A Failure To Communicate – Part Seven

Thanks to Mike Gartland and John Morrow, The Kirby Effect is offering Mike’s “A Failure To Communicate” series from The Jack Kirby Collector. Captions on the illustrations are written by John Morrow. – Rand

Part Seven was first published in TwoMorrows’ Summer 2002 Jack Kirby Collector 36.

Detail from Fantastic Four #99 (June 1970), featuring the Inhumans (probably in an effort to reintroduce them to readers before they spun off into Amazing Adventures #1).

“Kirby is leaving Marvel.” Stan Lee passed this information on to the Marvel readership in one of his Bullpen Bulletins editorials, and with his usual glib self-deprecating charm reassured the Marvelites that, although Jack would be seeking his fortunes elsewhere, the best was yet to come. Young readers had no reason to doubt Lee; sales were still going up along much of the Marvel line, and by 1970 the foundation of the “Marvel Zombie” had been laid, as many unsuspecting readers robotically swallowed Lee’s flip preachings. Besides, Lee was still there, and Lee was the man, the creator, the innovator; Lee was Marvel, right? Professionals, hardcore fandom, and industry insiders knew better; they knew that, although Stan was indispensible, this just wasn’t another artist leaving—this was the foundation to the “House of Ideas,” and with a foundation gone, can a “house” stand for long?

As we’ve read in previous articles, Jack had reached a point by 1967 where he was fed up with Marvel, particularly with Goodman and Lee. He had seen his concepts and creations exploited and taken credit for by individuals who promised him much but delivered little or nothing. Goodman was becoming even more wealthy on mass marketing and merchandising the Marvel creations; whereas Lee continued to take credit for characters and concepts he had virtually no input on save to dialogue after the lion’s share of the plot and story had been fleshed out and drawn by the artist. Steve Ditko allegedly left for these selfsame reasons a year before, suggesting to Jack to leave as well, but Jack was still under contract and was still being promised incentives. By the end of ’67, however, Jack realized that outside of an increase in his page rate and contracts that were begun but never finished, he’d been shortchanged again by Goodman and Lee, his contract was coming to an end, and it was time to decide. Stay or go, but if he left, go where? As strange as it seemed, unbeknownst to Jack (or Stan for that matter), television would play an indirect pivotal role in Jack’s decision.

By the end of ’67, due to the tremendous success of the Batman TV show, investors began looking to comic book companies as reasonably good investments. Both Marvel and DC had good sales and had been in the business under the same publishers for decades. DC went first, being purchased by Kinney National, then Marvel was sold to Perfect Film and Chemical. In both instances, publishers Goodman and Liebowitz remained temporarily (approximately four years) as publishers to see through a smooth transition and pave the way for their successors. Lee of course was first in line at Marvel, but at DC things were changing that would eventually help smooth the way for Lee to lose his most valuable asset. During the ’67-’68 period many of the “old guard” of DC’s writers and editors were either retiring, looking elsewhere, or simply being let go. The end result would be that the new editorial structure at DC would be composed of their former artists, with one of their premier artists—Carmine Infantino— taking the helm as editorial director. Carmine knew about Marvel what industry insiders knew for years: That it was creatively driven by its artists, and he wanted to bring that to DC. That wasn’t all he wanted to bring to DC. He had heard that Jack wasn’t happy with his present situation, and what better way to dent the competition than to get their main gun and fire it back at them?

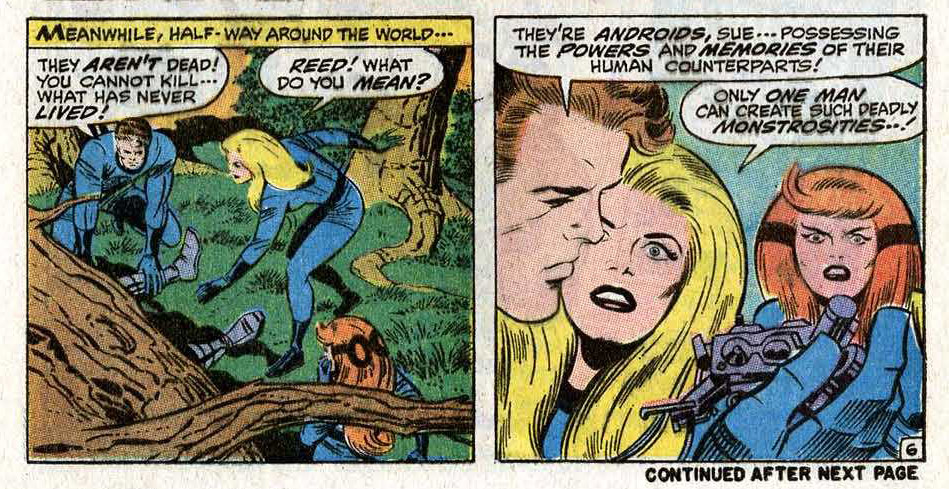

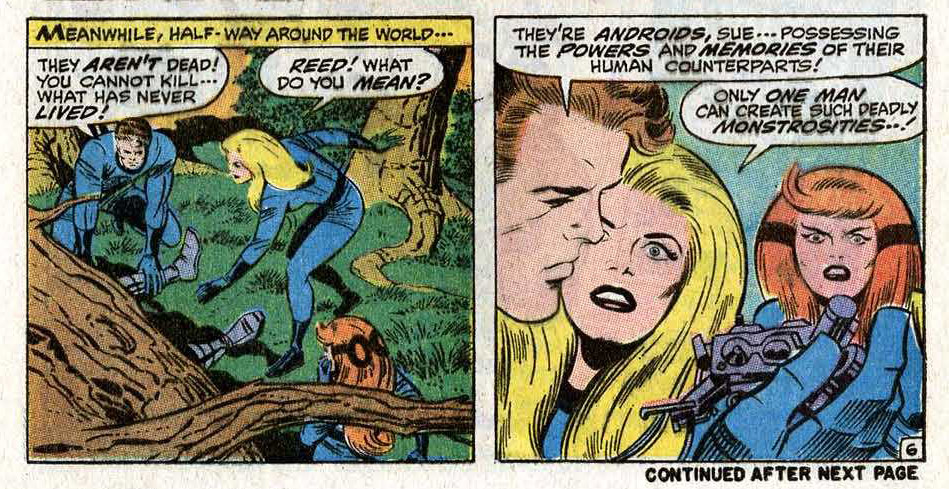

Panels from Fantastic Four #100 (July 1970). Reed erroneously states that only the Puppet Master is capable of making such androids, when he should’ve said it was the Thinker. Since they’d just done a Thinker story in FF #96, it’s an even sloppier mistake.

Meanwhile at Marvel, Jack had heard about the sale of the company (in late ’68) and both welcomed and dreaded it. He’d hoped that this might give him someone other than Goodman to deal with, but these were corporate investors who knew nothing about the comic book industry and even less about Jack. Lee was nervous as well; he now had more than Goodman to please and might have to prove his worth all over again. By this time Jack’s contract had expired and he was working page-rate, story to story. Despite his attempts to renegotiate for another contract, Jack was either rebuffed or put on hold (indefinitely); he knew he wasn’t going to see any percentage of merchandising or creative control of his work or even proper credit for it, but despite all that, Jack still would’ve stayed with Marvel if they’d only given him the thing that had always been most important to him: A promise of financial security.

More than anything else in his life, Jack had the constant need to make sure he could support his family. Family was everything to him; during this very time, Jack began taking steps to move out of New York where he’d lived all his life, and go to live in California (about as far removed from NY living as one could get), all for the sake of his family. Within the Marvel family however, Jack was becoming more and more isolated; Infantino had met with Jack during this time (while Jack was still in New York) and discussions began about Jack joining another kind of family.

While all of the aforementioned was going on, Stan was beginning to think of greener pastures. The success of the Marvel line had brought him the notoriety and recognition he so desperately sought during the years before the likes of a Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko came his way. Surprisingly, before his association with Jack and Steve which led to the Marvel successes, he languished for two decades pumping out average, topical, saleable plots and scripts for the Timely/Atlas books—but now by the mid-Sixties, he was being recognized by the general public as the creator of all these great characters and concepts. Contrary to what many may think about Lee hogging credit for himself, this may not have been all of Stan’s doing as it most definitely was in the company’s best interest to have one of their employees recognized as creator of the line, rather than a freelancer who might someday leave and try to take some of the creations with him. With the general—and some of the comic bookreading— public believing all of these great ideas came from Stan, offers began to come his way. Artists and Directors were asking to work with him. Colleges were approaching him to lecture to aspiring students on how to create. Newspapers and magazines were asking him for interviews and articles. Stan was finally reaching the point where he realized that his newfound status might be the ticket out of comics and into the big time. As Stan courted his celebrity, he began to slowly relinquish his scripting chores on various Marvel titles one by one.

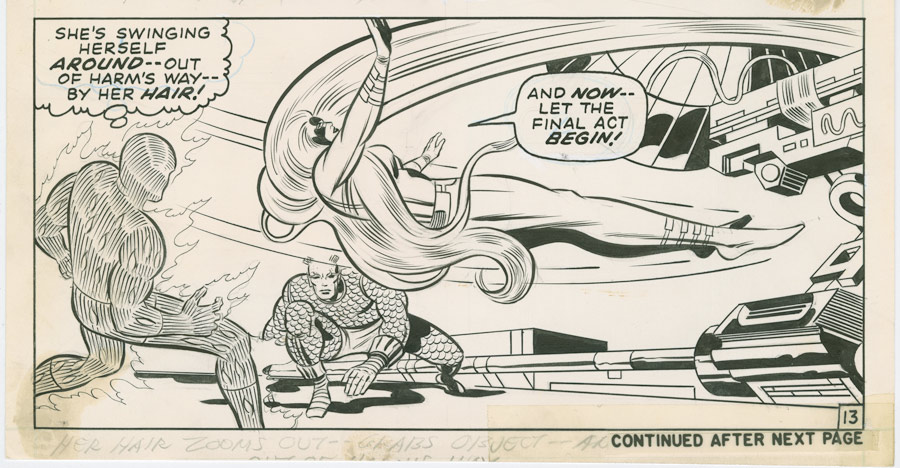

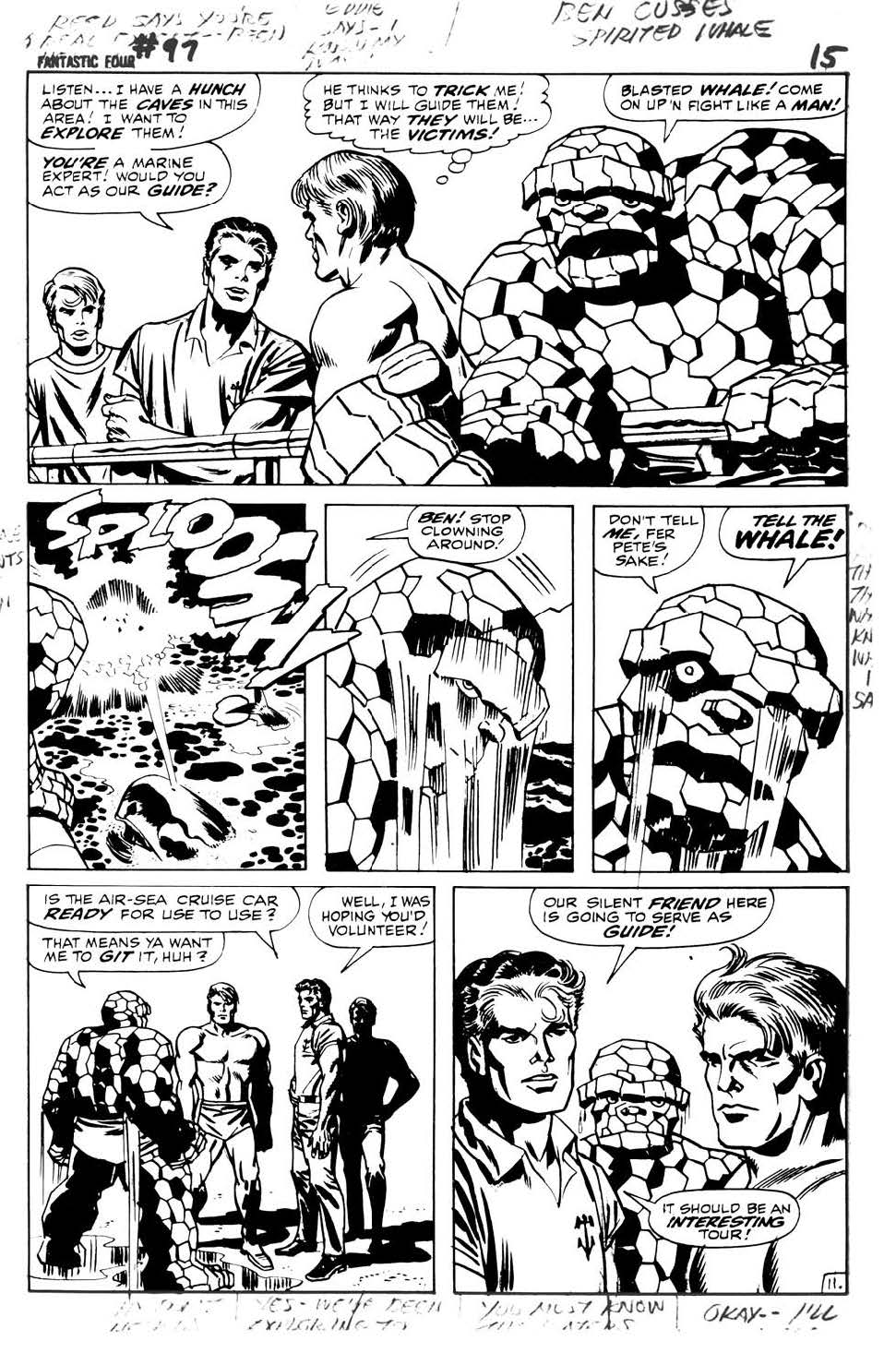

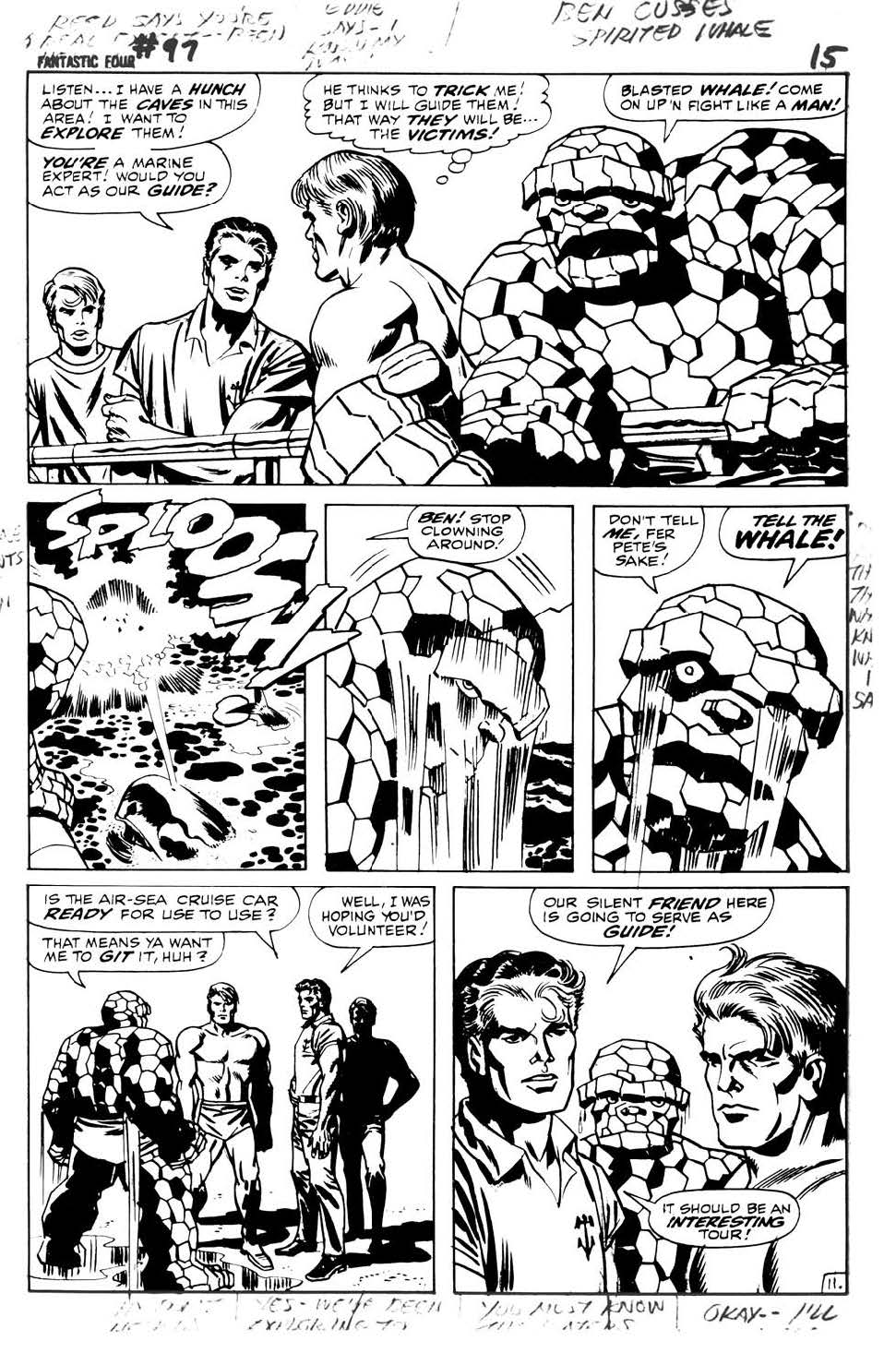

Jack’s margin notes from FF #97 (April 1970) show he intended the Lagoon Creature—Jack named him “Eddie”—to speak, but Stan ignored it.

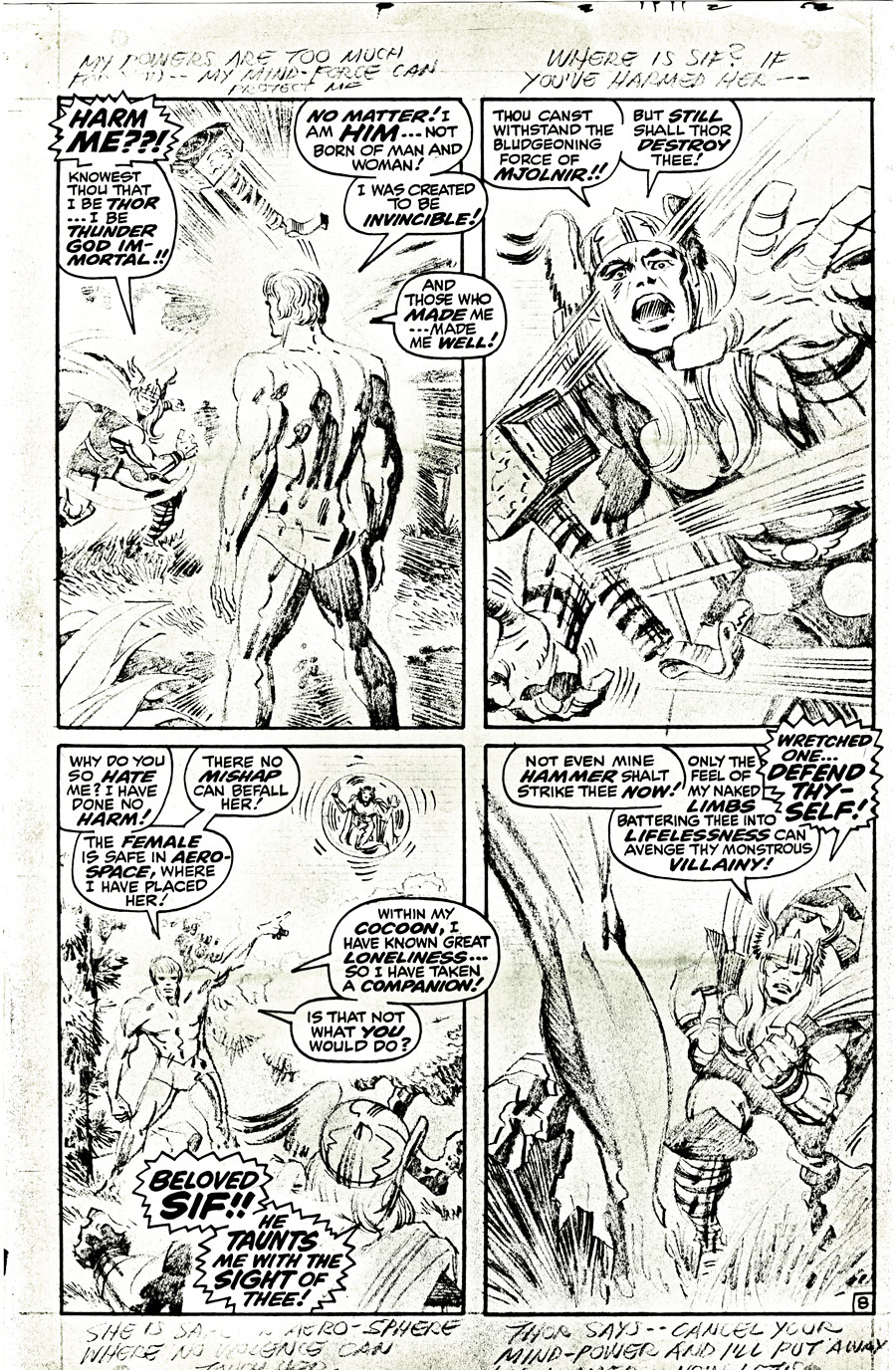

Shortly before the Marvel purchase by Perfect Film, the title line was expanded; the characters showcased in the “split” books—Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, and Strange Tales—were each given their own respective books, not to mention new titles being created like Captain Marvel, Captain Savage and Combat Kelly, and Not Brand Echh. Lee did the majority of the scripting (towards the end, some editing only) on the split books up until their transition, after which he left virtually all of them, handing the scripting reins over to guys like Roy Thomas, Gary Friedrich, Archie Goodwin, Arnold Drake, and others. He edited only, saving his scripting hand for Daredevil (which he left in March ’69), Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, Thor, and Captain America. Lee also had plans to script the upcoming Spider-Man b-&-w magazine, a mentioned Inhumans book, and of course the Silver Surfer. Of the five titles Lee was still scripting, Kirby was drawing three of them: FF, Cap and Thor. One wonders why Lee never relinquished scripting the titles on which he “collaborated” with Kirby. Some speculated that, since Jack was doing the lion’s share of the work on those books with little or no input from Lee, and all Stan had to do was dialogue and edit an already fleshed-out story, it was less work for him than with less experienced artists—but the longer they seemed to be working together, Jack grew more and more frustrated with Lee; their collaborations began to become more like grudging co-operations, with each man trying to put their own plotting into stories that were meant to be agreed upon. The new Surfer book was a particularly stinging slap in Jack’s face; since many believe that Jack could’ve asked for and gotten any title in the Marvel line to work on, and this title was not mentioned or offered to him, it was pretty obvious to him that he wasn’t wanted on it (or his take on the character, at least). Jack had mentioned to Lee his wanting a writing or at least a plotting credit, but getting Lee to give a writing credit to any artist was a difficult task (shockingly, Steranko, a virtual nobody at that time, somehow got Lee to acquiesce after doing only two issues worth of work—another slap in Jack’s face). Jack was situated in California by 1969, even more isolated from Marvel than he had been in previous years, with Stan only talking to him if he had to. The stories Jack worked on that last year for Thor and Fantastic Four (he left Cap in early ’69) were among the most mundane of his run—decent for any other artist, but downright common for Kirby. The lack of collaborating is pretty evident at this stage as there are myriad examples of Stan’s dialogue looking like it makes no sense whatsoever when coupled with Jack’s illustration. Fans thought he and Lee were slipping, but it wasn’t so much slipping on Jack’s part as it was waiting.

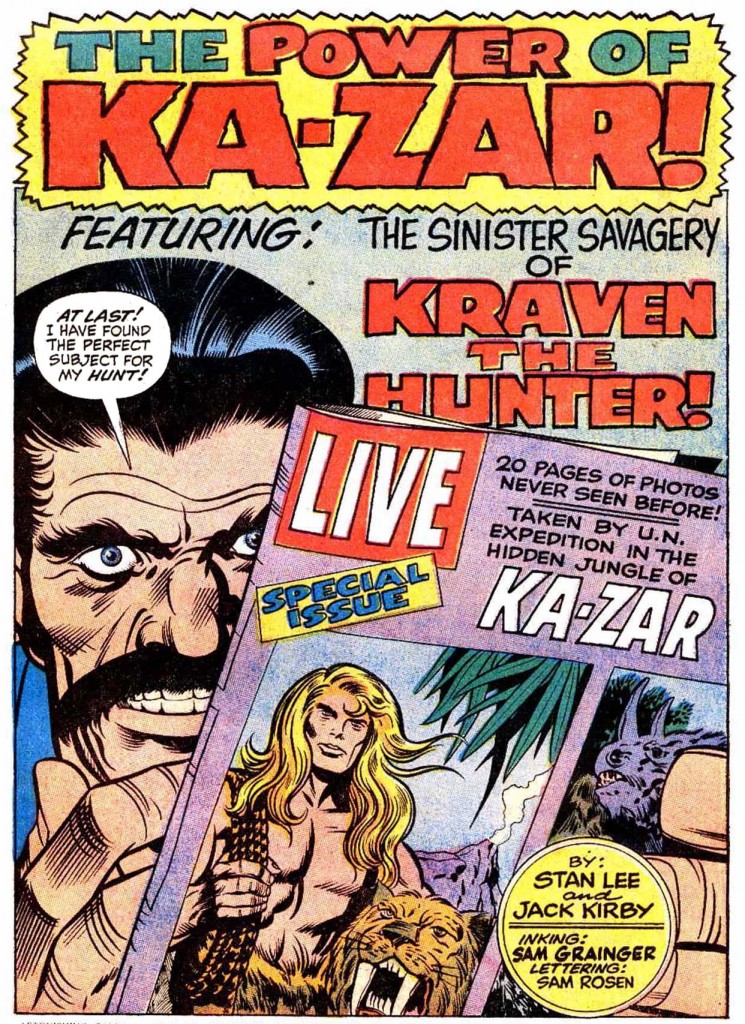

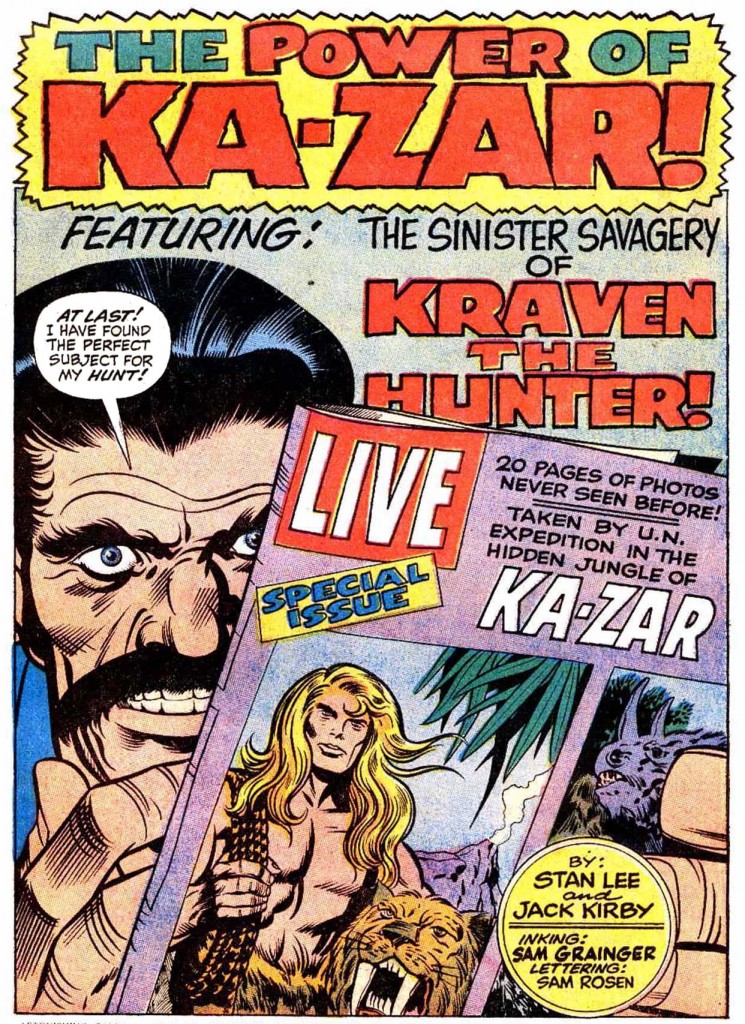

Splash page from Astonishing Tales #1 (August 1970).

During his last year on Thor, Jack seemed to be preoccupied with getting the origin of Galactus in print. He saw what Lee did to his Surfer and didn’t want the same fate to befall his other great cosmic creation. In FF he seems to have his final fun doing a gangster homage in his last four-part storyline. The rest of the year for the respective books feature retreads of old plots and old foes, and some new ones. Thor introduces Kronin Krask, the Crypto Man, and the Thermal Man; Fantastic Four came in with the Monacle and the Lagoon Creature. The fact that Goodman decreed that there be an end to continued stories for a while didn’t help the situation, as suspense and action then had to be crammed in or reduced. Although it wasn’t showing, Jack was arguably at his artistic height and these restrictions didn’t become so apparent until he left (once he got to DC, it’s almost like Jack’s art exploded out of these confines). Some speculate that towards the end of their association, these last new characters were probably from the plots that Kirby got from Lee, because it was reported that Jack was asking Stan to come up with the plots by this time; but upon reviewing original art from these stories, there is nothing to indicate any difference in the way they had always worked, so it’s entirely possible that Jack came up with them. Of the new characters introduced, only one—Agatha Harkness— would be utilized by Lee as a recurring character. By that time one would think that that was not Jack’s intention, however. It would be the last example of Stan using his editorial savvy to get something marketable out of one of Jack’s “throwaway” characters. Still working without a contract or any type of reassurance for job security, Jack was still doing work for Marvel, good work, but it wasn’t his best work. Some thought Jack was burning out; quite the contrary, he was just burning.

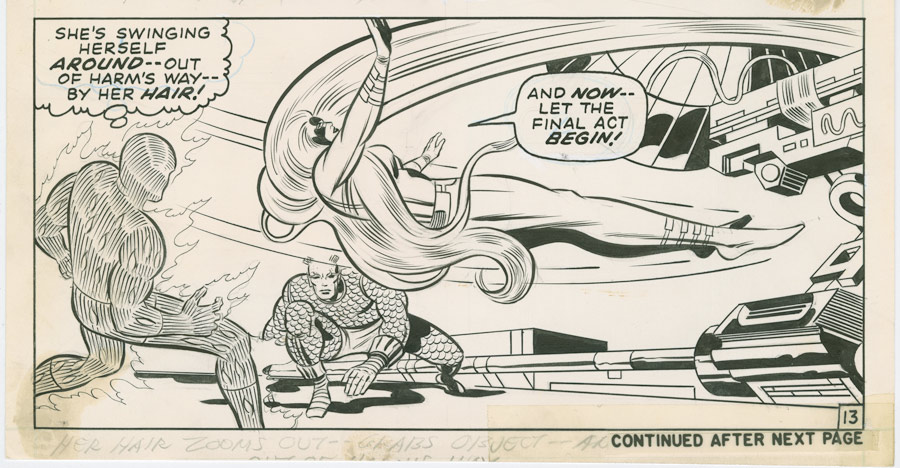

Final panels from Jack’s last issues of Fantastic Four (#102, Sept. 1970) and Thor (#179, August 1970), showing messages of war and hope.

While Marvel refused to talk to Jack, Carmine was ready to listen. He went to California to continue his quest to lure Kirby from the competition. The fact that Jack was on the West Coast meant little to either publisher, although it was unusual at that time for any comic book personnel to not work out of the New York area. Only an artist of Jack’s stature could get away with working clear across the country, working by phone and mail almost exclusively. Carmine asked Jack what would it take to get him for DC. Foremost in Jack’s mind was a contract that would ensure continued financial security, but he wasn’t about to leave out the “little things” that Marvel refused to give him: A writing credit (in fact to write his own books), editorial control (remembering what happened to the Surfer and Him—to name only two—Jack wasn’t going to see his creations stolen from him or twisted into something different ever again), and a percentage of any merchandising from any characters he created. This was a hefty request for its day, but Carmine wanted Kirby at DC; it would be the coup of his editorial career, but he had to get the OK from the new bosses. Leibowitz was “old school” and requests like these were usually shot down, just as they were by his contemporary Goodman, but there was one difference: Goodman promised and reneged, and to Jack that was not very nice!

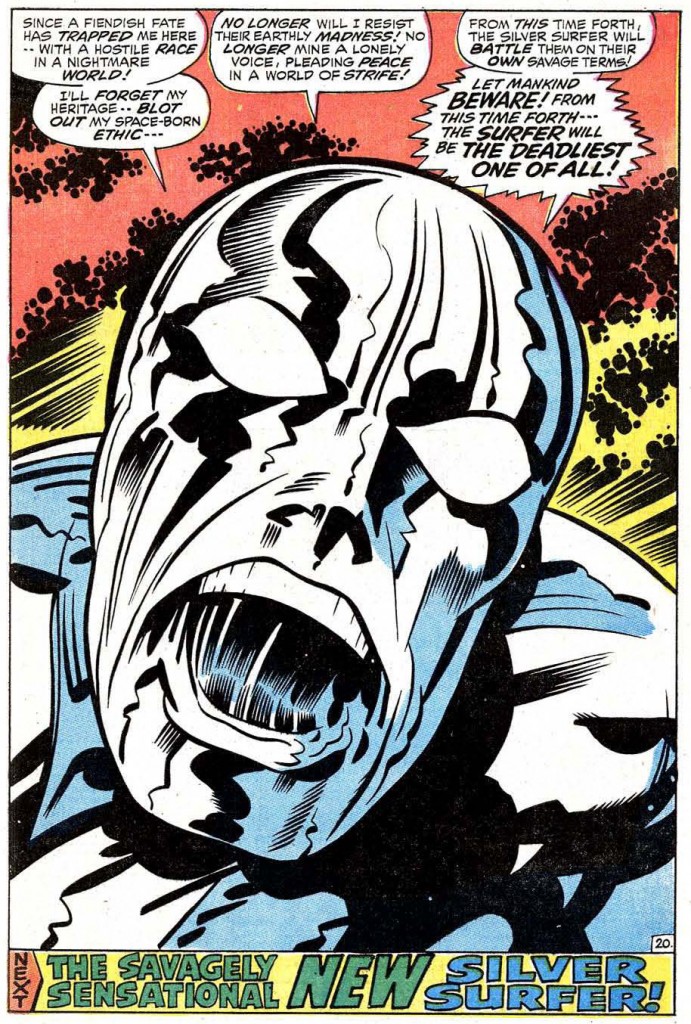

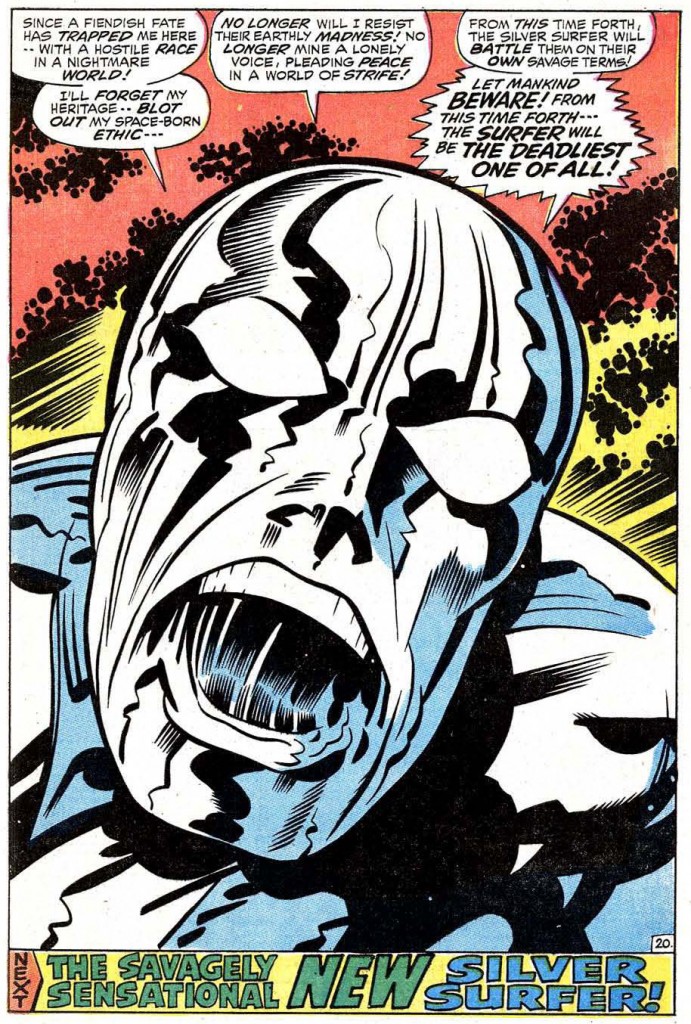

Final page from Silver Surfer #18, a book that must’ve been particularly galling for Jack to draw. Kirby was initially snubbed for the art chores on the book, and the series floundered for seventeen issues. Then Stan Lee called in Kirby to try to course-correct the book for inker Herb Trimpe to take over with #19, but the series was cancelled with this issue.

While negotiations continued, Jack got a few final surprises from Lee. Jack was asked to do the stories for the Inhumans in a new anthology (split) book, Amazing Adventures. The Inhumans was a book that originally Stan wanted Jack to put out years earlier, but it never made it to the schedule (some believe that the “Inhumans” back-up stories in Thor were the aforementioned book split-up, with other short “Inhumans” stories added until the back-ups were stopped completely). The surprise was that Jack would get a writing credit for the stories he did. Was this appeasement on Lee’s part, or was this the only way Stan could get Jack to do these stories (in which case, the surprise was on Stan)? Probably the former, as Stan could’ve simply gotten another artist for the book, but unlike the Surfer, Stan wanted Jack’s particular input on the characters he (Jack) created (in a 1968 fanzine, when asked directly, Jack states that he created the Inhumans). Jack also contributed “Ka-Zar” stories for Astonishing Tales, scripted by Roy Thomas, and did what would be the final story/issue for Lee’s failed Surfer comic. Kirby must have looked upon this particular job with mixed emotions to say the least (the last page says it all). The Fantastic Four’s one-hundredth issue, alleged to have been scheduled as a giant-sized story, was truncated to a miserable nineteen pages, a sad epitaph for one of Jack’s greatest series. Reportedly Jack finally got those plots he asked Lee for, in the last couple of FF stories. Jack continued to grind ’em out but, with the return of Infantino, Jack would now, finally (with Marvel anyway), grind to a halt. Jack’s requests were acceptable and it was time to sign. Up to the last minute, Jack waited, hoping he could come to some agreement with Goodman and the new owners at Marvel, but he was just another artist to them. Stan knew his worth, but also knew he wasn’t going to go to bat for him. He was worried enough about his own future with the company, and thought Jack was just disgruntled over the credits and some of the stories; he’d get over it. He was wrong!

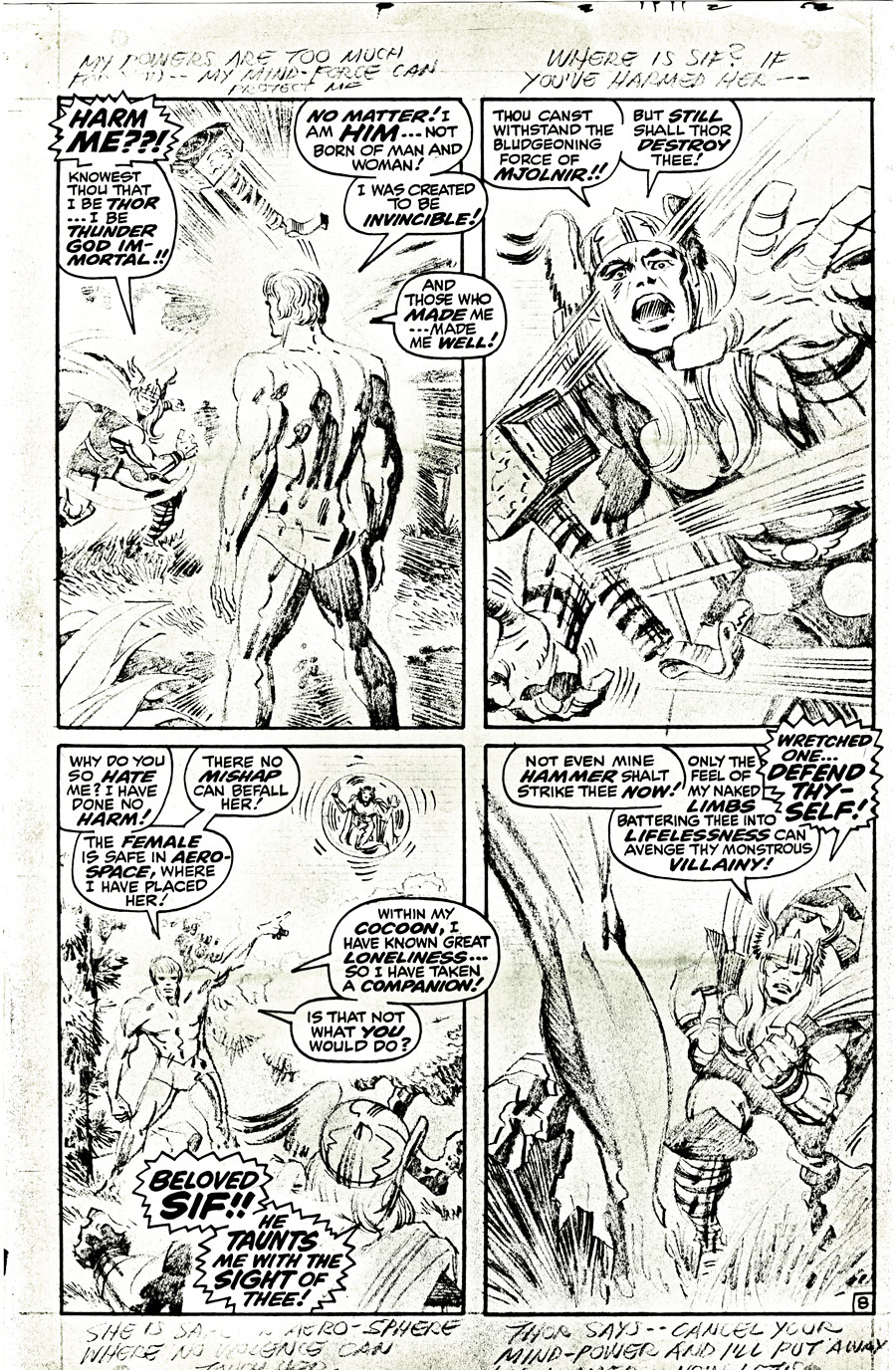

Pencils from Thor #166 (July 1969), featuring “Him”; like the Silver Surfer, he was another character Jack felt was changed from the direction he had planned for the character.

The day Jack signed his contract with DC he called Stan and told him he had his last work for Marvel. Stan was indeed surprised for, although he knew Jack was unhappy, he never thought he’d leave. The last Thor and FF stories Jack worked on had themes of hope and war in the respective last panels; one can only wonder about the irony of it all.

What happened after Jack left has been discussed by many. Kirby was gone but sales continued to rise; was it because the new creative teams produced better stories? Hardly! Sales continued to rise on Spider-Man after Ditko left in ’66 also; sales continued to rise on almost all the Marvel books. Stories had little to do with it; it was impetus fueled by Marvel fanatics if anything.

Lee went on without Jack for approximately two years. He stopped scripting Thor one year after Jack’s departure, and finally stopped scripting Spider- Man and Fantastic Four a year after that. Stan went on to become publisher, then president of Marvel, publishing book after book on the Marvel heroes based on his “crazy ideas.” It’s reported that the copies of these books that Jack had were edited by Kirby with a pair of scissors, cutting out falsities, thereby reducing many pages to Swiss cheese. Once at a convention, a fan asked Jack if he’d sign one of the Lee books. Seeing that Lee already signed it, Jack said to the fan that he’d sign his name in ratio to his contributions as opposed to Lee’s; Jack’s signature was five times larger.

Kronin Krask, one of the forgettable villains that populated Kirby’s books his last year at Marvel. Was he Jack’s idea or Stan’s? This page is from Thor #172 (Jan. 1970).

To this day Lee credits his artists as the most creative people he ever worked with; what they created, however, you rarely hear from Stan. As recently as his new autobiography, Stan continues to relate how Marvel came about, always using the collective “we.” He’ll graciously acknowledge the likes of Kirby and Ditko as two of the best artists he ever worked with, but according to Stan, the “ideas” came from him; they only fleshed them out. (At this point I’d recommend subscribing to Robin Snyder’s The Comics where Steve Ditko is giving his side to the Lee/Ditko “collaborations.”) As far as any problems with Jack, in a recently released DVD with Kevin Smith, all Stan can relate is that Jack was unhappy about some form Marvel wanted him to sign to get his originals back (this happened with Jack in the mid-’80s). For some reason Stan believes Jack blamed him for this problem (Jack didn’t), and that’s all Stan would say about any problems with Kirby—no mention of why Jack left Marvel.

In a 1977 interview, when asked why he embellishes his answers to the point of not really giving the answer, Stan responded in so many words that the public wasn’t interested in boring tales, even if they were the truth. Since he admired Shakespeare so, I think that the best line that suits Stan would be from Measure for Measure: “It oft falls out, To have what we would have, We speak not what we mean.” So the greatest team in the Silver Age of comics was no more. Jack’s heart left Marvel long before his person; a long last year that stretched out over several. In later years, Jack cited why he felt he had to leave, but just as with Ditko (and Wood for that matter), Stan will tell you how he doesn’t know why Jack left. He knew Jack was unhappy, he knew Jack was working with no contract, he knew Goodman reneged on promises made; but he doesn’t know why Jack left. It seemed any artist who contributed significantly to the creation of the Marvel super-heroes had a failure to communicate and eventual falling-out with Lee, but he doesn’t know why!

How could he not know?

While Jack filled in for John Buscema on Silver Surfer #18, Big John took a stab at Thor in issue #178 (July 1970). After Kirby left, Neal Adams drew two issues, and then Buscema became the series’ regular artist.