Previous – 8. Call To Duty | Contents | Next – 10. The Girls Take Over

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

PICKING UP THE PIECES

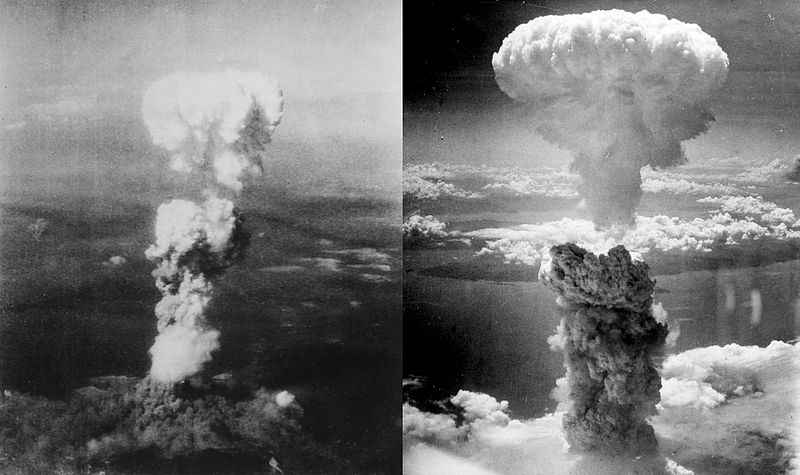

Jack’s war was over, and he was on his way home, but the world had some unfinished business. In July, at Potsdam, Truman, Stalin, and Churchill carved up the ravaged shell of Europe. With the signing of the Potsdam Pact, once again the world settled for temporary peace at the sacrifice of future turmoil. All efforts turned to Asia. On August 6 and 9, with a flash of light, and a burst of energy (see above photos) never imagined, except in the comic books, the Japanese Empire ended in a suddenness that shook the world. Life would never be the same.

Life back home was blissful. Roz pampered Jack and his legs were getting better by the day. Mama Rose’s cooking was putting back some of the weight he had lost. Best of all, Roz broke the news that she was expecting their first baby. Jack was ecstatic; “That’s the American way. Fight the war, come back, and start your family.” They continued living with Roz’s parents in Brooklyn with plans to get a new place once Joe returned and work was back in full production. Jack was receiving military disability, plus DC was still sending him small checks as they continued to use the pre-war inventory. It was mostly for covers, as the interior stories had run through months earlier.

Jack was determined to jump back into the saddle, and by September he had contacted DC about resuming work. DC welcomed him back gladly. While he and Joe were away, the strips had all continued with lesser artists. Oddly enough, his first new published work wasn’t for DC. As a favor for Jack Lehti, a friend from DC who had drawn the Crimson Avenger before going into the service, Jack provided a four page back-up story for a new comic book titled Picture News #1, (Lafayette Street Corp., Jan.1946.) The only aspect of this work worth mentioning was the lack of Simon-style inking is noticeable. At DC, Kirby was immediately returned to the Newsboy Legion strip and his first new Legion story appeared in Star Spangled Comics #53 cover dated Feb. 1946. That same month he also provided a Sandman story for Adventure Comics #102.

Jack soon returned to S&K’s best selling strip Boy Commandos, and quickly produced stories for World’s Finest, Detective Comics, and the self-titled Boy Commandos. With the end of the war, the Boy Commandos also came home, and Jack gave them a riotous welcome home. The boys return to New York, and Brooklyn wants the boys to see his hometown, so they sneak out to see his Brooklyn borough. No sooner do the boys arrive that they meet up with an old tormenter of Brooklyn’s, Big Nose Murgatroyd, (Is this a Jimmy Durante reference?) and his street gang. It seems that Big Nose has escalated from street punk to real hardcore burglary type. The typical Kirby gang fight ensues. The story ends with the Commandos bringing down the gang and helping Brooklyn’s old girl friend extricate her brother from Big Noses’ gang and sending him on the straight and narrow. Commandos, welcome to Kirby’s New York! You can take Kirby out of the streets, but you can’t take the streets out of Kirby. Jack also drew some filler strips for a new title, Real Fact issues #1&2 and later on #9. This was DC’s attempt at “good” comics.

Jack jumps back in

Kirby kept busy waiting for Joe to return, but not too busy to take a young eager beaver type under his wing. Martin Rosenthall was a high school student who would hang out at the DC studio. In an interview with historian Daniel Best, Martin recalled his relationship with Kirby.

“Kirby was my mentor. I saw him five days a week. When I was going to high school, DC Publishing was five blocks away. …” “Jack and I used to go out for coffee. I went to high school and the Cartoonist and Illustrators School at the same time, day and night. Jack was very kind to me. He was a cigar smoker, and one day for Christmas, I got him a box of cigars. It was the cheapest cigar in the world, but he graciously accepted it and he took me out to the Waldorf Astoria for dinner. I had my first shrimp cocktail over there. He was a very great, gracious man. He gave everything and shared everything with you. He was a wonderful, wonderful guy.” Martin would honor Mr. Kirby by making one of his earliest heroes Jim Kirby, a bright detective who took on a sinister scientist.

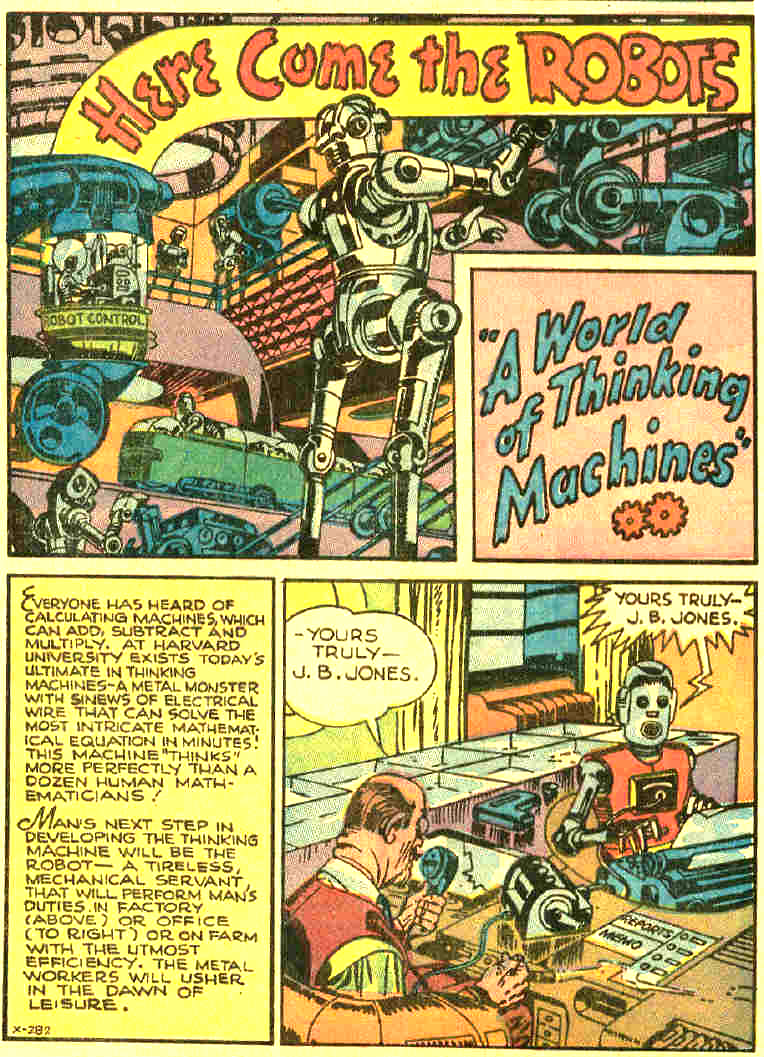

WOW! Thinking robots- whoda ever figure?

One day, Jack was taking the subway from his home in Brooklyn to the city. A tall, rangy young man spied him and his portfolio, came over to him and introduced himself as Frank. He said he had just started in the business and wondered if Jack had any advice. Jack and the man talked for awhile, Jack showed him his samples, which included a couple Captain America pages. The man was thrilled and took in every word Jack offered. Serendipitously, that man and Jack would meet again, under different circumstances.

Joe Simon was stationed in Washington D.C. After a year of patrolling the shores of Jersey, he had been reassigned to the Coast Guard Public Information Division, of the Combat Art Corps.

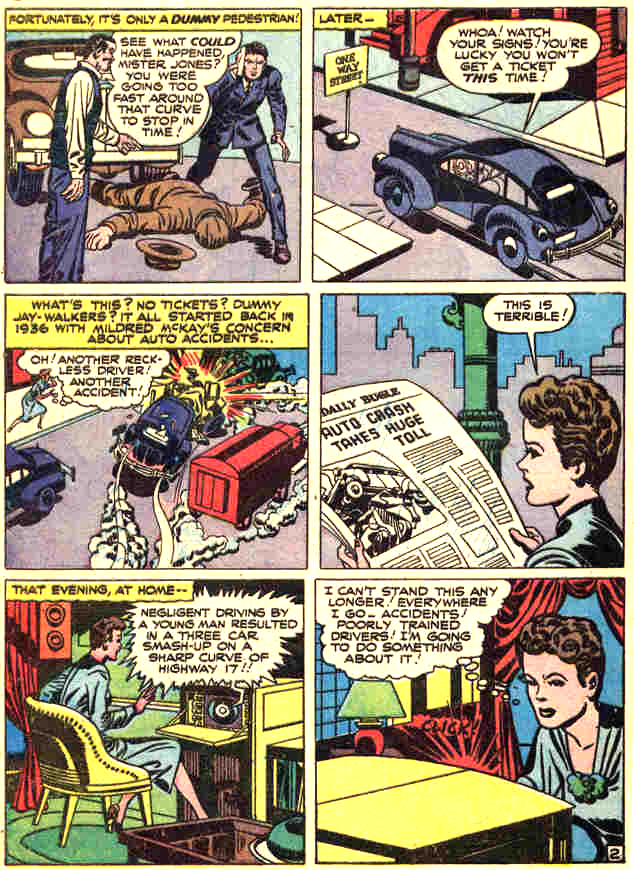

From Real Fact #2 solo Kirby, he even inked it Look what’s she’s reading, note – no hay.

The job was a public relations position whose goal was presenting the Coast Guard as heroically as possible. Joe would produce comic strips that spotlighted a member of the Coast Guard and the heroic deeds that he did. These would be syndicated and printed in Sunday newspaper comic sections titled True Comics. This led to a commission for a newsstand comic that was to be used as a recruitment tool for the Coast Guard Academy. Joe produced Adventure Is My Career. Street and Smith Publications was hired to publish and distribute. For this Joe received an official commendation and promotion.

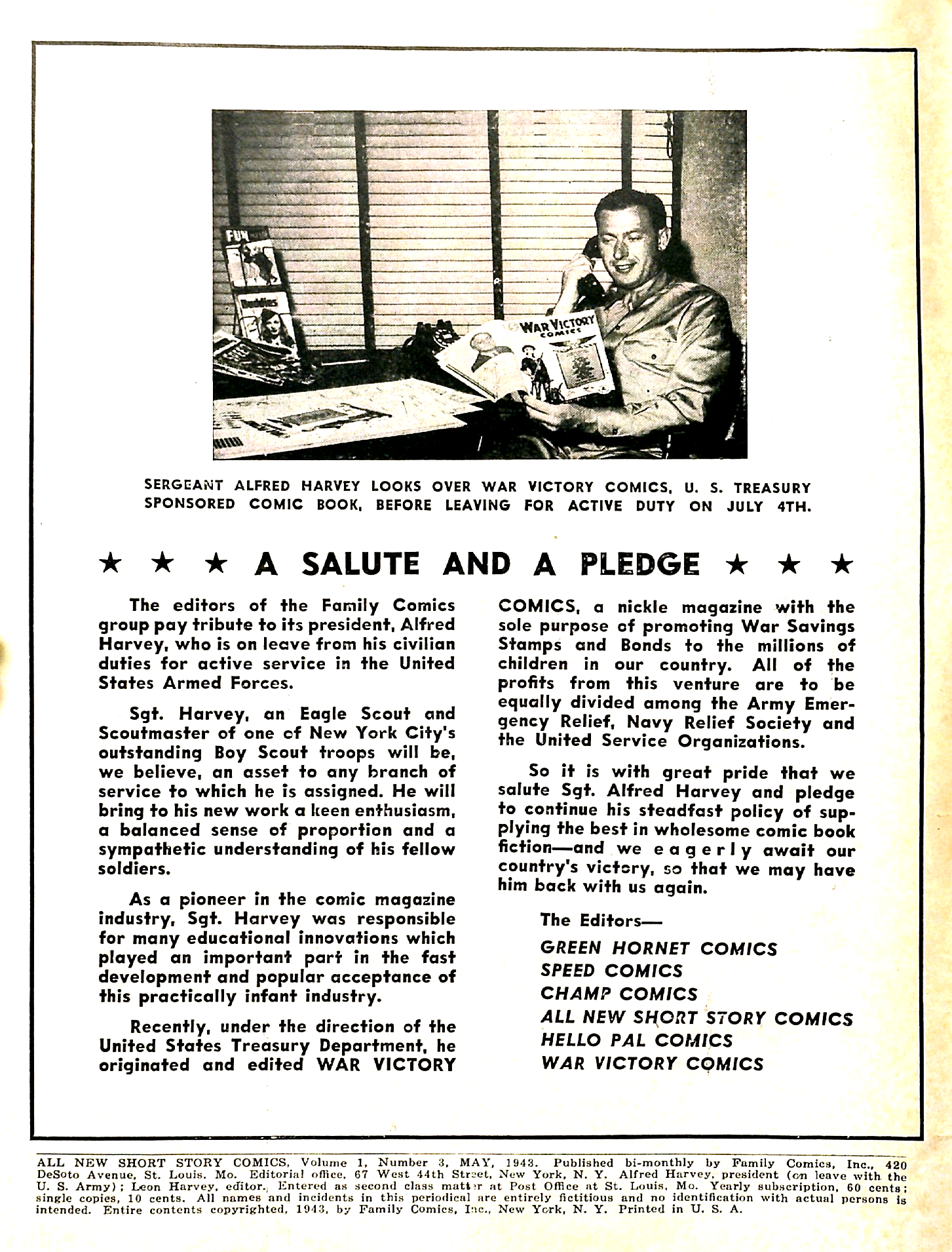

While in Washington, Joe had resumed contact with his friend Al Harvey. Al, now a Captain, was stationed at the Pentagon where he did similar PR duties for the Army. Yes there was a caste system where owners and editors had stateside safe jobs (see Stan Lee, Will Eisner, Al Harvey or Joe Simon) while the lowly artists found themselves on the front. Joe and Al had decided that when the war was over, Simon and Kirby would finally work at Harvey Publications. There they would have free rein over their creations, and as a further enticement, Simon and Kirby would receive a fifty/fifty profit split. This was unheard of at most publishers, but Harvey had been having success publishing licensed properties like Green Hornet. Part of the agreement was that S&K would also edit other titles for the line.

Al’s one of the good guys Harvey self-promoting

Soon after Jack returned home, he and Roz visited Joe. Joe and Al explained the new set-up and Kirby agreed- if Joe thought it was a good deal, who was Kirby to disagree- Joe always got them square deals. Yet Jack was already back at work for DC Comics. So they decided that Jack could continue at DC, as long as DC would allow it, while also working at Harvey–a decision that would prove helpful later on. Joe had also met some other artists while stationed in Washington, and asked them to join in this new venture.

Perhaps more important during one visit Joe met someone else who would become important in his life. From his bio, he retells;

“There was a secretary there who was the bookkeeper, as well. Her name was Harriet Feldman, and she was sorting mail or something. As I sat there, waiting for Al to be available, she looked over at me.”

“Would you lift your pants leg up?” she said.

“What?” I responded, wondering if she meant me.

“Lift up your pants,” she said.

So I lifted my pants leg.

“Go up to the knee,” she instructed.

So I did. Those pants had wide legs, so it wasn’t difficult.

“That’s good,” she said.

I put the pants leg back down, and she went back to work.

Alfred came out of his office, and gestured to me. We had our meeting, and then I headed toward the door. As I did I turned to Harriet.

“What was that about?” I asked.

“Oh, I wouldn’t go out with a guy who had white pasty legs,” she explained.

She went back to what she was doing, and I left. As I did, I thought to myself, Did I ask her out?”

He hadn’t, but he would.

Joe arrived home in Oct. and took up residence at the Great Northern Hotel–owned by renowned boxer Jack Dempsey. Simon and Kirby set up shop in a small studio room at Harvey Publications, and for the first time a staff complimented them. Ken Riley, Jack Keeler, and Bill Draut, all colleagues with Simon in Washington joined up with lettering wizard Howard Ferguson to form the nucleus of the new studio. Joe would later lament that he didn’t at least give DC a chance to match Harvey’s offer, and he thinks it left a bad taste in some DC editor’s mouths. As it was when Jack started working for Harvey, DC cut his output way down to just a few pages a month.

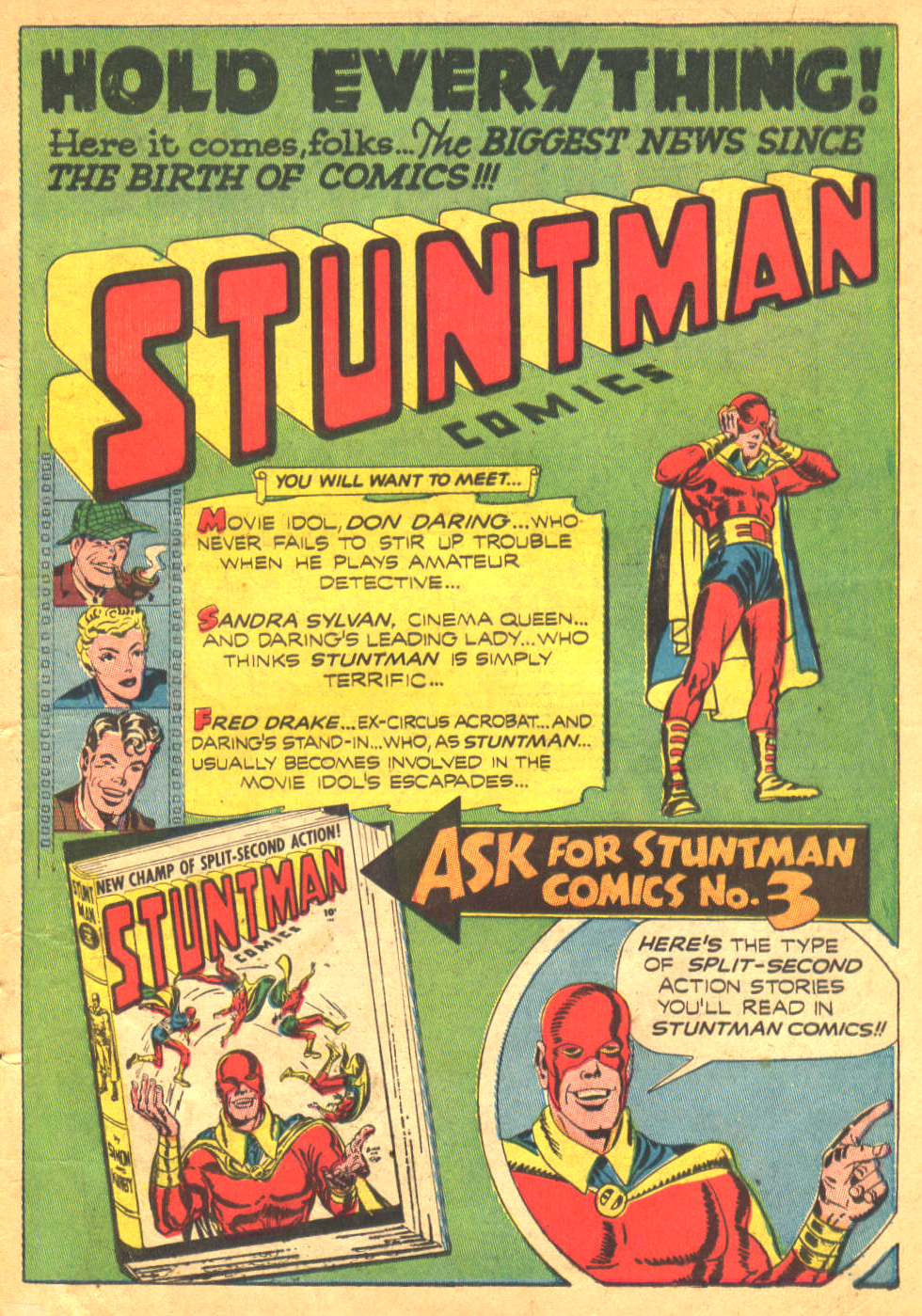

Advanced notice of new strip by the biggest names in comics Simon and Kirby

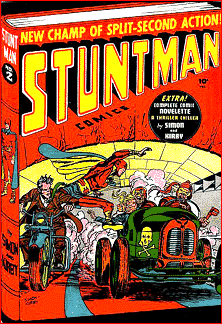

Everything was set; they would hit the ground running, full bore, no hesitations while editors hemmed and hawed a la DC. Joe had thought long and prepared well for this moment. Joe and Jack went straight to their strengths; costumed acrobats, kid gangs, exotic locales, and non-stop action. Advertisements in Harvey’s books highlighted a new title “Stuntman! Written and drawn by the biggest names in comics! –SIMON and KIRBY—their first book since their return from the fighting fronts.” Once again the Simon-Kirby brand was the selling point for quality comic stories-despite Joe Simon never seeing the front.

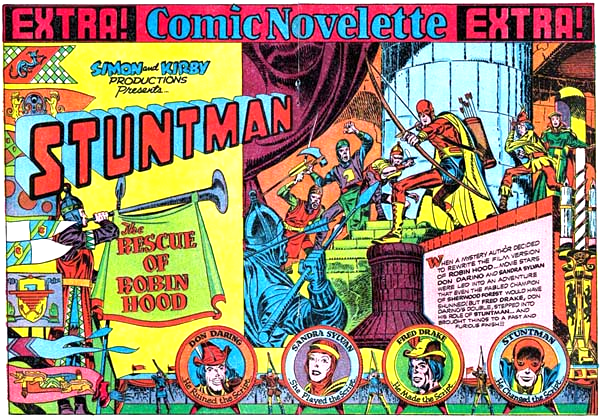

Stuntman was set in, and part of, the world of Hollywood. Fred Drake, was a circus trapeze performer whose partners were murdered. While tracking down the killer, he learns that he is an exact double for Don Daring, one of film’s leading men, and amateur detective. Daring was the typical S&K leading man, obnoxious and conceited, but since this was going to be a recurring role, they softened his manner with humor, and made him more a buffoon than a lout–the perfect foil for the clever, athletic, laconic and heroic Fred Drake.

Loved the vehicle to vehicle jump

Since they are both on the hunt for the same killer they team up. Don offers Fred a job as his stunt double. They are soon joined by the beautiful, but bemused actress Sandra Sylvan. After another brush with the killer, Drake decides that he must go undercover, and retrofits his circus costume into a masked crime fighter’s costume. The origin story ends with the newly outfitted avenger tracking down the killer, and saving the bumbling Don Daring and faint-hearted Sandra Sylvan from an attack by ever-present Hollywood man-eating lions. Stuntman berates the hapless actor for his less than sterling detective work. “Next time, you may not have a ‘stuntman’ around to double for you,” Drake is overheard telling Daring and the headlines in the morning’s newspaper read “STUNTMAN SOLVES CIRCUS KILLINGS.” This is how a new hero should be introduced!!!! This was Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr., all rolled into one character. Stuntman #1 was cover dated April, 1946. This was S&K using their love of Hollywood for all it’s worth.

There were three Stuntman stories and two back-up strips; Junior Genius by Jack Keeler, and the Furnished Room by Bill Draut. Also tucked in was a two page text story of their other new creation.

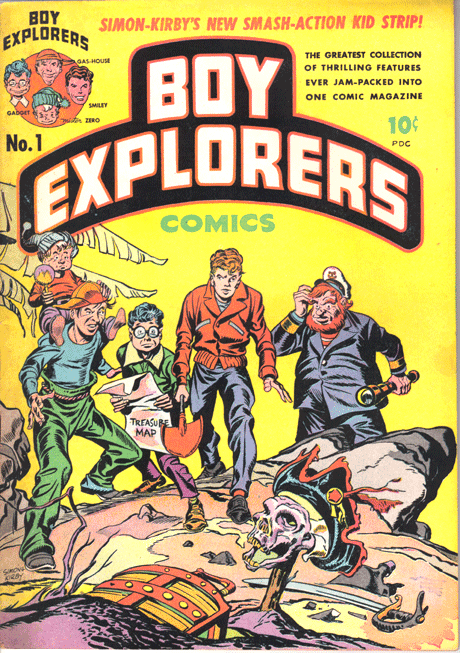

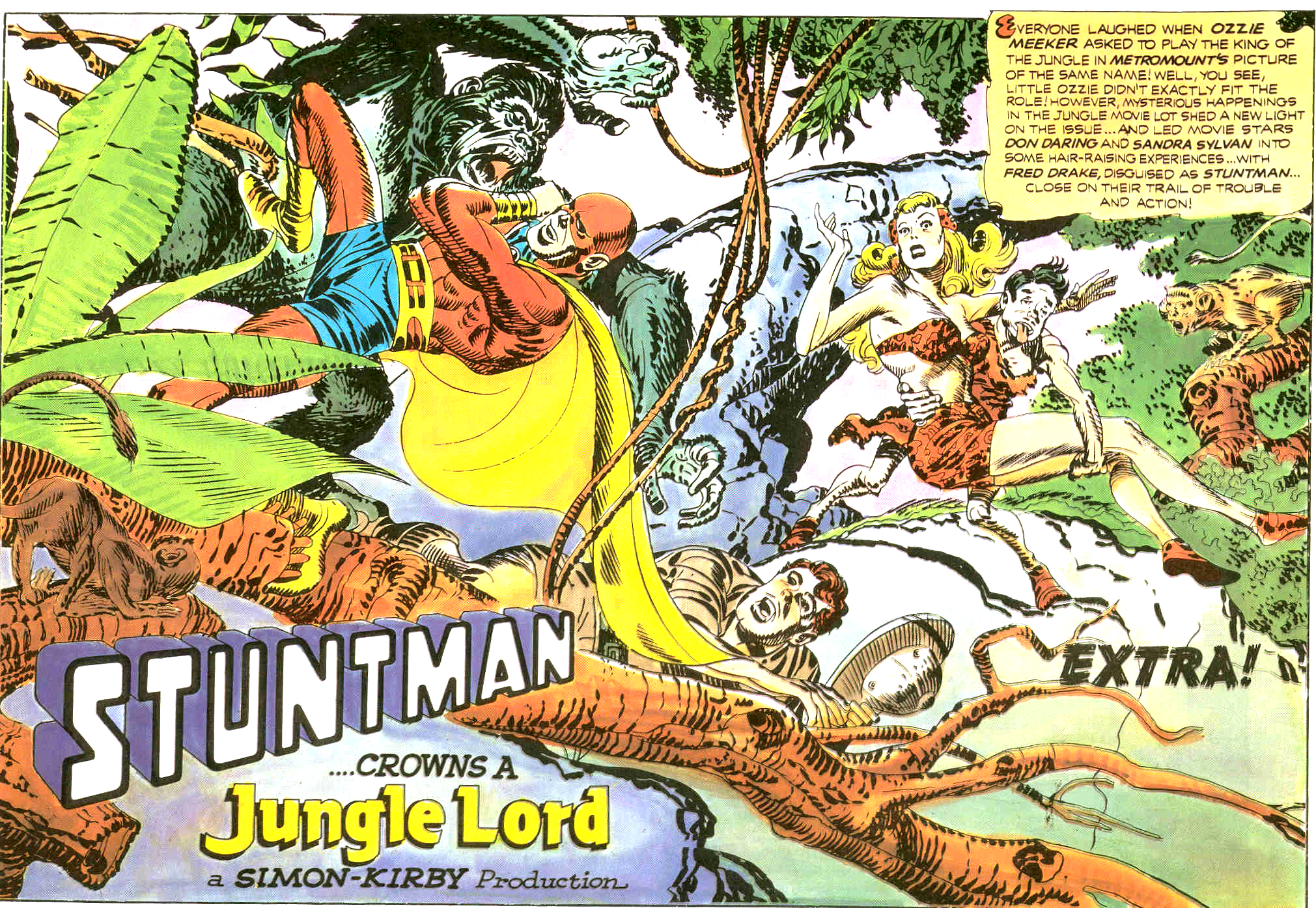

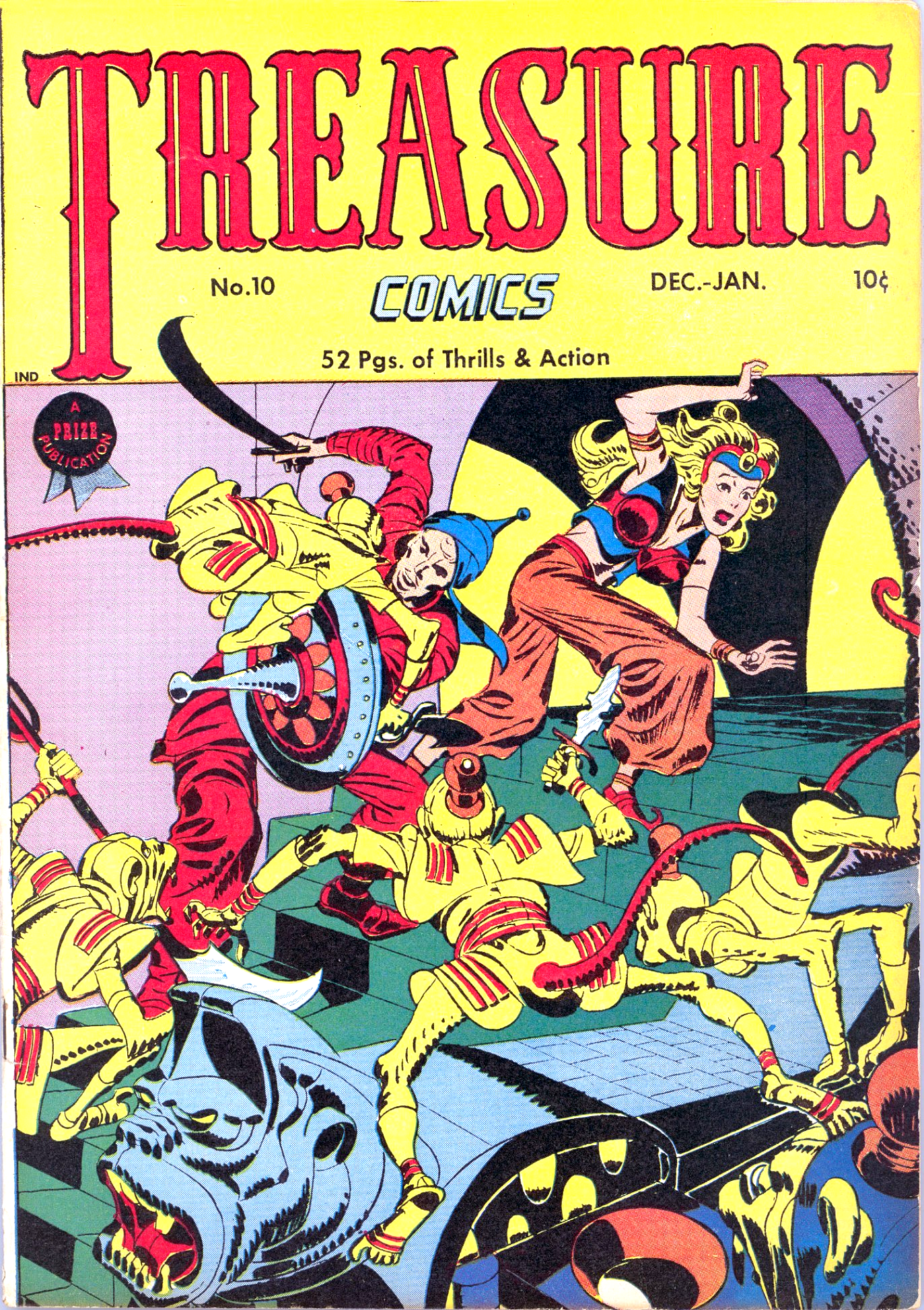

dark and dense and look what he’s reading! – never ending action

The other new title was Boy Explorers; a classic S&K kid aggregate, this time under the guidance of Commodore Sindbad. To save the Commodore from an unwanted marriage, the boys must embark on the “Seven Tasks of Sindu San”, a series of dangerous adventures and return with selected treasures. This update of the 1001 Arabian Nights Sinbad tale was a crackerjack, roller coaster thrill ride full of that unique blend of Simon/Kirby slapstick action, mixed with sci-fi, mythology, exotic locales, and a wacky assortment of adversaries. Boy Explorers #1 was dated May, 1946. They even managed a trip to the moon.

Concurrently, Harvey published a Stuntman story in their anthology title All-New Comics #13; (July 1946) a neat little stolen jewelry caper. This book also featured ads for Stuntman #3 and Boy Explorers #2. Neither would ever see print.

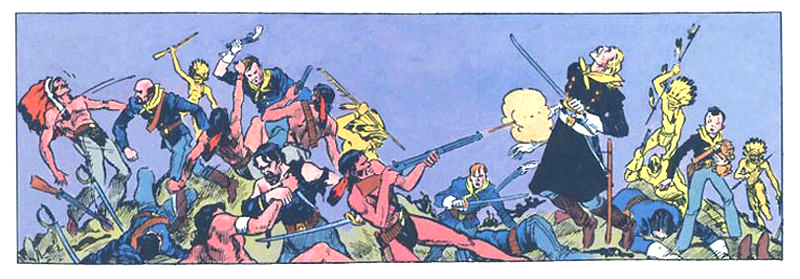

S&K never slowed down: Stuntman vaulted from adventure to adventure saving the ever-bumbling Daring and enchanting the beautiful, but slightly air-headed Sandra Sylvan. The Boy Explorers travels took them to the South Seas, lost islands, and even the Moon. The plots were lean and silly. Very reminiscent of the Hope and Cosby” road” pictures; they allowed Joe and Jack to plug in their every cinematic fantasy. Cowboys, gangsters, Robin Hood, jungle tales, Amazons, dinosaurs-they all got the S&K treatment, with double-page splashes, great cinematic perspectives, and lush, detailed backgrounds. This was the pinnacle of S&K swashbuckling and derring-do. Jack was also busy at DC doing mainly Boy Commandos.

Shades of Treasure Island

Jack’s art was hitting a new high point; added to the power and fluidity was an improved eye for background detail. He added a lushness of texture and an evolved sense of depth as his perspectives became more extreme. Joe’s inking became heavier, with a more stylistic approach to shadows and cloth folds that gave added weight to Kirby’s pencils. Howard Ferguson would add another level of dynamics with his decorative narrative panel flourishes, and multi-font style banners. The cover to Boy Explorers #1 is a classic example. They returned to two page centerfolds of spectacular and mass excitement.

2-page splashes are back

Promises of things to come

The boys all had their own back-up strips filling out the books. The back-up tales were an interesting amalgam of genres. Jack Keeler did “Junior” Genius, a humor strip, while Bill Draut provided Furnished Room, The (Red) Demon and Calamity Jane. Ken Riley drew Danny Dixon, Cadet. Joe even picked up the pencils and produced three back-up strips; Vagabond Prince, a greeting card poet turned crime fighter, The Duke of Broadway, a Damon Runyonesque look at the underbelly of the Great White Way, and a humorous boxing feature titled Kid Adonis.

Jack on Boy Commandos, Joe on Kid Adonis meets Superman

Joe doing Will Eisner on Duke of Broadway Bill Draut cuts his teeth on Red Demon

Joe did most of his drawing at the hotel later at night, the office at work was a mite crowded; with all the others working in what Joe Simon called a “small office supply room and the executive men’s room”. They were in full production mode and building inventory. The boys were in it for the long haul.

Joe Simon solo – Growing family Neal and Susan

On Dec. 6th 1945, Roz gave birth to their first child, Susan. Jack was ecstatic. Meanwhile, Joe got up the nerve to ask that flirty secretary out, and things were heating up. Things couldn’t be better, when disaster struck!

Heavy advertising but never followed up

The end of the wartime paper restriction was the signal for all of the comic book companies to increase production. All the publishers from the big boys at DC, Timely and Fawcett, to the smaller firms like Fox, Gleason and Quality jumped at the chance to add new titles, and increase printing runs. Well over a hundred new titles were published between September 1945, and September 1946. The trouble was that the retailers– the newspaper stands, and the Mom and Pop drug stores–didn’t have the physical space to take in all the new titles. They were forced to pick and choose which titles to carry, and all too often the choice would be the familiar and well known titles from the larger companies. Truckloads of new books were being returned unopened due to lack of space. Just as fast as the glut of new titles happened, the bubble burst and a major contraction in the business occurred. Small companies went belly up when they couldn’t repay the money fronted by the distributors, while many had to fall back and regroup.

later ones a digest sized

Even DC, the industry leader was forced to address the problem. In an amazing letter to advertisers and distributors in late 1946, DC tried to spin the “slump” by using carefully selected stats and dates to put the best face possible on the situation:

COMIC MAGAZINE SALES ARE AT ALL-TIME HIGH!

“There has been some talk about a “slump” in newsstand comic sales and it is about time the record is straightened out. A recent increase in returns has blinded many dealers to the fact that comic magazine sales are at an all-time high. Speaking for ourselves, “Superman-DC Publications, we can say with full authority, sold 26,264,000 copies in the first four months of 1945 and 34,020,000 copies in the same period of 1946 — a gain of 29 per cent!” During the war-time magazine shortage, returns disappeared almost completely. Today, as business adjusts to normal conditions, returns are again a problem. They are a handling problem to wholesalers and dealers but to publishers like ourselves they represent a dollar-and-cents cost. For this reason alone you can be sure of our cooperation in holding returns to a normal minimum”.

Historian/artist Coulton Waugh explained his observation of market share and natural limits;

“There are approximately one hundred and fifty comic books which jam red and blue elbows together on the newstands, fighting for space to shreik in, and this factor may help keep the number from expanding to any great extent. Mortality is high among new comics.

Joe says he saw the writing on the wall, and tried to warn Kirby. For his part, Jack didn’t believe it could affect them. To him, S&K was 10-foot tall and bulletproof. Stuntman #1 hit the stands in late January or early February 1946, followed by Boy Explorers #1 in March. By February, Alfred Harvey ordered a complete halt to production. Simon and Kirby was shut down! The warehouse was overrun with returned and unopened stacks of the new titles. Only two issues of Stuntman and the one issue of Boy Explorers ever made it to the streets. For the next six months, Harvey would assemble the inventoried stories and bleed them out little by little. They averaged only one book a month published for that period.

Joe and Jack were devastated; never had a project started with so much promise only to die on the vine. To make things worse, DC had cut back on Jack’s production. For the next year, Jack would provide art for just one issue of Boy Commandos, plus a few covers for Star Spangled Comics. In fact, for the 8 months following Harvey’s implosion, Jack Kirby – the human dynamo – would be limited to 42 pages of comic art, and 6 covers.

Joe recalls; “Jack drew a handful of Newsboy Legion stories late in 1945, and some Boy Commandos adventures in 1945–46. I had done a few things for DC while I was in Washington. Once I was back in New York, I joined him on the Boy Commandos stories.”

The sales slump wasn’t the only problem; the social outcry was reaching a crescendo. In 1946 the General Foundation of Women’s Clubs focused their efforts on the comic publishers to the point where some of the publishers created a self regulating body. Unfortunately the social groups were left unimpressed due to the lack of participation and took their complaints to other bodies.

So yes, it should be noted that the industry was reeling, but it was not in its last throes of life. Sales had fallen dramatically, but not to death’s door.

Artist Coulton Waugh explained in his history of the comic strip and comic book The Comics (1947, McMillan)

“We should understand that comic books are not, on the whole, appendages to the world of the newspaper strips, nor are they supported by advertising, like a good many other periodicals. They stand on their own pink and green feet as a separate, unique, publishing accomplishment. How this is possible is indicated by the fact that they have been selling at a rate of forty million a month. Comic books are a self-sustaining business, a very profitable and important one.”

It was only in comparison to their meteoric success during the war that the industry now looked in peril. DC was correct in their industry wide article, though returns had increased; the industry was still selling mountains of books. What was needed was a smarter approach to printing volume, and a new focus for the industry away from the almost accidental dependency on the wartime desire for superhuman fantasy fare. Waugh talks about this unexpected explosion.

“In their history, (periodical publishing) the magnitude of such a development was unsuspected for quite a while after the books had appeared. The drama in the stories came at precisely that wild and roaring moment when, into the lives of the matter-of-fact business men who were handling the books, burst an unprecedented blast of public demand, millions of voices all screaming at once, Let ‘em come!”

It was the unexpected and unexplained dominance of the superhero in the comic market during the war years that made the sudden drop so dramatic. Though a source of bemused irony to Mr. Waugh, he could not deny that those colorful little pamphlets had created an important and viable industry.

Once more from Coulton Waugh;

“We had better add comic books to the list of important discoveries made in the last ten years. This hurts many people; it doesn’t seem possible that anything so raw, so purely ugly, should be so important. Comic books are ugly; it is hard to find anything to admire about their appearance. The paper–it’s like using sand in cooking. And the drawing; it’s true that these artists are capable in a certain sense; the figures are usually well located in depth, they get across action…But there is a soulless emptiness in them, an outrageous vulgarity; and if you do find some that seem, at least funny and gay, there’s the color. Ouch! It seems to be an axiom in the comic book world that color which screams, shrieks with the strongest possible discord, is good. Even these aspects of comic book art are mild and dull when contrasted with the essence of it; the layout, the arrangement of ideas and that goes, too for the ideas themselves.”

Crotchety old man but he could draw

Waugh had little trouble showing his utter disdain for the comic industry yet even he couldn’t deny its impact. One wonders if he had ever read a Simon and Kirby book. The bottom line; comics were just great for the businessman and bean counters but not yet fit discourse for those with delicate sensibilities. Waugh never tried to hide his prejudices; instead he spotlighted and explained his choices. It may have been a history, but it was not exempt from his prickly views. His disdain was not just focused on comic books—he was not a big fan of many of the adventure newspaper strips. He declared that Alex Raymond’s characters in Flash Gordon “have an empty look” that “show little of their hearts and minds.” He thought Milton Caniff suffered from a bout of “smart alecky” with “static figures” and his plots “artificial and snarled” He really disliked Zack Mosely’s Smilin’ Jack calling it “one of the most painful jobs to look at in the business.” Surprisingly, (perhaps to save what little hair I have left) Waugh lavishes nothing but praise on the master—Hal Foster—of whom he gushed “the man was so good at his particular job that there remained little for subsequent workers to improve on”.

From the introduction to a later printing by M. Thomas Inge;

“Though intended as a study of one aspect of American culture, Waugh’s book itself has become a part of that culture through its influence on all the commentary that was to come. His was the enviable but difficult task of the pioneer, the first in the field. So he could lay down the guidelines and principles without fear of contradiction. He did it so well that The Comics still makes a legitimate claim to our attention and therefore deserves a continued life in print.” Waugh’s own prejudices are clear…comic books he found raw and ugly.”

Coulton Waugh was no fan of the superhero comic book, but he wasn’t an effete snob; he was the scion of a well respected New England artist family. He was a fine painter, textile designer, map-maker, and sometime cartoonist. He took over the fantasy strip Dicky Dare after Milton Caniff left. This was the story of a 12 year boy who imagined great adventures with historical characters like Robin Hood, or George Custer. He was also a comic historian, perhaps the first and he was an optimist. He ended his treatise on an upbeat note.

Dicky Dare started by Milton Caniff taken over by Waugh

“In spite of all the learned arguments of the college professors who endorse the lurid form of the comic book, the great mass of American people have been getting thoroughly annoyed at the alarming mass of cheap sensationalism their children have been buried under. These human torches and hornet men seem to have little connection with the sound values which the American people, generally speaking, strive for, and it seems that the people in a number of ways have been making this clear to the publishers. An example of the things so many people object to, for instance, is the army of hooded and masked men, women, boys, and even girls, who were threatening to push the normal heroes off the stands. (Obviously heroes such as Dicky Dare, drawn by Mr. Waugh – ST) Why in the name of a free Republic, is all this hooding necessary? True, these people are always on the side of right, of democracy; but democracy’s justice does not need to mask itself. From the picture point of view—and this means a great deal in comics– such hooded people suggest the Ku Klux Klan more than anything else, the very reverse of the process of democratic law. Protests of many kinds, from many sources, have poured in, to the point where at last a change is taking place; the furious sensationalism of the super-people is not as popular as it was. A new and healthier trend is on the way. The big news of the moment is not the emergence of a new super creature; it is the growing in popularity of the gay, animal comic book of the general Walt Disney type, and the various titles devoted to teen-age interests.”

“Teen age comics are very normal and healthy as a rule. In addition, the animal group can develop fantasy, can supply the experimental adjustment to life through childish symbols, which the educators advise as good for the young mind. Another happy point—these are funny books; the super-screamers were not. And to laugh is one of our greatest national habits, one of our finest talents.”

Waugh may have been right, his problem was not that super-humans were bad or sensationalistic; his worry was that there was once a reason for these cartoons to be labeled “funnies”. The super-heroes weren’t funny. They lacked, or worse, were the antithesis of humorous. As Waugh mentioned, he felt that the funny animals or teen-aged tales returned to the idea of making kids laugh. One should note that Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Mighty Mouse, Captain Marvel Bunny and other anthropomorphic animals were rising to the top when printed by Dell, St. Johns, or other companies. Waugh was wrong; the next wave would not be funny animals, in fact, it was human relations in all their vulgar, animalistic horror. And Waugh’s fear of social uprising was accurate.

I hope you don’t think bad of Coulton Waugh, it was not my intention of belittling his opinions. I am not out to shoot the messenger. Waugh was not a grouchy old man endlessly screaming at the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn. His arguments against comic books were honest; he did know that they could be better. They were lowest common denominator entertainment that never required of the artists or the publishers to do better. Yes there were gems to be found, but they were amongst a huge stash of trite, ugly, and morbid books of their kind. Waugh did want better, and he attempted his own higher quality output. Coulton Waugh left Dicky Dare to his wife Odin Burvick to create his own strip. He titled it Hank. Unlike most strips of the time, there was no handsome, athletic, adventurer, and sexy slinky, exotic femmes. Hank was introspective and wheel chair bound due to losing a leg during the war, looking at the world through self-absorbed eyes. His stories were attempts at finding and understanding ones place in society and coming to grips with loss. The differences weren’t just thematic. Waugh used a very decorative and florid style that seemed to isolate Hank’s own lack of movement. He sometimes avoided the static rectangular panels and exaggerated the motion. He added in black dialogue balloons with white words to give them depth and solemness. He brought a level of social conscious and conflict. He humanized it somewhat by using upper and lower case fonts for the dialogue.

Hank

The humanity and pathos was overwhelming, Waugh admitted that this was an exercise in “social usefulness” and as such lacked exaggerated drama, and action. Waugh’s attempts were sadly cut short due to too many years in front of a board. He stopped when his eyesight finally failed him. Hank was printed in the left leaning New York tabloid PM, and had a rather small circulation. Not a hooded avenger in sight, Waugh tried to walk the walk. Though short lived, PM magazine also featured the art of Dr. Seuss, Crockett Johnson and Jack Sparling, and the writings of Ernest Hemingway, James Thurber and Erskine Caldwell. It was often compared to the Daily Worker, though formatted closer to Gilmore’s and Gleason’s Friday magazine.

During this down time both Stuntman and Boy Explorers had a small black and white digest type book mailed out to subscribers, which featured inventoried stories. The cover explained that for the present emergency, newsstand sales will be temporarily discontinued and subscribers would be sent these small digests. There was only one issue per title sent out.

Joe was scrambling, for months he and Jack had no work. The industry was changing; the super hero genre was dead. World War 2 was over, and with it went the need for fantasy power figures to handle overwhelming evil. The interests of the populace were now more mundane and close to home. Being the premier costume hero creators meant little. For S&K to come back, they would have to reinvent the business to reach a new market and reinvent themselves.

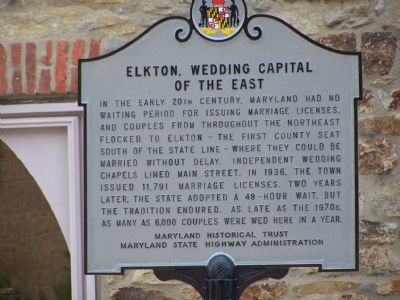

But comics weren’t Joe’s only thought. On June 3, 1946, Joe and Harriet Feldman slipped away to Elkton Md. and got married. Elkton, a small town just below the Pennsylvania border, had become famous for quick, unquestioned marriages due to Maryland’s lax marriage laws. Hundreds if not thousands would sneak over the border to get hitched.

Like out of a romance book – still had a nice suit

As to the problem at hand they had to find work and form a new base to operate from. One of the few genres that continued unabated after the war was the crime genre. Lev Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay was a good selling title that seemed to be growing. Lev Gleason was a rarity, a comic publisher who wasn’t Jewish or shady. What he lacked in shadiness he made up for in political passion. Son of a well to do Protestant Massachusetts doctor, he attended Harvard University but dropped out during WWI.

Returning from the war he found himself working for Eastern Color Printing Company. Lev was a salesman for Eastern when Max Gaines approached the company about publishing a pamphlet sized cartoon book. Within a few years, Lev became the editor for Tip Top Comics. In 1939, after the success of Superman, Lev partnered with magazine publisher Arthur Bernhard and formed Silver Streak Publications.

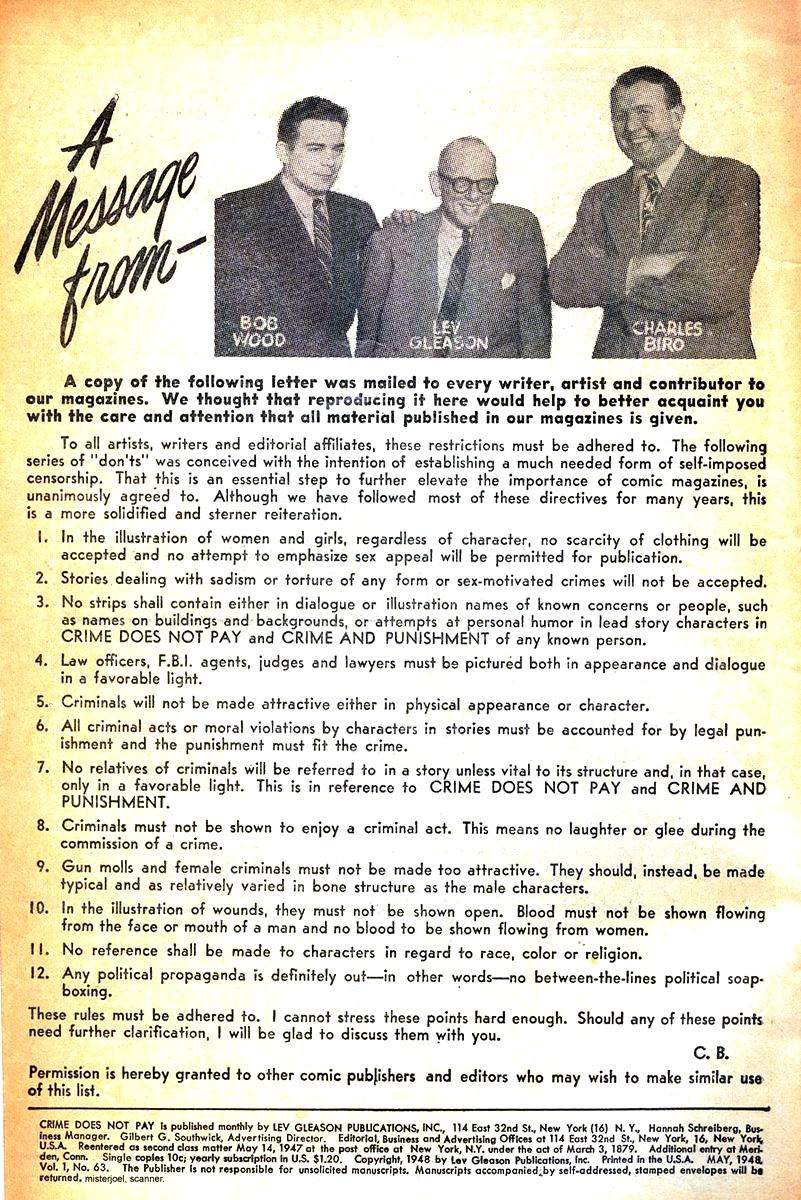

Looking debonaire – the boys at play

Lev Gleason was also a friend of Communists. He had become involved during a two year sabbatical to France after the WW1. He worked for some front magazines and collected for Communist front companies. He assisted Dan Gilmore on the left leaning Friday magazine. He had attracted the ire of the F.B.I. and had a thick file at the bureau. He was fined by the H.U.A.C. for his part in a suspected Commie organization. In the FBI file they noted his part in publishing comics. (thanks to the Comics Detective website) Their response was not so positive. “..the publishing of the cheap pulp paper type comic booklets is a common practice and is considered a racket in the publishing fraternity in New York as little capital is needed to engage in this type of business, which is not highly regarded by reputable publishers.” (Obviously they never saw the bottom line of these publishers)

The company had its first hit with a character named Daredevil, a long-running costumed crime fighter. Its next big success came in 1942 with a comic focused entirely on crime. Crime Does Not Pay was the first and best of a long line of crime comics. Its initial success was good but not great. Other companies took note, and slowly copied. Gerard Jones, in his book Men of Tomorrow (2004 Basic Books) stated; “It (Crime Does Not Pay) sold solidly all through the war, but not well enough to inspire imitations. Then, in 1947, as America’s fascination with crime and corruption intensified, its sales soared. By the end of the year, it was outselling even Captain Marvel and Superman. It seems in fact, to have stolen much of the super-hero audience.”……”After years as the only crime comic on the stands, by late 1948 Crime Does Not Pay was just one of forty.

But the crime genre came with some baggage. As Jones notes; “There was pungency and narrative vigor in the best of them, but there was a sickness of sprit in them too. Comics had a freedom to indulge in gore and cruelty that the more closely watched media of movies, radio, and “slick” magazines didn’t and they tapped into American appetites that those other media hadn’t revealed. The success of the material was unsettling to the very men who made and sold it—so much money for such seamy stories peddled under such smarmy, phony messages about the folly of crime. There was viciousness in the crime comics that assumed sadism in the reader and, in its exquisite intensity, revealed sadism in the artist.” Gleason even tried to blunt this complaint early with an editorial fiat.

Gleason trying to pre-empt the Comics Code 1948

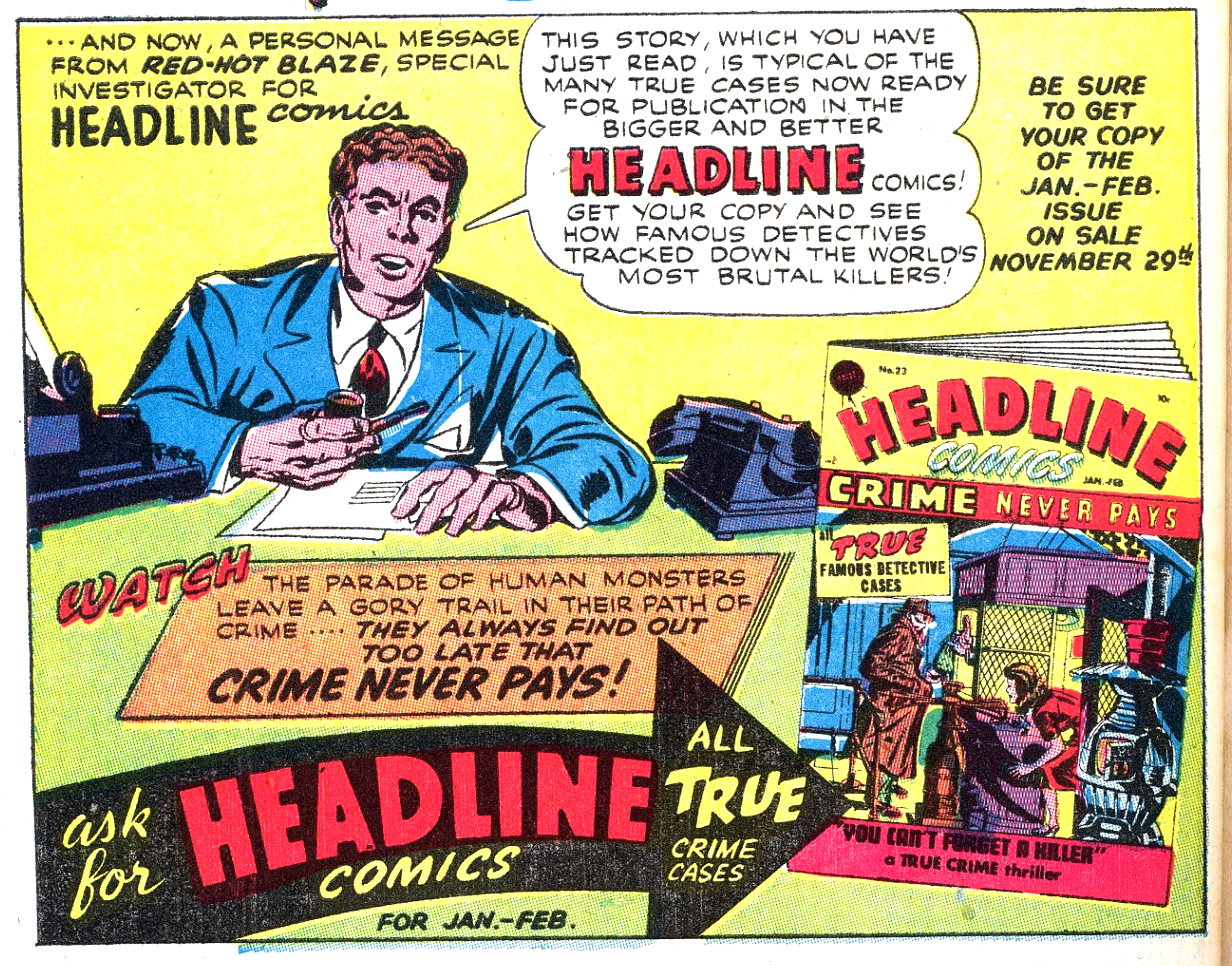

Joe approached Crestwood Publications with an idea concerning a news reporter who specialized in sensational murder cases. The catch was that the reporter, Red Hot Blaze worked for a pulp type comic magazine and the featured artist resembled Jack Kirby. Blaze first appearance was a 6 page tryout back-up story in Treasure #10 (Dec. 1946) and featured one of Kirby’s best covers along with an advert blurb showcasing the new series in Headline Comics–another Crestwood title. Several oddities about that advertising blurb; first they show the issue (#23) with a Jan/Feb cover date. #23 in actuality had a delayed Mar/Apr cover date. The cover shown in the blurb was not the actual cover to #23, which showed a convicted gunmoll holding off the cops by threatening a hostage. The blurb cover was actually used for issue #24 (May/June 1947). It’s amazing how much inventory Jack and Joe had accrued that a cover meant for a May dated issue had already been drawn, inked and colored for an advertising blurb back in a Dec. dated book.

Nice blurb—wrong cover wrong date

Now this is action, hateful little monkees

Crestwood was a small publisher which S&K had crossed paths with during their freelance days in 1940 when they rebooted Prize Comics. Owned by Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleir, Crestwood never had more than a few titles at one time. Their most popular title was Frankenstein, the Dick Briefer created strip that expanded out of Prize Comics into its own title. Headline Comics was a low selling anthology title populated by easily forgettable super-heroes like Atomic Man and the kid gang, the Jr. Rangers.

Crestwood comics full of S&K in and on the comics

Three months after Treasure #10, Headline Comics #23 (Mar. 1947) hit the stands with a total do over. Gone were the superheroes and adventure stories, to be replaced with cover to cover crime tales penciled and inked by Jack and Joe. Often narrated by Red Hot Blaze, these stories were violent and bloody. These tales were billed as “all true” famous detective cases and starred real gangsters and mobsters. Babyface Nelson, John Dillinger, Ma Barker and other Depression era hoods populated these gritty, hard boiled tales. S&K filler crime stories would appear in other Crestwood titles like Prize Comics and Frankenstein. By the late Forties one in seven comic titles were crime themed. Certainly not the humorous tales Coulton Waugh envisioned, but the focus was on physically normal people as opposed to ultra steroidal hulks.

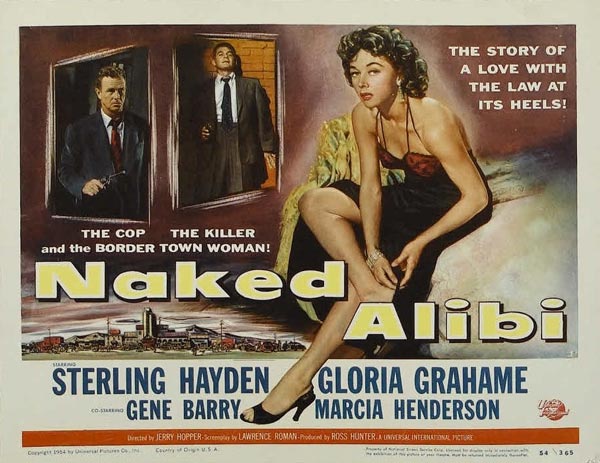

Jack and Joe were back at work, they attacked these crime tales in a heavy noirish style never seen before from the pair. The faces were heavily shadowed; the clothing was heavy, with deep folds and dark shadows. The backgrounds expanded the heavy geometric patterning in the shadows and became claustrophobic with the detail and spotting of blacks.

It is obvious that the pair were taking their cues from the Noir style films that became the rage after the war…. the badder the girl the larger her eyebrows. Jack even fulfilled a dream when he played a gangster on one of the covers. (Joe played the cop)

Bad girls with gats and eyebrows

Crestwood wasn’t the only company that Joe had contacted. Hillman Publishing was another small time magazine publisher that had scraped by during the war years on the strength of Hollywood pulps, automobile manuals and a couple of comic book titles. Its bestselling title was Airboy Comics which starred the titular teen-aged globetrotting flyboy with a miraculous plane named Birdie. Interestingly, during the war Hillman cancelled many of his pulps and comics to publish a glossy girly digest named Pageant, only to return to comics after the war. The peripatetic editor Ed Cronin bought into Joe’s feeling about crime books and turned over Clue Comics – a rudderless anthology title that started as a showcase for the heroic Boy King and the kid gang Jackie Law and the Boy Rangers- and evolved into a showcase for the Gunmaster, a sharp shooting private dick type. Starting with issue Vol 2 #1 (Mar. 1947) S&K supplied crime stories. With the second issue; they also took over the Gunmaster strip. With their fourth issue, the title was changed to Real Clue Crime Stories. It seems that Jack and Joe drew more historically inspired stories dealing with crime in the 1700 and 1800’s for Hillman; perhaps the reason for adding “Real” to the original cover. It seems their inspiration was the 1928 book Gangs of New York by Herbert Asbury—a recalling of the many street gangs and gangsters prior to Prohibition and the mafia. This book was also an inspiration to a later film by Martin Scorcese. And just to round out the feast to famine and back, DC had started re-commissioning new work from Jack for Boy Commandos.

Hillman comes thru

Joe and Jack were back in the game, producing 50-60 pages a month between Hillman and Crestwood. Harvey was also starting back up the road to full recovery, and S&K inventoried strips and reprints began showing up in Harvey titles. One, a back-logged Boy Explorers story features an easily recognizable Frank Sinatra clone, trying to hide out from his many female admirers; he joins up with the boys and is shipwrecked ironically on the Amazonian “Isle Where Women Rule”; a nice play against type story. Joe swears that they were never paid for these stories. Another comic industry lesson reinforced–even your friends will screw you.

A year and a half later – teasing and kidding at Hilman

It should come as no surprise that Jack Kirby, crime reporter, once again returned to his BBR roots for another take on the problems of pinball and back store gambling. In issue #24 of Headline Comics in a story titled “Grim Payoff for the Pinball Mob,” Kirby once again centers on the youthful gambling being forced on the candy stores and the mom and pop shops. Once again the law cracks down on the thieving mobs and a strident DA sends the guilty up the river. Kirby’s drawings of candy stores being packed with pinball machines could have been taken directly from the BBR report on petty gambling and Kirby’s earlier Newsboy Legion tale. But the crime titles were simply treading water, Jack enjoyed portraying the mobsters and his all-too familiar Depression life, and they sold reasonably enough, but held no lasting interest for Joe.

Hillman did allow the boys to try their hands at other genres. For the first time since his Lincoln syndicate days Jack drew some Bigfoot funny animals. Lockjaw the Alligator and Rover the Rascal appeared as filler strips in Punch and Judy Comics. They even took over another funny animal strip from Tony Dipreta called Earl the Rich Rabbit. In Airboy Comics, S&K took over the aviation strip Link Thorne-The Flying Fool. Kirby’s fondness for flying once again found root and they energized this mundane aviation strip and produced another action classic. The strip was reminiscent of Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon, complete with sexy oriental assistant and even sexier femme fatale competitor. But S&K’s strip preceded Steve Canyon by a month or so. Truth be told, after the war there were a plethora of adventure strips based on fly jockies in business in Asia. Harvey Publications even had their own Flying Fool strip.

Perhaps most important, Hillman gave Joe free rein on an original title, one of Coulton Waugh’s preferred teen-aged titles. One character that had never slowed down was Archie, America’s favorite teenager. With the end of the war, this title had found a renewed vigor. Joe decided that they should try their hand at teen humor. The result was My Date. #1, July, 1947. It starred the teenaged wunderkind Swifty Chase and his main girl Sunny Daye and their riotous romantic adventures with the insufferable bore Snubby Skeemer, and pesky Housedate Harry. In typical S&K fashion, the first story centers on Hollywood and Humphrey Bogart in particular. Swifty and Sunny help Humphrey escape from his manager so he can elope with the much younger Chandra Blake-mirroring Humphreys real life escapades with Lauren Bacall. A lone teen humor strip “Pipsy” even found its way into Laugh Comics #24 Sept. 1947, an Archie Publication. The foundation was set. Two months later, the dam broke.

Flying Fool great adventure and a true femme fatale

Previous – 8. Call To Duty | top | Next – 10. The Girls Take Over