Previous – 7. The Well Diggers Legacy | Contents | Next – 9. Picking Up The Pieces

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

CALL TO DUTY

In early June, Kirby received his draft notification. “I was drafted June 7, 1943. I found out the same way as everybody else: They sent a telegram. You get two free telegrams from the Army: One to tell you that you are drafted and one to tell your wife that you are coming home in a casket. Sure, I was drafted, but I didn’t mind going. You didn’t complain about it because it was the thing to do. All my friends were gone, even Joe.” They gave up the Carlton Place apartment, and Roz would move back with her parents for the duration. On June 21, with a final tearful kiss from Roz, Jack turned in his #2 pencil and picked up a gun. According to Kirby; “My card was stamped NAVY. And then some guy came in and said ”We need six guys for the ARMY.” I swear it was stamped NAVY and you know I feel to this day I was meant for the NAVY. This guy came out and being a loser, I was one of the six.” Coincidentally Mort Weisinger, an editor at DC who bedeviled Simon and Kirby while they were at DC, boarded the same embarkation bus. Jack forever swore it was Mort’s way of further tormenting him.

There’s a couple of juvenile delinquents mid-’45

Camp Stewart was the largest Army facility east of the Mississippi, encompassing over 640 square miles of Georgian lowlands and swamp. Originally set up as an anti-aircraft artillery training center, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it became a primary training facility for the Army. It was here that Jack Kirby would receive his basic training and then spend a year at special training. “I tried to stay out of the Infantry like mad. So they first sent me to anti-aircraft, and I thought that was pretty rough. Then I went to Ordinance and I became an auto mechanic and I told them I took 2 years of it at school, I used to lie under the wheels and I used to knock on the wheels and the guy thought I was working.”

Though Jack would constantly explain that he was a famous artist, the Army saw fit to make him an auto mechanic. Now Jack may have been great at drawing huge machines, and constructs, but in reality, he was one of the least mechanically gifted people alive. His friends wouldn’t drive with him for fear of their lives. His kids swear he couldn’t even change a light bulb. It was so bad that even the Army soon realized the error of their ways- and the Army doesn’t admit mistakes easily- and reassigned Kirby as a rifleman. Jack’s attempts at working for Yank Magazine, or other military publications were all rebuffed. Yet one publication did take note of Kirby’s presence. The Savannah Evening Press, a local newspaper in their October 1, 1943 edition had an article that spotlighted Kirby. It was a small article praising Jack for his work on Boy Commandos- it even mentioned Jack’s birth name of Kurtzberg, though it was misspelled Kurtzerg. An expanded article would appear in the Camp Stewart Newspaper a week later. They spelled his name correctly.

Army life wasn’t much to Jack’s liking. He wasn’t built for military precision and uniformity. He couldn’t understand why he couldn’t punch out this burly guy constantly yelling in his face. ”You’d get ten years for punching a sergeant so I couldn’t punch a sergeant.” And he couldn’t draw. How could he survive without a pencil in his hand and paper in front of him? “I hated it there and they always gave me a hard time. I am not a guy who likes to be disciplined. I hate discipline of any kind except the kind of discipline I make for myself, like when I draw. If it is not right I’ll redraw it 19 times until I get it right, but Army discipline I wasn’t ready for. “Stand straight. Get up. Lay down. Do this. Do that.” They would wake us up at two o’clock in the morning and make us hike 50 miles, 25 miles up and 25 miles back. That is a long walk with a full pack, a rifle and everything else—that’s a long walk without them. And at two o’clock in the morning, are you sleeping or walking? And you are doing this all on roads as rough as hell.

He needed an outlet for his aggression. He gravitated towards hand to hand combat. “I took judo. Out of a class of 27, just me and another fellow graduated.”

A thousand miles, and light years from his familiar surroundings of city life, the culture shock was overwhelming; mosquito swarms, pigs running thru the street, gators in the lakes. Jack could not fathom what life in the Deep South was like. “I met Southerners for the first time. That was a big experience. I didn’t know anybody who spoke like that. Well, they spoke like that in the movies, but here it was live and real. I met Texans.”

“The thing is that we all met. I met people from Georgia. I found people of my own religion living in Georgia. There are a lot of Jewish people living in Savannah and there were a lot of Jewish people living in other parts of Georgia, in all parts of the South—even in Texas. I realized that there were a lot of similar people living all over the place. I began to get a feel for the United States in a way I never had before. I could envision the United States as the American flag. The stars and the stripes–the meaning of it. Jack explained to Ray Wyman Jr, in an interview.

Roz would tell of a trip where she and her sister Anita visited Jack while he was stationed at Stewart. While visiting, Jack had arranged for a date for Anita, to be accompanied by a soldier friend from Texas. They were taking a bus to their destination when an older black woman entered the crowded bus. Anita graciously stood up to offer the woman a seat at the front, wherein the bus came to an immediate halt. When the driver demanded that the black woman move to the rear Anita protested. Both Anita and her Texan date were thrown off the bus, and when they returned to the base, the soldier friend told Jack, “I’m through with her; get her out of here!”

Anita was sort of high spirited, and Jack set up another date for her, this time with his sergeant, Morris Katz. It was hate at first sight; they fought for the whole date; pure oil and water. Three years later, Morris Katz would show up at the Goldstein residence looking for Anita, and they married soon after.

While Kirby was doing his service, Republic Pictures released a Captain America serial. Nowhere to be found were the names Joe Simon or Jack Kirby. It seems that Martin Goodman had given the rights to Cap to Republic free of charge, expecting the free publicity to make it worthwhile.

The 1944 “Captain America” film serial is a bit of an oddity. Unlike the new Chris Evans feature, or any other incarnation of the hero for that matter, it totally abandons the basics of the comic book character. In place of US Army Private Steve Rogers the striped suit is filled by District Attorney Grant Gardner. There’s no Super-Soldier Serum, no massive patriotic shield, no temple wings, and there aren’t even any Nazis. It’s an odd cross between the superhero genre and the noir/crime serials that Republic Studios put out around the same time. Simultaneously entertaining and a little confusing, it poses an odd question about what a superhero film should look like.

The choreographed action and brashly structured suspense lend a momentous energy to this entertaining serial. It’s not just that they spent a ton of money, which they did. After going 22% over budget, “Captain America” ended up costing Republic around $220,000 and is the most expensive serial they ever made. Yet instead of just tossing around effects left and right, every moment of explosion and destruction is used perfectly. Guillotines, exploding cars, and massive bulldozers come and go across the screen, raising the bar for each successive moment of suspended climax.

It’s been claimed that the large budget convinced Republic to get out of the serial business.

By June ‘44, the camp originally built to house 40,000 swelled to over 55,000 soldiers awaiting the build-up for D-Day. Jack, now assigned to Company F, 11th Infantry under the overall command of Gen. Patton left for Europe in the middle of Aug. “I think we reached England at nightfall. We landed in Liverpool. England was in a terrible state. They were still suffering from the Blitz. The German Stukas and bombers had dropped bombs everywhere. The people were still sleeping in the subways—the Germans had made a mess of Liverpool—but we didn’t stay there long; they immediately took us out of Liverpool and we reached Gloucester. I remember a lot of walking and a lot of waiting. We were tramping through the streets there and were on our way to another POE. I got a glimpse of the English countryside when we reached the embarkation area near Dartmouth and it was like a garden; it was the most beautiful thing that I have ever seen. We were there for about 2 days, then we left for France and landed on Omaha Beach”. He stepped foot on the still body strewn shores at Omaha Beach, on Aug. 23rd. From there he quickly met up with the rest of the 11th Infantry as they marched through Eastern France.

After the grinding landing on D-Day, the allied troops had moved quickly across Northern France, and thru Paris. The success was such that as September approached, there was a great feeling of optimism among the commanders. The German’s were backtracking so fast that they had little time to resettle and dig in to stop the advances, and when they did the Allied forces quickly overwhelmed them. “They moved us very quickly into the hedgerow country and into waiting trucks, put us on more trucks and drove down so many roads that I could never tell you where I went. After a while you just forget how long it took and where you were. But I remember the villages that we drove through. Those villages are still etched in my memory, really, because they were in utter ruins. Utter ruins! You could see the former beauty of these places and I felt very sorry for the former inhabitants because I am certain that many of them were killed. I felt sorry because I knew that we would probably add to the destruction, but it was a necessary sacrifice, one that was apparent to everyone. We bypassed Paris—I never saw the city—and joined the rest of the forces that were being gathered together for Patton.”

With control of Northern France, and reinforcements now firmly in place, Eisenhower made the controversial decision to split up the Allied forces and make a pincher move on the heavily guarded German military industrial centers in the Ruhr, and from there on to Bastogne, and then to Berlin. Many of his Generals had counseled him to keep the Army together and make a direct assault with overwhelming forces and crush the enemy in one fell swoop. Yet Eisenhower was wary, he still feared the German’s could regroup and mount a rear offensive looping around from the South. By splitting his forces, he protected his southern flank, and with two fronts forced the Germans to spread out their remaining forces. Eisenhower decided he would send the largest segment of the army on the more direct northeastern route through Antwerp, above the Ardennes, and a smaller army on the more circuitous route south and then east through Metz and Saar. This smaller army was Patton’s Third Army Corp, a faster, more mobile force known for covering territory very quickly. This was to be called the Lorraine Campaign.

Spearheaded by the famed 761st battalion– the all-black tank regiment that would lead the fight from France through Belgium, and into Germany– Patton’s Panther’s better known by their battalion name The Black Panthers with their bold motto “Come Out Fighting”.

This elite tank group would engage in a record 183 continuous days of combat, clearing out numerous German held cities, freeing concentration camps, and inflicting over a 130,000 casualties to the Germans. Their fighting spirit and never say die attitude emboldened the fighting men and the honor of meeting up with the Russian allies fell to the 761st after breaking through the Seigfried Line. A sad note that one of their leaders could not join up with the battalion; their moral leader Jackie Robinson, the college football great was fighting a court-martial due to his refusal of giving up his seat on a public bus. Jackie was cleared of all charges and left the service with full honors, He would be heard from later.

“I was a replacement–a replacement for people who had already been wounded or killed. I went into action right away, my outfit was on assault. We were heading towards Metz, and the objective of my outfit was to take Metz.” Kirby reminisced.

Patton’s Brain Trust

Almost immediately there were problems. The Armies were advancing so rapidly that they outran their supply system. The Generals fought and fumed over who would get the gasoline; Field Marshal Montgomery won out. Gasoline supplies were dangerously low, and re-supply ground to a halt. General Patton, though warned of the situation ordered his officers to continue on, but by Aug. 28 they came to a stop, just west of the Meuse River. Though his main force couldn’t move, Patton ordered small expeditionary forces to cross the Meuse bridges and try to feel out the enemy strength. By Sept.1 they had made several beach heads across the Meuse, and on to the west bank of the Moselle River, just outside of Metz, but that was as far as they got, on Sept. 2 the Third Army was at a stand still, there was no gasoline to take the tanks and trucks across the Moselle bridges. The German generals were told to hold position at any cost.

The resulting lull allowed the Germans to do what Eisenhower most feared; it gave them time to regroup, dig in and bring in reserves. From then on, the march towards Metz would be a bloody fight, over farms and embankments, small towns and well built fortifications, criss-crossed with rivers and canals. Victory would be measured in yards, not miles. It would be one of the bloodiest episodes on the road to Berlin.

To make matters worse, the rainy season for the Lorraine Valley begins in September, and in 1944, there would be three times the average amount of rain. The clay terrain would turn to a viscous texture that swallowed up tanks, trucks and marching feet.

The armies were now at a stalemate staring across the Moselle River; every attempt by the Allied forces to cross it was met with a fierce counter-attack that drove it back. The rains made land travel difficult, and the rising river made boat travel treacherous.

Jack told Will Eisner. “The only one who took me seriously was my Lieutenant! He says “Kirby, you drew Captain America,” he says, “you‘re an artist.” I said, “Yes, I’m that kind of artist.” He says, “Well here’s a map. Take the map. We’re both going across the river tonight.” The Moselle River, this was, outside Metz. He says, “When you see a tiger Tank, you put a cross where it’s been.” He says, trying to find these tanks.” And of course, that’s what I did.”

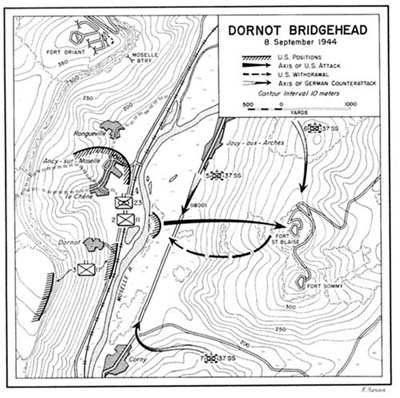

On Sept. 8, a small Allied force attempted to cross the Moselle at a small hook in the river called Dornot. Their target was a fortification named Fort St. Blaise, one of several Maginot Line forts retrofitted by the Germans after taking control of France. It was a well built medieval fortification on top of a bluff overlooking the river. Among this force was Kirby’s Company F of the 11th Infantry. The rain was horrible, but under cover of blistering artillery fire Companies F and G worked their way across river. They gathered at a small patch of trees on the east side and formed a horseshoe shaped line of trenches. German resistance was light, but whenever there was a lull in the Allied artillery fire, the Germans would lob mortar shells with deadly accuracy. In late afternoon, the two companies broke from the trees and made a frontal assault up the hill towards the fortress. During this assault, two more companies made their way across the river and occupied the horseshoe trenches.

From U.S. ARMY IN WORLD WAR II – The European Theater of Operations-Lorraine Campaign – the official documentation as compiled by the Department of the Army:

“The forts themselves were strangely quiet, and the Americans suffered no loss until a sniper killed the commander of Company F near the top of the hill. Here the infantry came to the wire at the north fort (Fort Blaise), cut it, and then, faced by a moat and a causeway barred by an iron portcullis, drew back to radio for help from the artillery. While so disposed the two companies suddenly were hit by the 2d Battalion of the 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment which swept in on both flanks and filtered through to their rear. Captain Church called for Companies E and K to come forward from the east bank, to which they had crossed during the afternoon; but they could not advance through the heavy enemy fire now traversing the slope, and the two forward companies began to withdraw, leaving dead and wounded marking the path. For nearly three hours the infantry crawled back through the gauntlet. The company aid men tried bravely to give help to the wounded left behind but were shot down at their tasks. Most of the survivors did not reach the clump of woods near the river until 2300, (11 PM) here joining the rear companies in the defense of the minuscule bridgehead.”

“East of the woods a highway paralleled the tree line and in the darkness enemy Flak tanks drove up and down, spraying the bridgehead with bullets and shell fragments. Fortunately, the German tanks, though protected by “bazooka pants,” would not close with the Americans in the woods.”

The Allied troops on the west side of the Moselle were helpless to send reinforcements. The area was too small for larger vehicles to maneuver, and they were being shelled by large German 88’s that made boat crossings impossible. For two more days the four Companies were left to fend for themselves. It was decided that the Allied forces would move further down river and hope to make a safer crossing while the Germans were occupied with the four companies at the tree line.

“Time after time the German grenadiers came forward in close order, shouting “Heil Hitler” and screaming wildly, only to be cut down by small arms fire from the woods and exploding shells from the field guns on the opposite side of the Moselle. But each attack took its toll of the defenders in the horseshoe. The wounded were forbidden to moan or call out for aid, so that the Germans would not know the extent of the losses they had inflicted. The mortar crews abandoned their weapons, whose muzzle blast betrayed the location of the foxhole line, and took up rifles from the dead. A lieutenant operated his radio with one hand and fired his carbine with the other. Nearly all the officers were killed or wounded when they left their foxholes to encourage the riflemen or inspect the position. Each night volunteers carried the wounded to the river, crossed them in bullet-ridden and leaking assault boats, then returned immediately to the firing line.”

Kirby would tell in an interview with Warren Reese about an incident. “I had a guy die on me once, during the war, and he looked up at me he said, “What the hell happened? What happened?” And here I was, just a schmoe from the East Side…from New York City, y’know, and what do you answer the guy? I told him, “You happened.” See? And that was real. It got me to think how valuable human beings are, and at that moment I discovered my own humanity, in that moment, I discovered everybody elses.”

“The plan to sideslip the meager forces in the 11th Infantry bridgehead, opposite Dornot, and join them with the 10th Infantry was abandoned when the regimental commander reported that “the men are all shot.” Since the 10th Infantry now had a foothold on the east bank of the Moselle, General Irwin ordered the evacuation of the Dornot bridgehead.”

Just a little walk in the park

The report of the loss of all men resounded across the battlefield with no correction ever made. Jack Kirby had his baptism by fire, and in the fog of war, thought dead.

The official report would state that this episode was:

“….colored by countless deeds of personal heroism and distinguished by devotion to duty. Thirty-six separate assault attempts had been hurled against the men in the horseshoe without breaking the thin American line. Indeed, on the morning of 10 September, the Americans had the superb effrontery to send a demand that the Germans surrender, The War Diary of the 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment noting that the Americans promised such a concentration of fire as their enemies had never seen before if they did not capitulate forthwith. The determined infantry and their supporting artillery killed an estimated six hundred Germans in this bitter fight, and the toll of enemy wounded was probably very high. Detachments of at least four enemy battalions, reinforced by tanks and assault guns, were thrown against the bridgehead in the three-day battle, making their attacks with a ferocity and determination that astounded the Americans.”

The remnants of the four companies made their way back across the Moselle River and rejoined the main line. Their casualties were so high that they combined together and became one new company. The intelligence was mass confusion. Kirby learned the lesson of the “fog of war”. He said; “Suddenly, there was my colonel and with my colonel was General Patton, and Patton looked at us and looked at a map. He says, “You guys are supposed to be dead, Why aren’t you dead? He was dismayed. Something on his map was wrong, because we were supposed to be dead. The Germans were supposed to have overrun us, and they had. We just didn’t like the idea.” “But like I said, I couldn’t hear most of what he was saying, except when he raised his voice and all the other officers stepped back like he was going to slap them. Of course, that wouldn’t happen in an American army, not in public at least where all the GIs could see. So, this went on for—I don’t remember, I was too frozen to care, but it went on for quite a while. I heard that Patton ordered replacements. He thought my outfit had been wiped out. So some foul-up I guess, signals crossed, messages mixed up; it happened quite a lot during the war.

The plans for Dornot—nothing went right

Shortly after Dornot, Kirby’s troop is sent to help out in taking an old fort southwest of Metz, no more than a kilometer from Dornot. Fort Driant—sometimes called Triumph– is another part of the old Siegfried line of medieval fortifications protecting Metz; made of reinforced concrete complete with a moat, underground bunkers and barbed wire. It sat on a hill and rained down withering cover fire on the troops below. Patton decided they had to take Ft. Driant and a direct assault was the best way. Kirby said that after a few days of stalemated fire, the Germany General came out to talk to the Allied General. The German commandant, dressed in all his finery told the general that the Allies should give up because the Germans don’t want to fight them anymore. When asked why, the German said that his men were ashamed of fighting such ill equipped, foul smelling and uncouth soldiers “they look like bums” “Look at them, they are all dirty, they don’t wear helmets, their hair is all over their faces….they are an insult to my outfit.” The Germans were a determined fighting outfit, and after too many losses, for the only time during WW2, Gen. Patton changed his mind and retreated from Ft. Driant. Driant was never defeated; when Metz was taken they voluntarily gave up. One soldier wrote about the weather and horrors of war. “A drizzling rain fell. Through the haze, artillery, rifles and machine guns worked without rest. The men crouched in trenches, in curious, strangely intimate warfare, often within the sound of the enemy’s voice. In the nearby town of Dornot, American and German dead lay sprawled together in too hot a corner for immediate recovery. Occasionally, when the rain lifted, Thunderbolt fighters whipped in to dive-bomb and strafe strong points. “

Driant was a failure for several reasons; The weather didn’t permit aerial coverage. The men were not trained for this type of direct assault on a fixed position; they did not have the proper equipment and Patton’s intelligence let him down. He was told the fort was manned by a small poorly trained and tired staff while in reality, the defense had been taken up by a group of well trained, arrogant, and resourceful units from a nearby officer candidate school full of fanatical Nazis. They were bright, shiny, and well entrenched at the strongest of the Metz’ forts; they weren’t trained to lose.

After the battle, the combined count of E and F was less than a hundred men. When asked by high command, the Captain told them; ”The situation is critical. A couple more barrages and another counterattack and we are sunk. We have no men, our equipment is shot and we just can’t go on. The troops in G are done, they are just here, what is left of them…The enemy artillery, especially the 88’s are butchering these troops until we have nothing left to hold with. We cannot get out our wounded…” The soldiers didn’t care if it was a win or loss; they just wanted the hell out of that meat grinder. It was a small bit of land that they could easily go around. The enemy wasn’t going anywhere; they were surrounded and cut off from supplies. Let the Jerries camped in that big mound of dirt sit and play with themselves, they had other targets to hit.

The undefeatable Ft. Driant—high on a hill

For the next two months it continued in this pattern. Constant attacks by the Allies, only to be repulsed- two steps forward, one back. “War is a sequence of events; you’ve probably heard that there were these long periods where there was nothing to do but to sit and wait. Then you walked a lot, and then there were those times that you knew that any second it was curtains. I had a few of those moments. Most of the time was when they were shooting 88s at us; the German 88 was an anti-armor gun, but it was also a very effective anti-personnel weapon and they used it quite a lot on us. You could shoot hundreds of 88 rounds in a minute; a battery of 88s would churn the ground around you and pulverize bricks in an instant. The 88 was a fairly big shell, not like long-range artillery, but big enough that if you came into contact with one of these things you’d never see tomorrow. Once we came up against some of these things; they were all coming in and stepping up and shooting, pumping lead. I was lying there just shooting away with my rifle—that’s all I had. My whole division was pinned down. Eventually our artillery cleared them out, but not until a bunch of us were killed. It was a holy mess. You could hear the shells fly past your head like a high-speed mosquito. That was when you knew you had a close call. But not just the sound, you could feel the pressure. I experienced that more than once.”

The mighty German 88 could be mounted on rails, on trucks or stationary

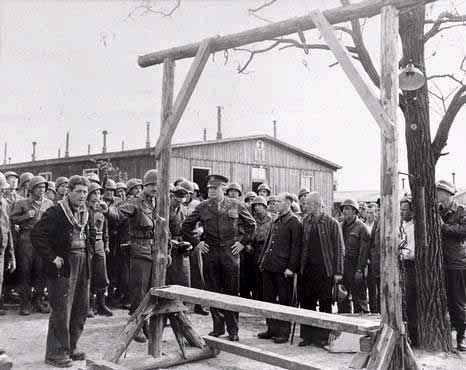

In early 1944, Russia had come across the first provable concentration camp. That was Majdanek. Though empty and the prisoners reassigned, the carnage visible was catastrophic. As Patton’s army crossed Western France, it became obvious that the Nazi’s had peppered France with a large system of concentration, and work camps, Some were large, like Fort de Queuleu, while the area around Metz and Nancy contained many smaller individual camps as well as sub camps of larger compounds like Orhdruf. The soldiers often came upon these out of the blue with the last of the guards running away and looking for shelter. Most of the prisoners—at least the healthier ones had been reassigned to Germany or Poland with the advancement of the US Army. Yet some were found full and horrible, containing some of the worst of the human hunger dogs commanded by the Nazis.

Captain Alois Liethen, an intelligence officer was one of the first American soldiers to see the camp, wrote the following to his family in a letter dated April 13, 1945: He toured with Gen. Eisehower noting the atrocities as they were found. Eisenhower promised full reporting so that no one could ever deny or sugar-coat what was found. With them traveled a group sarcastically called “The Ritchie Boys” a group of Jewish refugees who became translators and interrogators of the found Nazis.

The quarters which they had were about as bad as I have ever seen. In a building about 100 x 30 there were from 200 to 250 men and their bunks were less than two by two by six — just like pigeon holes along the whole wall. I didn’t even go into these buildings because of the fact that there were definite signs of infestations of typhus bearing lice as well as many other communicable diseases. Bathing facilities were just non-existent, but that is not the worst of it — when a man was killed or died of beatings he was simply stripped of his clothes and these were reissued immediately to some other living cadaver. Shoes were out of the question and all of the footwear was a wooden sandal — not even so much as a whole wooden shoe.

As long as I am writing a horror tale I might as well describe some of the people who were in charge of this camp. The commandant (a man whose name I knew back in the states and who I am looking for now more than ever was an SS Hauptsturmführer BRAULING, and his right hand man was another SS man by the name of STIBITZ. Their favorite pasttime together with one or two other camp officials was to go out to the burning pit with a bottle of whisky each where they would sit and watch the burning of the weeks accumulation of dead bodies while they joked and drank their whiskey. Personally, the stench of the pit was enough to drive me nuts and a bottle of whiskey might have been a good thing for me while I was there. I have smelled a lot of foul odors — like out at the rendering works and other places — but this one was the worst. Evidently they were in such a hurry that they didn’t get enough tar and wood on the last pyre for there were about fifty half burned cadavers lying there in chars.

As I have stated this is not the first one I have seen — I saw another which was a more or less refined version of a concentration camp — this one was in the vicinity of Metz. Here, that is in the one near Metz, were kept the pure political prisoners and they had better conditions and the crematory was a fancy thing, not unlike a bake oven which they showed in a series of pictures in LIFE some time ago. At this one I was mildly surprised and I don’t think that I even mentioned having seen it — this latter one tho is really getting into the real thing. And, when one considers that this place was just a branch unit of a bigger one, well, then you can well imagine what the larger ones are like.

The vision of these horror pits was nothing ever to joke about. The effect was chilling. Jack Kirby would occasionally mention just such a camp, yet for this anecdote alone he never laughed or embellished to make it more palatable. He told it straight and sadly. He never placed a specific name to this tale.

Captain Liethen and Gen. Eisenhower inspect camps note gallows

While on patrol one day an older man with a gray wispy beard approached him. The man looked inquisitively at Jack and slowly said. “Are you Jewish?’

“Yeah, I’m Jewish.” Jack queried back, unsure of who was asking.

“Come with me” beckoned the old man

Not sure who he was following Jack moved forward slowly. They approached a small enclosed wooden tower.

“There….there” the man pointed anxiously with shaky fingers.

Jack stared at the encampment. He saw German guards fleeing at top speed, yet not too fast to forget to scream epithets at the G.I. After the Germans had cleared the area, Jack and his men approached. He opened the stockade hoping to find a few recent prisoners. What he saw astonished him. Hundreds of old, starving, pitiful prisoners came forward hoping to get relief. These were the sicker, more elderly workers not up to being reassigned to other camps, so they were left to fend for themselves. These were the absolute dregs, starving, tattered, and sickly.

Jack just stared at this horror, his mind numbed by the sight, he just muttered. “Oh God! Oh God! Over and over.

How did people let this happen?

The camp near Metz, which Captain Liethen referred to in his letter, was Natzweiler–Struthof in Alsace, which was discovered by American soldiers in September 1944 after it had been abandoned. This was a small sub-camp of the infamous Struthof Gulag. Metz, with its heavy medieval fortifications, its central railroad and many factories had many such camps to put the people to work. As the Allies neared prisoners were sent across the border to even worse camps in Germany and Poland. At the Fort de Queuleu camp just west of Metz, they uncovered a mass grave with over 20,000 corpses—perhaps the worst case in France. Jack would occasionally draw a concentration camp in his war books, yet he would never gloss them over or spoof them up for laughs.

There was to be a slight lull in the fight for Metz in Oct. as both sides sought to secure their position and prepare for the major assault on the city. Yet this period was a busy one for the 11th. They would march through the farms and small towns looking for German patrols. They had constant unplanned close range skirmishes when opposing patrols crossed paths. The enemy was close enough to shriek epithets at. There was the constant cat and mouse games with enemy snipers, and well hidden booby-traps. “Most Americans have an image of war—especially that war—that it was a carefully planned event; groups of men—groups of professional fighting men—going up against other professional soldiers, moving in columns, aiming their rifles, all under the orders of their commanding officers. Well, let me say that guys are guys no matter what the circumstances may be and different rules apply. We called each other names all the time; we were cursing each other in English, German, French, Hebrew; I had quite a large vocabulary by the time I got back—I could cuss somebody out in four different languages. Sometimes a shot was never fired but we’d still be yelling at each other to ‘go to hell’ or ‘go sh*t on yourself’; but you never said anything about somebody’s mother, not unless you wanted somebody to take a potshot at you.” Jack Kirby occasionally served as a scout, separated from his main group for hours, as he searched for enemy placements, and made maps of the forward area. He would string communication cables. There would be frightful minesweeping duties, clearing paths for trucks and heavy equipment. “I was a Scout in the infantry. If somebody wants to kill you, they make you a Scout. So, I was a Scout. I don’t know who wanted to kill me—maybe somebody that I upset somewhere, I don’t know. You don’t pull that kind of duty just because you’re a nice guy. Nice guys don’t get Scout duty. Maybe I was the new guy, so they said, “Give Scout duty to the new guy.” That’s probably what happened. You don’t pick some guy that you like to be a Scout; you’ll never hear the end of it.”

The anxiety and tedium was broken only by the infrequent letters from back home. Jack told biographer Ray Wyman: “I would go into these towns that nobody had yet, and there would be German patrols there, and I would head the patrol and we would scout around this God-forsaken town, and we would mix it up with the Germans. And there would be hell to pay. And then we would get back to our lines, and they are passing out the mail. I was dazed you know, by this time. It was a kind of post-anger; I hadn’t finished with the situation yet and was still in the throes of the most vicious intentions when I came back to this mail. They were insane but beautiful love letters. They were so beautiful that I couldn’t believe it.” But mostly there was endless marching, followed by standing watch in knee deep mud or sleeping on the cold wet ground. The weather had turned cold, and the rain continued. The only change was the occasional reprieve when the forces were rotated and rested for a day or two.

U.S. ARMY IN WORLD WAR II – The European Theater of Operations- Lorraine Campaign;

“General Eisenhower, in a visit to the Third Army headquarters on 29 September, had set forth the policy of a continuing rotation of front-line and reserve battalions in order to rest the tired divisions and get them in shape for a future offensive. ….. As troops came into reserve they were billeted in the shell-torn Lorraine towns and villages, given clean clothes, and-if they were lucky-trucked to Nancy, St. Nicholas, and other leave centers for a bath, a movie, or possibly attendance at Marlene Dietrich’s USO show, which, was even more popular than Bing Crosby’s Third Army tour had been in early September. But the men in the line lived under continual rain and in seas of mud.”

Jack recalled: We were stuck in one of those spots where the enemy was just plastering us. They were ripping up the earth with heavy machine gun fire, tearing us up with 88’s. They opened up some kind of an offensive, or they were just plain sore at us. It was the end of the world. Guys were flying through the air, guys hitting the ground. They were ripping everything in sight- trees, bushes, the entire shoreline. We didn’t know what to do, so we lay there, and a guy crawls up to me from out of the rear, and says, “Take five guys and crawl back about two hundred yards and there is a truck waiting- and go see Marlene Dietrich!” I’m looking at this guy like he’s a nut. I figured the war had got him and I should say something nice to him, but I was sore because I was scared. Everything was going up–the whole shoreline was now a ragged chewed up bit of earth. I mean, it was chewed up and more was coming in. This guy says, “Do what I tell you, take five men” I did what I was told, so I picked five men who were just as amazed as I was. I said,” We’re going to see Marlene Dietrich- and these guys thought I was nuts! But this was our big opportunity, they would go nuts too. So they followed me, and we went back, and there was this truck.

Fine looking G.I.

The truck takes us seven miles back to a ruined church. She gets out of a car filled with officers, about 6 guys get out, and then Marlene. They must have been sitting on her. We’re sitting there and I’m falling asleep because I’m overtired, and Marlene Dietrich comes out. She’s dressed in a knitted wool cap and long G.I. underwear. That’s all she’s got on, and she’s playing this friggin’ saw and singing “See What the Boy’s in the Back Room Will Have” It made the war very human for me. When I woke up, she was gone.”

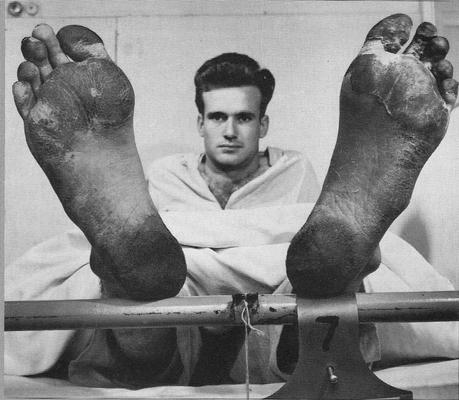

Late Oct. would see the fighting intensify as the Allies prepared for the assault on Metz. In early Nov. the rain got worse, and the Moselle River began to flood, the terrain was almost impassable and the saturated clay soil sucked in boots and shoes till there was no way to keep dry and warm. A dam, holding back the rain water had been breached and extra water flooded out entrenchments for both sides. The 11th Infantry was still recovering from its early battles when they lost much needed clothes and shoes. Foot problems were taking as many men as the enemy. From the official record of the Lorraine offensive:

“Some winter equipment came forward during October: blankets, overcoats, new-type sleeping bags, stoves, and other necessities. Most of the combat troops had three blankets and an overcoat. But in extremely wet or cold weather this issue would be insufficient to protect the soldier properly, especially in view of an acute shortage of waterproof ground sheets and raincoats. Rubber overshoes, a critical item as the Lorraine plains turned to mire in the constant fall downpour, were so scarce that they could be issued only on the basis of one pair for every four enlisted men. Shelter halves, woolen clothing, and socks also were lacking in sufficient quantity.”

Wellington boots or rubber field boots had been created late in World War 1 to help fight frostbite common in the trenches of that war. When WW2 started the factory was revived in order to produce boots for the British military. With the additional feet of the Americans, the factory could not keep up with demand. The weather was taking its tool.

The major offensive began on Nov. 8, rain continued unceasingly. The walking troops were ordered to remove their rubber overshoes, as they made maneuvering difficult. On the night of the 10th, a cold front hit, and a light snow began to fall.

Slim and trim and looking for Huns – soldiers trying to avoid trenchfoot

“France is a terrible place during the winter. One day, I took my leg out of the mud and it was deep purple. This was before we had combat shoes. We had plain shoes; I had a battle with my own shoes. I had to break my shoe off, and before I could break the other shoe off I was out like a light! Unconscious, it happened to a lot of men in the field- you just keel over. On Nov. 14 the 11th joined up with the 10th Infantry in a push against a new German line of defense southwest of Metz. Jack Kirby wouldn’t be with them. The day before Jack had collapsed, probably while stringing some barb wire and been sent to a field hospital with a severe case of trench foot. Immersion foot, as it is now called, is caused when the feet become wet and cold while wearing tight footwear. The affected feet become numb and turn bluish. Advanced trench foot can blister and cause open wounds, which can become infected and turn gangrene. The infection period was commonly called “jungle rot” as it could eat large portions of the foot or toes. Jack’s condition was such that he was rushed to a hospital in Paris for immediate care where the doctors at first considered amputation. Trenchfoot was the plague of World War 1, but the medical profession had learned if trench foot was treated properly, complete recovery was normal, though it is marked by severe short-term pain when feeling returns. One soldier said that it became almost impossible to tolerate the pain. Luckily, Jack’s circulation began to improve. Soon he was transferred to a hospital in England. Full recuperation would take a long time, Jack prepared for coming home. Jack recalled; Don’t think I just got nippity-ippity frozen—they were frozen. It took them a year to even get back some of the original color.” I was in the hospital for several months for my legs and I was in the hospital for a little over a year waiting for my feet to recover. They were considering amputation; my toes were black, but I eventually recovered.”

Soldier with severe trenchfoot

Roz was frantic. The frequent V-mails from Jack had stopped. Then one day she got a telephone call from England. She was informed that Jack was in a hospital. When informed that his injuries were to his feet, she sobbed with relief and thought; “Thank God he’s OK!” Then self mockingly; “Thank God it’s his feet, not his hands.” Soon the letters began coming on a regular basis.

In a letter dated Nov, 22, 1944, Jack jokingly told Roz of his arrival in England. “Surprise! Am in merrie ole H’england again with my gazoola still resting ‘neath comfortable sheets and my brogans [feet] stuck daringly out in the ozone to defrost in gradual stages. Nice enough place – chow is good and attendance pleasantly given. Have certainly made the rounds since I last wrote you and am still uncertain as to the extent of this amazing situation… However, with the exception of a dull numbness in the tootsies and a rheumy drawing in the joints am still intact and functioning. Love you more’n ever. Hope you’re not worrying, Please don’t, honey. Jackson.

In another, dated Nov.25, 1944, Jack remarked about the lovely women who surrounded him at the hospital. “Dear Long Limbed and Lovely, “My brogans may be frozen, but my glands are steaming to a rapid high in Fahrenheit. Have reams of gorgeous Petty and Varga girls plus numerous other streamlined sirens preening themselves enticingly in the mags about me. Being a very virile type of individual, I’m afraid this contact with these captivating hussies is gonna be one to beware of biologically”. It was signed affectionately with his nickname, Jackson. It appears that that “virile” individual succumbed to that temptation and, true to his stated fears it was a blow to his biology. Like so many other soldiers, Jack had to take a series of four penicillin shots for being so social. Jack was a man, not a saint.

One memory not so easily bypassed, would tie Jack to England forever. It seems the British populace tried to pay back those wounded in battle. He explained how he came upon a 2000 year old Roman coin that he passed on to Neal. “Back in 1944, he explained, he had been pulled from combat with a dangerous case of frozen feet and frostbite and then sent to a hospital in Britain. English farmers would plow ancient coins up by the dozen and while they kept the gold ones they gave the lumpy lead coins to “the boys in the ward” as souvenirs of Europe.”

In Jan. 1945, Jack boarded a hospital ship ultimately headed for Camp Butner, home of one of the larger military convalescent hospitals. “I caught a cold in England and they wouldn’t let me go aboard; so I missed the Queen Mary and they put me on this goddamn tug, a hospital tug that went like this, back and forth all the way across the ocean. I heard that they gave us the best meals in the world, but I couldn’t eat them. I almost starved myself to death because I was so seasick”. At Butner he would undergo therapy and fill up his days doing maintenance at the motor pool, and complaining to the doctors about imaginary ailments. The doctors added Psychoneurosis and anxiety (inc. hypochondrias) to his medical diagnosis

In March, Roz traveled down to North Carolina for a much needed visit. She found her once burly husband slimmed down to a meager 130 lbs. “He was so thin!” she would proclaim. It seemed that seeing Roz again did wonders for him. Jack had been put on restriction for some rinky dink reason and couldn’t get a weekend pass. So Jack came up with a clever ruse. He flashed his medical card (which was the same color as a pass) to an uncaring guard and as Jack would explain. “I took it out like this, see? I held it so the guard couldn’t see the front. And there are all these guys, they’re going out to see their wives and girlfriends, too. It was a parade! So the guards, they weren’t taking the time to look at everything so carefully. I just walked out with the rest of them.” He met up with Roz at her hotel room and as Jack would say: “We didn’t even close the door.” Author’s note: Susan was born nine months later!

On Kirby’s military records, it would show Kirby with an AWOL violation, but since it was so close to his release, nothing ever came of it. “What were they going to do?” Jack would ask incredulously.

The war in Europe was finally over, and on July 20, 1945 Kirby was honorably discharged and sent home. Given a combat infantry badge, a European ribbon and a bronze star, he returned home a conquering hero. For the rest of his life Kirby would revel in relating his war exploits. Real or exaggerated it made no difference; the war had left an impact on Kirby’s psyche that would never leave. He had witnessed the butchery that men can do, and seen the bravery and shared the camaraderie with men of all faiths, and backgrounds. His stories were always representative of the humanity he found amongst the horror. “There is nothing that you would call “romantic” about war. “Sure, in the movies and on television they paint a great picture of the fellowship that it creates. I’ve seen war bring lots of people together, but I can tell you that the cost is extremely high: Not just in terms of lives, but in the human spirit.” “I think that we are diminished by war; our character as a race is somehow reduced by each war that we allow to happen.” He further stated; “Well, I can’t remember what happened yesterday; I could not tell you what I ate for breakfast this morning, but I recall the faces of everybody that was in my unit. I recall their names, I recall where they came from, I recall the manner of their speech and even the common everyday things they did; unimportant things that make the whole event real. That is how the mind works: It retains the significant events of our lives by memorializing the important moments. It happens when we are faced with events that are pleasurable and those that are unpleasant, especially when we are faced with danger—at times when our lives are hanging by a thread. It was like that nearly every day of the war. The threat was never far from our thoughts, I can tell you.” Jack did his duty, but the nightmares lasted a lifetime.

Previous – 7. The Well Diggers Legacy | top | Next – 9. Picking Up The Pieces