Previous – 10. The Girls Take Over | Contents | Next – 12. Ghosts In The Attic

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

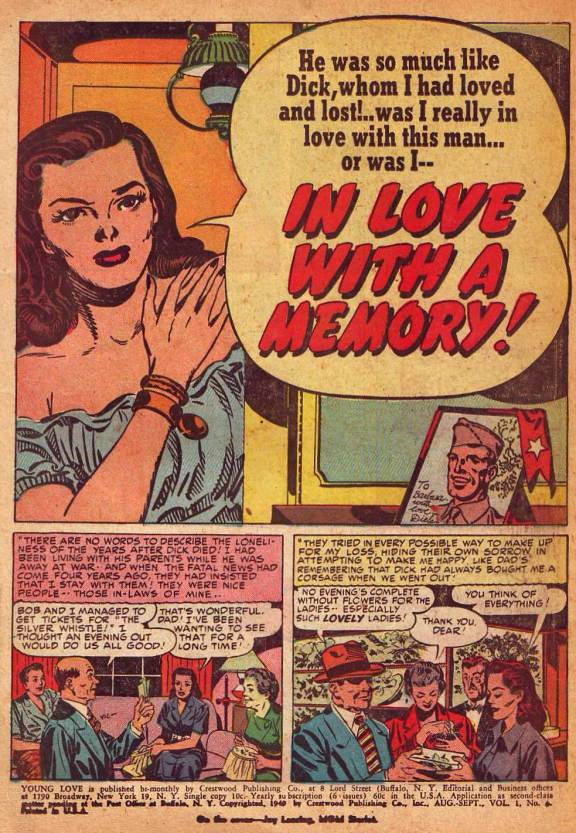

TALES FROM THE HEART

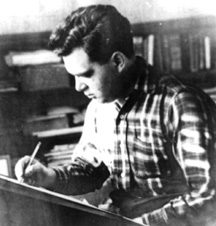

When Joe took his proposal over to Jack Kirby he knew there might be problems. Could Michelangelo paint a mural with stick figures? Could Mozart compose an advertising jingle? Could the pre-eminent action and adventure comic artist make the transition to a quieter mode of story-telling? Could Jack draw a convincing story with one hand tied behind his back–the hand holding all the power?

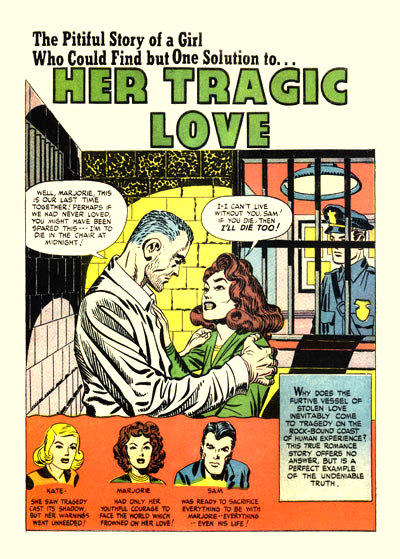

The romance genre presented a thorny problem. Since these stories dealt with average people and their real life crisis, the solutions had to be realistic. A broken heart wasn’t solved with a blow to the head or a flying shield. Simon and Kirby had no experience with realistic fiction. Prior to the romance books, a typical S&K adventure featured a quick action packed introduction, a brief action packed mid-section where the hero is seemingly trapped and doomed and a fast action packed finale wherein the hero escapes and saves a hapless female, or the country, or even the world. The thread running through everything was non stop action. Don’t let up and allow the kiddies to realize the absurdity of it all. The idea of characterization and humanity and depth rarely arose in the earlier books. At times there were hints of romance such as in Blue Bolt and the Green Sorceress, but it was never developed and nurtured. No back stories fleshing out the characters motivations. We knew little more about Captain America the person after the tenth issue as we did after the first chapter of issue #1. The civilian identities of the Sandman, Manhunter, Guardian, or even Rip Carter never really came into focus; they never evolved, changed, or grew as humans. They were interchangeable archetypes who exist merely to keep the action moving forward. We never learned anything about the early years of the Newsboy Legion or the Boy Commandos. Did they have parents or siblings? Why are they there? What are their dreams? As examples of episodic action tales, these stories were without peer. Kirby’s dynamic artwork and the bare bones plot propelled the action along at break neck speed. But as literature, or even compelling drama, they were sorely lacking.

When romance comics first hit, Joe felt Jack’s style might be a problem. He didn’t want the girls to look muscular and brawny. He first sought out Bill Draut and Mort Meskin, artists whose natural style was more slick and graceful. But when Jack was finished the first script, Joe immediately changed his mind; Kirby had completely rewritten and reinterpreted the script making it more real and better characterized than originally planned.

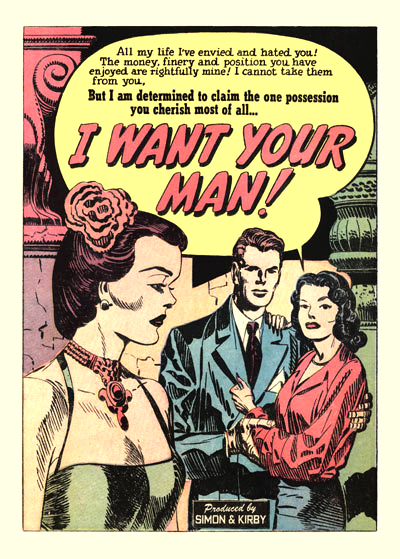

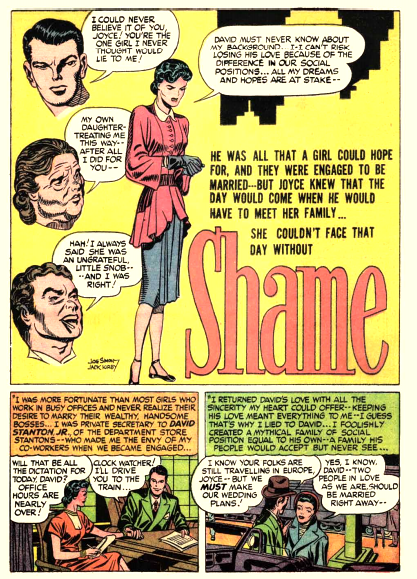

If the reader was to be drawn into the romance tales the writer and artist had to capture them with riveting plots and solid true-to-life characters acting in a realistic, yet dramatic fashion. There would be no instantly recognizable hero or a recurring villain to draw upon month after month. Each issue had to attract the reader on its own merits. With the romance books, the reader had to be brought back with the promise of new and different stories that would pique their interest, pull at their pathos, and stoke their fantasies of a world more daring and sensational than their own moribund reality. The tales were ripped from the headlines; racial intolerance, class warfare, even juvenile delinquency were presented as part of their human dramas.

Defiant but chastised

The need for better plotlines, and more literate scripts forced Jack and Joe to use muscles never used. The emotions of desire, rejection, jealousy, fantasy, and shame had rarely if ever been used in their action tales, and in the absence of the flying bodies, fist fights and explosions so vital to the adventure strips, they had to learn to excite the readers through words, facial expressions, and subtle gestures. The stories had to become even more cinematic, they would have to perfect a different attitude to pacing- the slow build up of passions and release. They had to set scenes by use of atmospherics, lighting and staging, changing moods with close-ups, and panoramic vistas. All of these were present in the action tales, but the timing and direction needed for romantic tales was totally different. They learned the value of subtlety and pathos, the need for punishment and redemption, and that in real life, no one is all good or all bad. They embraced humanity in all its messiness and glory. Their earlier simpler characters had to become flesh and blood. Simon and Kirby became dramatists.

Jack Oleck, Joe Simon’s brother-in-law became the mainstay of the writing corp, filled out with Ed Herron, Carl Wessler, Otto Binder, and others like Kim Aamodt and Walter Geier. In a revelatory interview by Jim Amash, Kim and Walter talk about the inner workings of the S&K studio.

Aamodt: Well Simon and Kirby wrote the plots. They sat there and wrote them, and that’s what we followed.

Aamodt: Jack did more of the plotting than Joe. Jack’s face looked so energized when he was plotting that it seemed as if sparks were flying off him.

Aamodt: I remember Jack Kirby was very good at making up titles. I remember giving him a lame title, and Jack said,” No we’re going to call it ‘Under the Knife.’ ” It was a surgical story. I was impressed that Jack came up with titles so quickly.

Aamodt: I really sweated out plots, unlike Jack Kirby. Jack just ignited and came out with ideas, and Joe’d just kind of nod his head in agreement.

Aamodt: Joe was on the ground, and Jack was on cloud nine. Jack was more of the artist type; he had great instincts.

Geier: Every time I went up there I saw both of them (Simon and Kirby). And they always gave the writers the plots. Jack Kirby was great about that; he always came up with the plots. Jack had a fertile mind.

Geier: Joe used to sit there when the writers came in for conferences. They sat there and made up the plots for the writers. Jack did most of that. Joe would say something once in a while, but Jack was the idea man.

Geier: Joe didn’t talk much. He could come up with decent plots, but it was usually very sketchy stuff. A lot of times Joe would say, “Awww…you figure out the ending.” Jack would give me the ending, because he was good at figuring out stories. It was not hard to work with Jack.

Geier: They were Jack’s plots. I just supplied the dialogue.

Simon notes: “All stories were shamelessly billed as true confessions by young women and girls, when in actuality, all were authored by men. In the years of producing love comics, we were unable to come up with one female script writer who could satisfy our requirements for dramatic love confessions in comic book script form.”

For Kirby this must have been excruciating, for this was a guy who had perfected the art of balletic pandemonium; bodies in constant motion taking up not just a panel, but at times whole pages! Jack was a scrapper, a fighter, a man of action, and his art mirrored this. To ask him to limit the scenes to quiet head shots, slight gestures and gazing eyes was akin to hacking off his arms. It took away his reason for being! Kirby meant power! Kirby meant action! But Kirby also meant making a living and doing what was needed to tell a story and sell a book.

Can you recognize the inking traits?

How could he be true to his artistic nature and still sell comics to girls? New problems called for new solutions: Jack created a new sub-genre. The romantic adventure thriller! He would tell his tales of pride, and lust, and redemption, but he would structure them in action settings full of passionate people in dramatic moments set in exotic locales, leavened with humor and caring. While other artists would settle for the talking head route, Kirby found that unthinkable. His characters would always be in motion, even when talking there was action. The rare times when they were standing still, they would still be active; eating, drinking, smoking anything but hands at their sides. It was the hands, always the hands! Kirby’s tales were full of gangfights, sporting displays, and war torn locales; active bodies on display in dramatic situations. You could envision Humphrey Bogart, or Spencer Tracy wooing Kate Hepburn or Vivien Leigh in Tangiers or Tibet. The cinematic influence was once again Kirby’s model for story-telling.

Another difference was the serious nature of these tales; no more the slapstick approach. With passions ripped right out of the headlines, they wrote of class warfare, prejudice, peer pressure, and the duality of human nature. Though they had to take the “for the more adult reader” blurb off the cover, they never talked down to the readers, the stories were adult fare. Overt sexuality was never displayed, but it certainly was hinted at. These weren’t Betty and Veronica teenage cartoon gags, these were real, the people were real, the crises were real, and the feelings were real. The readers could recognize their own situations, fears and dreams in these tales.

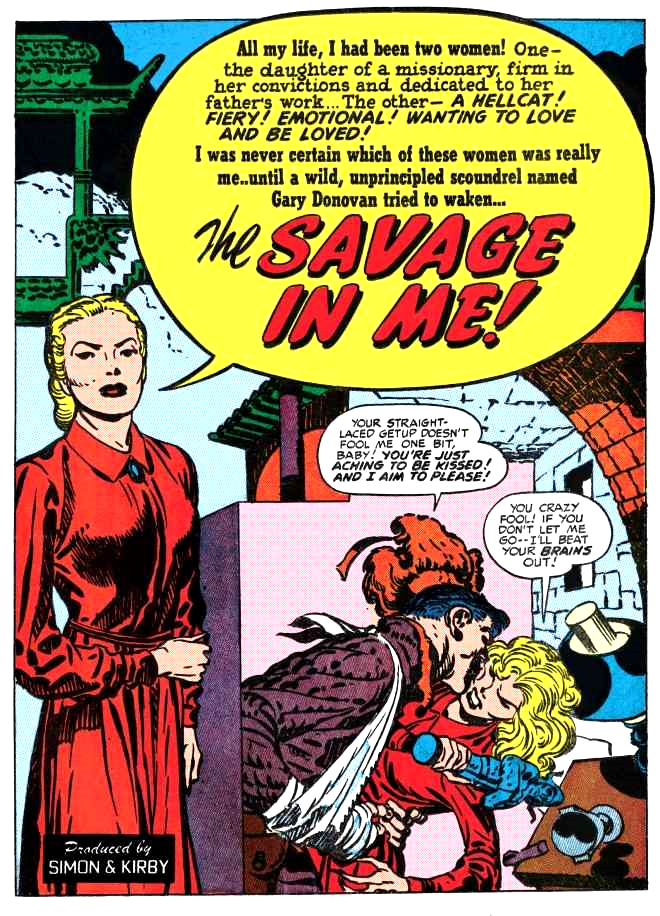

One of the classics of this sub-genre is The Savage In Me from Young Romance #22 Jun 1950. The story takes place in post-war China and centers on Augusta Hatcher. The splash page is a classic Joe Simon lay-out; the prim, elegant Augusta Hatcher standing along the left side confessing her problems. The lettering is among Howard Ferguson’s best. Using five different fonts in the confession’ each emphasizing a different thought, he built to a large bold font, proclaiming the title. In the lower right corner is an inset of a furious fight. The lack of details adds to the suspense, though we do know it’s not a friendly scuffle. The splash page is an excellent example of the two sides of Kirby working together. First we see Miss Hatcher in a confessional introduction, telling us she has always been two women: one, the obedient prim and proper daughter of a missionary; the other, a passionate hellcat wanting to be unleashed. Yet she is never certain which was the real Augusta Hatcher until a wild scoundrel named Gary Donovan tried to awaken…The Savage in Me! The beautiful, but school-marmish appearance of Miss Hatcher seems to be beckoning to a smaller inset panel where we see a man roughly forcing his intentions upon her. She is fighting back, furniture flying, her hair awry, and face clenched in fury. So on one page we get the new Simon/Kirby dramatically introducing us to the dual personality of Augusta by dramatic text, and cinematic juxtapositioning of the two natures of Augusta, while the old Kirby captivates us with the vitality and dramatic action of the art.

Pages two and three also demonstrate the different modes of storytelling by Jack, which ingeniously highlight the two personalities of the main character. Page two is a quiet page where we see the prim figure of Augusta patiently teaching her charges. The first five panels are small, quiet gestures and easy conversation with a most inquisitive boy inquiring about the “dragon” she possesses inside her—not knowing it is an allusion to her latent passion. In the last panel, the mood quickly changes as she is abruptly grabbed from behind and a man roughly kisses her, much to the amazement of the kid. On page three the first five panels present a classic Kirby battle. Augusta fights off her attacker like a wild woman, kicking and screaming for all she’s worth. Until panel six, where the action ends and the attacker walks away with a jaunty shrug. Just going by the pictures one could get the impression that the man was trying to rape her, but being a comic magazine the text assures us that he merely wanted to kiss her. On these two pages Kirby shrewdly shows again her two opposing sides, the quiet dignified lady and the she wolf protecting her virtue. Visually, Augusta is shown in a high buttoned dress with long sleeves, her hair in a tight bun. No skin would ever be displayed from this straight laced lady. Kirby also uses the panel layouts as a means of leading the reader from page to page by making the final panel as a change of pace and a change of direction pushing the reader to the next page; a very clever story telling technique.

Page four is pure cinema. Augusta is shown sitting in front of a dressing table looking in the mirror. The two faces are seen in direct opposition and she is fighting with herself about the attack and what she was feeling inside. She is clearly upset, but her reflection is taunting her for secretly wanting it to happen. This is very powerful stuff; this is a Kirby we haven’t seen before. Using only facial expressions he has created tension producing more emotion, passion and energy in these four panels than in the five panel fight scene that preceded it. Kirby has given this character more depth, passion, pathos and humanity than in all his super-hero stories combined. Kirby had used the mirror reflection gimmick many times before, but never so intimately or psychologically engrossing. The page ends with Augusta arriving for dinner and surprisingly being introduced to the man who had attacked her just a short time ago. She is defiantly in her haughty composed persona and true to form, he is unrepentant and ungentlemanly.

The next page introduces us to Gary Donovan. He is supremely confident and brash, and fond of talking about himself. He is used to getting his way. This is not a typical Kirby hero; they tend to be stoic and humble. Donovan makes his brash intentions towards Augusta known, much to her disgust. Donovan explains that he has been injured fighting with a warlord named Yang-Hu who will soon reach the town and ransack it. Donovan suggests that the missionary and his daughter leave for safety. The missionary tells him that warlords come and go and he can handle them. Augusta tells her father that Donovan sound like a scoundrel and will probably hang for his insolence.

The next few days, while Donovan is on the mend he entertains the kids, slowly melting Augusta’s hard heart. He ultimately confronts her and forces her to admit her passion for him. Just as they fight over their future, Yang’s men appear in the distance. The father and daughter are determined to stay, but Donovan has other ideas and knocks out the father and bodily forces Augusta to hide out in his boat. Donovan had worked out a deal with a local smuggler to get them safely through the lines. While Donovan is apologizing to Augusta for the rough way he handled her and her father we see the town going up in flames, justifying Donovan’s actions. Then Donovan explains that his actions were not just to save her life, but to keep them together. He tells her “Besides we want each other, hang it! All the principles in the world can’t condemn that! It’s a law of nature—born before any other ideas came into being. Now listen to me carefully Augusta! There’s a real woman inside you! A woman who will cast aside all else to answer her instincts.” Finally she has reached the point where she must decide which side of her personality she wants to control her. While she is lost in thought, her father approaches, she explains to him the quandary she finds herself. Her father listens, and then offers her advice. “Then be true to the woman you are—the woman who loves Donovan!” The story ends when we see Augusta sneaking up behind Donovan and throws her arms around him, he turns around is astonished to see her with her hair down in loose curls and she is wrapped in a body hugging cleavage baring sarong. He laughs at the change, and tells her that he is not a river pilot, or smuggler, but an agent of a large textile exporter and that her future is secured and safe, but he will never lose his enthusiasm for his wild woman. The bad boy became a good boy, and the good girl became a freak.

This can’t end well eyebrows too big

A nicely told story, somewhat chauvinistic, but both characters are not whom they seem, but by the end, they are who each other wanted. A very mature theme, well presented in a dramatic cinematic format light years ahead of what Jack was doing two years earlier. There was action, but in a realistic fashion, and there was tension and climax in a satisfying fashion. There are small bits of continuity problems such as Augusta’s red dress switching from long sleeves to short sleeves from panel to panel. But the passion and sexual tension was real and evident. The anguish of her search for self was so strong and her frustration so plain in her Kirby drawn face. Donovan’s smugness was so obvious even without reams of text explaining his personality. This part of storytelling became so strong for Kirby that when he later reverted back to super-heroes with flaws, his characterization skills helped the stories come alive.

Gil Kane once said, “You don’t realize the underlying strength of their storytelling until you see them working that kind of material, anyone can make a page interesting when they’re blowing up planets or having a monster devour a city. Joe and Jack made it interesting when two people were just standing there having a quarrel, or professing their love. They employed the same mastery of character in all their work but in the romance books, it was stripped down to the essentials and you saw how well they could make their people breathe. Later, when they brought in the planets blowing up, it was so much more effective”

Once again Richard Howell;

“Simon and Kirby’s approach their romance comics with the same attitude they brought to superhero, adventure, humor and crime comics: Make them exciting! S&K’s electric compositions, active posing, and raw expressive inking were at a high point. Those qualities, coupled with the team’s command of comics storytelling and the touching and incisive stories they had to tell, enabled them to create some of the most dramatic, affecting comics stories ever produced”.

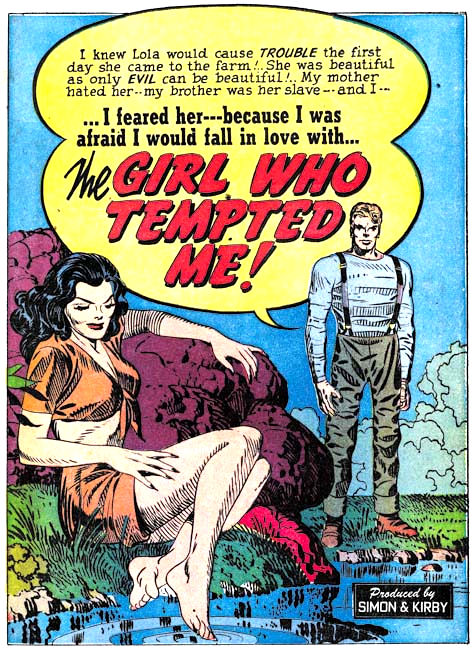

The artwork followed on the nourish stylings of the crime books with much crosshatching and deep shadow work. The swirling snaking shadows danced through the pages. The geometrics at times overwhelmed the performers in these passion plays. Kirby played the physiques straight, no outlandish perspectives, or post-steroidal hulks to be seen, just healthy normal men and beautiful, sexy women. The faces took on an increased variety and the facial expressions became startlingly eloquent. Kirby’s women had always been on the lean wiry side, but now they would run the gamut from Hepburn haughty, to the vampishness of Rita Heyworth or Veronica Lake. View the splashpage to “Was Love to be my Sacrifice” (YR #9) or “The Girl Who Tempted Me” (YR #17) and then claim that Kirby couldn’t draw sexy, beautiful and varied females.

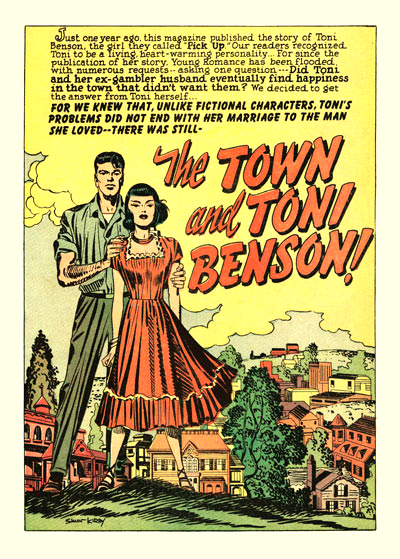

WOW!!! No costumes, masks, or cowls, just real people 3 fonts one blurb building in intensity

Joe Simon’s layouts for the covers and splash pages were works of genius; usually laid out with the sexy female “confessor” introducing the readers to the premise and warning them to avoid her mistakes and fly right. This aspect engaged the reader with its immediacy and drama. This formatting evolved from Joe’s earlier dramatic layouts on the pulp magazines. Ferguson’s multi font word balloons were the perfect enhancement to the splash giving it a weight and artistic flourish the equal of only Will Eisner.

The Simon and Kirby sheen was at its highest peak.

Over on the crime titles they soon ran out of true stories and they changed from historical factual reenactment to fictional stories using the same confessional style of the romance books. “The Last Bloody Days of Babyface Nelson” gave way to “I was a Come–On Girl for Broken Bones Inc.” using the same first person don’t do as I did template as the romances. Once again, the boys had more work than they could handle. Work at Hillman had ended, but at Prize/Crestwood they had three full bi-monthly comics to produce, plus they were editing some of Prize Comics other titles, like Prize Comic Western, and Charlie Chan. Joe’s small studio needed to expand. In an interview for the Jack Kirby Collector artist Carmine Infantino remembers being asked by Joe to work on Charlie Chan

Kirby cover template used many times – Signed Infantino definitely Kirby

TJKC: When you started working in the business, did you cross paths with them very often?

CARMINE: …. They worked for Hillman, and so did I. That’s when we met. Then they went to Crestwood and they invited me over to Crestwood to do Charlie Chan for them and I went over there.

TJKC: Did you do Charlie Chan directly for them?

CARMINE: Yep, for them directly.

TJKC: So how did that work? Did you ask for the assignment or did they call you?

CARMINE: No, no, Joe called me and he said-and he knows I’m working with DC-“Will you come over here and do Charlie Chan?” I said, “I make a lot more money than you can pay for this thing,” but then I thought about it. I could be there working with Kirby and Mort Meskin. I thought it’d be worth it. I worked for less money and I worked for him for about a year. It was a great learning curve.

TJKC: Did you work in the studio?

CARMINE: In the studio and I would go home and do DC’s work at night. After a year, I was collapsing, I couldn’t continue.

TJKC: What was it like working in the studio with them?

CARMINE: Oh, Jack taught me-tremendous. He was unbelievable.

TJKC: When he worked, did he ever make conversation?

CARMINE: He’d make conversation. You’d ask him a question and he’d answer you. One time I did a story-it was about these two guys beating up an old lady-and I was drawing it and I was having trouble with it. I said, “Jack, what do I do to get this thing right?” and he says, “Don’t show them hitting her. Have one villain on the couch smiling and watching the shadow of the other villain hitting the old lady. That’ll work in the reader’s mind more than seeing the actual action,” and he was right; little things like that he taught me.

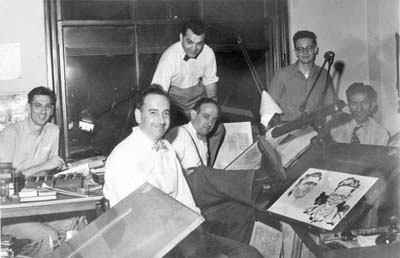

The Simon and Kirby team of the 1950s Joe Genalo, Joe Simon Jack Kirby (standing) Mort Meskin, Jimmy Infantino, letterer Ben Oda

Another couple of legendary artists who made their comic book debut in a Simon/Kirby produced book were John Severin and his partner Will Elder. In issue #32 (Oct. 1948) of Headline Comics John and Will began doing back-up strips and soon began helping out on the romance and western books. With issue #72 (Nov 1948) of Prize Comics Western John and Will began a steady job on several strips. Jack would provide a couple nice covers for this series. John recalls the early meeting in an interview in JKC #25.

“We- Bill Elder and I were partners at the time- were lucky enough to be given a script for one of the crime comics. The story was about two children- a young girl and her brother who murdered their mean stepfather.

Soon we were doing westerns for Crestwood sister series Prize Western. “The Black Bull and The Lazo Kid were two of the series we did before the editor Nevin Fiddler spoke to me about a new character they were creating called American Eagle. I agreed to take it on and that ended our work with Simon and Kirby They had been very helpful with their constructive criticism to two novices in their business.”

Quite a team – Elder and Severin – gritty realism

Elder remembers as well:

ELDER: Yeah. And then Johnny Severin came around and got jobs for the two of us. Severin could draw very well. He had a good memory for mechanical things. And I could ink really well. I could ink fast; he drew fast. We were both the opposites of each other. I couldn’t draw as fast as him. To make money in that business, you have to be pretty fast and turn out a lot of material. We turned out the best we could at that stage of the game. We hit it off with the few samples that we showed Simon and Kirby.

GROTH: How did you get hooked up with Joe Simon’s shop?

ELDER: Through Kirby, because Kirby was the artist and Simon was the businessman.

GROTH: How did you know Kirby?

ELDER: Well, through some of the artists. We came up to his office and we saw some of the work that was being done, and I said, “We can do it.” John Severin was the same way.

GROTH: Well, how did you discover the Simon/Kirby shop?

ELDER: It’s hard to put my finger on. I can’t know exactly when that happened.

GROTH: And you went up to Simon’s shop, and he gave you some work…

ELDER: He gave us some work. It worked out pretty well. We weren’t getting paid very much, but that was the reason we got the work. “There was a guy in the office who was very funny. I wonder if you know who I’m talking about if I mention what happened. This guy would follow us down the stairs, get out in the middle of the street and start directing traffic. Severin and I looked at each other: See any cops around? I look at this guy, directing traffic. I think he had a nervous breakdown; I found out later. Couldn’t stand the traffic. I couldn’t blame him for that. But to direct it?”

GROTH: I see. How much work were you doing for Simon and Kirby?

ELDER: Not much. I’d say about maybe a half a year’s worth.

One day, an inker named Jack Abel saw something that amazed him. He quietly watched Jack pencil a figure. “When most artists start to draw a figure, they do little ovals for the head, and action lines for the legs, arms, etc. Well he simply started at the feet and just continued on up with one continuous line. And the figure was perfectly drawn, doing what it was supposed to do in the panel. When he finished, he turned to me and said, “How do you like that kid?” “I was flabbergasted, I never knew it was even possible for a guy to do a well drawn figure without making little sketchy guide lines.”

As good as Jack was, George Roussos says that Joe Simon continually beefed up Jack’s confidence. “Get on drawing Jack. How many times do I have to tell you not to use the eraser. And then Joe would take it away. With that kind of encouragement, you grow muscles; and Jack grew and grew because he had no restraints of any kind. “Joe, being a bright guy, foresaw the giant in this man and encouraged him. No one in the business ever did that.“

The boys may have been busy, but romance wasn’t lost on them. Joe and Harriet brought forth Jon- their first born, soon to be followed on May 25, 1948 when the Kirby’s welcomed Neal into the family. Jack had a son!!!

With growing families came the need to expand. Harriet hated the city and on weekends the group would pile into Joe’s car and head to the suburbs to find new digs. With Levittown style developments sprouting up like weeds, they soon found a new development in Mineola, Long Island.

Class warfare was never far – the tragedy of wartime romances

Mineola was one of the many small rural villages that stretched across Long Island. Its main claim to fame was nearby Roosevelt Air Field, where the young Charles Lindberg began his trans-Atlantic flight in 1927. Post WW2 with the Long Island Railroad making it a convenient trip into New York City, the town more than quadrupled in size as the suburban explosion transformed Long Island. A comfortable 35 minute ride would find the traveler at the hub of New York’s Penn Station, just a few minutes walk to the center of the publishing district.

With GI Bill loans secured, the families moved into adjacent houses and set up studios in their attics. The move was not entirely positive.

Joe explains; “When we arrived, there was something different about the place. It seemed ugly and barren. Harriet was fuming. ”We’ve got rocks for a lawn!” The developer had stripped the topsoil from the entire development and sold it to finance his construction. “Maybe he’s gonna give us new dirt,” Kirby, the city boy commented. We all looked at him. “Well, the damn stuff was old,” Kirby persisted. Roz shook her head perplexed. We stormed into the builders home a few blocks away, screaming mild obscenities. The crook didn’t even have an office. I never sold you topsoil,” he blustered. “If you must have topsoil, I’ll sell you some.” Much as we tried, we couldn’t get satisfaction. “It’s like dealing with a goddam comic book publisher,” Kirby lamented.

The families were close, but because of the boys’ nighttime schedules, they never socialized much. As Roz put it;

“We were good neighbors, and I socialized more with Joe’s wife Harriet because the kids were all the same age. We’d go to the beach a lot. There was another couple… we’d all pile into the cars and go to the beach We were all so busy, the boys were working at night and we were busy with the kids. We didn’t really socialize that much, but we socialized as neighbors, took walks with the children, took them for ice cream and things like that. I wouldn’t say they (Jack and Joe) were close, but they got along very well. Jack always thought of Joe as a big brother.” Roz’s only complaint was that Jack and Joe’s constant cigars turned everything a horrible yellow shade.

Living this far from the city presented a new problem. Joe would jokingly tell of Kirby’s driving acumen; “Jack had a problem with road rage. When we were living out on Long Island, if he was driving and a little old lady cut in front of him, he’d get so angry that he’d want to ram her car from behind. He used to get into one accident after another, and finally Roz took his car away from him.

With the Aug 1949 issue of Detective Comics (#150) Jack’s work on Boy Commandos ended; casualty of a war comic without a war. But not before Jack once again dipped into his iconic bag of stories. In Designer of Doom (Boy Commandos #32, 3/49) the villain is once again a painter who paints the deadly future of his victims. A theme used over and over. The attempts to transform the group from soldiers to civilian adventurers never really clicked, though Kirby gave it a damn good try. It had been a wonderful and successful run for DC and for S&K. It would be a decade before Jack returned to DC.

Movies take from S&K

At the same time as Boy Commando’s cancellation, there was another shakeout at DC. Mort Meskin, who had been a mainstay at DC since 1942, lost his job on several long running assignments. It’s been said that he was no longer reliable, and suffered from periods of depression. There is some speculation that Mort was undergoing treatment from cult figure—Dr. Wilhelm Reich. Mort guaranteed the end of his tenure when he jumped up on a desk, wielding a T-square like a sword, challenging the editors. But Mort was one of the acknowledged masters of the form. Joe and Jack had known Mort for quite a while. Mort was a peer. Born a year before Jack in Brooklyn, it was destined that their paths would cross. He had been at Eisner/Iger the same time as Jack. He was most known for originating Sheena, Queen of the Jungle for E&I. Mort was at DC when Jack was working at the offices loading up on inventory pre-draft. Mort also had a regular patriotic strip at Prize, named Know Your America; where he and Jerry probably had contact with Joe Simon. With his partner Jerry Robinson, Mort had done a strip at Fiction House, plus a few small freelance romance jobs previously for S&K. Mort had become famous for concise, terse well-rendered stories. Steve Ditko once said about Mort; “There is a vast difference between a comic artist who tells a story and a comic “technician” who draws detailed items or objects.” This difference rears its head quite often in the history of comics as new “hot” artists—often sensational detail men—soon give way back to the real storytellers. (see Neal Adams).

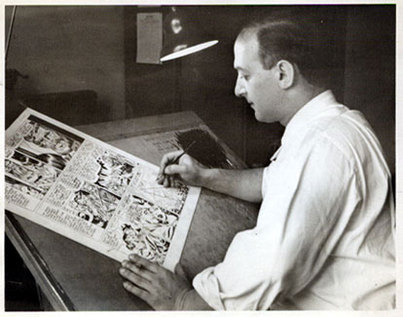

The yin to Kirby’s yang Morton Meskin

With Mort accepting the job, S&K now had 2 top tier talents on the roster, a one-two punch the envy of the industry. The pairing got off to a rocky start when Mort went into an artistic block period and was unable to draw. Joe explains; “Since I had been a long time fan of Mort’s, I urged him to try one of our scripts. It was a story for Black Magic, the comic advertised as “The Strangest Stories Ever Told”….Mort took the script home and didn’t show up for weeks. When he did return, he shoved the script at me. It was rumpled and soiled. There was not a single drawing….”I can’t do it” he sighed. “There’s no way I can get started”…. An idea struck home. “Why don’t you work here Mort in the office with us”. Mort agreed. We gave him a drawing table and a fresh script. He examined it for hours. All of us pretended not to notice his work-or lack of it. “I can’t,” he said I can’t face a blank page, I panic”. I walked over to his desk and penciled in some lines and circles on the board. “There. It’s not blank now”. Mort sat down, glanced at the script, and then drew around the lines and circles, continuing with the most expert penciled drawings until the page was complete. From that day on, every morning, I or one of the other artists would draw meaningless lines and circles on his blank page and Mort would draw without further problems all day. He was probably the fastest, most inspired artist in the room, and certainly one of the most dependable.” Mort was a mainstay until the studio disbanded. Also coming over from DC was inker extraordinaire George “Inky” Roussos.

George was born in Washington D.C. but moved to New York when orphaned. Self taught as an inker he ended up at DC inking over Jerry Robinson and others such as Mort Meskin on the Vigilante. He also helped out Jack Lehti on that new comic Picture News. Always busy, George came over to S&K with Mort Meskin to fill in his workload. George Roussos recalls the studio in an interview for the Jack Kirby Collector;

“In fact I worked in the office sometimes. They were up somewhere off Broadway. It was not bad, a small outfit, a lot of fun. Ben Oda, the letterer was there. Carmine Infantino’s younger brother (Jimmy) worked there for a while; very nice guy. Marv Stein, Mort Meskin were there. I was working there on a freelance basis. I liked working with Joe and Jack. Joe was the real business manager; a very clever, efficient guy, and also an excellent artist. He was the brains.”

“Jack was there at the drawing board. He hardly talked; he just produced. So there was a lot of energy inside of him and he didn’t waste on talking and kidding around. He’d do six or seven pages, starting from the left side and go right across, the next line and the next line….(laughter) amazing guy, really. It was a pleasant atmosphere and I enjoyed working there.”

The versatile George Roussos – Marvin Stein

The next long time member to join up was Marvin Stein; he came over from Quality and Croydon and immediately picked up work in Black Magic, and the romance books. Marvin would become a top producer and work for S&K and then Prize for many years. Jack considered him one of the best. He also inked a lot of Jack’s romance stories at Prize.

In 1949; the Kirby’s once again picked up stakes and moved; this time just a short distance to the next town. Neal, though young remembers most of the details; “Buying a house in East Williston, Nassau County, it was to be our home for the next 20 years.

The decade of the 40’s ended with Jack in a secure and stable work situation, just the opposite of how it started; with great periods of doubt ending in victory, while moments of great promise ended in disaster. Jack had been through crazy publishers, war, stretches of unemployment and pre and post war bust and boom, but he was now doing the best work of his life, and his family life was never better, he was at a high plateau and enjoying the view. With a now four ongoing titles they were on a roll. Bring on the Fifties!!!

Previous – 10. The Girls Take Over | top | Next – 12. Ghosts In The Attic