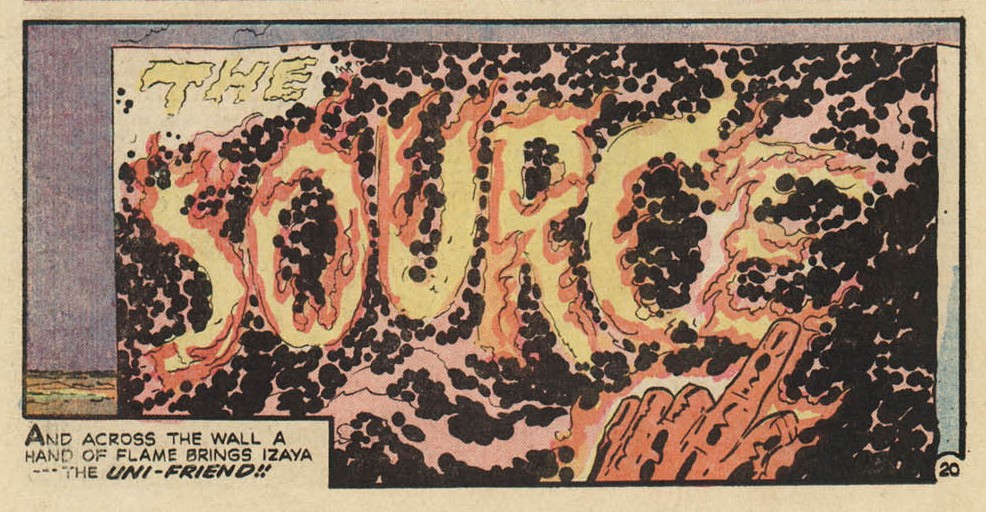

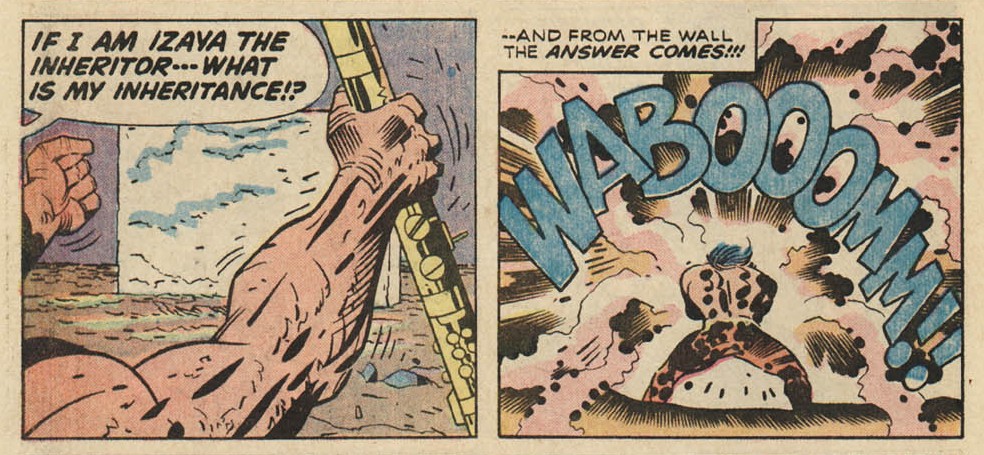

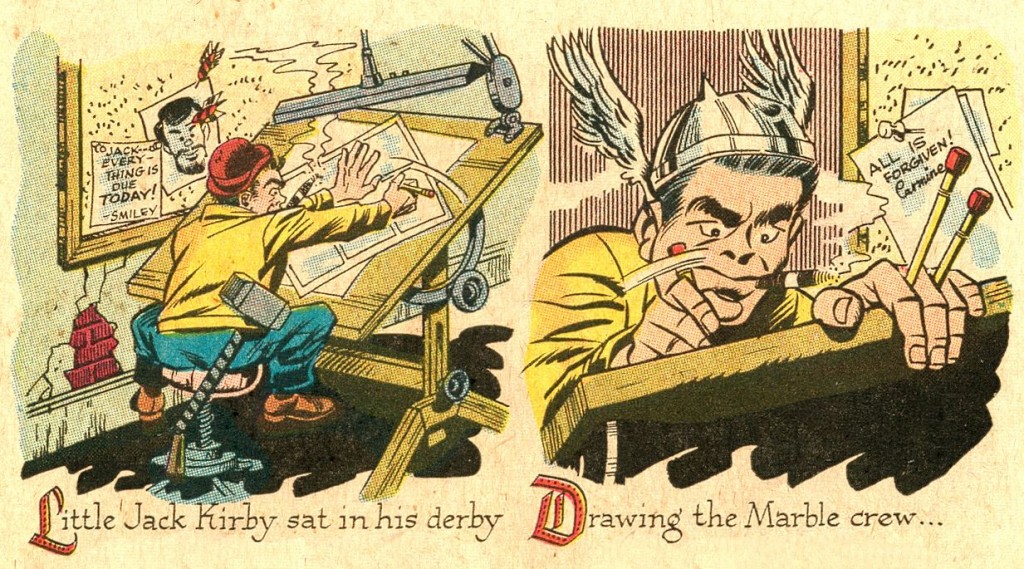

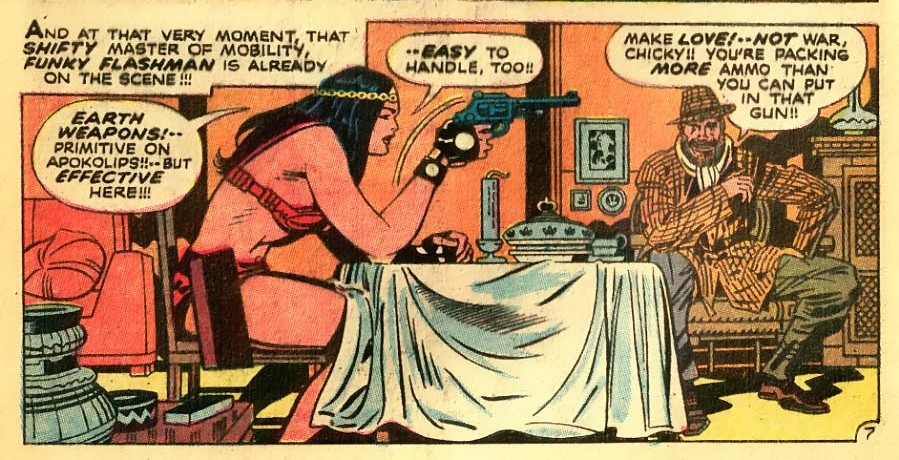

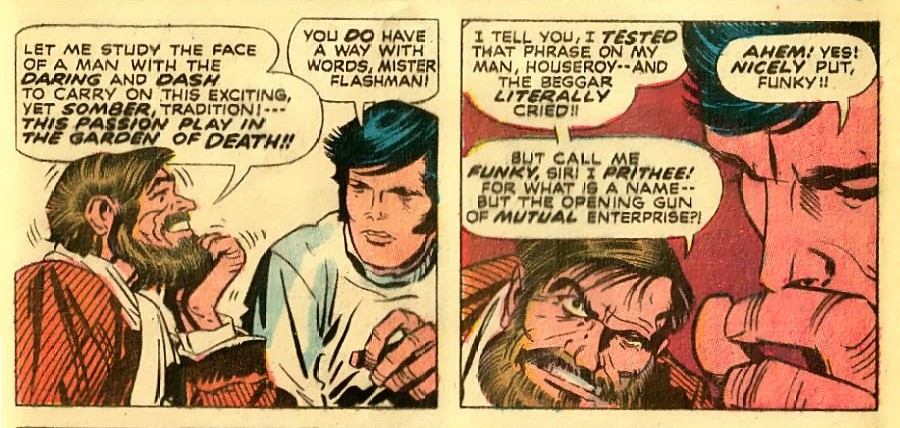

Funky Flashman

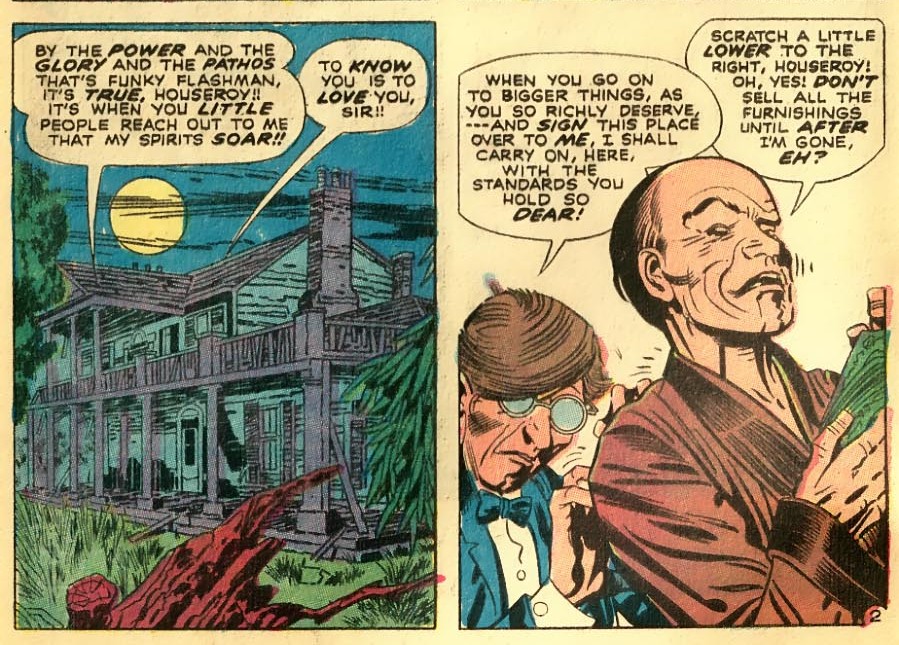

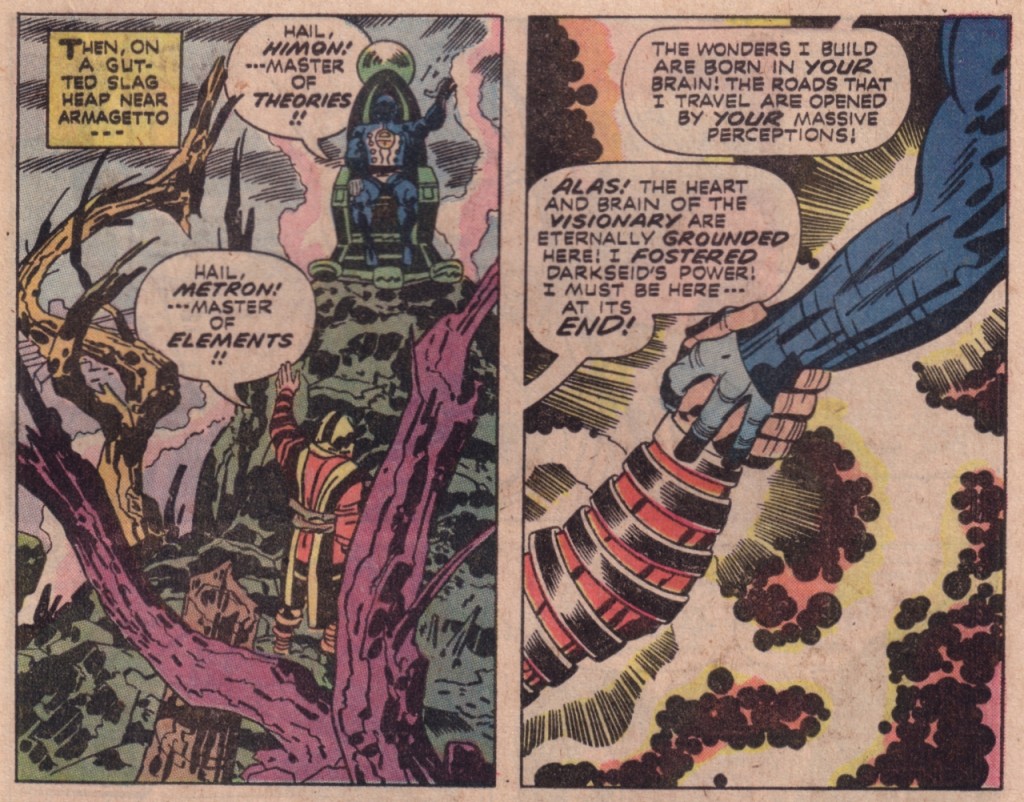

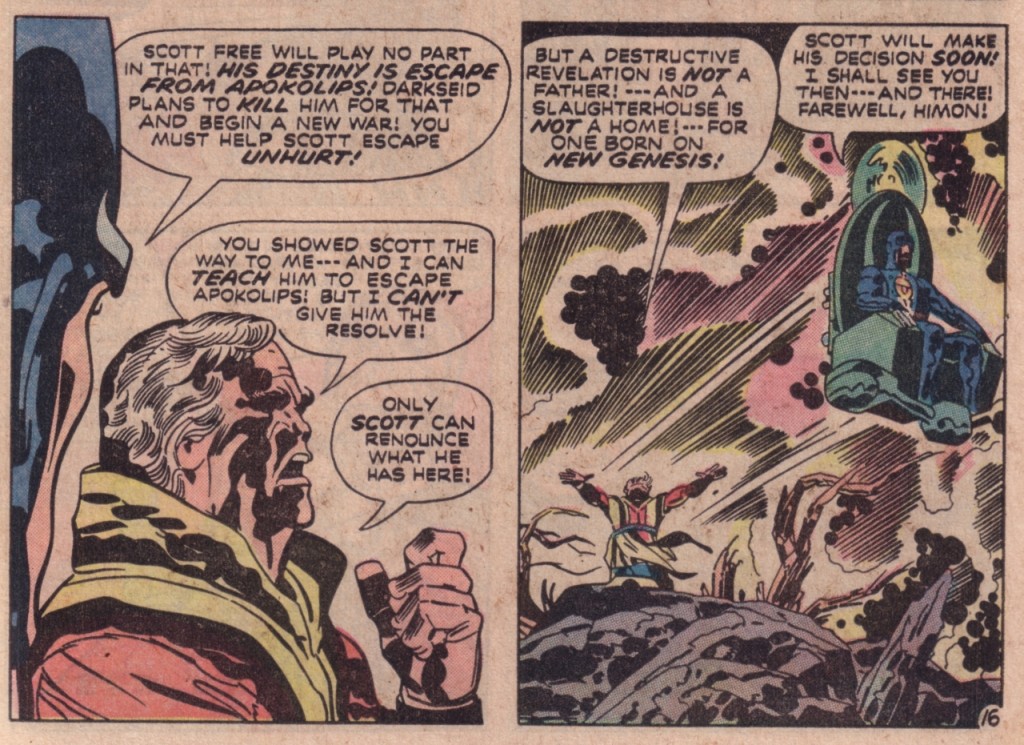

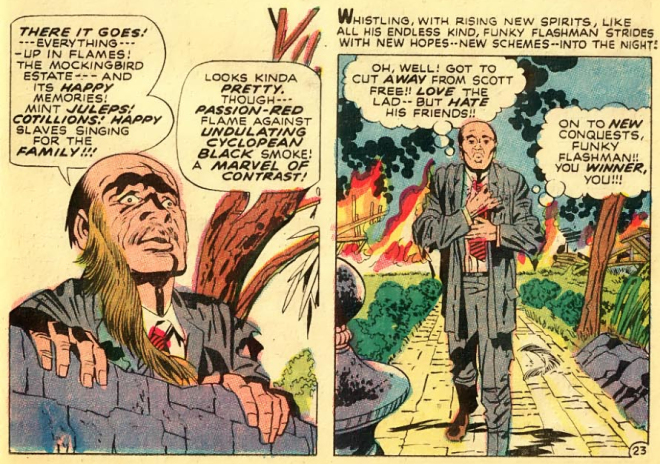

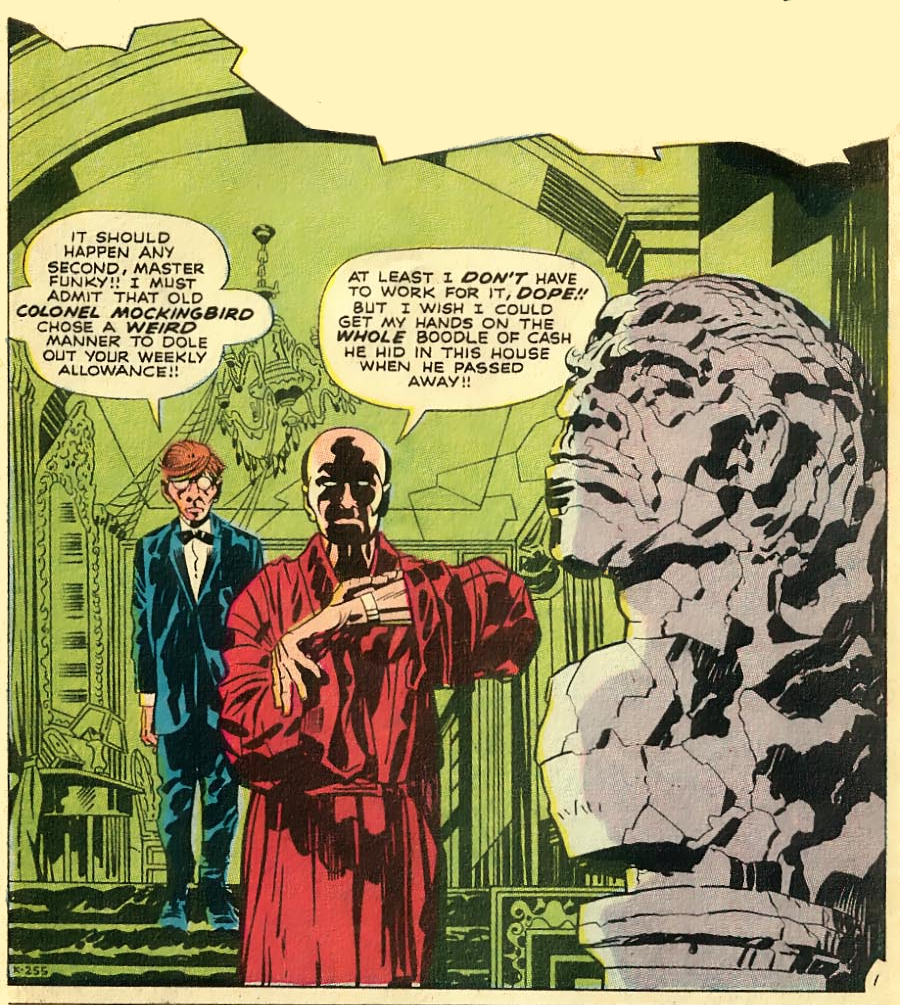

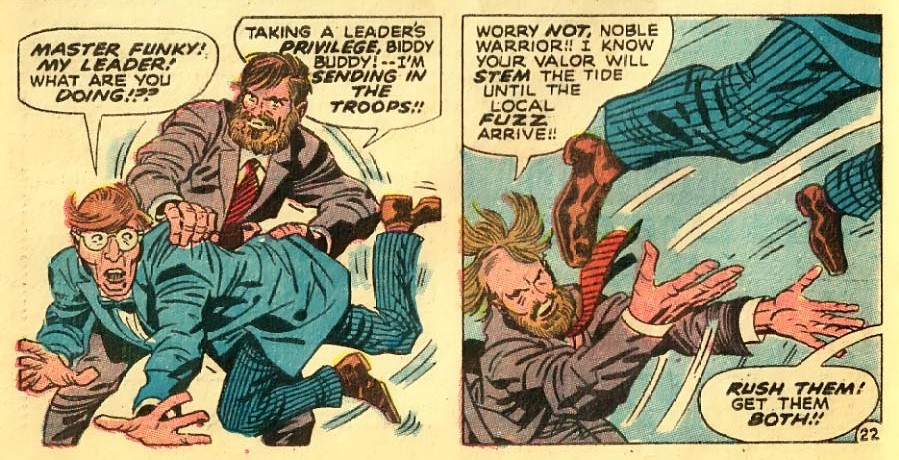

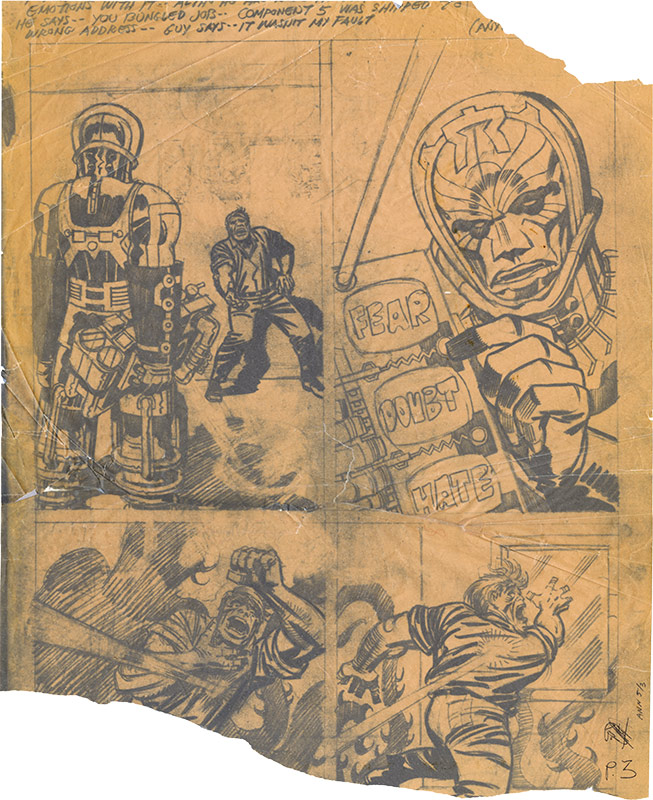

In Mister Miracle #6, Kirby unleashed a brilliant send-up of Stan Lee called “Funky Flashman.” Lou Mougin called it “one of Kirby’s best satires.” 20 (Mougin knew Kirby was no stranger to satire — 1967’s “This is a Plot?” in Fantastic Four Special #5 was filled with Kirby visual gags, including a book on Lee’s desk entitled Shakespeare Made Simple, perfectly encapsulating Lee’s Thor dialogue.) “Funky Flashman” is a tour de force, showcasing Kirby’s literary abilities as well as his exquisite eye for caricature, and proof that no one was ever better positioned or equipped to give Lee the treatment.

Stephen Bissette: 21

Kirby’s and Ditko’s work after departing Marvel was inherently reactionary, at first. Both writer/artists explicitly autopsied and rejected many of the core principles of the work they’d done at Marvel, countering the compromised heroes of the Marvel Silver Age, and even personifying and vilifying Lee himself via gross caricature (see Kirby’s Funky Flashman character in Mister Miracle). Ditko’s and Kirby’s conscious rejection, even vilification, of key characteristics of their collaborative work with Lee arguably and necessarily eschewed any emulation of Lee’s writing strengths and style.

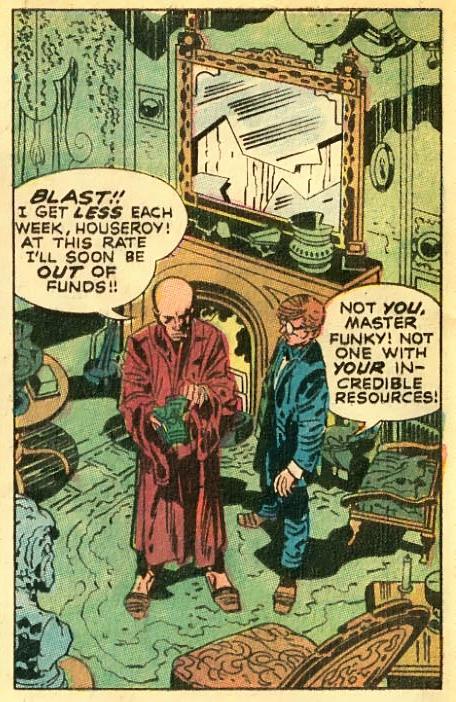

In the opening sequence, Funky is taking “bread” out of the mouth of a bust that resembles Kirby. This could be a reference to an event like an increase in Kirby’s page rate—on one such occasion it enabled him to stop doing layouts and cut back on his penciling page count, reducing Lee’s take for Kirby’s writing to just over half what it was.

In the opening sequence, Funky is taking “bread” out of the mouth of a bust that resembles Kirby. This could be a reference to an event like an increase in Kirby’s page rate—on one such occasion it enabled him to stop doing layouts and cut back on his penciling page count, reducing Lee’s take for Kirby’s writing to just over half what it was.

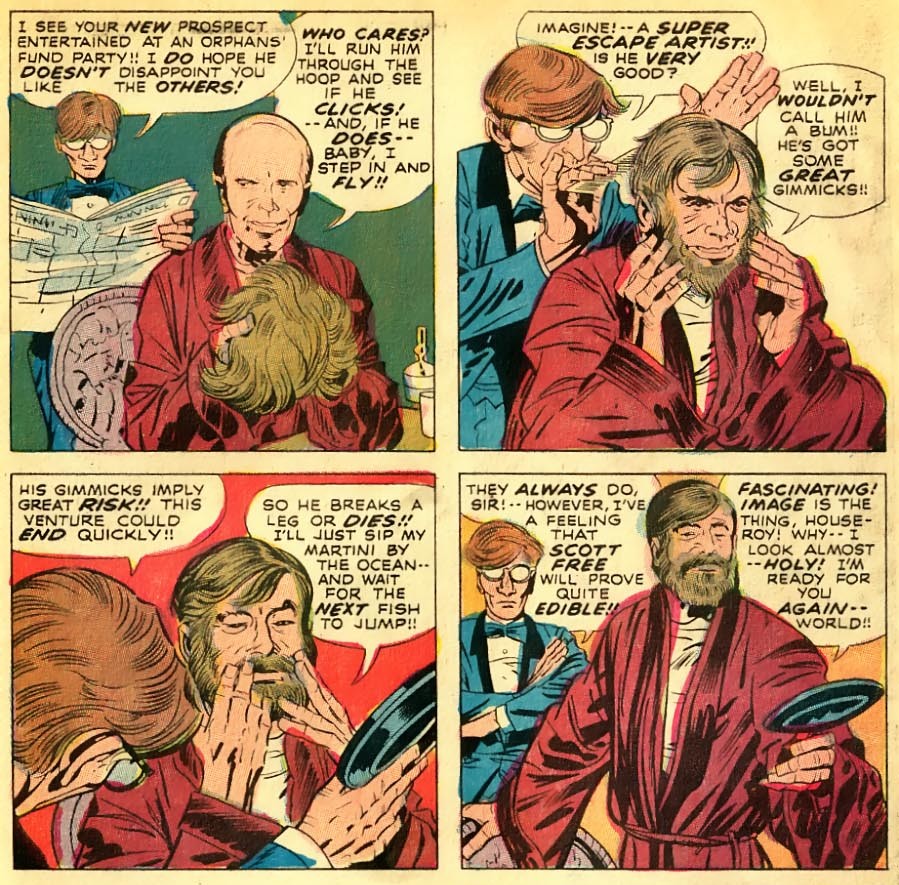

Kirby examines Funky’s attitude toward the talent.

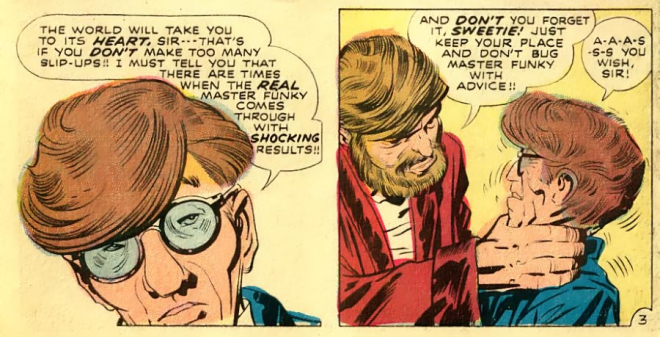

Roy Thomas once remarked, “Stan is always ‘on’…” 22

Like Funky, the real Stan Lee occasionally comes through with shocking results.

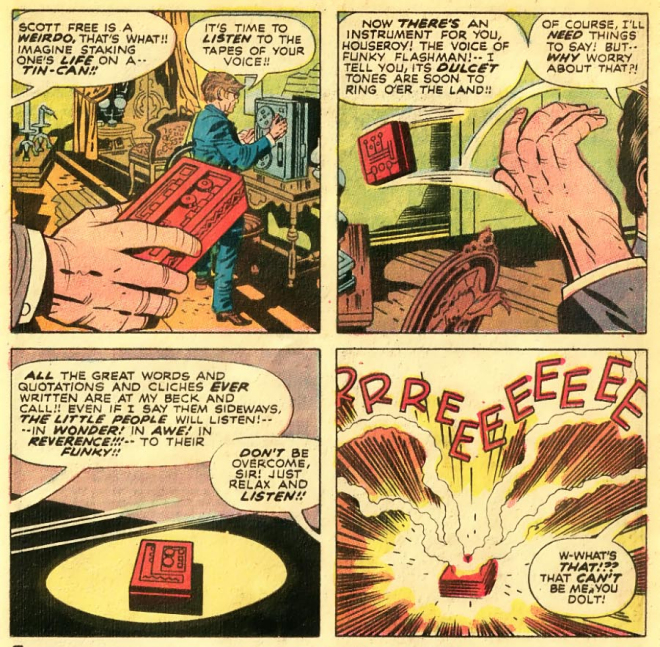

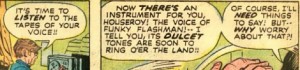

Funky loves the sound of his own voice. Kirby mentioned Lee’s recording device in the Pitts interview. 23

Funky turns out to be a bit of a sexist. In addition to being credited with promoting comic books to teach literacy to young children, Lee gutted Kirby’s strong female characters to allow them to demonstrate traditional gender roles to an impressionable audience.

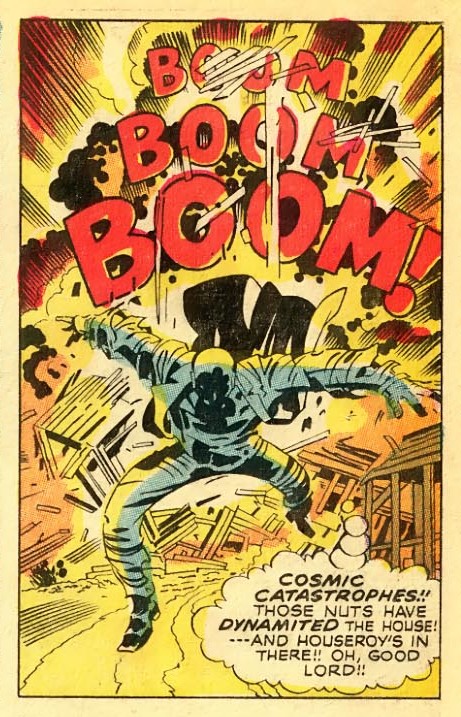

After causing the estate to go up in flames, Funky heads for Hollywood. Kirby injects another comment regarding the treatment of the talent at the family-run operation.

ROY: 24 I said to Jack, “I don’t take the Houseroy stuff that personally, because you don’t know me. My relationship to Stan was somewhat like what you said, and partly it’s just a caricature because I was there. And the name ‘Houseroy’ is clever as hell, and I kinda like it.” I’m even a sympathetic character because I got tossed to the wolves. (laughter)

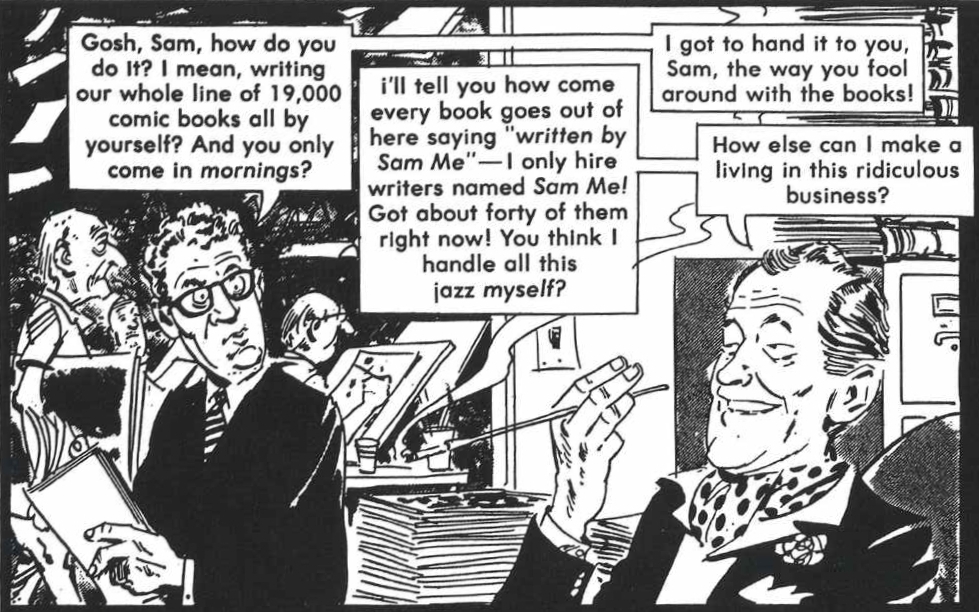

Funky had forerunners in the 1960s. Joe Simon depicted him as Sam Me in a 1966 issue of Sick Magazine 25, and Stan Bragg appeared in Angel and the Ape #2 (1968). 26

In both cases, the character took delight in signing his name to other people’s work. Physically, Stan Bragg and his sidekick are the Funky and Houseroy characters reversed, perhaps to add a layer of deniability. Plotting and scripting are credited to Sergio Aragones and Bob Oksner, but it’s not hard to imagine editor Joe Orlando’s input based on his own experience with Lee.

What Makes Stanley Run?

1986 [Pitts] 27

PITTS: Why did you leave the F.F. and Marvel that first time?

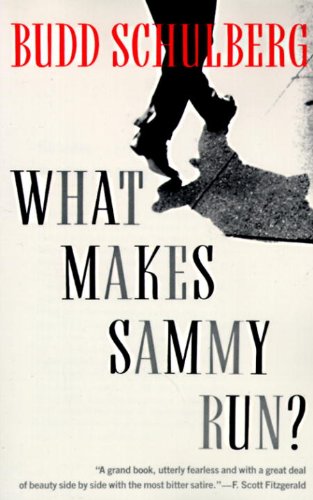

KIRBY: Because I could see things changing and I could see that Stan Lee was going in directions that I couldn’t. I came in one night and there was Stan Lee talking into a recording machine, sitting in the dark there. It was strange to me and I felt that we were going in different directions… I realized I was creating something I didn’t want to create. Did you ever read What Makes Sammy Run by Budd Schulberg?

PITTS: No.

KIRBY: Read What Makes Sammy Run. Sammy, in that book, is the kind of a character you wouldn’t want to be responsible for developing. I felt that I was developing a Sammy– which I was, in Stan Lee. I felt it was my time to go.

PITTS: You’re very cryptic, Mr. Kirby.

What Makes Sammy Run? 28

Sammy was waiting for them when they got home. With a face full of bad news. “Tough luck, kid,” he said. “I’m afraid your scenes didn’t go over like I thought they would.”

When the script was finished and Sammy was waiting for his next assignment, Julian didn’t like to sit around without writing so he started working on an original called Country Doctor because he thought it would help Sammy plead his case at the studio.

Julian wrote easily, and it was his sort of stuff, simple and human, and he had it finished in a week. For the next three days he wondered whether it was good enough to show Sammy. He had decided it wasn’t when Sammy came to him and said, “Say, I read that yarn of yours Blanche showed me. It’s pretty fair–got a couple of nice moments. I’ll see what I can do with it.”

“Well,” Julian said, “weeks went by and it looked like he’d forgotten all about my story, so I started helping him with his next screenplay because there didn’t seem to be anything better to do. And then one day Blanche happened to be reading through the trade paper and found this:

He handed me a ragged little clipping. I was beginning to feel like a district attorney. “Exhibit B,” I said.

Sammy was running through the room again as I started to read: “Sammy Glick makes it two in a row as his latest original, Country Doctor…” and handed the squib back.

“I guess you must have thought I was a little shell-shocked when you saw me after the preview last night. Well, maybe I was. Because that picture was the biggest shock in my life, Mr. Manheim. How do you think you’d feel going in to a movie cold and suddenly starting to realize you’re hearing all your own scenes?”

“The whole picture,” Julian was saying. “All those scenes I thought I was just doing for practice–actually showing on the screen–all mine–every line, mine–you know what I felt like doing, Mr. Manheim? I felt like jumping up right in the middle and screaming. I wanted to tell everybody there that the only line Glick wrote on Girl Steals Boy was the byline on the cover…”

There was no bitterness or anger in Julian’s story. It was full of mild wonder and deep resignation.

Wallace Wood paid tribute to What Makes Sammy Run?, likening Lee to Sammy Glick with his title “What makes Stanley run?” 29 Michael T. Gilbert described it like this: 30

Eventually [Kirby, Ditko and Wood] realized they were effectively co-writing the comics, but without extra credit or extra pay. Wood addressed this very topic in a bitter 1977 article for his Woodwork Gazette newsletter. He described an editor “Stanley” who “came up with two surefire ideas… the first one was ‘Why not let the artists WRITE the stories as well as draw them?’… And the second was… ALWAYS SIGN YOUR NAME ON TOP… BIG.”

The recording machine Kirby mentioned makes an appearance in “Funky Flashman.” Did he accurately capture Lee’s words from that night when he wrote, “Naturally, as your leader, my faithful pets, I can only say… and get this gem…”? Or did he overhear something more sinister? Based on the context of the Sammy reference, Lee might have been reading Kirby plots and ideas into the device.

The “notorious” TCJ interview

Patrick Ford on the interview: 31

The interview is a conversation. In conversation there is almost always use of hyperbole, comments which are exaggerated for humor (even if it’s an insulting humor), and comments which might be understood by the participants but might not be understood by the reader. Far from being angry Kirby was about as even tempered and sweet as any person in the history of the form. In no way does he have a reputation for being bitter or angry. There are numerous video clips of the man anyone can look at and he comes across as soft spoken, controlled, whimsical, anything but angry.

Gary Groth on the interview: 32

Jack’s comments about Stan revealed a lot about Jack’s recollection. I don’t know if his recollections were literally accurate; I guess nobody knows but Jack and Stan, but it certainly reflects how Jack perceived that, and I thought that was important. There’s a section where Jack said Stan didn’t write anything. I don’t think that’s literally true; I think from Jack’s point of view that’s true, because Jack felt he wrote the comic by pacing it, and drawing it, and writing the descriptions in the margins; he considered that writing. And you have to accept that as Jack’s perception, and you have to read between the lines. I think that also reflected a lot of bitterness on Jack’s part, and that revealed the extent of his resentment. He felt betrayed. I also think there was Stan’s public attitude that Jack took offense at, in the sense that Stan took too much credit. There was a feeling that Jack felt betrayed because Stan didn’t stand up for him; that Jack gave all the creative energy he could to Marvel, and he got f*cked as a result.

Neal Kirby on the interview: 33

Though my opinion may be viewed by some as non-objective, I can say that my father spoke the truth in this interview.

When Charles Hatfield declared as his proof, “Lee explicitly denied all this years later,” he went further: 34

In any case [Kirby’s] account seems self-mythologizing and is hard to credit. At one point Kirby refers to Lee as being “just still out of his adolescence,” which is inaccurate, and characterizes him as helpless and childlike, which is unlikely.

Hatfield’s reading of Kirby’s comment is pedantic. Kirby had known Lee since Stan was an adolescent, and was making a comment about his character rather than a statement of fact. A better choice of words would have been, “It’s like he never grew up.” The Kurtzmans had some observations to that effect. Paul Wardle: 35

Harvey Kurtzman claimed that Lee would return his original art to him (strips such as Hey! Look! that Timely published in the 1940s) only after drawing a big “X” through them with a black grease pencil. He also said Lee would sit on top of a filing cabinet and force the employees to bow to him on their way to work. Stan was reportedly an “enfant terrible” in those days, having been promoted when still a teenager by publisher Martin Goodman after the departure of Simon and Kirby.

Adele Kurtzman: 36

He would blow a whistle and everyone would have to start drawing. Frank Giacoia was busy reading The Daily News when this happened, so Stan sent him home. I guess artists were notorious goof-offs.

Hatfield’s charge of self-mythologizing shows Lee’s “history” is so pervasive it’s mistaken for the truth. After he’s spent decades repeating his version of events, Lee’s account is widely taken as fact. (It’s been disputed by Kirby, Ditko, Wood and other creators, but that only served to get them labeled: Liar, Unreliable, Eccentric, Drunk, Bitter, Demented, Senile. The moment one of them is quoted disagreeing with Lee’s claims, the label is the automatic response.) Hatfield has got the players reversed… it would have been closer to the mark if he’d called Lee the self-mythologizer, and stated Kirby used the interview to explicitly deny all of Lee’s claims. Lee’s denial should be taken as an outright endorsement of everything Kirby said.

In a fresh introduction to the interview when it was reprinted in the first volume of The TCJ Library, Groth added the caution, “Some of Kirby’s more extreme statements (e.g., ‘I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything’) should be read with a grain of salt…” 37 The line has been used to discredit any or all of Kirby’s “claims” in the interview. On the occasion of its posting on the TCJ website, for instance, a commenter recalled Groth as saying “some of Jack’s claims… weren’t exactly true.” Dan Nadel replied, 38 “That’s not accurate. Gary Groth published a note saying that some of the claims were possibly exaggerated (Groth never said they were not true), a thought I echoed upon publishing this on Monday.”

Groth later added, “when I said that Kirby’s claims were excessive, I did not mean to say that Kirby’s claim to have ‘written’ his Marvel work was not without merit, only that, as I recall, such claims as his that Lee never wrote a thing in his life were, well, obviously excessive.” 39 Even during the interview Groth made it clear his disclaimer would be unlikely to support the broader interpretation.

1989 [Groth] 40

GROTH: At the risk of sounding partisan, let me ask you this: every time I read something by Stan or see Stan speak publicly, I’m struck by how obvious a bullshit artist he is. Was he always that way?

ROZ KIRBY: Yeah.

The only comments on Kirby’s part that call for scrutiny are the ones to which Groth refers, above. “I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything… If Stan Lee ever got a thing dialogued, he would get it from someone working in the office. I would write out the whole story on the back of every page. I would write the dialogue on the back or a description of what was going on. Then Stan Lee would hand them to some guy and he would write in the dialogue.” 41

If the words “for all I know” are taken as implied, everything Kirby said becomes true. Prior to his 1970 departure, Kirby would have been aware that “some guy in the office,” namely Roy Thomas, was doing precisely that on books which Lee had grown tired of dialoguing, or had lost the plotting credit but was still being credited for editing. Thomas states 42 that Lee’s editing on his books was of the hands-off, sight unseen variety.

Fantastic Four #6 is an interesting study: in a Kirby Collector article, 43 Mike Breen shows that Kirby dialogued it himself, and suggests Lee was an absentee editor that month. Dick Ayers, the inker on the issue, once described his reaction to learning his “Kirby/Ayers” signature was being whited out in production. 44 In this case it was replaced with Lee’s “Stan Lee + J. Kirby” at the beginning of all five chapters, despite the lack of evidence that Lee even laid eyes on the book. There is, however, no question who received the writer’s pay and the editor’s salary for FF #6.

There is photographic evidence that Lee spent time with some of the pages; some even bear notes and comments in his handwriting. To state, however, with no eyewitness corroboration, that he wrote the copy himself, would be to fall into the same trap that was decried at the beginning of part one of this article. Let’s hedge our bets against some Marvel office worker coming forward in the future to lay claim to the task. To use Lee’s qualifying words to Jonathan Ross regarding Ditko’s creatorship, 45 “I consider” Stan Lee to be the one who added the dialogue and captions.

Filling in the balloons, connecting the dots

Like Piscine Molitor Patel in Life of Pi, Stan Lee is the myth-making, untrustworthy narrator in The Marvel Story. In opposition to Lee’s version of events, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko have provided interviews and writings that form a historical record of immeasurable value based on their first-hand accounts. These are consistent internally and with each other’s, and with those of other of Marvel’s designated pariahs from the 1960s.

Everyone from fans to scholars claims Lee’s genius was the ability to surround himself with artistic talent. In reality, it was the ability to recruit writer-artists who were desperate enough to put up with, not just Marvel’s poor page rates, but also having their pay appropriated for the writing they did. Lee had a tremendous effect on the product Marvel ultimately published, not all of it positive, but his creative work began on Kirby’s books when Kirby first relinquished the pages to him. Lee then made his mark by adding his unique dialogue and by demanding redraws to reconfigure stories in a way that made sense to him.

Stan Lee encourages the belief that the proliferation of margin notes on Kirby’s pages marked the point where Kirby came into his own, plotting-wise, but Stan Taylor proved beyond a reasonable doubt that Kirby plotted the earliest issues of the superhero revival. Other evidence confirms Kirby’s contention that he always did his own plotting.

In his deposition creation accounts, Lee’s stated motivation in every case was the desire to create something different. Astonishingly, none of the creations actually were different. Jack Kirby never said he was trying to do something different, he often simply did a thing that was the same as something he’d already done. The idea that Lee’s “different” creations somehow coincidentally always turned out the same as older Kirby concepts is somewhat improbable.

Kirby portrayed the story conference as the place where he would tell Lee what was happening in the story. Looking at what came out of it, he was being modest. The story conference was where Jack Kirby spun plots for all the stories, even those he wouldn’t draw. Not only did he plot the stories, he created the characters, and he brought superheroes back to Marvel to enable Goodman’s comics division to return from the brink of oblivion. His closed-door meetings with Lee were where he pulled back the curtain on his work to reveal the Marvel Universe to an audience of one.

When Stan Lee wrote the captions and the dialogue based on Kirby’s margin notes, sometimes he used Kirby’s words. At the very least, the Kirby Version should be given the same consideration as the Lee Version, and when we tell the Jack Kirby story, we can’t go wrong using Kirby’s words.

Articles in this series:

* Interviews

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part one

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part two

* The Marvel Method According To Jack Kirby – part three (you are here!)

Footnotes

Repetition of citations allows linking back to individual quotes.

back 1 Tom Crippen, “Stan,” The Hooded Utilitarian, 30 September 2008 (originally ran in The Comics Journal, February 2008).

back 2 Neal Kirby deposition, 30 June 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit G.

back 3 Steve Ditko, “A Mini-History 13: Speculation,” The Comics, v14n8, August 2003.

back 4 Stan Taylor, “Spider-Man: The Case for Kirby,” 2003. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 5 Daniel Keyes interviewed by Will Murray, Alter Ego #13, March 2002.

back 6 Richard Kyle, letter to the editor, The Jack Kirby Collector #13, December 1996.

back 7 Jack Kirby interviewed by Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 8 Stan Lee, Origins of Marvel Comics, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1974.

back 9 Stan Lee deposition, 13 May 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit I, and 8 December 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit J.

back 10 Stan Lee deposition, 13 May 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit I, and 8 December 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit J.

back 11 Tj Dietsch, “C2E2 2015: S.H.I.E.L.D.,” Comics News blog, Marvel.com, 26 April 2015.

back 12 Joe Sinnott declaration, 25 March 2011, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 92.

back 13 Jim Woodring, “Jack Kirby: Reminiscences, Tributes and Critical Commentary,” The Comics Journal #167, May 1994.

back 14 Jim Steranko, “The Man Who Was The King,” Hogan’s Alley #1, Fall 1994. Reprinted in The Jack Kirby Collector #8, January 1996.

back 15 Neal Kirby deposition, 30 June 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 102, Exhibit G.

back 16 Stan Goldberg interviewed by Jim Amash, Alter Ego v3 #18, October 2002.

back 17 Ken Viola, “Jack Kirby – The Master of Comic Book Art,” introduction to his interview of Kirby for the film, The Masters of Comic Book Art. Published in The Jack Kirby Collector #7, October 1995.

back 18 Stan Taylor, “Spider-Man: The Case for Kirby,” 2003. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 19 Michael Vassallo, by email, 22 October 2014 and 4 January 2015.

back 20 Lou Mougin, “New Gods for Old: A Hero History of Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Part II,” Amazing Heroes #21, March 1983.

back 21 Stephen Bissette, “Marvel/Disney v Kirby: Part 2,” SRBissette.com, March 2nd, 2012.

back 22 Roy Thomas interviewed by Jim Amash, conducted by phone in September 1997, published The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 23 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 24 Roy Thomas interviewed by Jim Amash, conducted by phone in September 1997, published The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 25 “The New Age of Comics,” written by Joe Simon, art by Angelo Torres, Sick Magazine, November 1966.

back 26 “Most Fantastic Robbery in History,” plotted by Sergio Aragones, co-written and penciled by Bob Oksner and inked by Wally Wood, Angel and the Ape #2, November 1968.

back 27 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 28 Budd Schulberg, What Makes Sammy Run? Vintage Books, © 1941, 1968, 1990.

back 29 Wallace Wood, “What makes Stanley run?” Woodwork Gazette v1n5, 1980.

back 30 Michael T. Gilbert, “Total Control: A Brief Biography of Wally Wood,” Alter Ego 3 #8, Spring 2001.

back 31 Comments section, “TCJ Archive: Jack Kirby Interview,” The Comics Journal website, 26 May 2011.

back 32 Gary Groth interviewed by Jon B. Cooke, conducted February 1998. The Jack Kirby Collector #19, April 1998.

back 33 Comments section, “TCJ Archive: Jack Kirby Interview,” The Comics Journal website, 2 June 2011.

back 34 Charles Hatfield, Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby. University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

back 35 Paul Wardle, “The Two Faces of Stan Lee,” The Comics Journal #181, October 1995.

back 36 Adele Kurtzman to Blake Bell, I Have to Live with This Guy!, TwoMorrows, 2002.

back 37 Milo George, Editor. The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby. Fantagraphics Books. Seattle. May, 2002.

back 38 Comments section, “TCJ Archive: Jack Kirby Interview,” The Comics Journal website, 25 May 2011.

back 39 Gary Groth, personal email, 1 January 2015.

back 40 Jack Kirby interviewed by Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 41 Jack Kirby interviewed by Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 42 GUSTAVESON: Is Stan Lee a “fan”? THOMAS: Lord, I don’t think so! I mean, he probably was when he got into the field as a teenager, but I don’t really think that Stan has enjoyed being in comics… One of the reasons Stan liked my writing, for instance, was that after a few issues he felt he could trust me enough that he virtually never again read anything I wrote—well, at least not more than a page or two in a row, just to keep me honest. Roy Thomas, interviewed by Rob Gustaveson, The Comics Journal #61, Winter 1981.

back 43 Mike Breen, “That is strong talk… whoever you are,” The Jack Kirby Collector #61, Summer 2013.

back 44 “So… regarding those Kirby / Ayers signatures… I always put the signatures on our work together just as I always sign my work. I noticed that the ‘whiteouts’ were happening and it sure didn’t make me happy for I usually had the signature as part of the composition of the drawing. It was a sore point. I’m not keen on the credit boxes that are added to the drawing and confuse the composition of my drawing.” Dick Ayers, Kirby-L, the Jack Kirby Internet mailing list, 8 December 1998.

back 45 Jonathan Ross, “In Search of Steve Ditko” (television documentary), BBC Four, 16 September 2007.