Previous – 19. Spider-man: The Case For Kirby | Contents | Next – 21. Brand New World

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

BULLPEN? BULLSHIT!!

On March 16th 1965, an 82 year old German Jew, who had escaped the horror of Nazi Germany, had run out of alternatives. Alice Herz’s campaigns to end the war in Viet Nam had proven fruitless. In a final act of desperation Alice went outside and on an urban Detroit street doused herself with gasoline and set herself on fire, thus becoming the first American to self-immolate in protest of the war. She wasn’t the last. This human torch didn’t fly or throw flame balls- she died a horrible painful death. Herz wrote a last testament, which she distributed to several friends and fellow activists before her death. The testament specifically refers to her decision to follow the protest methods of the Buddhist Vietnamese monks and nuns, whose acts of self-immolation had received worldwide attention. Confiding to a friend before her death, Herz remarked that she had used all of the accepted protest methods available to activists—including marching, protesting, and writing countless articles and letters—and she wondered what else she could do. Later in March, Martin Luther King would lead a civil rights march on Selma, Alabama. In April, 25,000 people would march on Washington D.C. in protest of the war. The perfect storm of civil disobedience had arrived and America would never be the same.

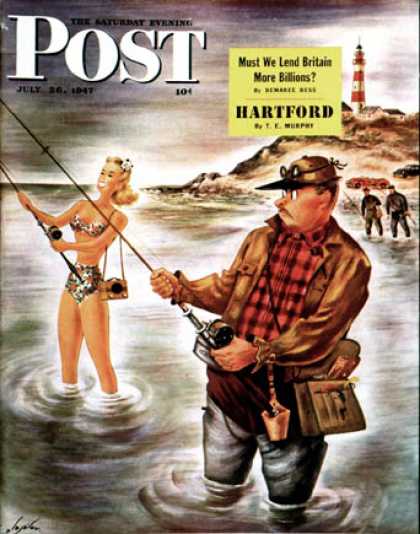

Working away – Hot day in Detroit

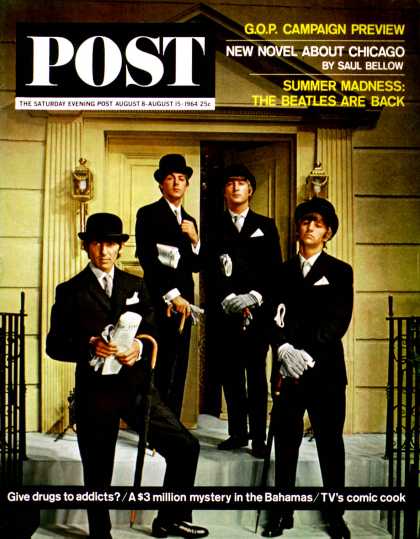

Meanwhile, back in England, the Beatles were awarded MBE’s (Member of the Order of British Empire) at Buckingham Palace; much to the dismay of the stodgy aristocracy. Prime Minister Harold Wilson explained, “I saw the Beatles, as having a transforming effect on the minds of youth, mostly for the good. It kept a lot of kids off the streets. They introduced many many young people to music, which in itself was a good thing. A lot of old stagers might have regarded it as idiosyncratic music, but the Mersey sound was a new important thing. That’s why they deserved such recognition.” – That, plus the millions of pounds that the Beatles and their imitators had brought to the British economy.

America was on fire! Los Angeles was ablaze, In perhaps the worst rioting in American history the black residents of the Watts section of L.A. said enough was enough. For 6 days in August 1965 they burned and rioted in defiance of a police force they felt had a long history of brutality and prejudice against the black populace. Seen as part of the civil rights movement that had been active and growing for decades, these riots were the resultant explosions of a long simmering animosity. After the Watts riot, inner cities boiling over became commonplace with it being a rarity for a major city to be spared.

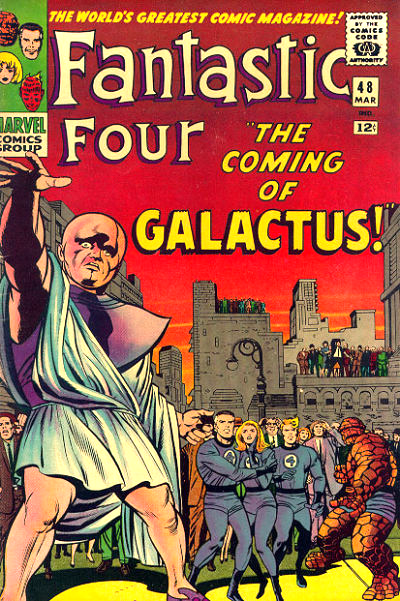

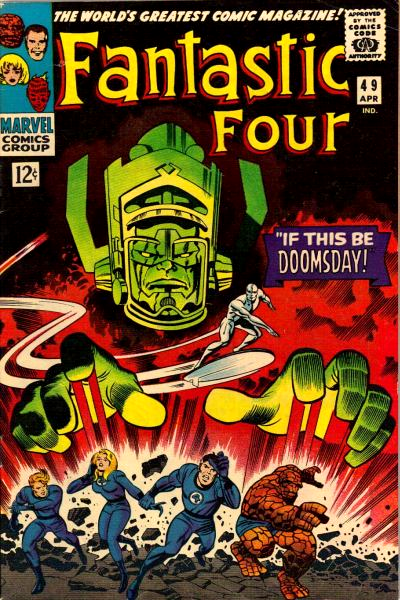

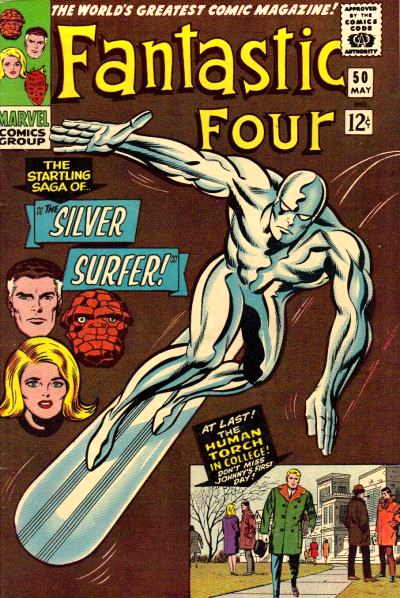

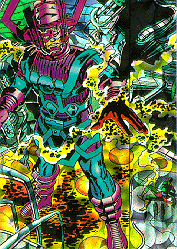

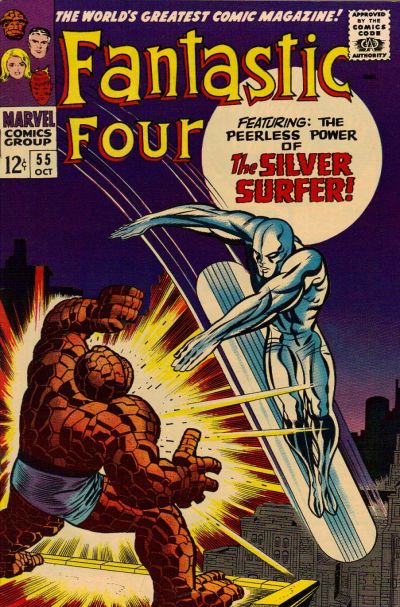

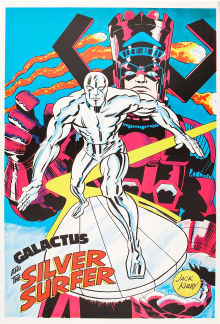

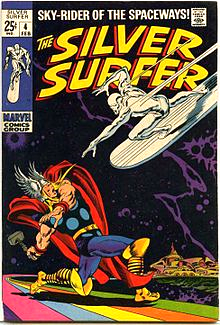

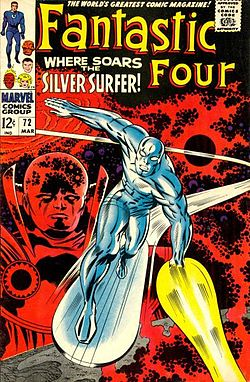

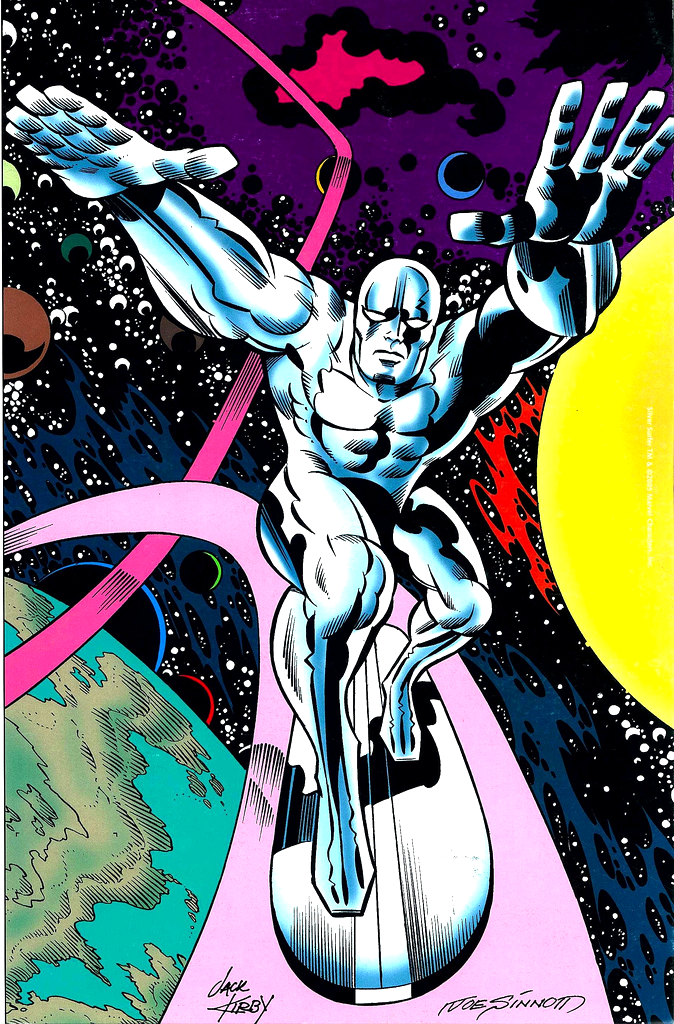

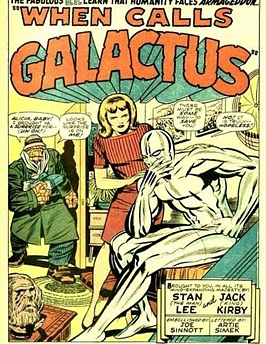

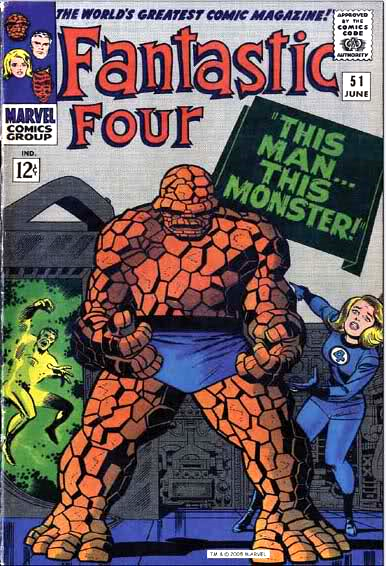

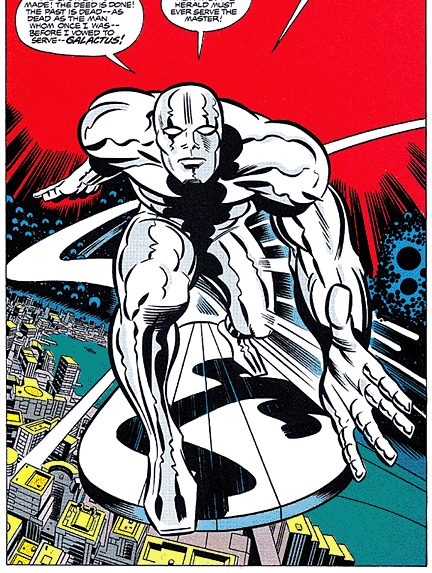

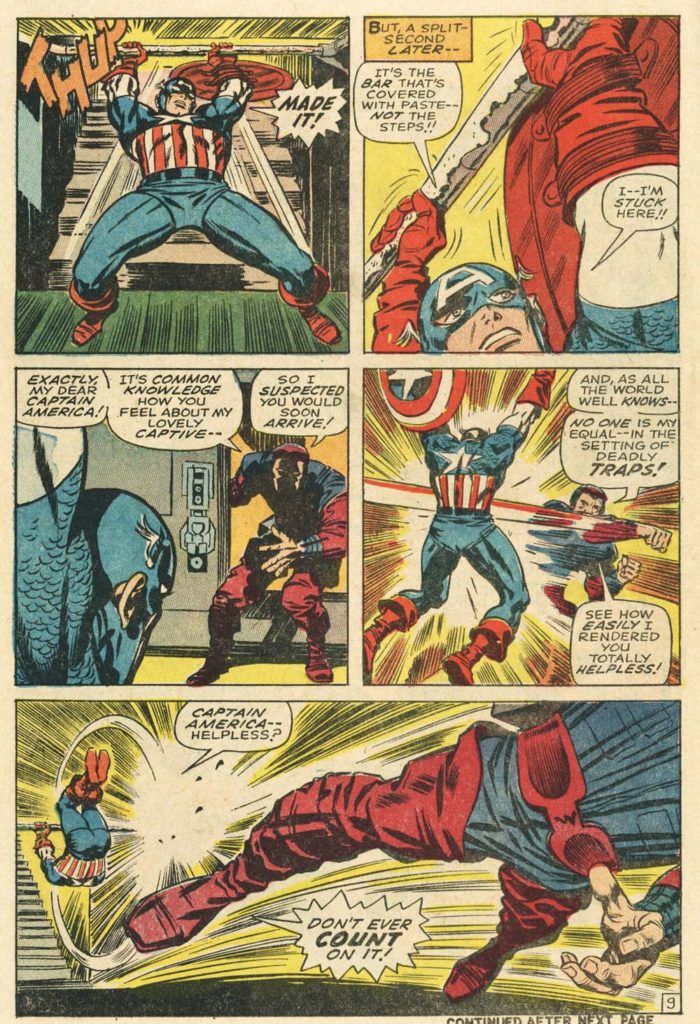

The U.S. was at war with itself. To Marvel this wasn’t enough. They needed a real villain, one that made our little worries seem silly. Suddenly, the Universe was against us. From out of the stars came a monster so vast and omnipotent that the Earth itself was of no more importance than the latest buffet at Golden Corral. This was God, and he was hungry. But Jack’s pacing was such that our danger was doled out a little at a time. First we get introduced to God’s herald, a cosmic being whose job it was to go out and rustle up happy meals for God. Jack’s answer was the Silver Surfer. A chrome covered humanoid who surfed the cosmos like Duke Kahanamoku on the shores of Oahu. Surfing was the hot new sport filling up teen movies like Gidget, Ride the Wild Surf, and Beach Blanket Bingo, while Wild World of Sports began showing surf competitions, and Rock and Roll led with the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean. The sport was graceful, dynamic and centered on the perfect human form.

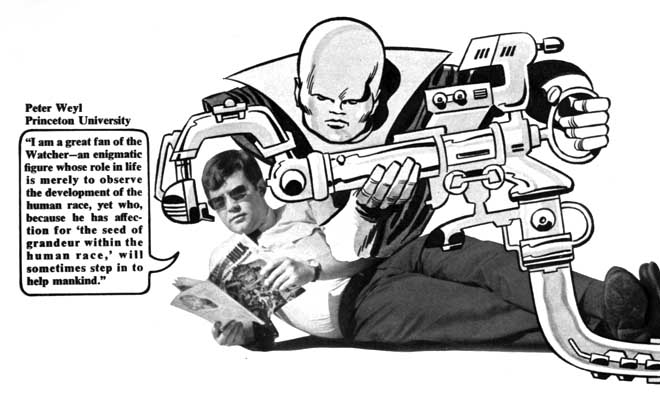

The Surfer was the ultimate comic character—constant movement, no clothes, and could go where no man had gone before. The surf board was a wonderful accessory; it swooped and dove, and lead the action. The first chapter of the saga was the FF vs. Silver Surfer, who treated them with disdain as he checked out this world as a main course. The FF had been warned by the Watcher that the end was near, since Galactus was an unstoppable force. Their every effort against the Surfer was swatted away as insignificant. Yet The Thing strikes a telling blow that sends the Surfer falling into the studios of Alicia Masters.

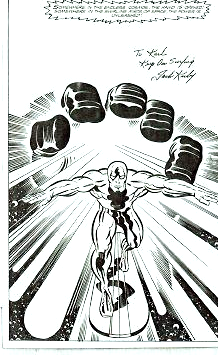

Size – strength – and grace

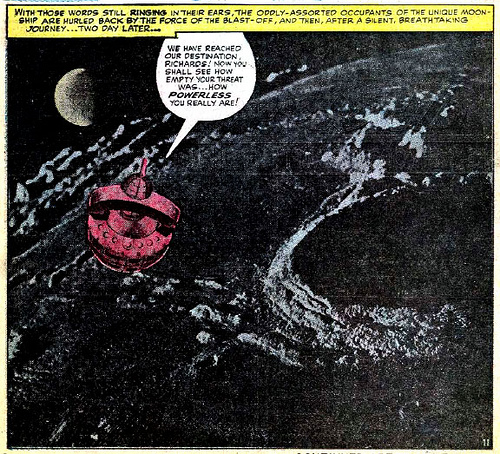

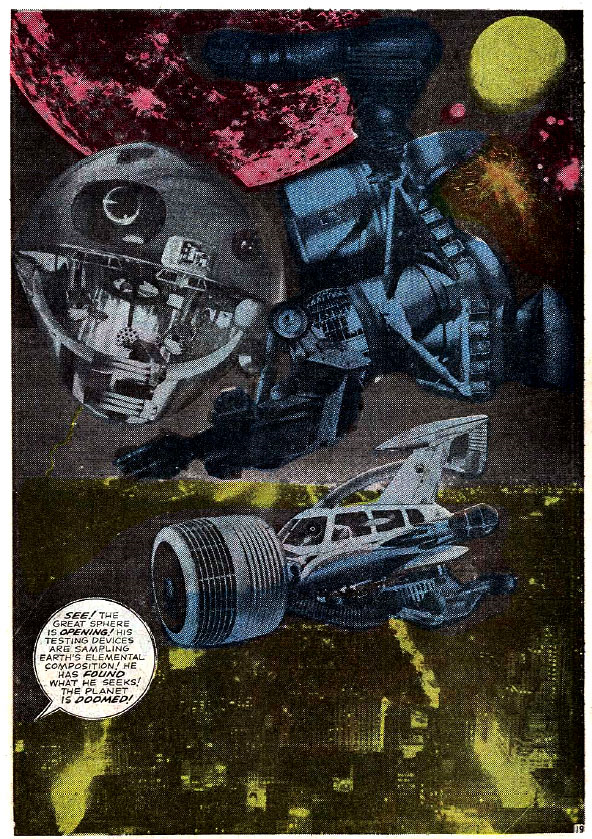

While the Surfer is down, Galactus lands and begins assembling his world-eater. Knowing man has no defense, the Watcher ignores his pledge of no-interference and sends Johnny on a space trek to find a weapon to cause Galactus pause. The other FF members try to disrupt and delay Galactus plans only to be swatted away by his minions.

The Surfer recovers in Alicia’s studio and begins to understand that this civilization has purpose and reason. For once he realizes that he must stand up against his master. The last chapter is the Surfer battling and aggravating his boss, only to be swatted away as easily as the FF had been. Time is running out and even the Surfer realizes he can do nothing to save Earth. Just as Galactus is ready to operate his machines, Johnny Storm returns with a weapon to fight Galactus, Reed takes this weapon—the ultimate nullifier– and soon figures it out and confronts Galactus. Galactus realizes just what this weapon

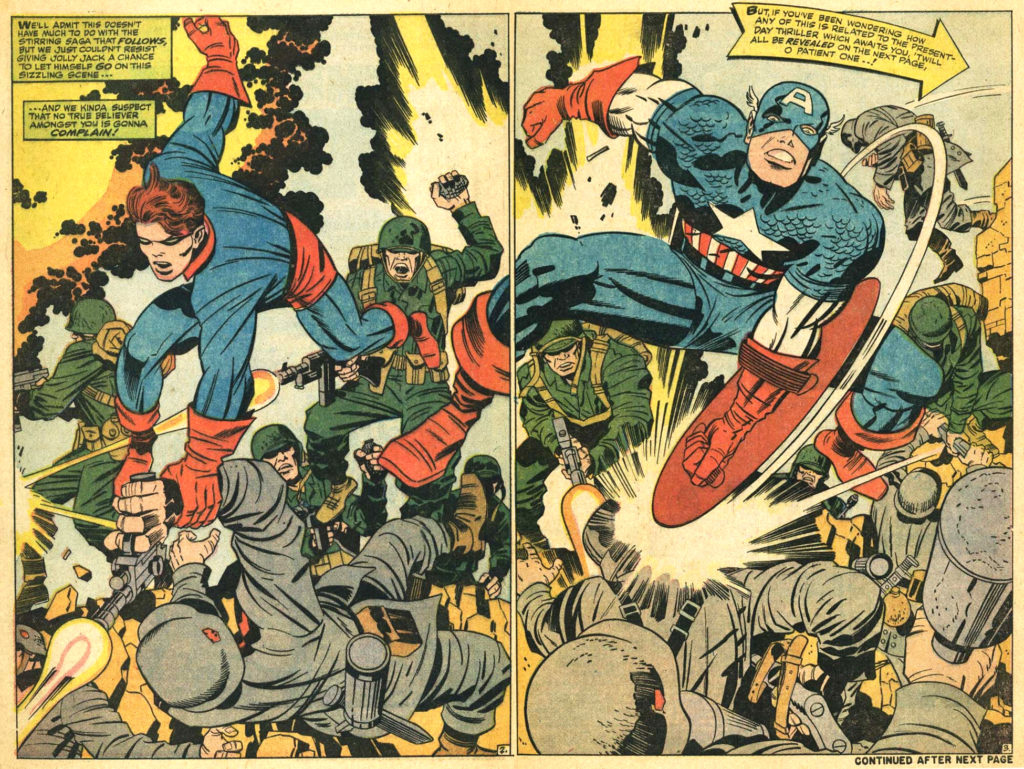

Bite this Michaelangelo – comics x10

could do in the hands of a lower civilization, and backs off. He agrees to leave this world untouched, but as a parting sense of pique, he imprisons his former herald on this world. This mixture of “The Day the Earth Stood Still” and the biblical fallen angel was worlds above anything ever offered to the public before. Jack’s visuals sent this series into a whole new stratosphere. Never had raw power been so explosive and effectively drawn before. His pictures of the Surfer and Galactus surpassed any artistic representation ever done before, Jack’s art entered the realm of the Greats—not even Picasso or Goya would ever present such raw power graphically. It was doing what no artist had ever done. It gave form to unsurpassed power and relegated man to insignificance, yet still showed man at his most godly. Jack took the comic book to a whole new level, so high that it may never be equaled. The Silver Surfer became a symbol of questioning and humanity and haunted belief never seen before in comics. Stan Lee so loved this character that he forbade others from using him. Yet Stan Lee admits that the character was completely created by Jack Kirby. Stan says he was shocked when he first saw this flying icon. Jack had his own ideas, but was usurped from letting him grow. Whenever people talk about what is best about comics, The Fantastic Four #48-50 is always raised. If FF #25-26 stand as the best all-time fight issues, than The Galactus Saga stands supreme as comics as philosophical treatise. My one complaint is that the ending was a little too contrived, Jack had used a similar “Watcher gives the FF an unearthly machine” idea back in The Fantastic Four Annual #3. But it does add another wrinkle to have the Watcher disregard his oath not to interfere. Yet Jack wasn’t finished showing just what comics could do. Jack’s next step was to go to the very soul of what America was about; to take America where it had never gone before. Jack Kirby took comics into the mythological realm of Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth”. Or, as he put it “The Hero’s Journey” Comics had become adult reading.

This isn’t Archie or Casper – Even as action figures they’re mythic

The boys become men

The Beatles let go of the average and took pop music into the mythic when they released Rubber Soul in Dec. 1965. They actively melded pop with Dylanlike lyrics, Byrdlike harmonies, world music and a more sophisticated, worldly, and at times ambiguous message. It seems like a huge step into maturation that left teenage pap far behind. Nowhere Man is a searing portrait of man as an inconsequential character in a larger tapestry. While Norwegian Wood made a single man’s search for love into a cosmic quest of mythic importance. Suddenly rock music became a journey of growth rather than dance steps and stolen kisses. The Beatles threw off their teen mantle and announced they were serious adults.

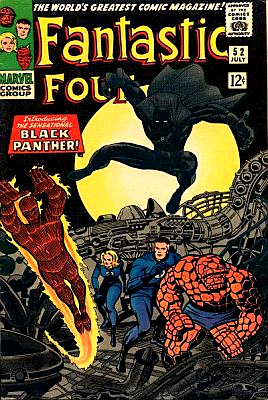

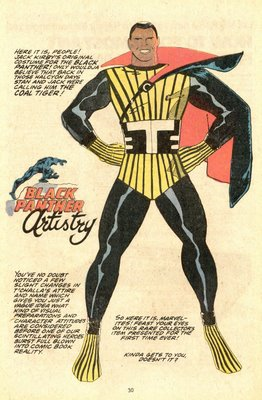

Positive black characters had been a rarity in mainstream comics. Stan and Jack figured it was time to end that lunacy. Their first attempt was in making one of Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandos an African American. Gabe Jones was a bugle playing GI in the multicultural commando unit. His race had been a focal point of several plotlines in the early stories and his bravery and dignity –like Jackie Robinson–never faltered. But Gabe was still a minor character in a book full of unique characters. It was time to create a major character strong enough to stand on its own and where else would Lee and Kirby introduce him other than the Fantastic Four- the comic where most of the important new characters were introduced. In issue #52 July 1966, the Fantastic Four meet up with the Black Panther and his home country of Wakanda in darkest Africa. The Black Panther is the chief of the Wakandans –a small independent country made rich by a natural mineral called Vibranium. T’challa, the Panther’s given name, had used this wealth to promote education and modernity on his small nation and has created a miraculous scientifically advanced country, deeply hidden in the African jungle. But Wakanda had an enemy, and the Panther had to test himself to see if he was ready to take on this enemy. The final test was to see if he could defeat the greatest team of superheroes imaginable. Though he did not defeat the FF, he certainly held them to a stalemate. The idea of heroes testing themselves against each other was a common plot line for Marvel. The heroes fought each other as often as villains. The fight against the villainous Klaw–Master of Sound -would showcase the Panther’s bravery, physical prowess and human decency. He was a perfect fit for admittance to Marvel’s pantheon of heroes. Later we would learn the unique process used at Marvel when we see the actual steps used to create this character. He started out being known as Coal Tiger a very unwieldy name.

Jack always helped out – Intro to a black super-hero

Some have complained that the concept was weakened by making the Panther a super-rich, European educated, African monarch, instead of an American from the inner city. Others disagree saying that making T’challa an African was even braver by introducing a new hero from the emerging continent of Africa, rather than making him an American. Africa had never had a particularly positive image in American culture. More of an after thought used mostly for Tarzan movie backgrounds where the black populace was useful for carrying bags and feeding the lions. Lee and Kirby transformed Tarzan into a black native- the equal to any white hero.

On his blog, Julius Chamblis writes; “The Black Panther provides the visual cue of difference that broke the barrier of white heroic privilege, but not the cultural perspective that created it. Removed from the U.S. experience by national identity, personal history, and individual motivation the Panther’s appearance did not directly address the stifling effect of racial prejudice. The Panther looked different, but like Kirby, his actions affirm his right to inclusion. Like current debates about post-racial thinking, Kirby was not beyond racial identification, he merely attempted to devalue it.”

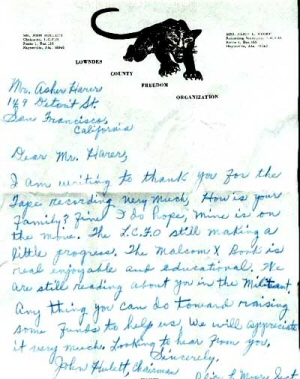

Black panther logo – brother Stokely

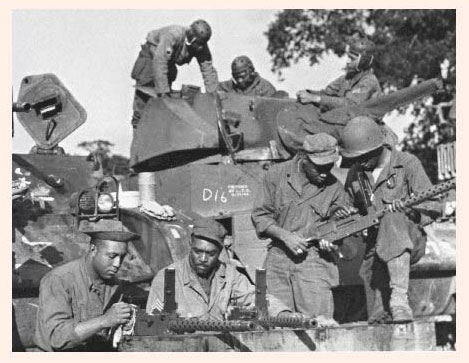

The earliest use of the term Black Panther was for the heralded tank crew fighting in the 3rd Army during WW2. As a World War 2 veteran, Jack was certainly familiar with Patton’s Panthers, The Black Panther all-black tank battalion which led the battle of Lorraine and Metz and was a favorite of Gen. Patton.

The Black Panther symbol predated Kirby’s use of the title. The all-black tank group that led the march into Metz were known as the Black Panthers. Another earlier but not well known use was as the sporting logo for historically black Clark College in Atlanta Ga. It was used in 1965 by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization to help signup black voters in Lowndes County Alabama. Formed by oft-arrested radical Stokely Carmichael and his Students For a Non-violent Coordinating Committee, the LCFO was on the cusp of the rising black power movement. There was national coverage by Life magazine.

A couple months later in Oakland California a group of black nationalists would form a new group espousing Black Power in all things, chief among them the end of police brutality, full and equal black employment, and self-realization of all black people. This group would transform into perhaps the most radical black organization of all. The name of the group was the Black Panther Party. Three black Californians, Huey P. Newton, Eldridge Cleaver and Bobby Seale, asked for permission to use the Black Panther emblem that the Lowndes County Freedom Organization had adopted, for their newly formed Black Panther Party. Stan Lee worried about the name being appropriated by a radical group and changes were suggested. Ideas were passed. But luckily none were accepted. The Black Panther stayed the Black Panther and he became a part of the Marvel Universe.

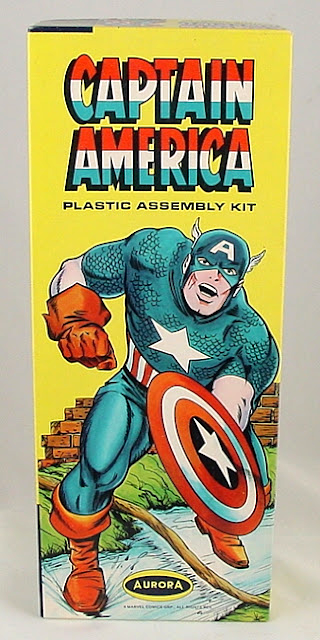

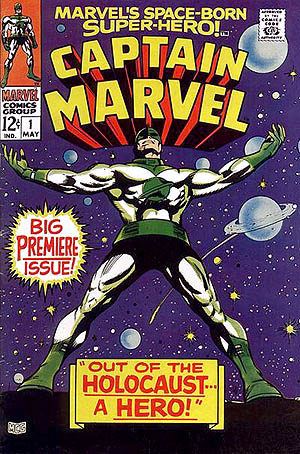

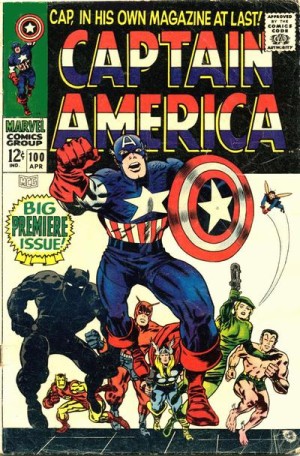

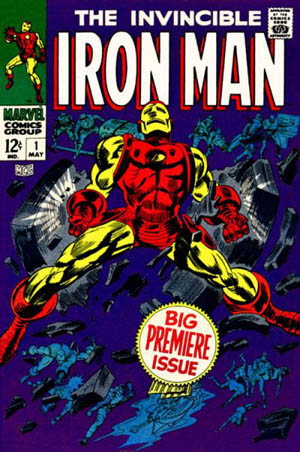

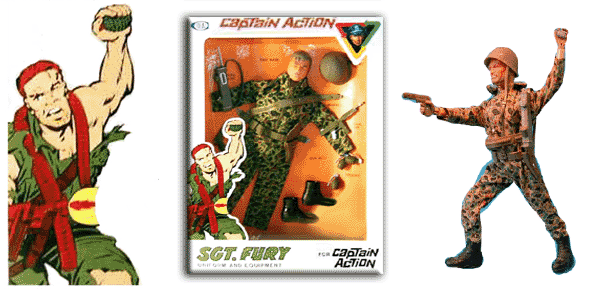

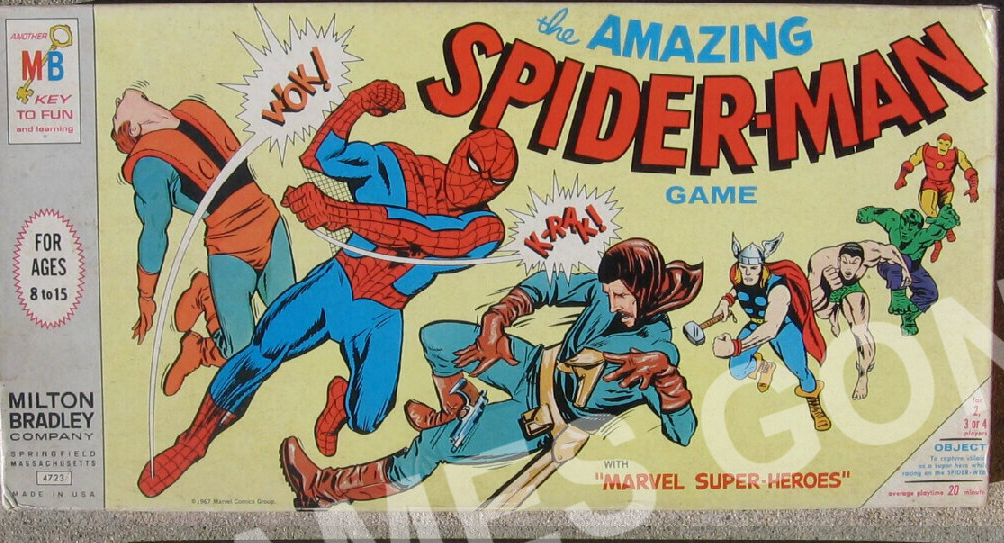

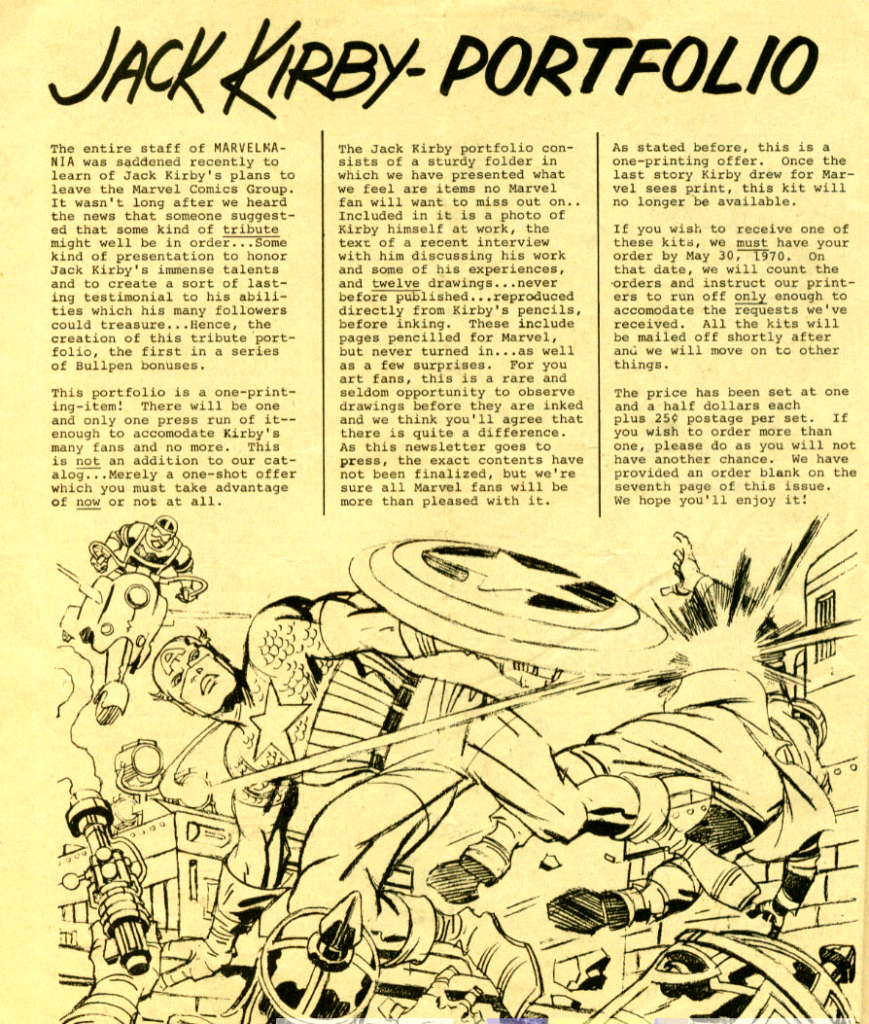

Great first effort but no gloves – Kirby on the cover

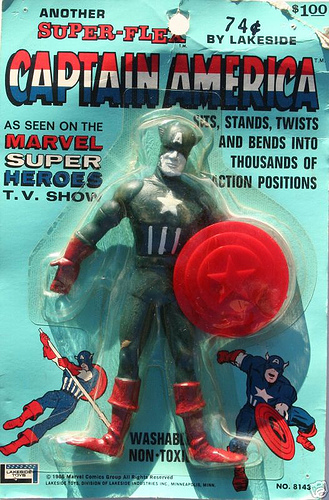

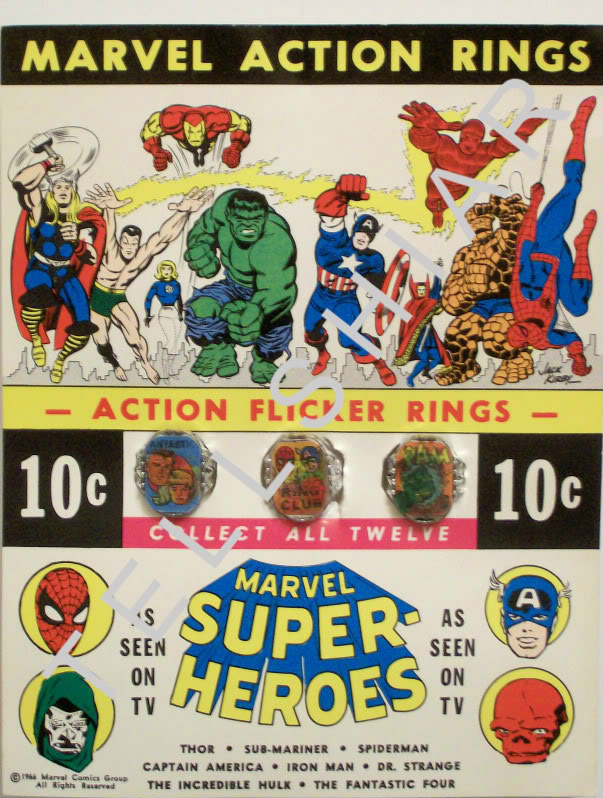

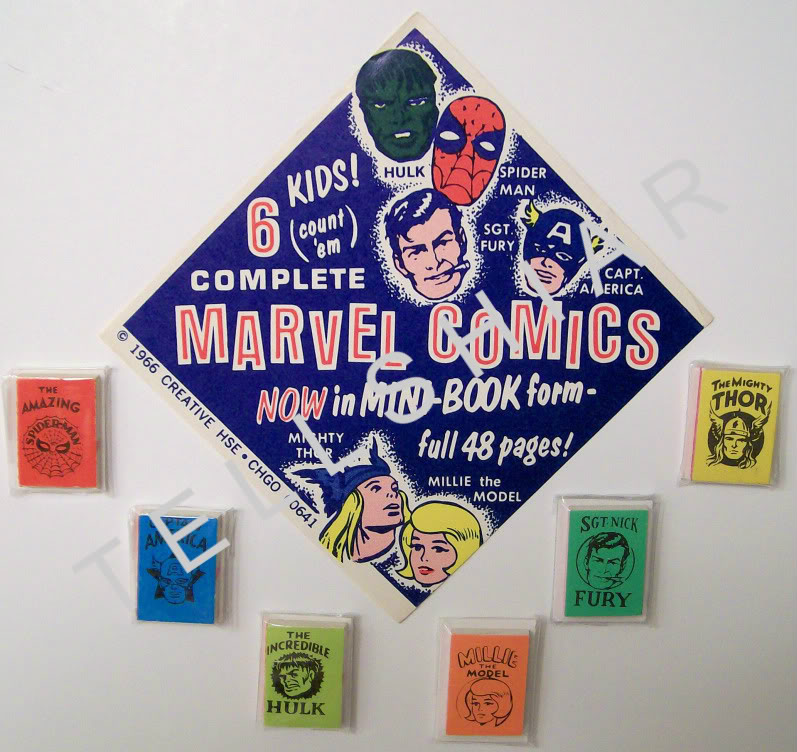

1966 saw the first appearance of a new toy; Captain Action from Ideal Toys continued the evolution of the articulated doll such as Barbie, and for the boys, G.I.Joe—complete with multiple costumes and accessories. Comic characters had crossed over to toys. Action’s gimmick was that he could morph into well known fictional characters as diverse as the Lone Ranger and Flash Gordon. With interchangeable masks, and costumes the Captain could become Superman, Batman, The Phantom, Flash, Aquaman, Steve Canyon, Lone Ranger, Flash Gordon, and from Marvel, Captain America, and Sgt. Fury. Marvel was paid well for the licenses yet never shared with Jack Kirby. Not even for the artwork that accompanied the boxes. Further series expanded on the Captain Action retinue with the likes of Spider-Man and Green Hornet. Captain Action got his own comic book by DC, got his own powers, but lost the ability to change into other characters. As Captain Action’s universe expanded, his son joined in, he even received his own archenemy. (Dr. Evil) The merchandising of Marvel’s characters was exploding upon the masses. And no benefit filtered down to the artists. Cartoons, T-shirts, toys, Halloween costumes, rings, pj’s, puzzles, games of all sort sported recognizable art from the bullpen.

Too generic just a GI Joe costume – no half beard – Should have ripped up uniform

Roy Huggins created and produced a new series Run For Your Life; with perhaps the epitome of the hero with a problem meme. Ben Gazzara played Paul Bryant, a lawyer who has learned he has but two years to live. An anthology style series with each episode in a different location and different people in moments of personal crisis, which the hero helps resolve.

Ben Gazarra legging it

1965 would see the Beatles receiving their own cartoon feature. The adventures were little vignettes based on Beatle songs, plus a couple sing-a-long tunes for audience participation. Produced in Australia, the animation was quite good.

Beatles ham it up

Kirby sells the cartoons

Hysterical local TV host for the cartoons with better costume than the movie Cap – Find this baby!!!

In 1966, Marvel sold the rights of several characters to Gantray-Lawrence to produce cartoons for afternoon viewing. Thor, Submariner, Cap, Iron Man and Hulk hit the airwaves in late ’66 to good response. Spidey appeared in 1967. The animation was of the lowest order–barely stats from comic pages with moving lips and arms and legs. The best aspect might have been the cheesy opening songs lovingly remembered even today. There were a couple commercial tie ins. (note Captain America card blurb) In 1967, The FF got their own cartoon series with much superior production values due to Hanna Barbera’s larger budget. As a publicity campaign for Marvel, they were a resounding success. Jack was taken by surprise with the cartoons. “If I’d known they were gonna do that with it I would’ve demanded to be paid a lot more” Jack went to Martin Goodman and complained. Goodman told Jack that the company wasn’t making anything off the cartoons, they were great advertising for the comics. Kirby had heard that before, but there was nothing he could do about it.

1966 was a good year

At the time, very few managers of pop groups needed to worry about how much money music merchandising could generate as very few artists survived long enough in the pop domain to be a viable investment. As far as Epstein was concerned it was merely good public relations, and any revenue that arose from the sale of Beatles-endorsed products was regarded as merely found money that supplemented the Beatles’ individual incomes from live performances and record sales. “We did our best; some people have said it wasn’t good enough. That’s easy to say with 20/20 hindsight but remember that there were no rules. We were making it up as we went along.” In America Epstein had met the well-known divorce lawyer, Nat Weiss, whom Epstein later asked to take over the merchandising affairs of The Beatles and NEMS. Weiss would later state, “The reality is that The Beatles never saw a penny out of the merchandising. Comic books artists, much less publishers had even less skill and knowledge about the merchandise possibilities.

Look at artwork in background Milton Bradley 1967

Jack’s dream came true! His son had graduated high school, and was going to college. Neal had been accepted to prestigious Syracuse University, the same college that Jack always erroneously said that Joe Simon attended. Neal said that growing up it was considered a Jewish tradition. The son grows up and goes to college; it was never an option, it was expected. But Neal knew of his father’s shame at not finishing high school, and he knew how proud his dad was that his son had surpassed him.

In August 1966 the Beatles headlined a concert at Shea Stadium before 56,000 screaming fans; at the time, the largest attendance ever for a rock concert. Coincidentally, the Fantastic Four and Thor hit perhaps their highest peak of creativity.

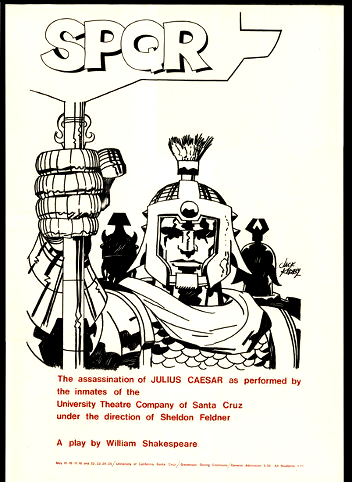

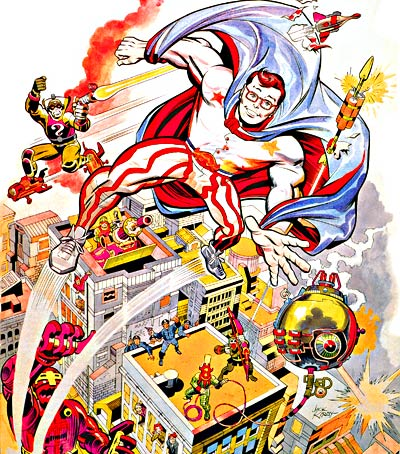

Late in 1966, in another outside commission, Jack drew a promotional poster for a new TV show. Captain Nice was an NBC comedy series featuring William Daniels as a mild mannered police detective who becomes a super hero when he discovers a secret formula. He fights evil in a homemade costume his mother devised. The series was created by Buck Henry, who had also created Get Smart, a spoof on the spy genre. Jack’s part came about when John J. Graham, the Director of Design for NBC, was told to come up with an advertising poster for the new series. John’s son, Bruce was a big Kirby fan, and when his father mentioned the job, Bruce suggested Kirby for the artist. The poster shows the good captain flying over the town while assorted bad guys take pot shots at him. A second drawing showing a close up of three cops looking out a window was added into the commercials. Kirby’s poster was shown on commercials using a fast cut animation style jumping from image to image, promoting the new series.

Chic Stone supplied the inking for the poster, and Kirby colored. Jack rewarded the young Bruce Graham with a personally signed Captain Nice sketch. The series premiered in the fall of 1967. Chic remembers the circumstances. Jack’s sense of timing was sometimes askew. He and his daughter awoke Chic in the middle of the night. He was carrying a huge piece of illustration board which was covered with brown paper. Chic noted; “Jack lifted the brown paper, and I was awestruck by the most magnificent Kirby pencil I had ever seen. It was for NBC and a new show called Capt. Nice. “I couldn’t believe my ears when he asked me to ink it. We negotiated a price, but Jack never knew that I would have been thrilled to do it gratis. When I put my brush to that drawing, it knew just where to go. It was a marriage of pencil and ink. I would love to see that artwork one more time.” The show debuted in Jan. 1967.

Kirby reaches out

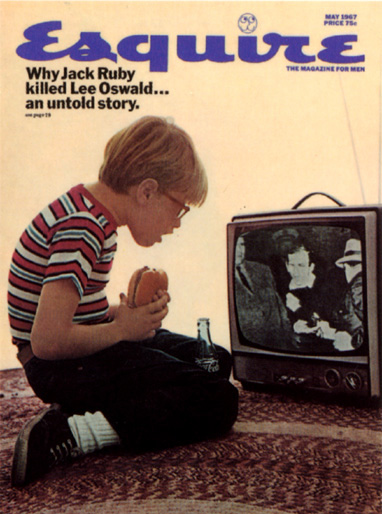

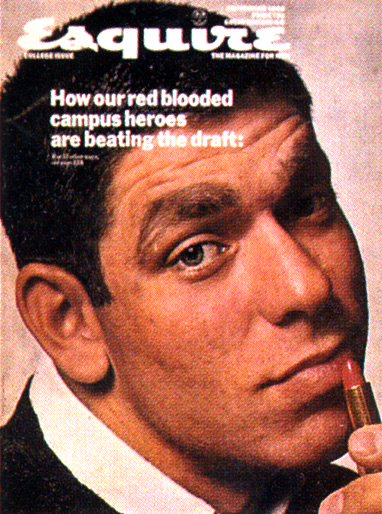

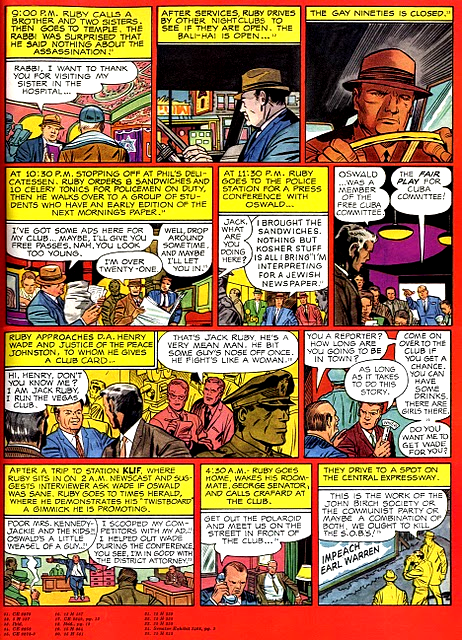

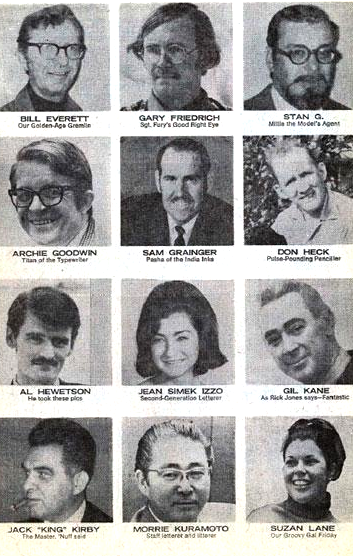

In an outside commission, in late 1966, Jack Kirby had been asked to draw a story for Esquire Magazine. Issue #402, dated May 1967 focused on the Kennedy assassination, and Kirby drew a 3 page tale of Jack Ruby’s life immediately before killing Lee Harvey Oswald. The art was also finished by longtime inker Chic Stone. The art was more realistic than Kirby’s comic art, and he told the story in a straight forward manner with lots of legal testimony added to the text. A few months earlier Kirby had provided some illustrations for an article about the rise of Marvel Publications at colleges. (#394, Sept. 1966) The magazine made quite a fuss about how Marvel had taken over the colleges. There was a mix-up in cover choices and money so the magazine promised Jack more work to make up for it. As usual, Jack got screwed. A later promised job never came to fruition.

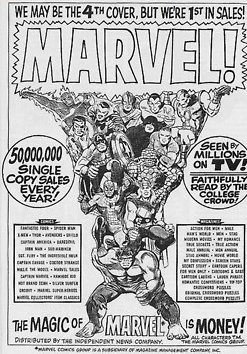

Jack Kirby and Stan Lee had done their job well. At a time of declining readership, Marvel was unique; its sales were rising and the books were reaching markets never imagined. Colleges were going bonkers over Marvel’s characters. They formed clubs and set up classes to study the phenomenon. As the public face, Stan Lee was suddenly BMOC and hosting seminars and talks on major campuses. Stan was on radio, and in newspapers and major magazines, always touting Marvel and himself. Martin Goodman’s once lowly comic division was now spewing forth dollars. Merchandising such as models, and T-shirts were bringing in unexpected profits. Martin Goodman’s company was a red cape flapping in the bull’s faces.

Afternoon cartoons were bringing in new fans, who bought more books. Martin began rewarding the comic division by paying higher, more competitive page rates, which in turn brought in more artists and better inkers, but not voluntarily. When asked if Marvel offered Kirby rate increases, Kirby states: ‘No, no. I had to ask for them. There’s a class system in comics.” “I had to make a living. I was a married man.

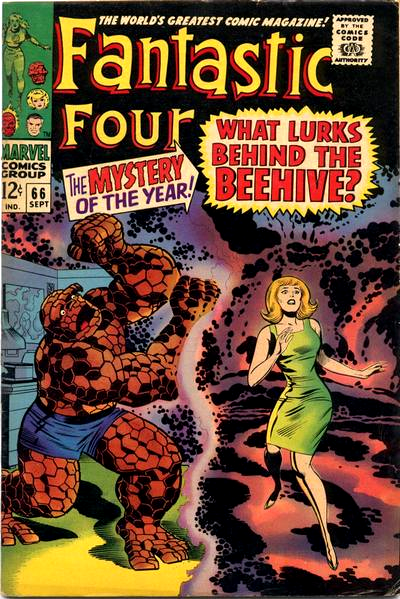

Kirbytech at its pinnacle – Kirby’s super cocoon + child becomes master

I had a home. I had children. I had to make a living. That is the common pursuit of every man. It just happened that my living collided with the times. Circumstances forced me to do it. They forced me. There wasn’t a sense of excitement. It was a horrible, morbid atmosphere. If you can find excitement in that kind of atmosphere the excitement was fear.”

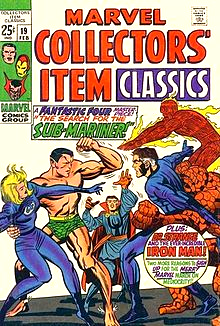

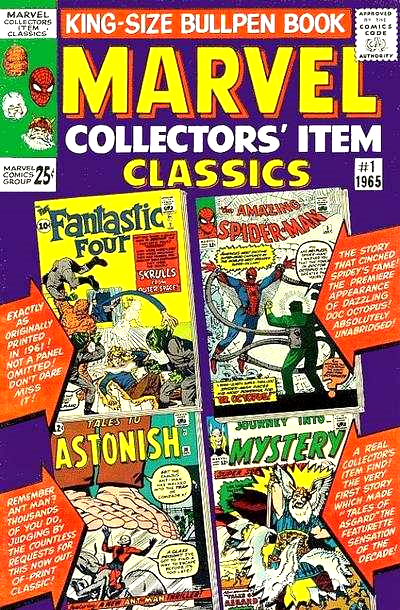

Reprints galore

1968 Marvel gets the gold ring – Jack got tired of correcting covers and working over other artists work for little or no pay

The Marvel method of creating the stories was becoming a problem. Some great artists could not adjust to the idea of self-developing the story from a short synopsis. They came up working from complete scripts, and in some cases were simply not good storytellers. For others they needed a bit of guidance to adapt to the new methodology, and dynamics. Unhappily Kirby began doing layouts to help these artists, such as George Tuska, Werner Roth, and John Romita, to get used to the new in-house dynamic style. There was little or no extra pay for this assistance.

Gil Kane recognized Kirby’s contribution;

“Jack was the single most influential figure in the turnaround in Marvel’s fortunes from the time he rejoined the company … It wasn’t merely that Jack conceived most of the characters that are being done, but … Jack’s point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field … [Marvel took] Jack and use[d] him as a primer. They would get artists … and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby. … Jack was like the Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That’s what was told to me … It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view”

The artists who were creating these plots and stories were becoming disillusioned at Stan claiming sole writing credit. They wanted more money for doing more work. They began questioning and demanding what they thought was only proper. It was their storytelling talents that were selling more books and they wanted a larger slice of the pie. At an earlier time, this would have been inconceivable. The feudal setup of the comic industry made it impossible for the artists to make any kind of demands on the owners. The imbalance of power was so great that even the creators of the largest money maker in comic history were unable to demand credit, or royalties, much less ownership of their creations. Siegel and Shuster, the creators of Superman had been embroiled in a protracted legal conflict with DC comics over the ownership of the Big Guy.

At every turn they had been rejected by the courts. The other artists had kept a keen eye on the proceedings and with each loss, they felt their power diminish. The idea of credits, and royalties, and reprint fees, and copyright to creations was an unimaginable goal. Such was the power of the publishers. Several writers of note over at DC tried to organize, and when the company found out they were summarily released and replaced overnight.

From Kirby in an interview with TCJ:

“The artist is the lowest form of life on the rung of the ladder. The publishers are usually businessmen who deal with businessmen. They deal with promotional people. They deal with financial people. They deal with accountants. They deal with tax people, but have absolutely no interest in artists; in individual artists…They pat you on your head and say “How are you Jackie?” Things like that…..Their accountants are more important to them than you are, and yet you’re making the sales that they depend on. It’s an odd setup, but it exists…..Superman is the classic example, see? All these businessmen are the top of the pyramid, but the entire pyramid is resting on two little stones, and the pyramid denies the existence of these stones because it’s so big. It’s loaded with officials, but the little stones are the ones that are holding it up because that’s where the support is coming from, and I was in the same position.”

But this was the Sixties, a time where every long held assumption was questioned. The first crack was not by the comic artists, but by another group of underpaid and unappreciated artists. In mid-1960, screen writers, represented by the Writers Guild of America went on a long strike.

Mark Evanier; professional writer and comic historian notes;

In 1951, the Guild began to represent the writers of that newfangled thing called television, and in 1955, a number of regional and smaller groups that represented writers’ interests were absorbed and reorganized. We wound up with a Writers Guild of America, West and a Writers Guild of America, East.

From then on, the WGA’s history is largely a series of strikes or threatened strikes, each of which resulted in the establishment of some new right or principle. They won the right to residuals when TV shows were rerun; they won the right to screen credits, setting up a system of rules and arbitrations that stopped the guy who ran the studio from slapping his nephew’s name on your script. The strike of 1960 – which lasted 151 days, making it the longest strike in Hollywood until the Writers Guild later bettered its own record – was the one that secured a pension plan as well as residual payments when a movie was run on television.

The history of TV credits and creative rights and comic books have many parallels. At Warner Bros, the spiritual parent of Martin Goodman’s Marvel, Roy Huggins, the creative genius who guided all the interlocking series, had been constantly thwarted by William T. Orr, the President of WB TV division. Orr once switched the order of the first two episodes of Maverick so that Huggins couldn’t claim credit for creation purposes. Even more famously, Jack Warner deliberately had the pilot to 77 Sunset Strip screened briefly at movie theatres in the Caribbean in order to legally establish that the television series derived from a WB film, rather than, as was actually the case, several books Huggins had written in the 1940s. Since this was not the only occasion on which Warner had found a way to circumvent Huggins’ creative rights, Huggin’s left the studio soon thereafter. Following this experience, he increasingly demanded ownership of all television concepts he authored. By the mid-1960s, he had added this demand into a standard part of all contracts into which he entered.

“I was getting paid my royalty and my fee whether I did the show or not. If I conceived the show, and got it on the air, anyone could produce it and I would still get paid just as if I was doing it . . . That became known as “the Huggins Contract”. Every producer in television would say ‘I want the Huggins contract’, and some of them got it”.

—Roy Huggins, interview with the Archive of American Television, July 21, 1998

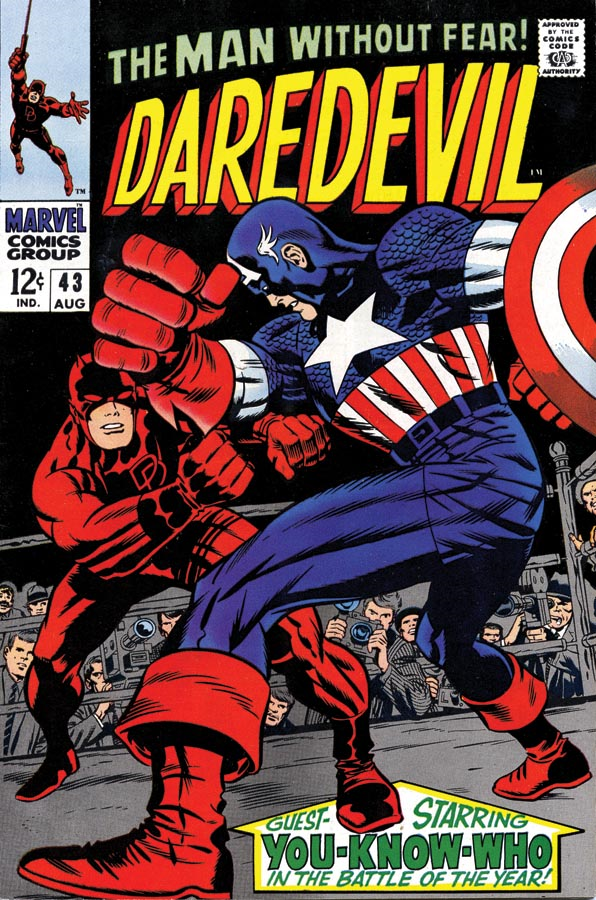

Sadly, comic artists would never unionize, but there was a mounting belief that they deserved more credit and payment for their works. Stan’s personal affection for his artists led to his predilection for listing credits, this would come back to hurt him. Stan was a caring man caught in an uncaring process. First, with the hard headed Wally Wood, whom Stan had heralded on the cover on Daredevil #5 as the next great thing. Wally took to the Marvel method as a duck to water; he personally raised Daredevil’s profile from a low tier character to a top line character with some great stories to match the dramatic costume change. Suddenly the character was allowed access to the top tier villains. Daredevil’s battle with Submariner in Daredevil #7 is considered one of the seminal comics of the Marvel Age. Yet behind the scenes, Wally and Stan were in a constant battle over credits.

If Wally was to plot and pace the stories, he wanted credit as a writer. For Stan’s part the writer credit was sacrosanct; it belonged to him alone, and the money that came with it. It’s important to note that though Stan was the editor, his writing was as a freelancer and he got full writer’s pay for the stories he was co-plotting. There could be no compromise and Wally left after less than 10 Daredevil stories. In an article many years later Wally would write “”Stanley” came up with two surefire ideas… the first one was ‘Why not let the artists WRITE the stories as well as draw them?’… And the second was… ALWAYS SIGN YOUR NAME ON TOP… BIG!!” And the rest is history…Stanley of course became rich and famous … over the bodies of people like Bill and Jack. Bill, (Everett) who had created the character (Submariner) that had made his father (uncle) rich wound up coloring and doing odd jobs. And Jack? Well, a friend of mine summed it up like this. “Stanley and Jack have a conference, then Jack goes home, and after a couple of month’s gestation, a new book is born. Stanley gets all the money and all the credit… And all poor old Jack gets is a sore ass hole.” This was the first of many breaks in the façade of a Merry Marvel bullpen, but the fans never knew. Stan’s bullpen bulletins spun a tale of nothing but jocularity and solidarity among the artists. Yet Stan’s bullpens made superstars out of the artists.

If the Emperor’s new clothes were beginning to fray at Marvel, the Beatles were suddenly naked. Despite a three year run of unparalleled chart dominance and critical acclaim the public had turned against them. A manufactured American band knocked the Beatles off the top rung. The Monkees were Hollywood created to take advantage of the new sounds and popularity pioneered by the Liverpool lads, but dismayingly they started to sell more records. Even worse, an offhand, but not untrue, remark in a small magazine interview by John Lennon comparing the Beatles to Jesus Christ had escalated into a full blown revolt by Churches and youth groups that started to burn Beatles records and ban them from radio play. Cynthia Lennon in her biography says. “In an interview John likened the Beatles to Jesus Christ. His truly honest assessment of their popularity offended the God-fearing, clean living Americans who lived in the Bible belt of America. His views were perhaps misconstrued. John was very bewildered and frightened by the reaction that his words created in the States. Beatle albums were burnt in a mass orgy of self-righteousness indignation. Letters arrived at the house full of threats, hate and venom. Finally to try to squash the revolt John Lennon offered a somewhat tepid apology. “If I had said that television is more popular than Jesus, I might have got away with it. It’s a fact, in reference to England, we meant more to kids than Jesus did, or religion at that time. I wasn’t knocking it or putting it down. I was just saying it, as a fact and it’s true, more for England than here. I’m not saying we’re better or greater or comparing us with Jesus Christ as a person or God as a thing, or whatever it is, you know, I just said what I said and it was wrong, or was taken wrong, and now it’s all this!”

Shades of 1955

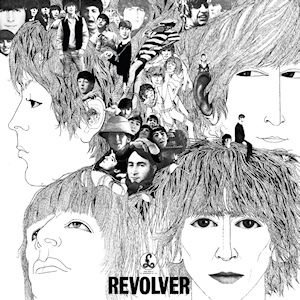

It helped that in August of 1966 they released their most refined album. Revolver is their finest collection of songs minus some of the over production of their last couple albums. But cracks had formed. John went off to Spain to film a movie while George left for India to visit the Maharishi and study with Ravi Shankar. At an art gallery in London John Lennon meets Yoko Ono. Suddenly the single minded purpose of the lads gave way to individual needs. Egos were taking over. I tend to think this is a natural progression seen in many successful collaborations. Two being one can only last so long.

The racks were rocking in Aug. 1966

Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby had followed keenly the rise of Marvel, and they constantly hit up Goodman for a raise in page rates. Marvel had slowly risen close to the industry leader DC. They also noted that their graphics were being used to sell T-shirts, toys, clubs, games and even bed clothing, and that they got nothing extra for their graphics. They confronted Stan and Martin and were told that when the comic division started making a bigger profit, that they would be taken care of.

Steve Ditko had built Spider-Man into Marvel’s best-selling book. Steve was also in the process of developing a very rigid personality enthralled with the philosophy of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism. The black and white nature of this belief made it hard for Steve to compromise, and Stan increasingly found it hard to work with him. This is ironic as it was Ditko whom Stan loved writing for most of all. Ditko, like Wally Wood, also demanded credit for what he considered the writing since he was providing the plots and pacing for the book. Spider-Man was too important to the line and for once Stan relented and in issue 26 the credit for co-plotting was added to Ditko’s name. Despite this band aid, pretty soon things became so bad that Stan and Steve no longer talked and all communications were passed through a go-between.

To give an example of Stan’s disconnect with the anger of the artists not receiving proper credit, the consummate pro Dick Ayers tells of his growing animus with not getting credit and confronting Stan. One day Dick approached Stan; “Stan, I think I should be paid for co-writing your stories….you don’t even give me credit…you just sign your name as writer!” To which the unconvinced Stan replies. “My-oh-my you do have an ego! Okay, I’ll add a couple bucks to your page rate! But not your name as writer…”

Even on the girl books cracks were forming. Stan Goldberg, the longtime Millie the Model artist told interviewer Jim Amash; Stan would drive me home and we’d plot our stories in the car. I’d say to Stan, How’s this? Millie loses her job.” He’d say, ”Great! Give me 25 pages.” And that took him off the hook. One time I was in Stan’s office and I told him, “I don’t have another plot.” Stan got out of his chair and walked over to me, looked me in the face, and said very seriously, “I don’t ever want to hear you say you can’t think of another plot.” Then he walked back and sat down in his chair. He didn’t think he needed to tell me anything more.”

For Kirby’s part, he was old school. Credits were nice, but he worked to care for a wife and four children. As long as he could get higher page rates, the secondary demands would stay on the back-burner. The Marvel method was its own reward for it meant that Stan would mostly leave Kirby alone to take his series where he wanted them to go. Jack’s trips to the Marvel offices dropped to once or twice a month.

The most aggravating part was Stan’s little niggling demands for page redos and doing layouts for competent artists who Jack felt needed no help from him. Worse yet, Kirby got little extra money for redoing and laying out pages. Kirby’s pride also started taking a hit as more and more, in all the articles and interviews it was Stan who was credited as the main creative force on the books. Kirby knew how the system worked, but it smarted when in an interview for the New York Herald-Tribune, Stan was presented as a creative visionary and Jack Kirby as a drooling toady in an ill fitting suit. This so enraged Roz that she personally called Stan to demand he get a retraction of some sort. Stan played the aggrieved and ignorant party. Jack soon became tired of being told by Stan to redo his first cover and come up with a new one. The time it took to make a new one was never compensated by the company. Similarly, whenever he went into the studio, Stan would gladhand him to correct parts of other artists covers for no money. Stan’s charm was running thin. And Jack’s ego was roiling.

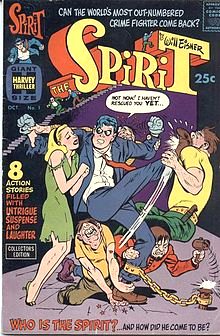

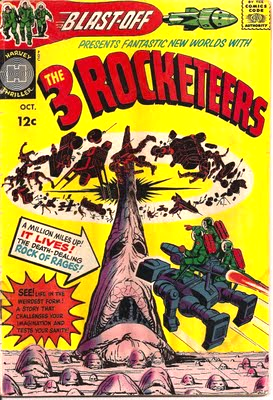

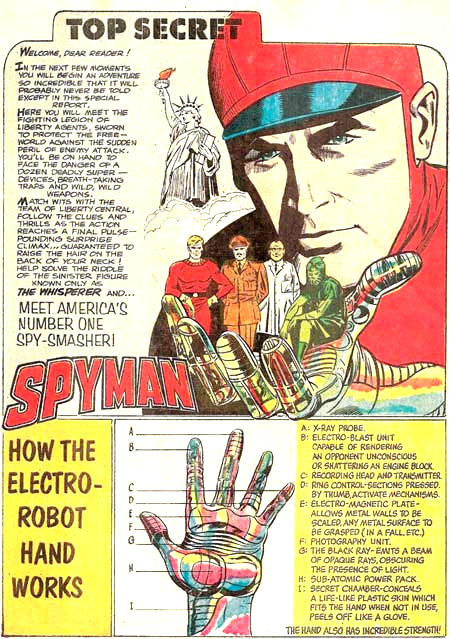

In 1966, Harvey Publishing contacted Joe Simon about jumping on the bandwagon of Jack Kirby at Marvel. Harvey had Joe put together a couple issues that featured heavily Jack Kirby art from old Harvey inventory. In Blastoff, Joe assembles stories originally scheduled for Race For The Moon #4 with a Kirby collage type cover. In Fighting American Joe put together some unpublished Kirby stories from Fighting American and padded it with old inventory plus a newly drawn story by George Tuska. The requisite Kirby cover is a doozy. Joe also put together two issues of Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Joe also created a new super hero universe for Harvey, hiring a young newcomer named Jim Steranko to help create it. Jack was competing with perhaps his best art ever, Moody, strong, and an endless imagination.

The songwriting style of Lennon/McCartney had started out as a seamless symbiosis of the two artists; a smooth combination of style and inspiration, a blending of strengths and weaknesses. But with the release of “Can’t Buy Me Love” a song written solely by Paul, the team began a new process and a friendly rivalry began where they began writing separately and fighting for who would get the next single. This competition also affected George Harrison, who was becoming a strong songwriter himself. Yet he always found himself the odd man out when it came to singles. He did manage to usually get one song per album, but never the prize. It wouldn’t be until 1969 and the release of “Something” that Harrison’s talents would be rewarded. The competition led to an outpouring of superb songs. George Martin’s producing never allowed it to get out of hand. In the studio all players added in bits that added to the final product.

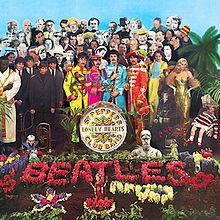

In 1967, the Beatles released their most lavishly crafted LP yet. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band would become the record against which all others would be judged. Its success was so astounding, and the production values so leading that none could ever live up to it. Even future Beatles albums couldn’t live up to it so that they specifically chose a lower fidelity retro rock and roll feel for their records.

Rock and roll kitchen sink – awe inspiring

At the same time Jack and Stan released the ultimate FF books. #66 and 67 has Jack give the world the ultimate creation, Him. Rising from a manmade cocoon, the creation is so above humanity that it realizes it must leave mankind alone. Though not by Kirby, this creation would become the super being Warlock. No creation was ever left behind. It was not without problems. Stan missed Kirby’s meaning and changed the whole story. It lost a lot of the deeper philosophy of Kirby’s original story. Some say it was Kirby’s stab at spoofing the new absolute philosophy of Ayn Rand and her “perfect heroes”. Stan’s ideas would continue long after Jack’s involvement with the character. Him made an appearance over on Thor, but it turned into a typical battle royal and an unfulfilling ending. It would be a couple years before he was reincarnated as Warlock.

Stan was not a fool, he knew he couldn’t afford to alienate Kirby, so Jack’s credit were upgraded almost to an equal of Stan’s in the Fantastic Four when it switched from separate and unequal to a combined “Produced by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.” Several more times Jack and Steve would remind Lee and Goodman about their promise to share in the greater profits, (perhaps in response to the Wall Street Journal article) only to be shined off with further promises.

Stan Lee has been quoted far too many times not to believe that there is a thread of truth to it. “It’s a little trick I learned; instead of paying people money, I gave them a little credit line in the books. This went on for a couple years before they got wise.”

For his part, Steve Ditko had finally had enough; the quiet, philosophical bachelor made a choice, and after 39 consecutive issues of Spider-Man, two annuals, and dozens for Dr. Strange, he gave notice. After Woody, this was strike two. Stan Lee to his everlasting shame still denies knowing why Steve Ditko left, while Steve made it very clear in a telephone interview with comic journalist Bob Beerbohm in 1969 that he was tired of being put off by both Goodman and Lee over the subject of residuals.

“Steve Ditko told me and my friend Steve Johnson that he and Jack had been promised royalties if their new creations took off. They were told by Martin Goodman (picture a fellow putting his arm around the back of your shoulder, voice sounding very sincere) “Don’t worry about a thing if the books sell well, we’ll take care of you.”

That ‘we’ included his relative, Stanley Lieber, long time editor of Goodman’s comic book division. Just a division, mind you. Goodman was also a major publisher of a lot of those “men’s adventures” magazines popular to a lot of vets back in the 50s and 60s plus yet other areas to make a buck in.

When the first merchandising on Spider-Man, by this time already one of the main titles, came along, Steve started making noise about the extra dough. So did Jack. They were told that the company was still not making enough money, to wait. Promised contracts never seemed to be completed to be signed, carefully verbal in nature.

By early 1966, Steve walked, he said to us, and he urged Jack to come along.”

One might think with two strikes, Stan would become more cautious about losing the artists, but I think Stan began believing his own press. He thought that it was he that had imbued the Marvel Universe and the artists were simply his tools, despite leaning more and more on them. Increasingly Lee’s input dwindled to where there were some stories with not even a basic plot by Lee. On a Sgt. Fury story Stan told Dick that he had no ideas for the next issue. Dick drew a blank also and it was Dick’s wife Lindy who came up with the plot. When Dick suggested a onetime credit for Lindy, Stan summarily dismissed it. Another time, on a story without any Lee input, Ayers was adamant about receiving the writing credit. Lee was just as adamant that he would not receive the writer credit, but instead, Lee would give Ayers credit as letterer and Ayers would get that additional pay; Lee would still get the writer’s credit and pay. Lee laughed this off and claimed that Ayers was getting an ego without realizing his own, this is a screaming indictment of how the work place relationship at Marvel had devolved; and then to try to buy him off with a couple gold pieces. A victim of their own success; once again Kirby and the other artists were reminded just how low their place was in the Corporate scheme. The ones doing the creative work received the least reward.

One of the newcomers was John Romita, an artist who had made his name with DC’s romance books. He started working over Kirby layouts on Daredevil. He was given the Spider-Man series after Steve Ditko left, and changed that book from a dark, serious series into a lighter, more reader friendly series and the fans responded. One day, he took Jack to the Playboy Club for lunch. There John told Jack of a long ago tale. During the Crestwood days, Joe and Jack would advertise for new artists to work for them; mostly as inkers and “in-between artists” who could take some of Kirby’s layouts and expand them to fit a story. Young John Romita responded to one of the ads, and was given a penciled page to ink as a test. John took the page home and inked it; looking at the page he was disappointed, so he did it again and again. Never satisfied he threw it away and never returned to Simon and Kirby. “I told him I chickened out. I should have brought back the inked page and let him (Kirby) tear it apart. I would have have learned more, but I was embarrassed at the work I did”. I said to him “Gee Jack, we could have been working all those years,” and he said “That’s a shame John, I could have turned you into a dynamo.” “If I had worked with Jack, if I had the guts to go back, I would have been a different artist, a much more confident and freewheeling artist” Romita lamented.

To help replace the lost work from Steve Ditko leaving, Stan hired an old pro from Atlas days. John Buscema had come to comics in the mid-fifties while Atlas still had an in-house bullpen. With the changeover to all freelancers, and the Atlas Implosion, John had abandoned comics in a huff. Stan could now offer John full employment and stability. But John’s skills had rusted up from non-use. His first work was stiff and uninspiring, John worried if he could cut it. From an interview in Jack Kirby Collector;

JB: “I would not have been able to survive in comics if not for Jack Kirby. When Stan called me back in 1966, I had one hell of a time trying to get back in the groove. You can do illustration, you can do layouts, but that doesn’t mean you can do comics. It’s a whole different ball game. Stan gave me a book to do; I think it was the Hulk. I did a pretty bad job – Stan thought I should study Jack’s art and books so he gave me a pile of Kirby’s comics. Well, everybody was given Jack Kirby books! (laughter) It was the first time I’d seen his work. I started working from them, and that’s what saved me.

TJKC: What did you learn from them?

JB: “The layouts, for cryin’ out loud!” I copied! Every time I needed a panel, I’d look up at one of his panels and just rearrange it. If you look at some of the early stuff I did – y’know, where Kirby had the explosions with a bunch of guys flying all over the place? I’d swipe them cold! (laughter) Stan was happy. The editors were happy, so I was happy.”

Dick Ayers also tells of a might have been story. Starting out, he would take his portfolio from publisher to publisher looking for work. Getting nowhere, his list was down to two more services. He was close to the Vin Sullivan studio so he dropped in. As fate would have it, Vin recognized the talent and immediately put Dick to work; a partnership that lasted a long time. Getting work, Dick decided to ball up his list and toss it. One last quick look and Dick realized that the next name on his list was the Simon and Kirby studios. He always wondered about the what if. Did he have what it took to work for Simon and Kirby. He did get the chance to work with Joe Simon years later when Joe resurrected the old Black Magic title, and his career was always linked to Jack when Marvel came to the fore. The comic biz was always a small world, where most talents eventually meet and connect.

Comic readers come and go; they age and move on to other pursuits; girls, jobs, cars, girls, school and the other symbols of maturation, did I mention girls! It’s been said that every five years produces a new class of comic readers, unaware of the legacy of the artform. It had been just about five years when Marvel started reprinting their original tales. They sold well as the rise of Marvel’s fandom meant that most new fans had never really seen the earliest Kirby and Ditko/Lee stories. While Goodman and Lee were happy with the results, the artists were livid. Perhaps even more odious than the lack of credit was the reprint fee controversy. The idea that the company can make unlimited new money by reusing existing art without ever reimbursing the artist was never even broached. Why should the companies continue to make new money using existing art, yet not offer the artists, new money? In the movie and TV industries, this subject had been resolved for quite a while, always in the artists favor, residuals for reruns were mandatory, but the comic industry was a dinosaur, and reprints had long been a common way of cheap revenue. Worse, the artists were in reality competing against themselves for sales off the stands.

From the AFTRA rule book:

Residuals are paid to actors when their performance is used AGAIN, or in a new way that was not intended when you originally worked. For example:

* A re-run of a television show

* A feature film that was released in the movie theater, but is now being released on DVD

* A television Movie of the Week that is now being sold on DVD

* A second use of a commercial (or a third use, or 300th use!)

* A TV series that is now being used on the internet as a “Webisode” (a.k.a. “new media”)

* A TV series that is sold into syndication

* A network TV show that gets shown again on a cable channelThe really great news? This process goes on FOR LIFE. You will continue to get paid smaller and smaller amounts each time the film is shown, forever.

The rights won by actors had no impact on the graphic artists.

It wasn’t until the 1990’s that some artists won the right for residuals, and even then, not for all occasions. It certainly wasn’t back-dated for the original 1960’s books. DC paid some small residuals for merchandise to Jack in the 1980’s, but it was done as a gift, not a right.

Dick Ayers was so devastated by the constant reprints of his work that he began sending Marvel a bill for each reprinted story-which Marvel ignored! Once Dick confronted production Manager John Verpoorten about the increase in reprints and John made it clear. “the old stories sell as good as the new!” Dick retorted, “I should be paid for each reprinted page! How am I to support my family with such a low income while Marvel profits reprinting and selling my reprinted art- and don’t share that profit with me?!?” Dick Ayers quit working for Marvel, and was later blacklisted for suing for those same reprint fees–he lost.

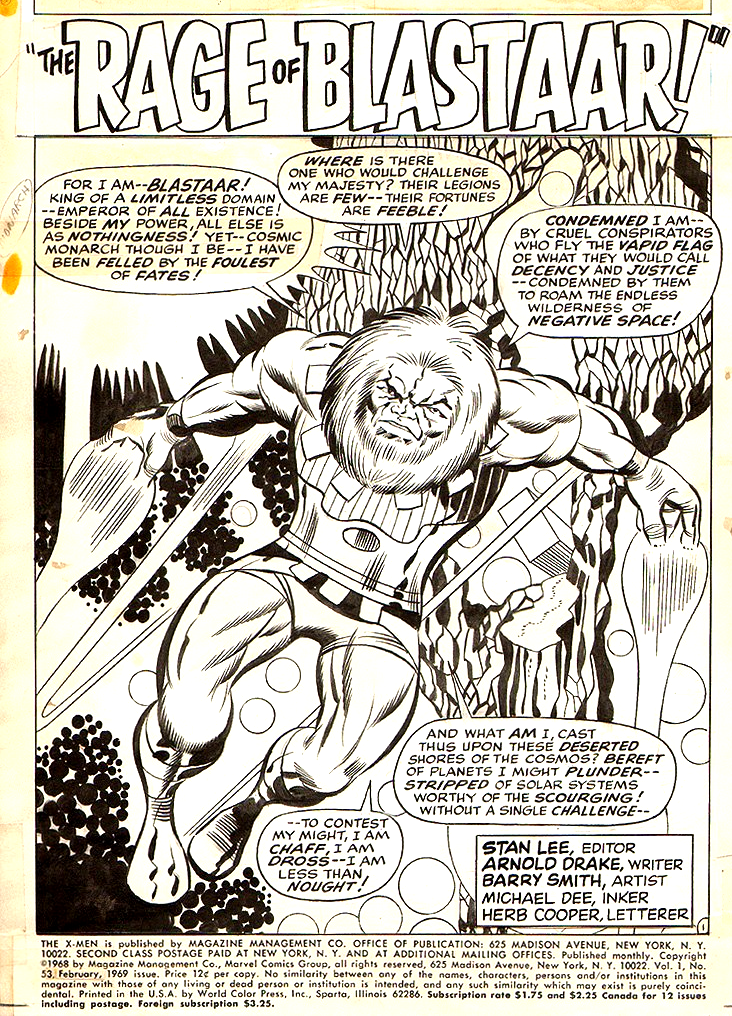

The company laughs while the artists seethe – New cover-same story by Kirby – Lots of Kirby for 25 cents

Of all the artists, it was Kirby who was most affected by the reprints since he had contributed so much of those early stories, but Jack was stoic and just kept working in the dungeon-as he called his basement studio. And the work was the best ever done for comics-by far. The FF hit a pinnacle of unequaled creativity that covered about 20 issues where every issue brought forth new characters and concepts that would resonate for years. Stan was more astute. “Jack is a storyteller in pictures. After a while, I only had to give him a couple of words on what I thought the plot would be and he would do the whole thing. He was so inventive, He kept getting new ideas, and whenever he’d get one he’d put it in the next story. And I’d say “Jack, save that for the next issue or the one after that. It’s too much.” Instead of new books, Kirby kept introducing new heroes in the Fantastic Four. The Inhumans, the Silver Surfer, the first black hero, the Black Panther, and Him-soon to be Warlock, as well as new villains such as Blastaar, Galactus, the Frightful Four, Klaw-the master of sound, and Quasimodo- the villainous machine made man. Perhaps the pinnacle was reached in what became known as the Galactus trilogy (FF#48-50) which introduced a new villain- Galactus- a godlike being to whom the Earth held no more significance than a McDonald’s Happy Meal. His herald, (the Silver Surfer) who searched for just those planets that might satiate his master, is transformed by the loving humanity of Alicia Masters and turns against his master to try to intercede in the Earth’s behalf. Even the power of the Surfer is nothing to Galactus and he continues his work to drain the world of all life essence until the Human Torch returns from an intergalactic search with a weapon of such magnitude that even Galactus relented, but not before banishing his traitorous herald to remain imprisoned on the Earth.

Enter Norrin Radd – Silver Surfer gets the prize

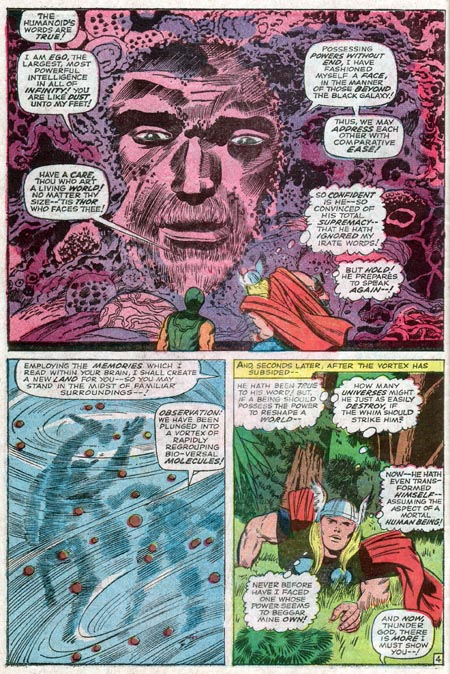

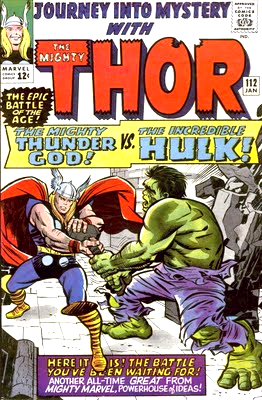

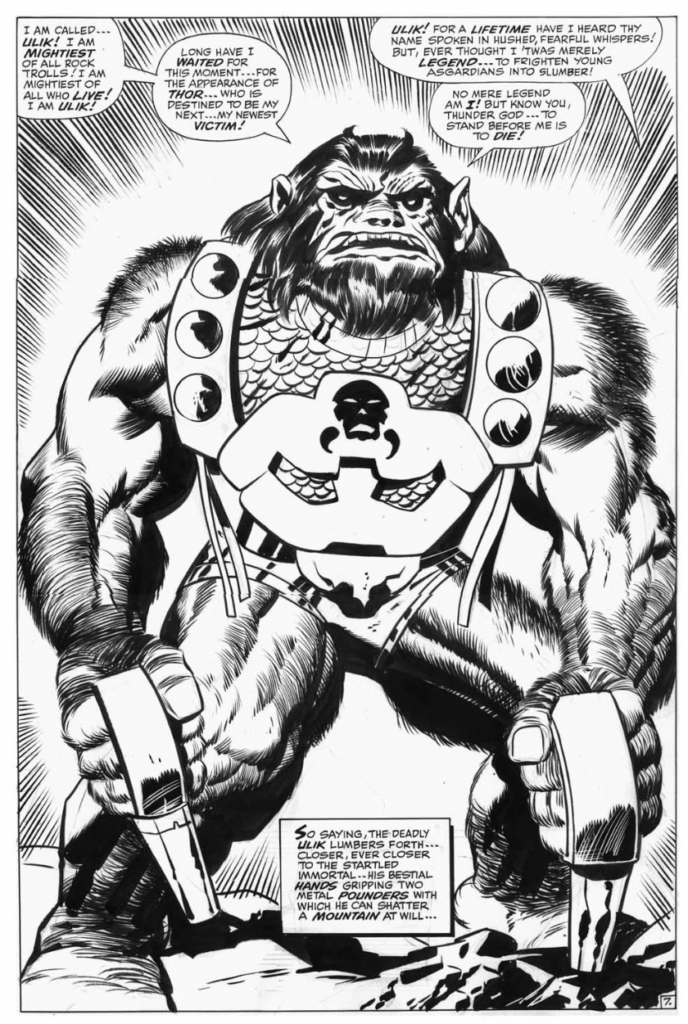

No series could ever come close to matching this outburst of creativity found in the FF -except possibly Kirby’s Thor. During this same period Kirby introduced Hercules, Tana Nile, Ulik, Ego-the living planet, the High Evolutionary, and in perhaps the grandest story arc ever done, the Ragnarok epic with Mangog. Not to be outdone, Captain America would reunite with the Red Skull, and meet Them, Batroc-the leaper, Modok, the Sleepers, and Zemo. It was such a burst of creation that Stan Lee became lost for words in his feeble previews of coming attractions blurbs. “I’ll create a concept just to keep from getting bored.” Kirby noted when asked in an interview with The Comics Journal about this ramped up cosmicology.

TCJ: …back in ‘65’and ’66, you started to get on this mythology-fantasy kick. Who was responsible for that –you or Stan?

KIRBY: “Both of us, in a way. I researched it and gave my version of it, and Stan gave his version of it. Stan humanized it in a way where, for instance, I might be concerned about Thor’s relationship to the other Gods, I might bring up a Ulik or I might bring up something out of the wild blue yonder, like the Oracle-that great big thing which nobody knew anything about. I try to fathom it myself. And Stan would come back down to Earth and find Thor’s relationship with Earth people. In other words, we go up and down the spectrum always trying to find something new in it.” In another interview Kirby explained: I’ve been a student of science fiction for a long long time, and I can tell you that I’m well versed in science fact and science fiction. I’m 71 years old and so I’ve seen all this new conception. I used to read the first science fiction books, and I began to learn about the universe myself and take it seriously. I know the names of the stars. I know how near or far the heavenly bodies are from our own planet. I know our own place in the universe. I can feel the vastness of it inside myself. I began to realize with each passing fact what a wonderful and awesome place the universe is, and that helped me in comics because I WAS LOOKING FOR THE AWESOME. I found it in Thor. I found it in Galactus.”

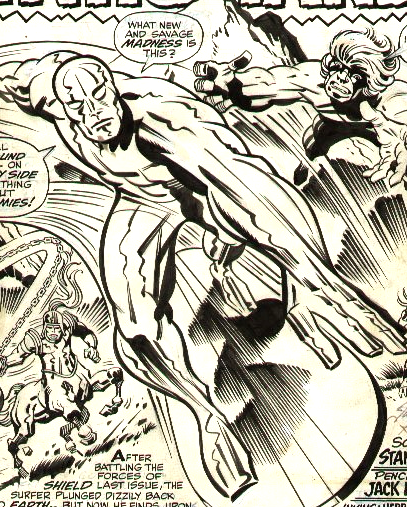

As glorious as the concepts, the execution was even better. To many, Kirby’s art in the mid-sixties has never been rivaled. That bulkiness that Jack began adding to his characters now reached an apex. His characters looked like they could leave footprints in solid concrete.

Yet they maintained a sense of movement and fluidity. It was unparalleled in its power, grace, and grandeur. Kirby created universes, and constructs of such dynamics and imagination that they are still the measure which all else is compared. Stan Lee in perhaps his greatest accomplishment paired Kirby up with his finest corps of inkers. The Fantastic Four got Joe Sinnott, the most precise, clean and expressive inker to ever grace a Kirby pencil, with all deference to the great Wally Wood. Vince Colleta, the most maligned inker to ever work on Kirby added an illustrative texture and archaic feel to the mythical milieu of Asgard that is still unrivaled. And Syd Shores, and Frank Giacoia both gave Captain America a grit and sheen combined with a Golden Age solidity and weight that worked well with Kirby’s more Earth bound warrior. In a three year period, Kirby equaled the grace and power of Alex Raymond’s space opera, and the mythical epicness of Hal Fosters Prince Valiant, and the exotic locales and thrill-a-minute adventures of Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates.

Jack found the awesome and showed it to us

Though it’s doubtful that Kirby had consciously mimicked his childhood idols, it is a might coincidental. Kirby became the artist and inspiration that the next generation of artists would emulate. When asked about his changing styles, Kirby replied. “You’re goddamn right, and it might change again if I live that long.” “I won’t live or die by what any man made up. I live or die by what I see, that’s all.” “I feel I see a lot because I analyze a lot. I see the same things you do but maybe I get more time to analyze it whereas you might not. So I sit and think and it’s as simple as that.” “I feel I’m God because these things are living or moving to my concepts. Good or bad, that’s how they come out. I can even punish them by erasing them but I’m not that mad yet. I like to make them as perfect as I can, and I feel now that’s what God is doing with us.”

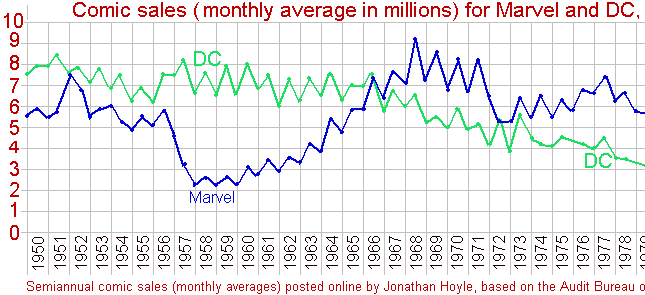

The reward for all this hard work was obvious. Sometime in 1966-67 Marvel took over as the sales leader among comic publishers. While DC was mired in a decade long slump, Marvel’s sales had improved on a consistent 45% angle. This improvement started just as Jack Kirby had entered the picture. There really isn’t any other way to look at it except as starting when Jack Kirby took over. The rise started in the late 1950’s, before Stan and Jack collaborated on the super-heroes. Marvel as a company hadn’t made any changes that could account for the rise except for hiring Jack Kirby. The most noticeable increase started in the monster books; it really took off with the coming of the super heroes. As Marvel grew, the new artists continued this trend. The one constant was Kirby’s other worldly imagination, which kept the books fresh and new.

Jim Steranko talked about Jack and a memorable meeting with Jack while Jim was working for Joe Simon at Harvey.

“The more we talked, the deeper my understanding became of the man and his work. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Kirby efforts clearly transcend writing, illustrating and storytelling. The enduring quality of his comics and career are testimony to the multi-faceted approach apparent for half a century.

From Blue Bolt to the Forever People, Kirby functions as architect, satirist, and philosopher, as a pop media visionary with extraordinary range and depth.” ….”Like the great artists of every age, Kirby and his work has continued to change and mature, appropriately evolving through each decade. He has changed too. By example, he has proven the imagination knows no bounds by taking us to countless fantastic worlds that would not exist had Kirby not created them. He has spent a lifetime turning two-dimensional comic book clichés into surprisingly fresh situations with wit, intelligence and style…..The shockwave of Kirby’s creations will continue to resonate as long as heroes resist oppression and champion the quest for freedom. Perhaps more than any other 20th century artist, Kirby is responsible for a modern mythology that has touched millions of readers on every continent. No artist has ever done as much, as quickly and as masterfully as the man who has justifiably been christened by his peers. “The King.”

In the late 60s, a young artist wanna-be from Detroit had contacted Kirby for a local fanzine. Greg Theakston would later graduate high school and move to New York. Once there he would join Neal Adams little band of crazies. Yet he would always maintain contact with Jack. Jack seemed to enjoy this contact with the younger generation and he shared many confidences with the young man. Greg Theakston would take it upon himself to showcase Kirby as the primal genius of the comic book industry. His reproductions of Jack’s earliest work and his personal reminiscences helped form Jack’s legacy. It’s hard to understand Kirby’s place without Greg’s publishing. Jack rewarded his loyalty by giving him inking jobs, and a chance to paint Kirby’s covers.

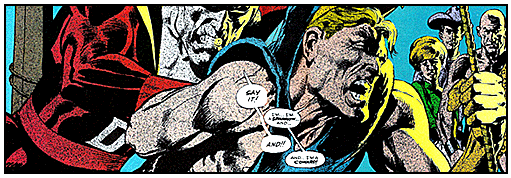

Kirby’s pencils were entering a new phase of expressionism. Musculature that defied human description, Machines and buildings that defied belief, but they worked. In fact, JimSteranko asked Kirby about his machines and said; “Jack confirmed my suspicion that every weapon, vehicle and device in his stories was designed to work, not merely appear workable.” Most of the Kirby iconography that defines the greatness of Jack Kirby can be first found in this later period. Kirby krackel, Kirby dots, Kirby squiggles, Kirby architecture, Kirbytech as well as the most expressive forced perspective ever. Kirby’s costume design was at its most expressive. Kirby began experimenting with collages-using them as backgrounds for other dimensions and worlds without limits. His women were a perfect mixture of grace and strength, unrivaled in their power, beauty and femininity.

His multiple Universes dazzled the young minds and ignited the imaginations of all the readers. Just as Kirby’s lithe, loosey-goosey characters and Art Deco backgrounds came to symbolize Golden Age comics, his new blockier, more powerful figures with full psychedelic vistas and photo montage came to represent the Marvel Age of comics. This stuff wasn’t found in nature—it emanated from Kirby’s brain.

Strength, looseness, and a pyschedelic dot pattern background – all symbolism and surrealism

Jim Steranko inked Kirby on a few issues of Strange Tales. He recalls, “Unlike many pencilers, Kirby put everything on the page, yet never even short-cutting black areas with the common practice of indicating them with an ‘X.’ He felt a page was incomplete until a certain dramatic and visual balance was achieved. His pages rippled with integrity, crackled with the kind of power that was best expressed by his pencil line as it touched the board—much like a jazz musician blowing an improvised passage. Capturing the magic of that pencil line in ink is almost an impossibility, especially by another artist with a different sensibility,”

Mike Esposito had inked over everybody, and was considered a top talent. Yet he had his problems. He told an interviewer;

“Kirby was dynamic. When I inked Kirby, Stan would bawl me out and say ‘What are you doing? You’re drawing a real nose, it’s not supposed to be a real nose! They’re two little holes.’

“I was taking things too literally, and was trying to draw a real nose, but that was not Kirby.

“Frank Giacoia came by one day and said ‘Mike, just paint by number.’

“Frank inked all that stuff. He said ‘Don’t try to create your own look, just follow the lines, and it will all fall into place like a jigsaw puzzle.’ He was right. You don’t draw on top of Jack Kirby, because it won’t work.”

John Romita, the consummate pro, who became art director explains at a Kirby panel about inking Kirby’s new expressionistic style.

“Jack Kirby did a formularized, direct, explicit pencil technique. …a lot of pencilers are so vague and do three lines and give you (the inker) a choice of one. Some of them do greys on their pencils and you have to decide how to make them black and white. Jack Kirby never left you that problem. Every single thing was there, including Kirby’s Cosmic Crap.

Even the colorist understood majesty

I remember all the cosmic effects he made. I used to spend days trying to explain that to some of my trainees at Marvel, how to do that and what the pattern was. Because they thought if they did a lot of big, black blobs, they were going to get Kirby’s cosmic effect. And they couldn’t understand. I said, There’s a pattern there. Just look for it. There’s a pattern he used. He’s not creating black spots. He’s creating white areas by putting black where there’s no light” Nobody understood it. Jack did. He created it. He made it work and he made it graphic, and he could produce it in a split-second, without any mess and clogging. It was wonderful stuff. But what Herb (Trimpe) is passing up is that only a few guys, like he and Frank Giacoia, and Mike Royer could understand that explicit direct black and white style. And the only reason I put Vince Colletta down was because he used to put a lot of lines where there didn’t need to be lines. There didn’t need to be a lot of hatch (cross-hatching) All he needed to do was the blacks that Jack inscribed. It was a diagram, it was a natural gold mine, and a lot of guys overlooked it.”

But it wasn’t just the changes that Stan Lee begged Jack to do, plus the layouts and corrections for others. Stan also had a habit of having his studio art director John Romita make silly changes that Stan thought would help the storytelling. The problem was more that Stan couldn’t always follow Kirby’s plotlines.

John grudgingly remembers;

“ Stan wasn’t down on anyone’s artwork. He never changed anybody’s artwork because he disagreed with the artwork; it was the storyline that he changed. The artwork had to be changed because he was changing the storyline. I changed a lot of Jack Kirby, but not because the artwork was wrong. Stan wanted a new expression, or he wanted to change the position of a character, because he was always changing a storyline. What Jack would send in was always invariably different than what Stan had asked for. Stan would write another story, and I would have to do changes to make it work. People think that because I was art director, I made that judgment, but I never did. I wouldn’t have changed Jack Kirby’s artwork if my life depended on it! But when Stan wanted a change in story, I had to change the artwork. I changed Colan, I changed Barry Smith — did you ever see those embarrassing Barry Smith covers with my faces on them?”

Romita, in an interview was asked about when he became the official art director, his answer is very enlightening.

Romita replied; “It was never official. It was a handshake. It was so unofficial that Stan used to be paid as art director. I never got a penny for being art director.

That’s not a very good arrangement at all, replied the interviewer.

“I used to say that Stan would give titles instead of salary increases. He would call a person an assistant editor, but not give them a raise. He used to give us nicknames instead of raises. [Laughter.] That’s why I got so many nicknames.” (Stan would say the same thing)

So Stan was getting the editor’s salary, the writer’s salary and the art director’s salary, while having others do at least two of the jobs.

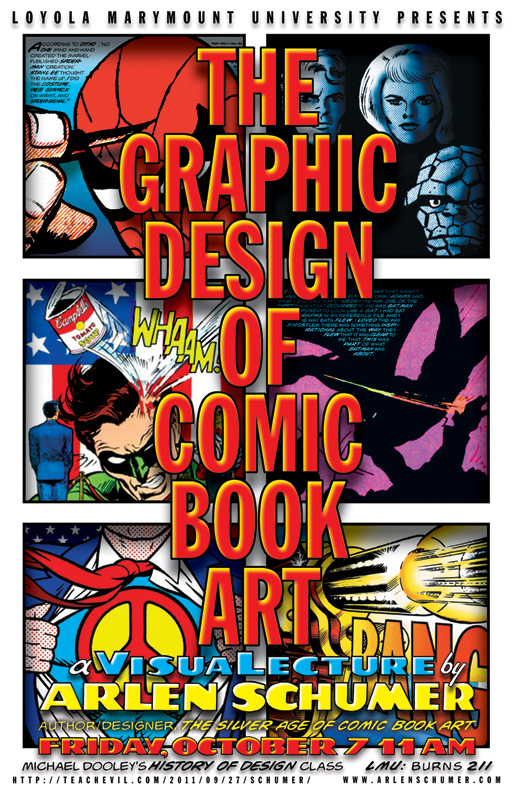

Arlen Schumer noted art designer, critic and pop culture observer notes;

Kirby was probably inspired by the first quasar photographs published in scientific journals around 1965 to create his patented energy field of patterned black dots that has become affectionately dubbed “Kirby Krackle.” One of the first major displays of Kirby Krackle emanated from Galactus’ hands in the full-page panel found in FF # 50 (May 1966). But it was seven months later, in FF #57 (Dec. ’66), that Kirby codified all of his graphic power and energy ideas (including his trademark background “burst” lines) in the four-panel sequence of Dr. Doom transferring the Silver Surfer’s “power cosmic” to himself, climaxing with the staggering full-page portrayal of a triumphant Doom, aswirl in Kirby Krackle, astride the fallen Surfer: the most dramatic definition, in a single image, of victory and defeat in the history of comics – if not art itself.

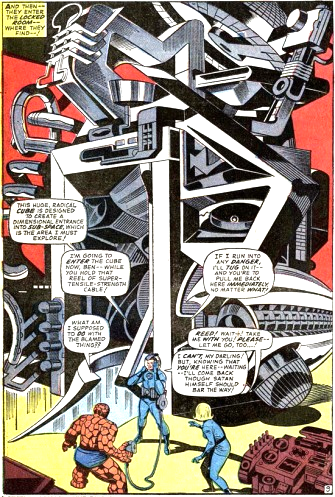

Kirby’s machinery – a.k.a. “Kirbytech” – was never drawn to look functional; the moebius strip-like masses of mazed metalwork that were a mainstay of his oeuvre were simply stylized designwork, as much a recognizable architectural motif as Alexander Calder’s mobiles or Louise Nevelson’s abstract, sculptural boxes. The endpapers of the Jack Kirby sketchbook (Jack Kirby’s Heroes and Villains, Pure Imagination, 1987) are perhaps the purest examples of the graphic design of Kirbytech, unfettered by figures and word balloons.

Decorating Kirbytech – and everything else, whether it be flesh or fabric – was the omnipresent Kirby squiggle, a vertical stroke interrupted by, well, a squiggle. It could add shine to machinery or sinew to musculature; it was Kirby’s singular, graphic signature. The oscilloscope-like arrow shapes that Kirby frequently employed as well some say were influenced by the Art Deco designs prevalent in Kirby’s environment during his formative years, while others maintain they had an almost Aztec-like design quality – though how the son of European immigrants raised on the Lower East Side of New York City without a college education could’ve come up with those remains a mystery.

Character made for squiggles

Another recurring graphic device of Kirby’s that bore no relation to reality were his shadows and spotting of blacks: artfully placed circular, curved and arched shapes that served to balance the black and white compositions of each panel and page more than they delineated accurate castings of light. Kirby always bent and exaggerated reality, like his square fingers and blocky knees, to suit his wishes as an artist; yet when he wanted to portray the verisimilitude of real life – like in his autobiographical “Street Code” story (Argosy, 1980), or any of his Earth-interludes in Thor – the results were quietly breathtaking, the converse of his cosmic panoramas.

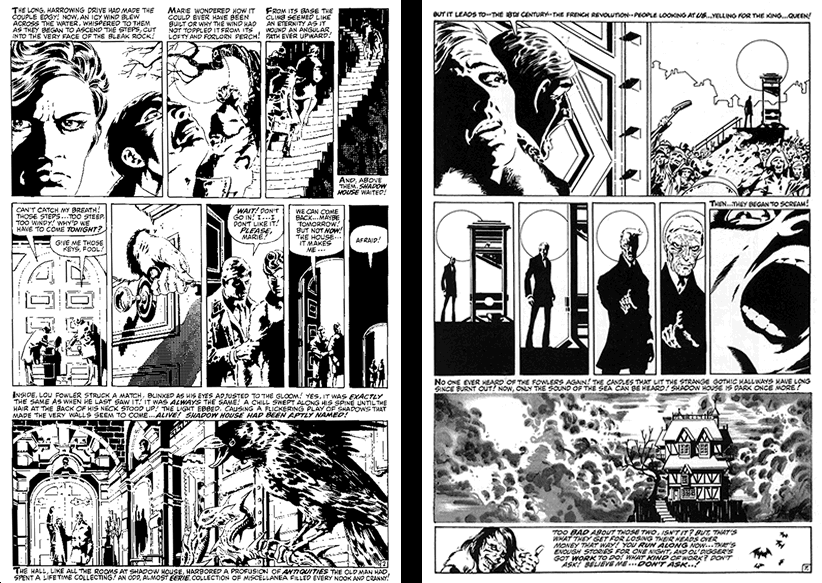

As a graphic storyteller, Kirby never really bothered with panel shapes and page designs that broke out of the traditional box format; he believed more in the proscenium-arch theory of comic book storytelling, in which what is designed in the interior of each panel is more important than the exterior shape of the panel itself. That stays constant – like a stage’s proscenium arch – so that the reader focuses more on what is happening within; the story itself. At a time when firebrands like Jim Steranko and Neal Adams (and Will Eisner before them) were radically redesigning panels and pages in the late Sixties to make them more “cinematic,” Kirby was content to let his drawing do the talking in standard four-, five- and six-panel pages, interspersed with random full-pagers and double-page spreads, which were often spectacular.

The abstract photo collages that Kirby started to do in Fantastic Four around 1964 (his first collage cover was FF #33, Dec. ’64) were startling to his readers, for they were unlike anything any artist had attempted in mainstream superhero comics before; astute comic historians could recall photo collages used by Eisner in his Spirit stories and Harvey Kurtzman in the pages of Mad years prior, but they were nothing like Kirby’s. His were freewheeling, frenetic photo-fests that often subverted average objects, culled from consumer magazines as popular as Life Magazine, or as edgy as Playboy, into imagery as otherworldly as his own drawings. “Collages were another way of finding new avenues of entertainment,” Kirby said in an old interview. “I felt that magazine reproduction could handle the change. It added an extra dimension to comics. I wanted to see if it could materialize, and it did. I loved doing collages – I made a lot of good ones.” Kirby’s Krazy Kollages led to the development of groundbreaking original designs like the alternative dimension the Negative Zone in the FF and Ego, the Living Planet in Thor

These are among the graphic designs of Jack Kirby that rank him as high on the totem of 20th Century American Graphic Design as his hyperbolic drawing ranks him in the Comic Book Hall of Fame. To consider the latter without the former is to overlook some of the more uniquely artistic attributes that do indeed make Kirby “King.”

In the late ‘60s, fandom had begun to organize. What was once myriad points of light became a focused laser. From local comic clubs, Comic Cons sprang up where fans could meet, and buy and trade old books, and talk to industry pros about their favorite characters. Kirby found his audience. Jack reveled in the attention and popularity of his creations, but something sinister caught his eye. During the Golden Age it was customary for the publishers to backstock the old original art. After it was printed it was thrown on a shelf. Joe Simon tells about how during rainstorms the ceilings would sometimes leak, and they would throw original art on the puddle to sop up the water. Flo Steinberg says that they would store it and occasionally she would grab an armful of art and old scripts and toss them out. Stan frequently gave pages to subscribers and advertisers as gifts. Yet with the growth of the conventions, prized art was even more valuable than the books. Jack noticed on many dealer tables pages of his original art-selling for good money. Fans would bring over pages for him to sign, and Kirby questioned where they came from. Dealers would quickly hide pages when Kirby approached. Many stories began circulating about huge caches being secreted out of Marvel’s offices and offered on the street like drugs to junkies. Other staffers finding stacks by the back door that they “liberated” from destruction. Kirby asked Stan for his artwork back only to be refused blaming the need and habits of the business as the reasons. Jim Steranko also noticed, and when he asked Stan, he was also refused. Jim was not one to take no for an answer. Jim confronted Stan Lee and told him that he was going to the tax board and tell them about this valuable stash of artwork that had no taxes paid. Stan quickly told Jim that he could pick up his artwork after the process was done, but Marvel would not help in any way. Kirby persisted to no end. Jack’s art leaked out in droves. Kirby learned that some of the inkers had received a share of the art, but not Kirby himself. The camel’s back started bending.

Copyright law allowed for the creator of a property to regain control after 28 years with a couple exceptions. The claimant must have been one of the authors, and he must not have been an employee or designated as a “work for hire” freelancer. Joe Simon, who had kept busy doing Sick Magazine and the occasional Harvey editing job, decided that he wanted to reclaim Captain America. It was Joe’s claim that he had created Cap in 1940 while freelancing for Timely. For Timely’s part, they claimed that Simon’s participation was done as an editor and covered by the “work for hire” clauses so Joe was prohibited from making a claim. In 1966, hoping to catch onto the planned Captain America film, Joe sued Marvel and in 1967, the case was moved to the Federal Courts who rule on copyright matters. Kirby could not join Joe in this claim as he was a salaried employee at the time Cap was created. According to Joe, Martin Goodman called Jack in and told him that Joe was suing for Cap and was trying to cut Kirby out of the loop. So Martin promised Kirby that if he helped out Marvel that Goodman would reward Kirby. Joe gives the impression that Kirby stabbed him in the back, but there is no record of Kirby signing anything, or giving a deposition of any kind where Kirby undermines anything claimed by Simon. In fact, there is no record of Kirby doing anything on this case. Amazingly, a simple phone call would have ended any dispute. The case was resolved when Marvel and Simon came to an out of court agreement where Joe would receive an undisclosed sum of money if Simon would end his claim and agree that his work at Timely was “for hire”. Kirby might have received some sort of payment for a promise never to join in a future claim for copyrights on Captain America.

On Broadway in 1967, a small play appeared, written by Bruce Jay Friedman—a writer who worked for Martin Goodman a long time—mostly in his sweat magazine division. The play is called Scuba Duba a witty examination of racial tension and obsession. The titular character was played by Cleavon Little, later renowned for his work with Mel Brooks. This play received rave reviews, and featured quite possibly the first nude scene. Mr. Friedman also wrote the play Steambath and has a long connection to Broadway. The play did not last long, but long enough for Life Magazine to do a write-up and review which featured a photo that by itself meant nothing, but 4 years later would be reinterpreted by Jack Kirby into a continuing character in his most personal work. It showed Cleavon Little as an obsessed scuba attired black guy bounding in his ridiculous flippers with a large mask perched on his head.

Brian Epstein died in Aug. 1967. Unknown to most, this new need to run their own business tore the Beatles apart; unofficially, Paul became the guiding hand behind the Beatles. He organized studio times, and album creating. John went along for the ride, but he says that the times at the studio were no longer group happenings, but rather members of the band playing back-up to individual members’ songs. Togetherness was a thing of the past. In the name of the Beatles, the members were really four solo acts pressed into one album. John was the first to publish a solo product, with the usually diffident Ringo Starr following suit. Paul and his new wife, Linda bought a small four channel recorder and started doodling and creating a private collection of songs. Yet despite trying to stay together, members started moving in and out as egos took over. George left one recording in a huff, and there was actually talk of Eric Clapton being called in to replace him.

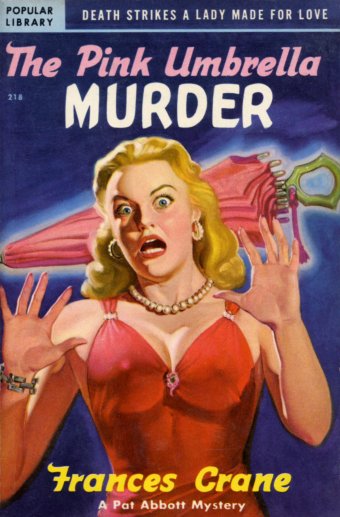

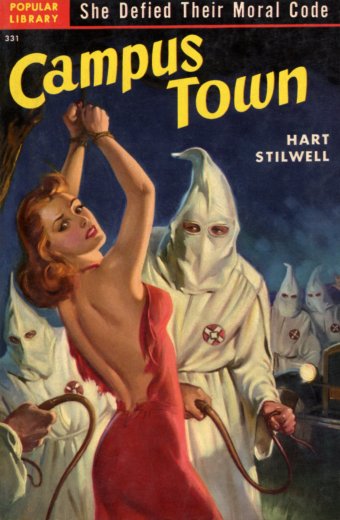

Ned Pines had created comic books in the Golden Age. His line became known by the unwieldy name of Standard/Better/Nedor. He had gotten into the burgeoning paperback industry when he opened Popular Library paperbacks. These were some of the schlockiest titles going; pulp magazines without interior spot illustrations.

They loved them some headlights and racy blurbs

In early 1968, Perfect Film and Chemical Corp. bought them outright. Perfect Film was a securities corporation known for buying troubled companies and selling them for quick profits. Perfect Film was talked into lending Curtis Publishing Corp. 5 million dollars.