Thanks to ICS’ Peter Coogan, Craig Fischer sat on The Auteur Theory of Comics panel in San Diego last month. Craig is an Associate Professor of Film and Cultural Studies at Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina, USA. – Rand Hoppe

I’m late to appreciate Kamandi. In the 1970s, when I was a kid buying comics on spinner racks in drug stores and supermarkets, I sampled a couple of issues and wasn’t impressed. I was a Planet of the Apes fan, and I felt (not without reason) that Kamandi ripped off Apes’ premise; also, the issues I read, inked by D. Bruce Berry, looked less electric and kinetic than the Kirby art in Marvel’s Greatest Comics. So I let Kamandi drift onto my list of unread funnybooks.

This summer, however, at Heroes Con in Charlotte, I bought a bargain-basement copy of the first volume of DC’s Kamandi Archives, which reprints the first ten issues. This time, I like Kamandi much better, particularly “Flower!”, originally presented in Kamandi 6 (June 1973), a story which strikes me as both touching and innovative. To explain why “Flower!” is so exceptional, I need to define a concept from literary and film studies–focalization–and apply the concept to Kirby’s narrative techniques in “Flower!”

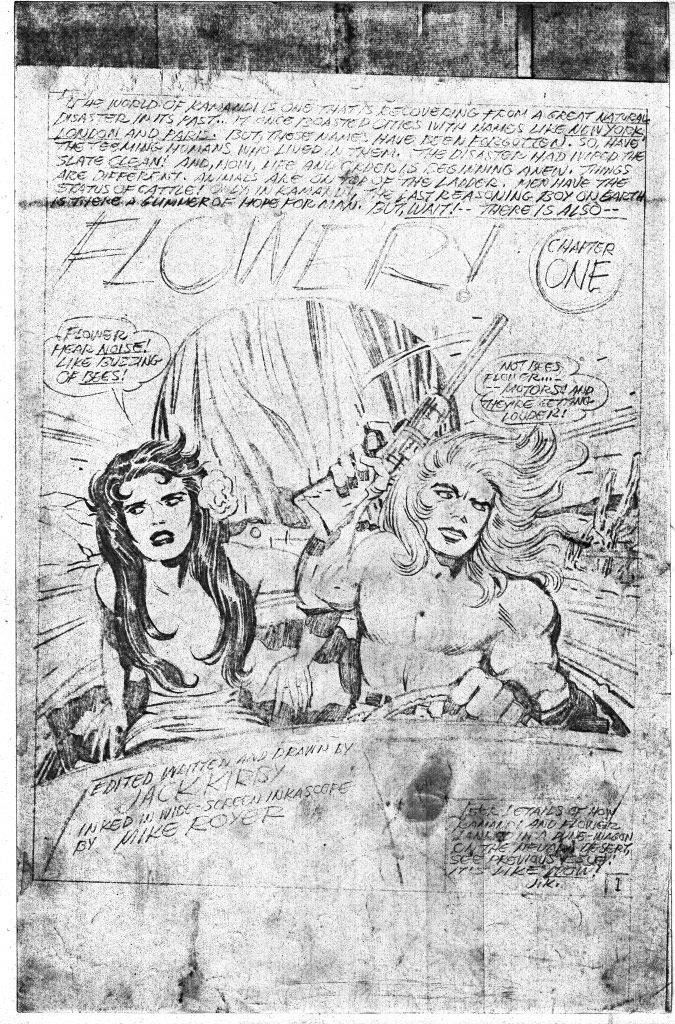

Adjusted scan of a photocopy of Kirby’s pencil work for the first page of “Flower!” – from the Kirby Museum’s Pencil Art Photocopy Digital Archive, with thanks to the Kirby family.

Focalization is the term used by narratologists—those scholars who study how stories work—to identify how stories are often filtered through a character who chooses what facts and details to emphasize and omit. As Manfred Jahn defines the term:

Focalization is the submission of (potentially limitless) narrative information to a perspectival filter. Contrary to the standard courtroom injunction to tell “the whole truth,” no-one can in fact tell all. Practical reasons require speakers and writers to restrict information to the “right amount”—not too little, not too much, and if possible only what’s relevant. (The Cambridge Companion to Narrative, 94)

Of course, “relevant” is an ambiguous term here. Relevant narrative information can refer to scenes that advance a character towards a goal, or to details that enrich a feeling that an author wants to convey to his/her audience. Focalization reminds us that storytelling is by definition incomplete, slanted, subjective: the Beowulf poet sings the praises of the Grendel-killer, but when John Gardner focalizes the same story through Grendel’s own perspective, the changes are profound.

When discussing visual media like comics and film, we should not equate focalization with the first-person point of view, with actual vision through a character’s eyes. In the film The Son (Le fils, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, 2003), our anchor of focalization is Olivier (Olivier Gourmet), a carpentry teacher at a reform school who mentors Francis (Morgan Marinne), a delinquent who (it is gradually revealed) murdered Olivier’s infant son. The Dardennes avoid Olivier’s literal point-of-view, opting instead for a prowling hand-held camera that struggles to keep up with Olivier as he instructs his students and watches Francis carefully, uncertain if he should take revenge. Here’s a shot from The Son:

This shot is a third-person portrait of Olivier as he stares at Francis, but we still feel Olivier’s anger and confusion. On a basic level, Olivier is in virtually every shot of The Son, a continual presence that elicits our attention. Narratively, Olivier is the agent through which we gradually figure out the story; we find out about the dead child through Olivier’s actions and conversations. Focalization is about the flow of story information through the perceptions of a particular character, but that doesn’t mean that readers and spectators have to be imbedded in that character’s literal vision.

What surprises me about focalization is how easily and quickly our interest can slide from one character to another. Another example from the movies: the shower scene and its aftermath in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). During Mother Bates’ attack, we feel the terror of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), but after Marion’s death, our focus switches to Norman (Anthony Perkins), the milquetoast charged with cleaning up his mama’s mess. We watch as Norman slowly and carefully mops the floor, wraps Marion’s body in the shower curtain, and deposits the bundle in the trunk of Marion’s car. He then drives the car into a nearby swamp, and when the car briefly refuses to sink, I (and other spectators) have a strange reaction: I feel for Norman, I worry that he won’t be able to hide the murder evidence. Hitchcock successfully swings Psycho’s focalization from Marion to Norman, prompting our sympathy for (spoiler alert, 50 years after the fact!) a homicidal psychopath.

How does focalization work in comics—and, more specifically, in Kirby’s comics? How does Kirby use character presence and action to establish focalization, and does he shift among characters like Hitchcock does? In order to answer these questions, however tentatively, I’ll now look closely at “Flower!” If you have a copy of that story, get it and read along with me.

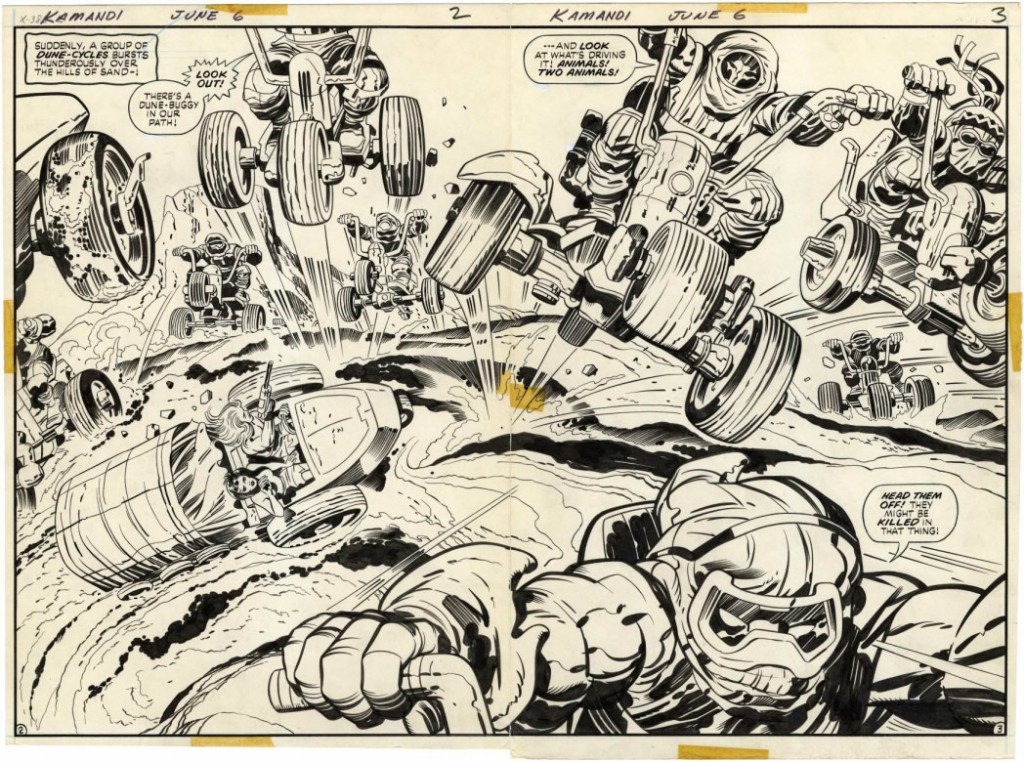

“Flower!” begins with a six-page “Chapter One.” The story opens with Kamandi and Flower driving a “dune-wagon” across a desert landscape, until (in a typically kinetic Kirby splash on pages two and three) a squad of masked figures on motorcycles erupts in their path. The ensuing collision and confusion of vehicles prompts Kamandi to fire a rifle and shoot out one of the cyclists’ tires, after which another of the masked riders throws a “toss-truncheon” at Kamandi, knocking him unconscious. The final page of Chapter One reveals that the motorcyclists are tigers, zookeepers charged with protecting animals from poachers while guarding a wildlife sanctuary.

In this first chapter, Kirby shows an effortless ability to shift our focus away from one group of characters to another. On the first page, Kamandi and Flower are clearly center stage, presented as they are in tableau-style medium close-up, and the tiger-cyclists have yet to appear in-panel (though both Kamandi and Flower hear the roar of their motors). On the next page, however, the riders suddenly explode into our attention. Kirby draws them bounding through the air, one rider in a particularly extreme close-up at the bottom of page three. In this composition, Kamandi and Flower are presented as more distant figures—we now see them from above, and we’re further away from them—as they swerve their vehicle to avoid hitting the cyclists.

A scan of the original art of Kirby’s and ink artist/letterer Mike Royer’s page 2 and 3 spread for “Flower!” – from the Kirby Museum’s Original Art Digital Archive, with thanks to Albert Moy.

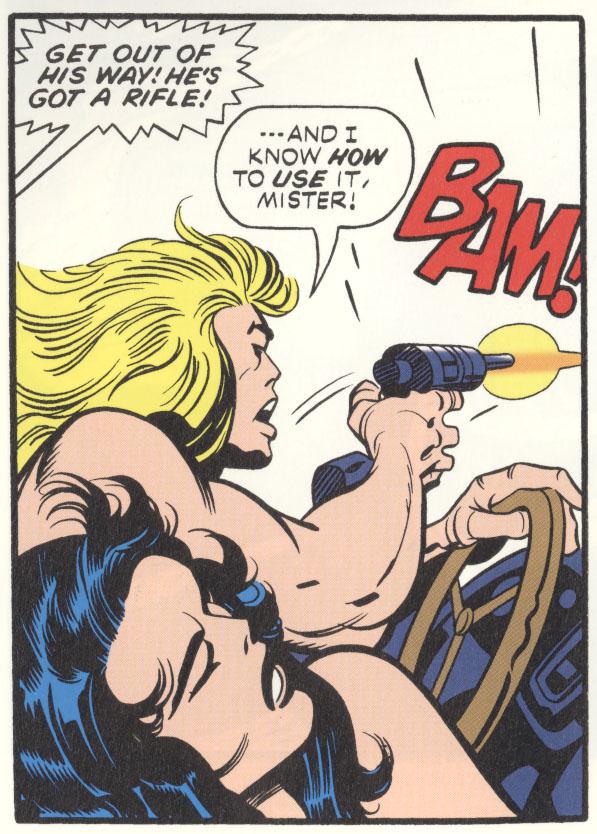

Throughout the rest of Chapter One, Kirby continues this process, minimizing his focalization on Kamandi and Flower while maximizing his (and our) attention on the cycle-tigers. Kirby does this partially through word balloons. As readers, we naturally gravitate to word balloons, and the tails of the balloons literally point us to the figures “speaking” in a specific panel. On page four of “Flower!”, there is a panel that returns us to a close-up on Kamandi and Flower, and Kamandi yells while firing his gun:

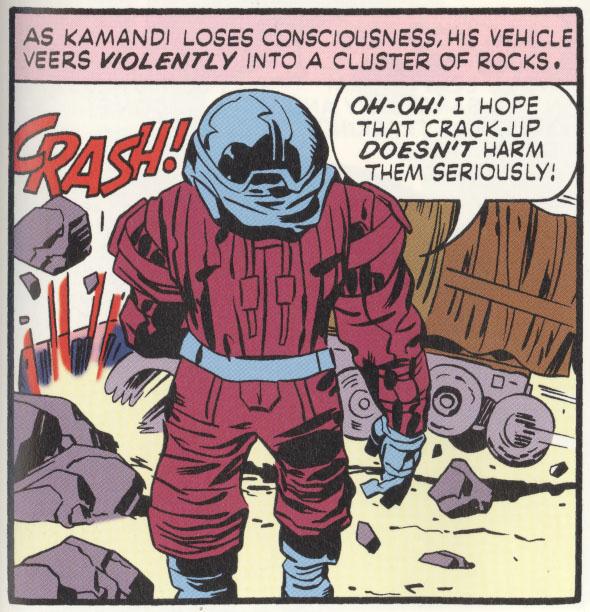

“Flower!” page 4 detail. Jack Kirby, story, pencil art, dialogue. Mike Royer, ink art & lettering. Jerry Serpe, color guide. Scan from Kamandi Archives, Volume 1, 2005.

This is the last time Kamandi speaks in Chapter One. The last three pages of the chapter are a tiger gab-fest, with the zookeepers talking about Kamandi’s cleverness as an “animal” and their plans to take Kamandi and Flower to the wildlife preserve. All these word balloons are arrows pointing us to the tigers both as characters and as visual presences on the page. By the end of page five, we’ve shifted our interest to the tigers so decisively that we’ve almost forgotten about Kamandi, even when his dune-wagon crashes into rocks.

Even though the caption describes the accident as “violent,” Kirby’s drawing treats it as an unimportant event—so unimportant that it is mostly obscured by the body of one of the cyclists, who is now in the literal and figurative center of our attention. Our interest on the tigers solidifies on the final page of the chapter, where the action slows down and the riders’ dialogue defines them as likeable and sympathetic. In the space of six pages, Kirby shifts his focalization from Kamandi—the protagonist we should be focusing on, after all, since it’s his comic book—to anonymous cyclists who blossom as characters when their true occupations and natures are revealed.

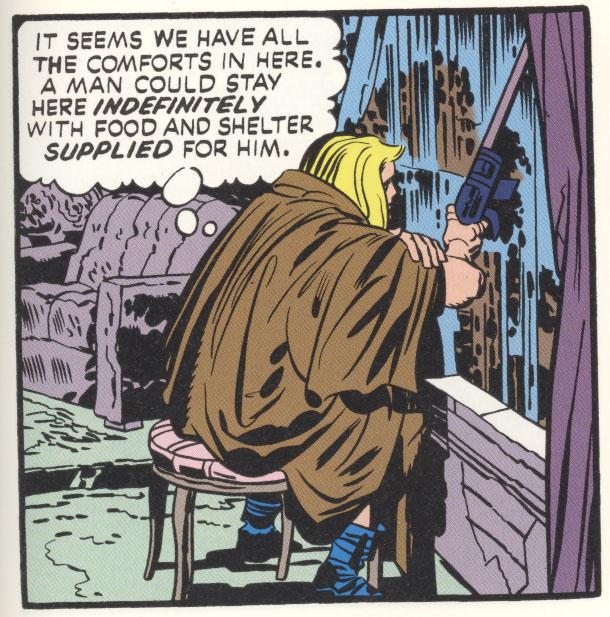

During the next fourteen pages, the focalization decisively returns to Kamandi and Flower. The tigers deposit Kamandi and Flower in the wildlife preserve and vanish. Kirby’s story alternates between scenes of relative peace (Kamandi and Flower gently wake up in their vehicle, and later inhabit a comfortable house) and eruptive violence, as when Kamandi fights to establish himself as the leader of the “animal” herd, and protects himself and Flower from the pumas’ initial kidnapping (or “poaching”) attempt. Kamandi’s mood in this middle section of the story is cautious optimism. Though he knows that he’s been deposited in a zoo, he also realizes that the zoo provides him with the most security he’s had since he hid in his grandfather’s bunker.

He’s begun to make plans for the future too. He’s thinking about staying in the house “indefinitely,” and earlier he seizes on Flower’s suggestion that he should teach the herd to speak and behave like human beings. (Kamandi’s dialogue on page 14, panel 2: “Man’s road back has to start somewhere! Why not here? I—I’ll give the teaching ‘thing’ a whirl!”) Kamandi is also overjoyed to have Flower in his life. When he meets her in the previous story, “The One-Armed Bandit!” (Kamandi 5, May 1973), Kamandi is astonished that she can talk, and their brief relationship is one full of affection and protection; note the encouraging way Flower strokes Kamandi’s forearm when he’s assuming the leadership of the herd (and mulling over the teaching idea) in the first panel on page 14 of “Flower!”. Before tragedy strikes, Kamandi has a home, a purpose, and potentially a mate.

At the end of “Flower!”, the pumas attack again, and Flower is killed before the tiger-rangers can arrive to arrest the poachers. As the tigers pour into Kamandi’s house, they also pour into the story’s panels, vying for our attention. Meanwhile, Kamandi says nothing as he carries Flower’s body over to the same sofa where, a few minutes before, Flower covered herself with a blanket and whispered “Flower feel warm and safe. Kamandi near—Kamandi brave.” We do, however, see Kamandi in close-up, wordlessly weeping over Flower’s dead body. During the last two pages, Kirby returns somewhat to the storytelling approach of Chapter One, as he chooses to again displace Kamandi as our central focus in favor of the tigers, a choice that gives “Flower!” elegant narrative bookends.

The effect of this second shift in focalization, however, is very different from the first. In Chapter One, we connect with the tigers when we realize that they intend to act kindly towards Kamandi and Flower. The end of “Flower!”, however, exposes a callous speciesism among the tigers, and creates an ironic contrast between Kamandi’s sorrow and the condescending tiger comments that end the story.

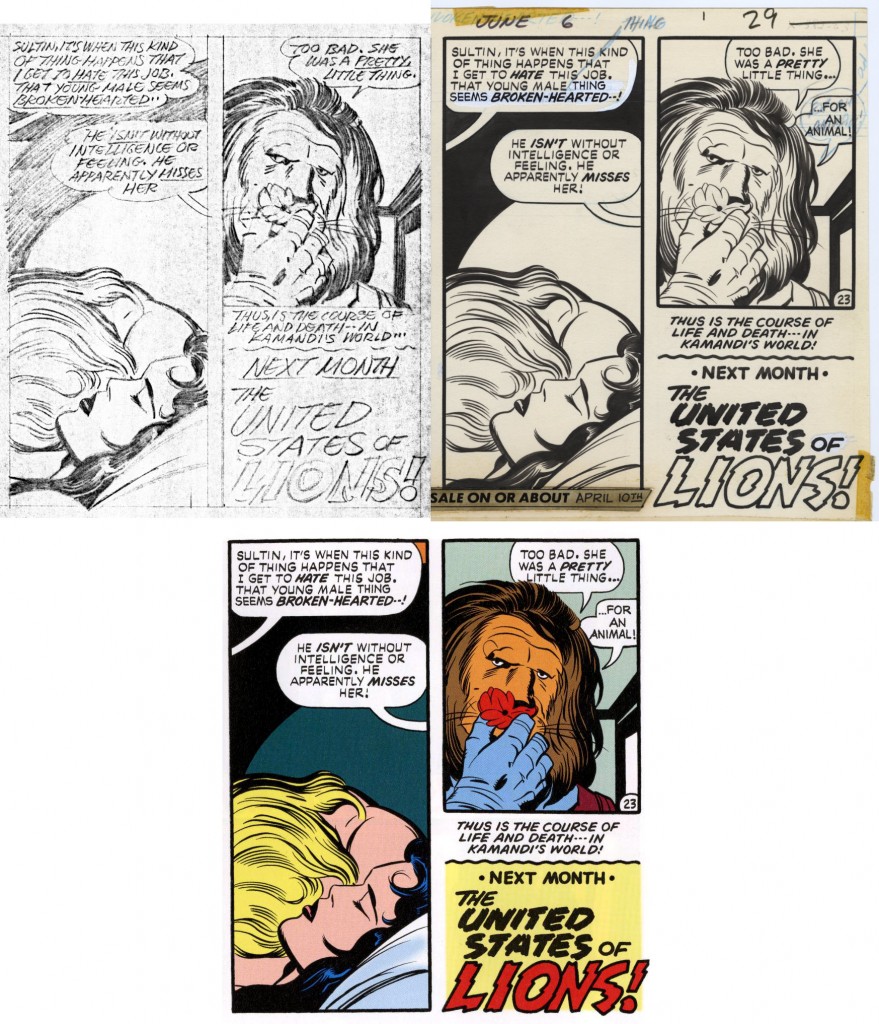

A photocopy of Kirby’s pencil work, Kirby’s and ink artist/letterer Mike Royer’s original art and DC’s Kamandi Archive 1 with color guides by Jerry Serpe.

Note that “thing” and “…for an animal!” were not on the photocopy of the pencil work, but were added as corrections to the lettering on the original art.

This conclusion is devastating. All the optimism of Kamandi’s stay at the zoo drains away. By now, I’ve read virtually all of Kirby’s Kamandis, and the conclusion of “Flower!” most forcefully conveys to me Kamandi’s plight as a disposable animal in the post-Great Disaster world. It’s Kirby’s ability to reintroduce a technique from earlier in the story (the focalization shift) and use it to reveal a new perspective on the characters and events (the tigers’ discrimination) that makes this moment so powerful.

I realize that my argument here is incomplete and a little slippery; for instance, I should’ve defined the difference between focalization and “identification,” and talked about why I mistrust the latter term. (In my home discipline of film studies, identification is freighted with other schools of thought—particularly psychoanalysis—that I consider seriously flawed.) I haven’t discussed the moments in the center section of “Flower!” where the reader is privy to information that Kamandi and Flower don’t know, such as the fact that they’re being secretly watched by both the pumas and tigers. And I should’ve examined more Kamandis to see if ironic focalization shifts as in “Flower!” are common in Kirby’s work. Still, writing this post has led me to value Kamandi more than ever.