A quick pointer to Susan Myrland’s interview with Dr. Molotiu

Monthly Archives: July 2012

An Inference of Influence

A Failure to Communicate – Interlude

Thanks to Mike Gartland and John Morrow, The Kirby Effect is offering Mike’s “A Failure To Communicate” series from The Jack Kirby Collector. Captions on the illustrations are written by John Morrow. – Rand

Interlude was first published in TwoMorrows’ April 2000 Jack Kirby Collector 28.

While others write about Kirby’s influence in this issue, I’d like to discuss some of the contributions of the one professional who influenced Kirby in a myriad of ways, and quite arguably brought him towards his greatest recognition: Stan Lee.

Well, think about it; although Stan may not have been an influence to Jack in the artistic or storytelling sense, his effect on Kirby’s work at Marvel, for good or bad, is present in virtually every issue of every title Jack worked on. The majority of the effects were obviously good, as reflected in the love we share for their combined work.

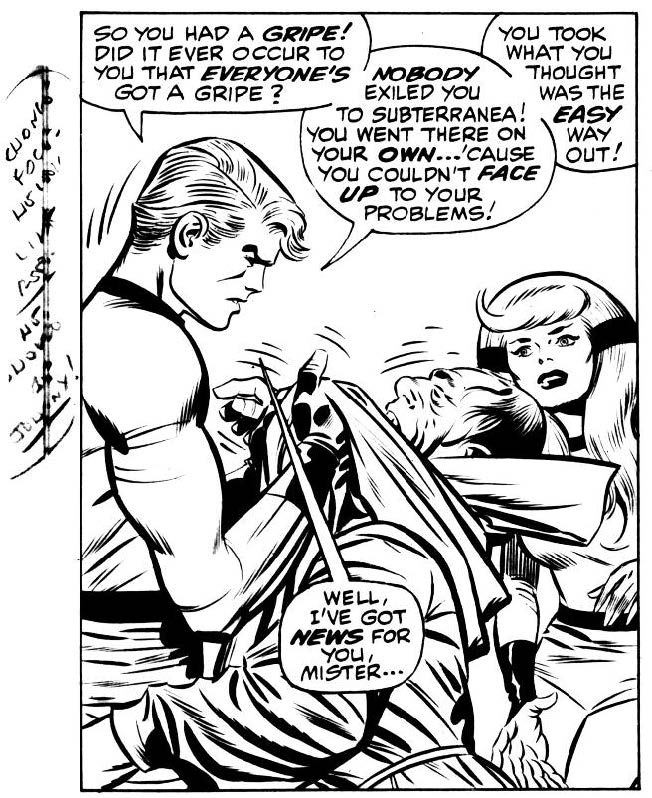

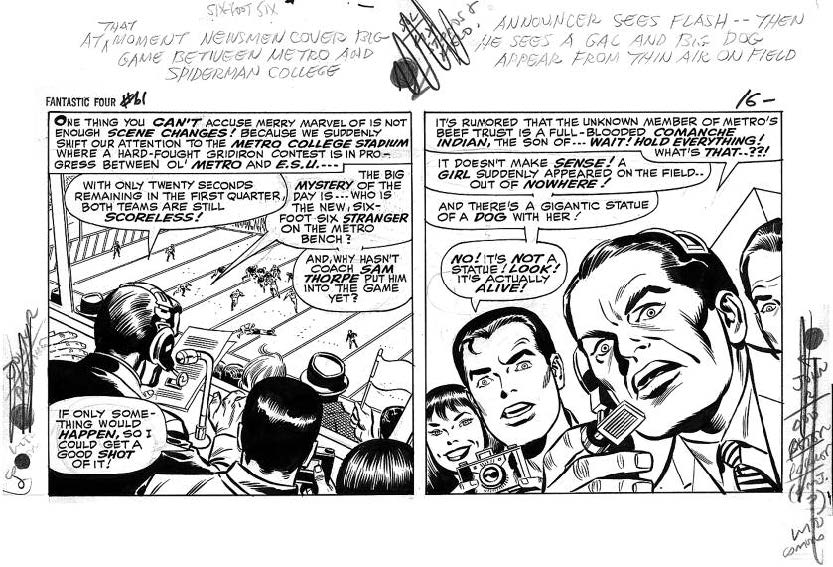

A good catch (and a little venting of frustration) by Stan on this FF #90 page. His notes to Sol Brodsky about the way Jack drew Alicia’s eyes: “Fix Alicia’s pupils, Sol — She’s blind! If only J.K. were consistent.”

Although many throughout fandom speculate that Jack was the concept or “ideas” man behind the “House of Ideas,” it must be noted, however true, that Stan was the one asking for those concepts and ideas, especially during those critical early years. Stan is therefore rightly recognized as the father of the Marvel Universe, being a seminal influence behind not only Jack, but all areas of production. Stan was a creative midwife, periodically provoking Jack to bear down and push. This is not to say that Stan didn’t have ideas of his own, but one of his strengths was knowing how to utilize the creative talents of others. Stan’s input into the creation of Marvel’s earliest and most famous characters should not be disputed.

When Goodman wanted to start up a super-hero line again, he went to Lee and Lee went to Kirby—not anyone else at Marvel— to come up with a book. Many cite the similarities between the FF and Jack’s Challengers and use this hypothesis to say that most of the idea for the FF came from Jack, but Lee’s influence is obvious from the two most colorful characters, the Torch and the Thing. It’s a pretty safe bet to assume that Stan would want a monster-like character, in keeping with the then-popular line of monster-related books that they were putting out. The inclusion of the Torch was definitely Lee’s input; it was all Jack could do to keep Stan from bringing back other Golden Age heroes for that book, and convince him to go with new characters. Stan still showed his love of the old guard by reviving the Sub-Mariner, and giving the “new” Torch his own title as soon as he could.

Bringing back old characters was not to Stan’s detriment; if not for him, we of the Baby Boomers would never have enjoyed the likes of the Torch, Namor, or ironically Cap. Jack, being progressively creative, almost certainly wouldn’t have gone into the past and saved these great characters. Thanks to Stan reviving him, Captain America is more popular and recognized today than he ever would’ve been had he remained buried among the WWII relics. Also thanks to his reprinting of Golden Age stories early on, Stan became the first to re-introduce a new generation to the works of Simon & Kirby, Carl Burgos, and especially Bill Everett.

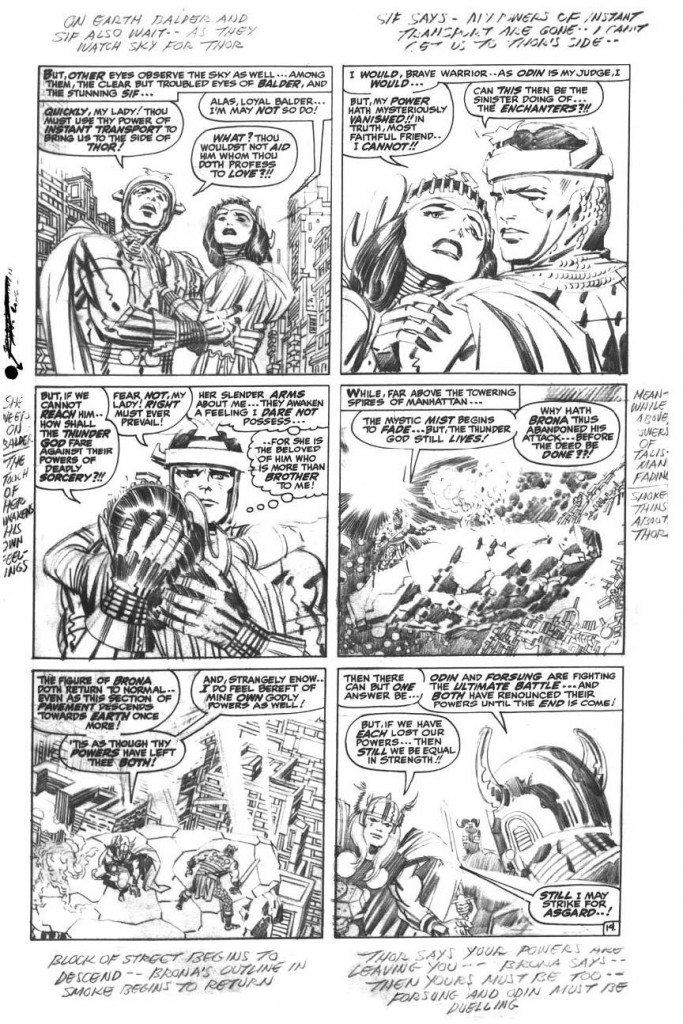

Page 14 pencils from Thor #144. It appears Jack came up with the somewhat out-of-character subplot of Balder being secretly in love with Sif. Stan went along with it for that issue, but wisely never followed up on it.

The Hulk, Thor, and Spider-Man were the next triumvirate that Kirby came to co-develop when Stan asked Jack for ideas. As with the Thing, Stan most likely asked for a character like the Hulk. In earlier pre-hero Marvel stories, every now and then a monster would make a re-appearance, perhaps in response to fans or positive sales. Based on this, Stan may have wanted to try a series with the same monster in the lead; but maybe it came too late. The Hulk was pretty obvious as far as a monster tie-in was concerned, and maybe this was one of the reasons that initially, he didn’t succeed. There were a lot of monster stories already ingested by Marvel readers and, compared to books like FF and Thor, the Hulk was just another monster, not super-hero, book. Thor was discussed previously; Jack’s love of mythology fed this title for years, with Stan’s humanistic take on gods giving it the vitality to keep going.

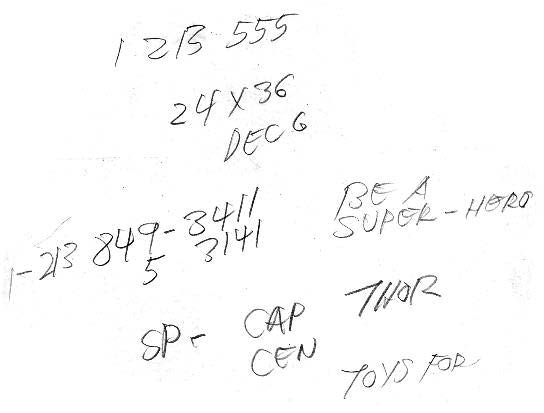

Jack jotted this down on the back of one of his statted pages from FF #46. Was it a note taken during a phone plotting session with Stan, or Jack’s own idea for a subplot?

Ironically it is Spider-Man, Jack’s failed concept, that becomes Stan’s magnum opus and Marvel’s greatest success. Spider-Man, more than any other character, is a testament to the control that Stan had in the development of Marvel’s heroes. Stan may not have developed these characters artistically, but he knew what he wanted, and none of them would exist as they do today if not for his influence and input. And no, I didn’t forget Ant-Man, but he also was discussed in a previous issue; I also didn’t forget that one should never mention the development of Spider-Man without acknowledging the immense input and talent of Steve Ditko. (As an interesting footnote, the rejected Spider-Man origin, where a kid finds an object that gives him his powers, may have been re-vamped and used in the origin for Thor, showing how close in time these two characters were being developed by Jack & Stan.)

As reported in the letter column of TJKC 27, Jack’s handwritten dialogue is visible in the balloons (not the margins) of the original art from Strange Tales #103, leaving the question of whether Kirby, Lee, or Lieber wrote the original dialogue for this story.

You would not have seen FF #12 or Spider-Man #1 as they exist today if not for Stan. Well, so what, you ask? The same could be said for any Marvel issue at that time. What I’m trying to point out here is not only Stan’s influence on the finished product, but the initialization of cross-marketing the characters between titles. This laid down the basis for a definitive point of reference between the characters’ individual plots in their own titles, interwoven occasionally with the other books, backed up with references in current books to previously published “back issue” stories; thus establishing a “timeline” that all of the super-hero books followed. All of this is known today as “continuity.” Stan established it, it tied the Marvel Universe together, it was wonderful, and boy, does the current Marvel ever need it today.

Stan was able to maintain all of this continuity because he not only plotted and wrote some of the various stories, but was editor as well. Unlike DC’s method of several editors to oversee their titles, Stan was the sole editor for anything produced at Marvel. He was able to stay on top of the expanse of titles due to his acceptance of the “Marvel method” of writing, whereby the artist became a collaborator in the development of the story. This method of writing was established when Kirby returned Marvel in the late ’50s, but was cemented in as the recognized standard procedure once the super-hero line became established, and due to the adaptability of the other talented artists at Marvel at that time—namely Ayers, Ditko, and Heck. Thanks to the Marvel method and an assist in scripting from his brother Larry, Stan was free of the tedious and lengthy task of writing full scripts, while at the same time allowing his staff to interject fresh ideas into sometimes timeworn plots.

Another example of Stan’s important influence as an editor: This panel from FF #89 features a Romita face on the Human Torch. The reason is clear from Stan’s note: “Change face–he looks like Reed–he should be Johnny!”

The Marvel method became a proving ground for artists seeking a new approach to their work. Some could or would not work this way; others adapted readily and are recognized today as the unsung storytellers at Marvel. After Stan’s “fantastic four” of Kirby, Ditko, Ayers, and Heck, artists like Romita, Buscema, Sinnott, Severin, Everett, Colan, Roth, Tuska, and Trimpe became stalwarts to Marvel fans everywhere. Along with editing plots, scripts, and dialogue, Stan edited the art as well. For someone who wasn’t an artist, he became respected by many who were for his acumen on how to render a story for the greatest impact on the reader. A big tip of the hat must be given to Sol Brodsky as well, who handled many of the production and editing assignments when Stan became swamped; truly a man who deserves more recognition than he receives.

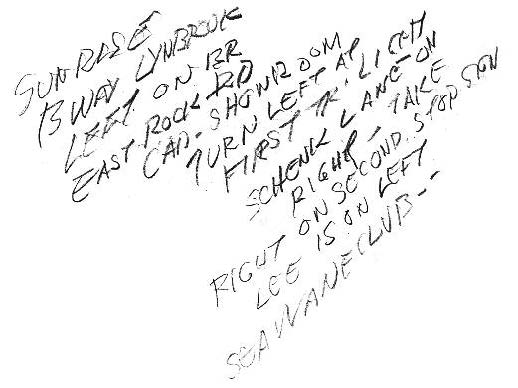

Holy Marvel Minutiae! The back of another FF #46 stat shows Kirby’s handwritten directions to what looks to be a lunch meeting with Stan. Does anyone know if the Sewane Club still exists?

This leads to another of Stan’s attributes: Rather than a company of seasoned professionals who dealt with their patrons accordingly, Lee acknowledged that Marvel was a “nuthouse,” filled with zanies doing their darndest to satisfy you, the fan, and enticing you to be a part of it. To this extent he debuted “the Bullpen,” a bunch of flawed humanity that was usually making mistakes, generally having a good time, and always open to suggestion. Stan, in listing credits and establishing a page devoted to the goings-on at the Bullpen, introduced the reader to virtually everyone who worked at Marvel at one time or another. Even the office workers and staff were mentioned in the books; to this day fans seek out Flo Steinberg. Readers might never have known that draftsmen like John Severin, Paul Reinman, Chic Stone, George Roussos, and Joe Sinnott worked at Marvel had Stan not given a credit line to inkers, something never done on a regular basis anywhere; and giving credit to letterers was unheard of, but what Silver Age Marvel fan doesn’t know who Artie Simek or Sam Rosen were? As a matter of fact, some of Stan’s funniest writings were at his letterers’ expense. Stan would generally have the letterer be the butt of an alliterative list of quips, after introducing himself, the artist, and the inker; and what gives the humor an ironic twist is that the letterer would be forced to letter in the quip. It was all in good fun.

Now before you go writing off your letters about these things existing in previous companies like Fawcett, EC, or DC, I’m not saying that Stan was the first to do such things, but to his credit he did them in such a way, and expanded upon them to such an extent, that fans everywhere attribute continuity, letters pages, a bullpen, credits, and crossovers to Marvel.

Stan even paid close attention to lettering. This FF #89 panel includes STan’s note to Sol Brodsky: “Lettering too stiff–Get some black dots and stuff in… (rest is illegible).”

This is perhaps Stan’s greatest talent: To take something done previously and give it his own twist, thereby enlivening it to appear fresh and innovative. Stan was vitality incarnate; this permeated each and every book. He showed it to you, made you believe in it, and want to share in it. Stan gleaned the best from other publishers and through irreverence and humor, made you think that it could only come from Marvel.

But what, do you ask, was his influence on Kirby? Simply put, Stan was both the ignition and brakes to the creative engine that was Jack Kirby. Stan could both feed ideas to, and take plots from Jack, turn Jack loose and then clean up the excess, saving what was needed for publication. If there was too much good material in one story, Stan would have Jack stretch it out or save it for future use. Kirby’s creativity had to be properly controlled or his plots, concepts, and characters would run roughshod over each other, becoming jumbled, smothered, or forgotten. Jack needed a strong editor, which is why many cite his best work as coming from his relationships with Stan and Joe Simon. Although Jack’s Fourth World storylines are excellent in their conception and design, it would’ve flowed better had he employed such an editor, in my opinion. Stan managed to keep Jack’s stories from becoming disconcerting.

Jack appears to be jotting down notes for his Toys For Tots poster during a phone call with Stan. This was on the back of stats from Thor #152.

That last word can be used in that context, but that brings me to another of Stan’s talents: A word that you don’t see everyday, or may have to look up; the use of words, the turning of a phrase, the allocation of alliteration; in short, this guy could write. No one before or since has ever dialogued comics like Stan. His use of colorful, melodramatic flowing phrase sent fans by the ton scurrying for their dictionaries and thesauruses; and I’m not only talking about ten-year-olds, but college kids as well. How many of us were indirectly introduced to the great writers of yesteryear because, unknown to us, Stan would paraphrase their works into his stories; remember “Oh Wasp, Where Is Thy Sting?” (Tales To Astonish #69)? What a catchy title; camp, but catchy; but I notice it still sticks in my brain after 30+ years.

These panels from FF #61 show numerous Lee notes for corrections, particularly to John Romita to redraw Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson. Stan was extremely influential in maintaining a consistent look for the characters.

But camp was what the Sixties comics were all about, and Stan rode the crest till the end. He kept a keen eye on what was topical and never lost contact with the fans. He found out what was “in” and utilized it to sell the books; remember Marvel “Pop-Art” Productions? Although it was one of Stan’s attempts that didn’t catch on, he was always trying new venues and never stopped. He knew how to sell the product without looking like a corporate employee. Stan was hip, he was in; and this is why he is looked upon today by so many fans with reverence and respect. Stan grew up with us, was one of the first adults that seemed to understand us kids; he treated us with respect, made us feel like we were a part of something cool and happening. He is as much a beloved cultural icon to us as Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, Mickey Mantle, or Aurora models. The fortunate thing for us though, is that Stan’s still here, still fabricating, still bombastic, still alliterative, still humorous, still controversial, still Stan.

In case you missed it… a new Kirby Kinetics post from Norris Burroughs

One of the personal blogs that the Kirby Museum features is Kirby Kinetics, where Norris Burroughs offers monthly analyses of Kirby’s art.

This month: a second entry regarding Kirby’s spacial relationships.

Submitted For Your Approval…

A Failure To Communicate – Part Five

Thanks to Mike Gartland and John Morrow, The Kirby Effect is offering Mike’s “A Failure To Communicate” series from The Jack Kirby Collector. Captions on the illustrations are written by John Morrow. – Rand

Part Five was first published in TwoMorrows’ November 1999 Jack Kirby Collector 26.

There’s been some response during the course of my writing the “Failure to Communicate” articles that I was being unfair to Stan Lee. Several people have written to TJKC expressing their disappointment in our trying to take credit away from Stan, reminding us of Lee’s contributions, his superior writing skills (comparing it with Jack’s solo work yet again) etc., and citing that, just because Jack left a few border notes, it doesn’t necessarily mean he had anything to do with writing the stories—he was in on the plotting, but Lee was the writer. And of course there’s the old favorite critique of every research writer: “You don’t know because you weren’t there.” (By the way, there was a much larger percentage of letters approving of the articles, for which we say “thanks.”)

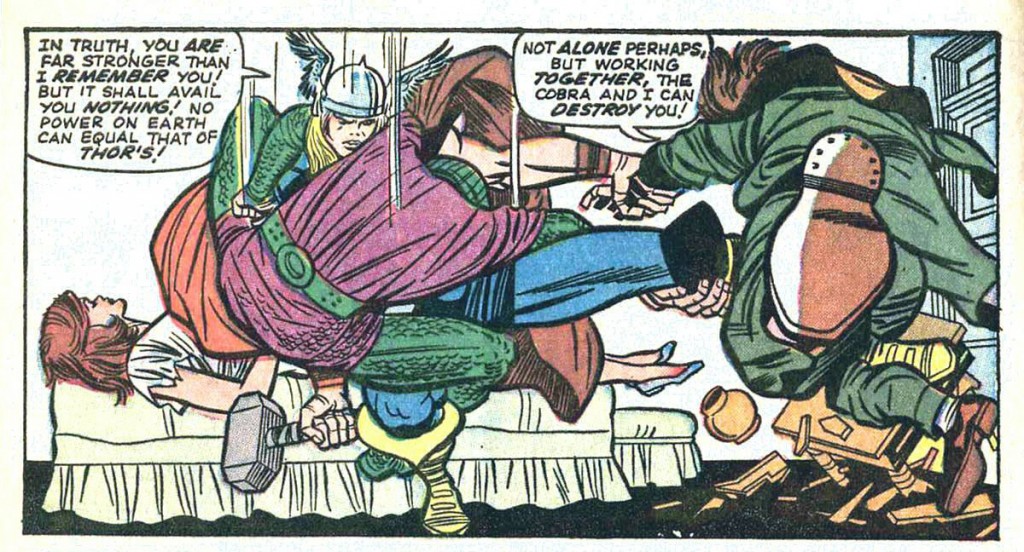

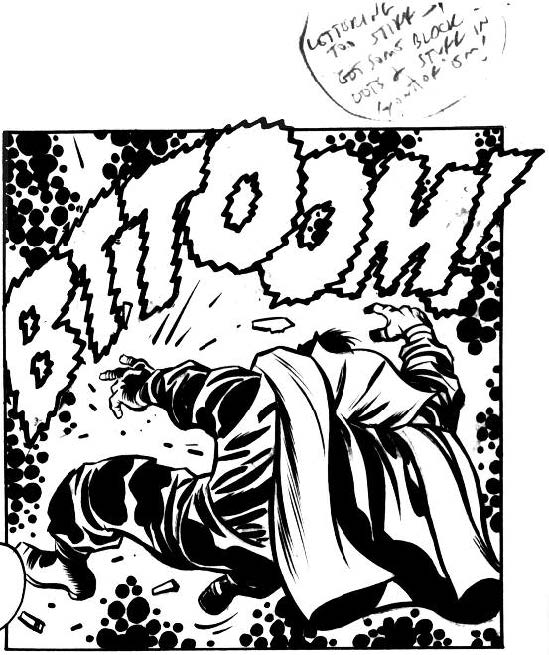

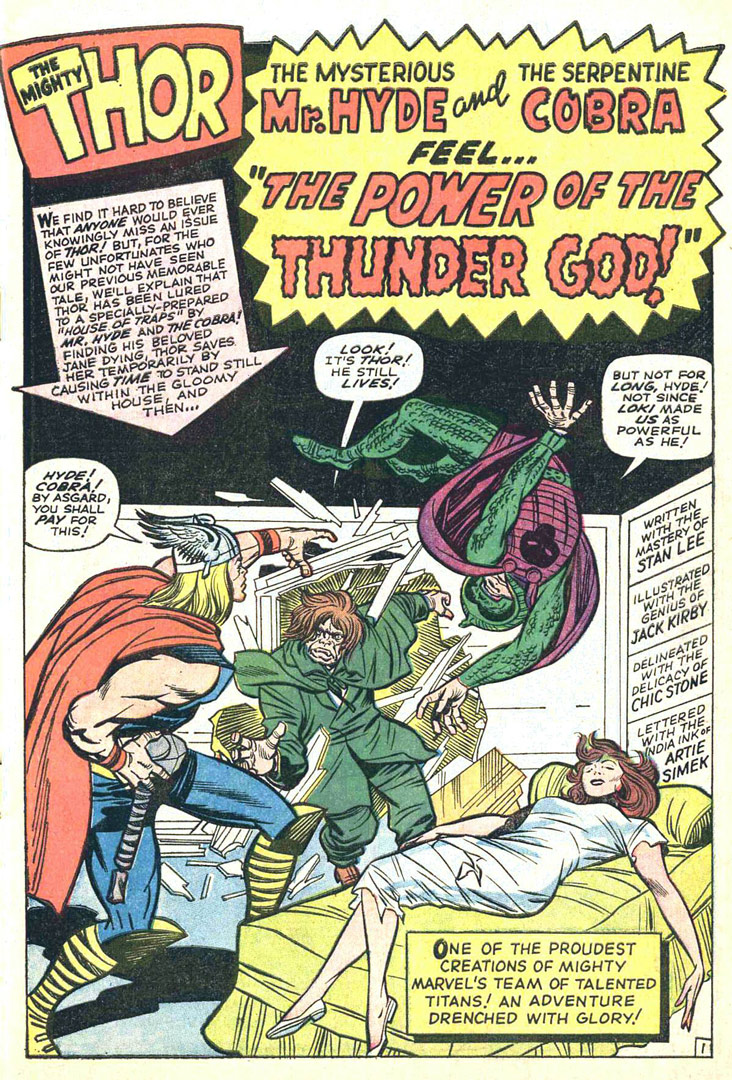

Splash page from Journey Into Mystery #111 (Dec. 1964):

Cobra’s lower arm was erased and re-positioned.

Rather than going into a lengthy explanation concerning my opinions of the Kirby/Lee creative process, I thought it would be far more enlightening and entertaining to let the stories try and speak for themselves; thereby giving the reader an example of how a typical Kirby/Lee plot was finalized before printing. In the next few articles I will be showcasing Kirby/Lee stories from various books that they have worked on, the stories to be determined by what original complete stories I can find; I will document whatever is on the original art and print it verbatim for the reader to see. It should not only give us a glimpse into the creative process of a Marvel comic, but reveal the seldom-seen editorial changes made by Stan (and of course, whatever notes Jack left for assist).

Page four, panel two: One of many panels that were used in the limited animation Gantray-Lawrence Marvel cartoons of the 1960s.

In keeping with the theme of this issue, I decided to start with a Thor story from 1964. Whereas some will attest that the Thor stories from 1966-on were pretty much Kirby directing the storylines, this story comes from a time when many believe that Jack and Stan were plotting together, or Stan was creating the plots solo. The story is from Journey into Mystery #111, the second half of a two-parter. The synopsis is: In the previous issue, Loki had increased the power of two of Thor’s arch-enemies, The Cobra and Mr. Hyde. Loki also reveals to them that, in abducting the nurse Jane Foster, they will gain the advantage over Thor. They kidnap her and take her to a specially-prepared house of traps; when Thor arrives and begins battling, Jane becomes mortally wounded. Thor suspends time around the house in order to keep her from dying; with her safe for the time being, he turns to confront his adversaries….

Below are the border notes left by Jack, broken down panel-by-panel; some have been cropped off by the printer, some have been rubbed off from handling. Also, any changes made by Stan will be revealed. Notes followed by a “X” mean that the rest was cut off or not legible. Where no panels are mentioned, no notes exist or were legible. Grab your copy of JIM #111 and enjoy!

(NOTE: This story was approved by the Comics Code Authority on 7/13/64, which puts Jack drawing it in June 1964. Throughout the book, Chic Stone’s bold thick ink brush lines are actually greyish on the originals; the faces stand out as denser black because they were apparently inked separately with a pen.)

PAGE 1:

Splash: Thor battling Cobra and Hyde X (Note: Cobra’s right arm was erased and re-positioned.)

PAGE 2:

Panel 1: Cobra and Hyde twice as powerful as they used to be (My note: Thor has two right hands)

Panel 3: With these tactics Thor X

Panel 4: Thor causes wind to blow X (Note: In word balloon, the phrase “—lash out with savage fury” was originally different; only the word “villain” can be made out beneath)

PAGE 3:

Panel 1: Thor grabs girl and bolts down corridor.

Panel 2: Traps spring up everywhere.

Panel 5: Hammer strikes invisible beam X

Panel 6: Heavy concrete block comes X

PAGE 4:

Panel 1: Room has been cleared of danger–Thor makes girl comfortable

Panel 2: Thinks situation over

Panel 4: X caution X

Panel 5: Rock tossed in remains X

Panel 6: Odin watches X

PAGE 5:

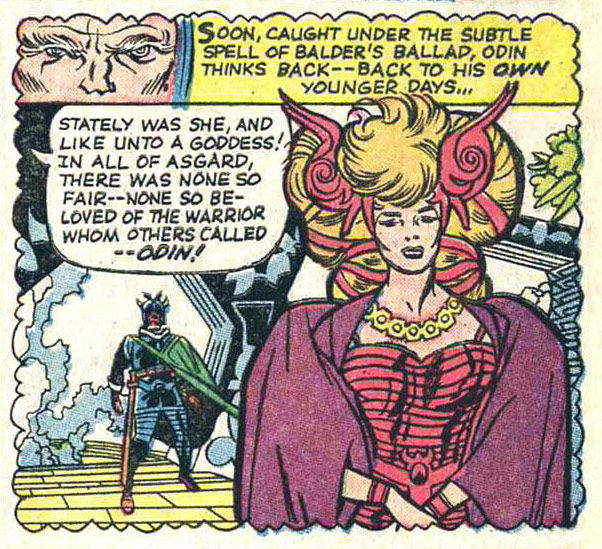

Panel 1: Notices how hard Thor battles for girl’s life—Balder offering to soothe Odin with song

Panel 3: X thinks back X

Panel 4: Thinks of gorgeous goddess–Thor’s mother

Panel 5: Loki breaks in X

PAGE 6:

Panel 1: Meanwhile Thor comes out to mop up villains

Panel 2: Cobra is too fast–Hyde is closing in

Panel 4: Thor wants to take on the better one first

Panel 5: Both think they are more X

Panel 6: Hyde grabs cobra–ME X

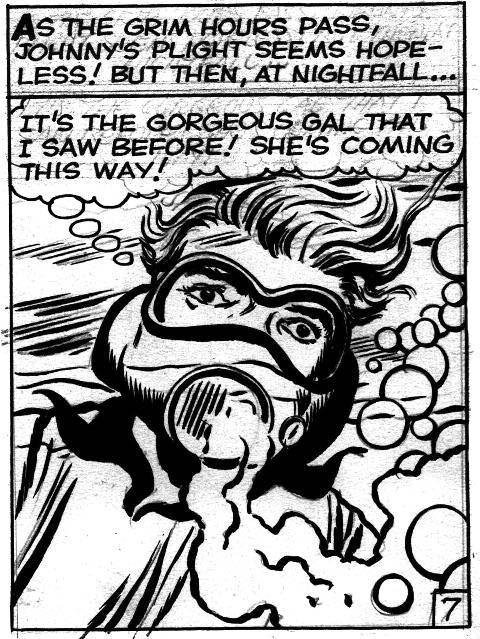

PAGE 7:

Panel 1: Cobra doesn’t like his attitude

Panel 2: Hurls Hyde

Panel 3: Thor X him back

Panel 4: Cobra hurls X

Panel 5: Thor’s hammer X

PAGE 8:

Panel 1: Cobra leaps like crazy but missiles catch up with him

Panel 2: He leaps up vent as missiles blow into gas

Panel 3: Meanwhile Hyde attacks Thor

Panel 4: Gas reaches Hyde X

Panel 5: Hyde smashes thru corridor X

Panel 6: Thor throws hammer X

PAGE 9:

Panel 1: Meanwhile Odin decides to help girl

Panel 2: Gives message to Loki to deliver to healer who lives beyond badlands

Panel 4: Don’t trust X you rat X I’ll take message

Panel 5: Balder rides off across badlands

Panel 6: He’ll never make it–Thor’s girl will die

PAGE 10:

Panel 1: Badlands get rough–One slip and into flaming lake (Note: the word balloon in this panel was originally the word balloon in the next panel, but Stan moved it over)

Panel 2: More danger–Balder sees something that makes him draw sword

Panel 3: Thor pursues Hyde X

Panel 4: Hyde turns on Thor

Panel 5: Meanwhile pushes X

PAGE 11:

Panel 1: Thor flips Hyde into ray (Note: Stan’s original caption for this panel read: “Meanwhile back on Earth, Thor’s own battle continues without let-up”)

Panel 2: Hyde stiff as a board (Note: in upper corner is notation “Chic Stone—ST-3-1899”)

Panel 3: Thor props him up X now just X

Panel 4: Slams wall to expose X

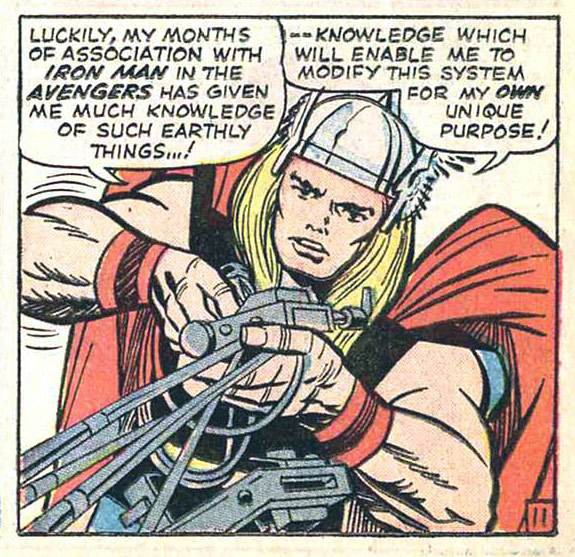

Panel 5: Association with Iron Man X

Panel 6: Rewires circuits to X

PAGE 12:

Panel 1: Restores wiring

Panel 2: High tingly effect courses thru circuits of entire house

Panel 3: Cobra, still slithering thru interior is reached byjazzed up effect

Panel 4: Cobra X duress X stop

Panel 5: Comes out X (Note: Stan changes the word “help” in balloon to “Hyde”)

Panel 6: Too weak to escape X

Panel 7: Cobra and Hyde ready for X (Note: the name Hyde in word balloon was originally something else, but cannot be made out)

Page thirteen, panel two; as proof of Thor’s love for her, Jack would’ve had him stay with Jane in the time warp for all eternity rather than have her die.

PAGE 13:

Panel 1: She’s still in bad shape, but house is in time warp so she’s still alive

Panel 2: If Thor lifts time warp she will die–They may have to stay together in time warp for all eternity together

Panel 3: X his touch is death X

Panel 4: Phantom is creature of a X

Panel 5: So Balder makes his sword X

PAGE 14:

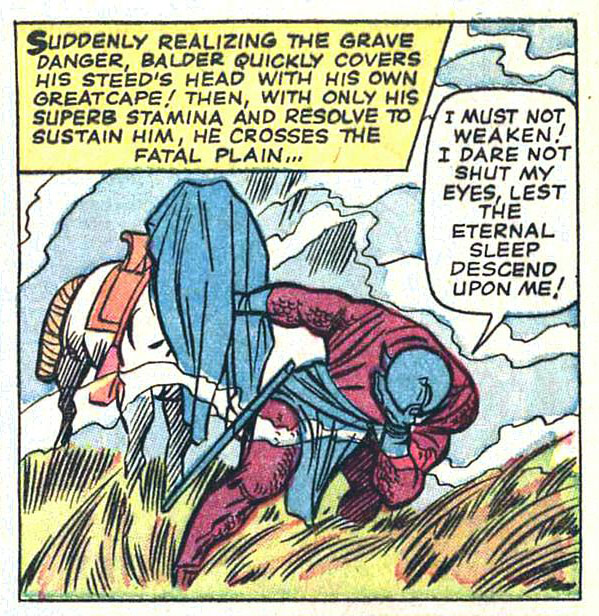

Panel 1: Comes to forest of sleep–plants give off gas

Panel 2: Covers horse’s head with cape and with superb stamina Balder just about staggers thru

Panel 3: X of swords X

Panel 4: X cape X flat rocks X hooves X

Panel 5: Reaches moving mountains X

Panel 6: Makes it to healer X

PAGE 15:

Panel 1: Thor must lift time warp–it’s a helluva way for the girl X

Panel 2: It’s better that she take the risk of dying–He can become Blake and try to save her

Panel 4: Hammer breaks warp X

Panel 5: No sooner does warp X

Panel 6: Medicine vial X

Panel 7: Medicine is X

PAGE 16:

Panel 1: Warp is lifted–only seconds to save girl

Panel 2: Take this, kid

Panel 3: X sword X

Panel 5: X balder X

Panel 6: Girl opens eyes X

Panel 7: Thanks X

Panel 8: Thor and gal walk X

What conclusions can one draw from this? Obviously something was in the process of changing, since only months before on other originals there are no Kirby notes at all. In the photocopies of Jack’s pencils from JIM #101 (previously seen in TJKC #14 and #18), no notes are visible; and since these are photocopies of pencil art, one would assume that if pencil notes were there, then they’d be viewable. Also, on other pages of original art from pre-1964, no notes are found (other than editorial notes left by Stan). So sometime during 1964 Jack begins the process of leaving notes in the borders of the artwork. Why? Were these to help remind Lee of a story they plotted weeks previously, or guide him through a story he had little input on?

In other books not drawn by Jack, where he is credited as “layout” artist, also from this time (64-65), he leaves even more detailed border notes. Why? Is he laying out art, plot, story, or what; and for whom— the artist or the writer or both? Some speculate that Jack may have just left border notes on the books he drew, having gotten into the habit after leaving notes on his “layout” books; but this JIM #111 story predates his layout books. It’s also well documented that, as time went on, on future stories Jack’s notes become even lengthier, describing characters and events in much more detail.

In future issues we’ll see other examples—judge for yourself what or who’s unfair (and to whom)!

The Last Straw?

A Failure To Communicate – Part Four

Thanks to Mike Gartland and John Morrow, The Kirby Effect is offering Mike’s “A Failure To Communicate” series from The Jack Kirby Collector. Captions on the illustrations are written by John Morrow. – Rand Part Four was first published in TwoMorrows’ April 1999 Jack Kirby Collector 24.

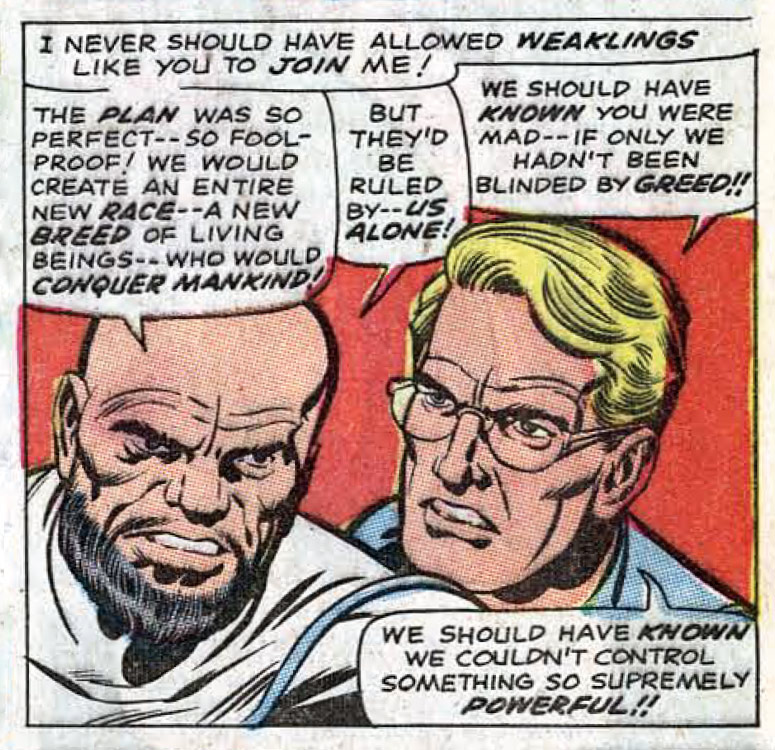

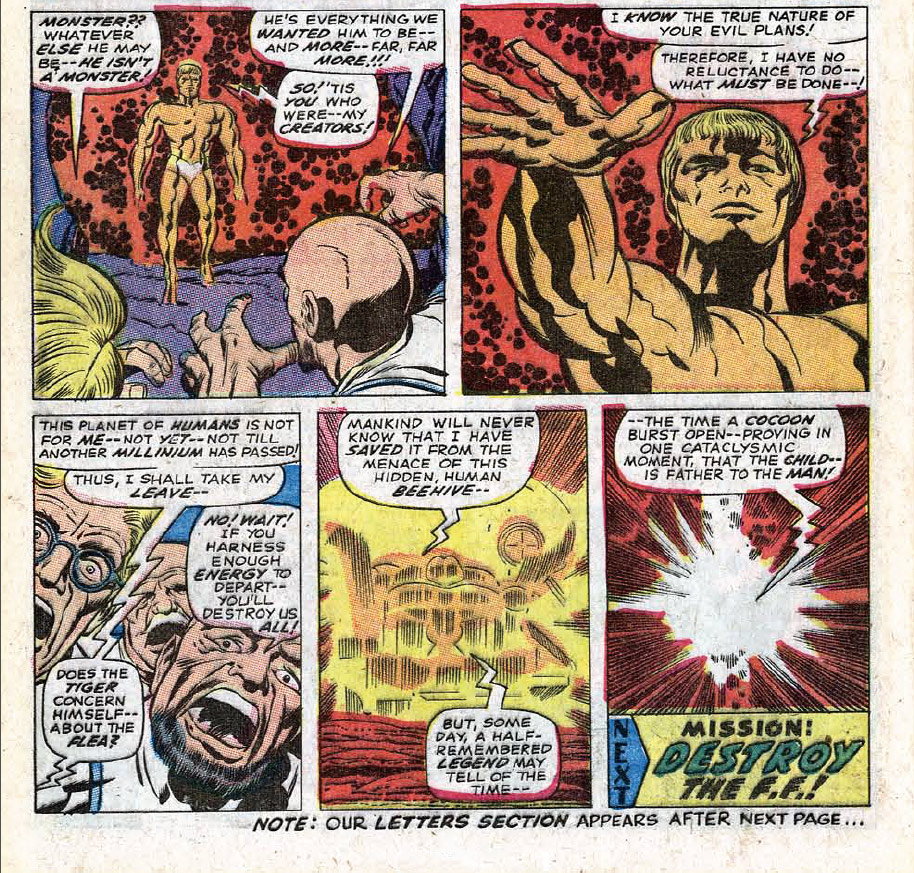

It’s the Summer of 1967, arguably the height of the ’60s. Among some of the things occurring (or “happening” as it was referred to then): Expo ’67 was in full swing, Sgt. Pepper was the album to ingest and discuss, the Arabs & Israelis experienced a bloody six-day war, there were race riots in Detroit that were just as bloody, and Vietnam kept rolling along, with Summer protests and young people dying. Definitely a time of turmoil for many, which brings us to… Marvel Comics?? Well, some will say turmoil is turmoil; and facts are facts; and A is A; and what has this to do with Kirby & Lee? Well… During that Summer of ’67, on the stands was the latest new adventure of Marvel’s then flagship title: The Fantastic Four. In June and July issues #66 and 67 premiered “The Mystery of The Human Beehive.” By this time, readers were so used to seeing new and inventive creations and situations in the pages of FF every month, they were almost becoming jaded. What no one realized at that time was, with this story, readers were taking in what would be the virtual end of an incredibly productive run.

A new Kirby character about to be born in “When Opens The Cocoon.”

First published in Marvel Comics’ October 1967 Fantastic Four 67′.

As we have seen in previous articles, during this time at Marvel Jack Kirby was becoming more and more disenchanted with his position with the Company and his working relationship with Stan Lee. Over the previous twelve months Jack witnessed Marvel receive a great deal of publicity; articles in newspapers and magazines hailing Lee for his new and innovative style, and how the readership wondered how Lee “came up” with characters like the Hulk, Thor, and Spider-Man, among others. Jack was also having his share of business battles with Goodman, a man who never understood Kirby’s value to the Company (Lee, to his credit, did), concerning his contract and his wanting to earn the most he could—and Jack was tired of submitting stories with his margin notes for direction, being either changed or ignored by Lee (by this time Kirby felt in control of the storylines, and felt that Stan should be following his margin notations when he dialogued those stories). This latest installment in FF #66 and 67 would become yet another dispute that would eventually help contribute to the end of Kirby’s creative generosity.

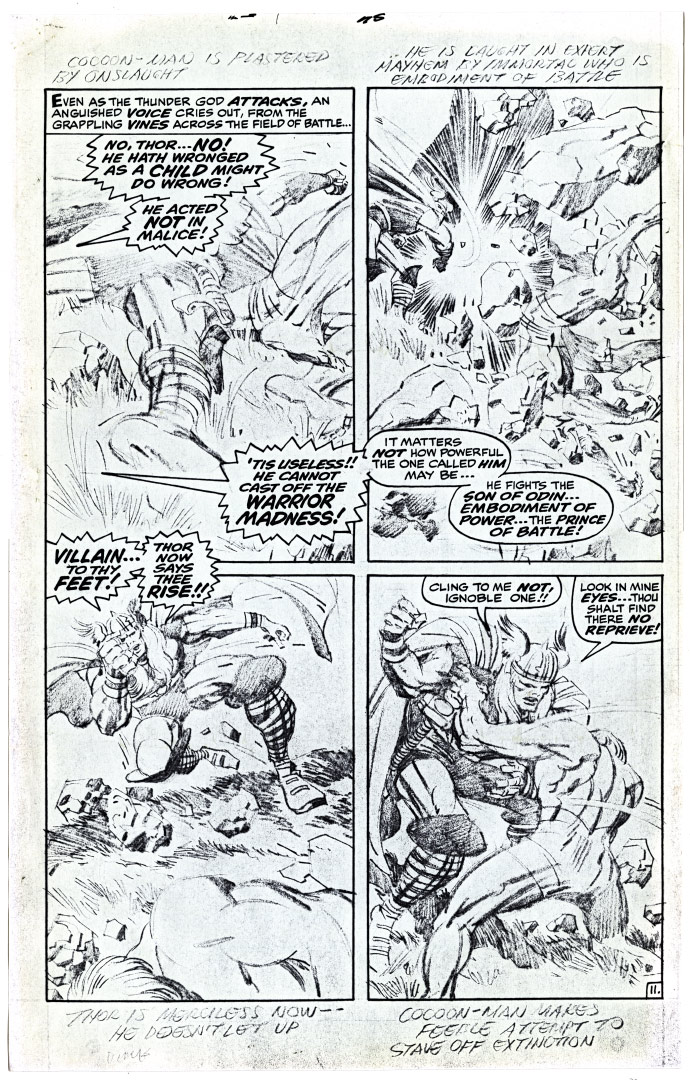

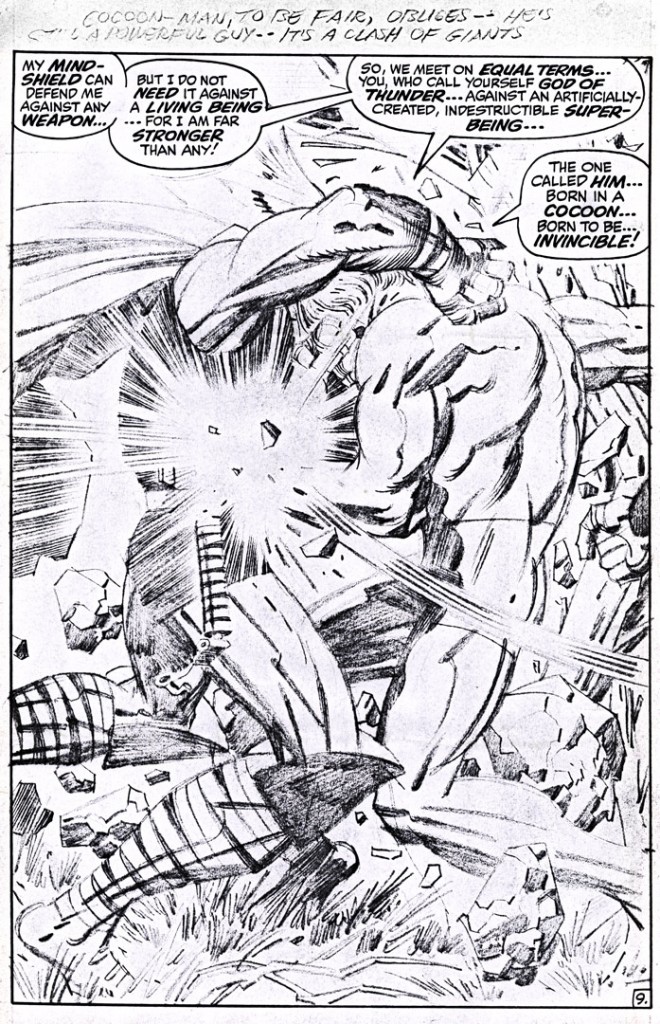

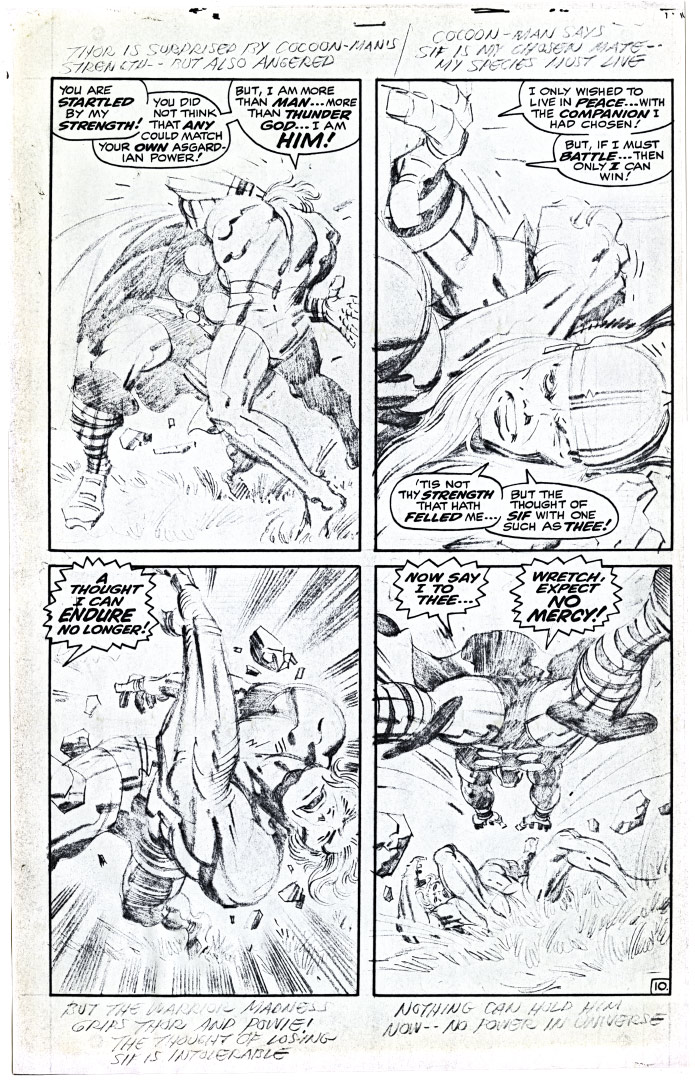

“Him” returns to do battle in “A God Berserk!

First published in Marvel Comics’ July 1969 The Mighty Thor 166.

Readers familiar with the storyline will remember that Alicia Masters was abducted in issue #65 (the usual plotteaser so often utilized by Jack to entice readers to “stay tuned” for the next issue) and taken to the mysterious “Citadel of Science” in which “The Human Beehive” exists. Technicians and scientists gathered together in secret to perform the most awesome of experiments: The creation of a perfect human being. The experiment grows more quickly than anticipated, however, and escapes without anyone being able to get a look at “him” due to the energy he radiates. They therefore need Alicia’s talents to sculpt a representation of “him.” The scientists unfortunately (and of course) harbor a secret from Alicia. In the next issue we learn that the scientists are creating this perfect human as the forerunner of an entire supreme race, to be dominated by the scientists in order to fulfill their dreams of world conquest. They will create the ultimate army that will conquer the world for their masters. The scientists refer to each other as “mad,” “greedy,” and “murderous.” Fortunately, the FF arrive in time to rescue Alicia, just as the supreme human is emerging from his “cocoon.” After the FF and Alicia have departed, the being, known throughout the storyline only as “Him” confronts his creators. He explains that Earth is not yet ready for him, and that he knows of his creators’ evil intent; he therefore will leave the planet, at the same time destroying the evil scientists, thereby rendering mankind a great unknown favor. After spouting a few more cliches, “Him” is gone. That’s how the story read; that wasn’t, however, how the story was written.

The return of “Him” in Thor 166 is one of many instances of Jack reusing established characters rather than creating new ones. While they still made for interesting stories, few ground-breaking concepts emerged from Kirby’s work after Fantastic Four 67.

As stated previously, the Sixties was a time of turmoil; there were more social changes occurring than had been seen in decades. Movements, philosophies, and even religions were being born in this decade, or were at least reaching public awareness. One of these movements would play an interesting role in Silver Age Marvel history. The philosophy of Objectivism was developed by its discoverer, Ayn Rand, in the late Fifties, gaining strength in the early-to-mid-Sixties. Explaining the fundamentals of Objectivism would, unfortunately, take up too much space here and I admit that I am not versed in it well enough to do it justice. So, with apologies to Objectivists and those more learned, please refer to the information below obtained from AynRand.org:

Objectivism

Objectivismanswers the questions posed in the five main branches of philosophy as Plato defined them which are:

- Metaphysics: The nature of the Universe which man has to deal with.

- Epistemology: The means by which he has to deal with it, ie. the means of acquiring knowledge.

- Ethics: The standards by which he is to choose his goals and values in regards to his own life and character.

- Politics: The standards by which he is to choose his goals and values in regard to society.

- Esthetics: The means of concretizing this view.

Objectivismanswers these branches thusly (again summarized):

- Metaphysics: Objective Reality. Reality exists as an objective absolute; facts are facts independent of man’s feelings, wishes, hopes or fears. (This is the famous “A is A” axiom.) Thus Objectivism rejects any belief in the supernatural—and any claim that individuals or groups create their own reality.

- Epistemology: Reason. Reason, the conceptual faculty, is the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man’s senses. Reason is man’s only means of acquiring knowledge. Thus Objectivism rejects mysticism and skepticism.

- Ethics: Self-interest. Man is an end in himself, not a means to the ends of others; he must live for his own sake; neither sacrificing himself to others nor others to himself. Thus Objectivism rejects any form of altruism—the claim that normality consists in living for others or society.

- Politics: Laissez-faire Capitalism. The only social system that bars physical force from human relationships. No man or group has the right to initiate the use of physical force against others. Man has the right to use physical force only in self-defense and ONLY against those who initiate its use. Thus Objectivism rejects any form of collectivism, such as fascism or socialism. Men must deal with one another as traders, giving value for value.

- Esthetics: Romantic Realism (does not apply to this article) Objectivism also rejects any form of determinism, the belief that man is a victim of forces beyond his control (such as God, fate, upbringing, genes, or economic conditions).

Source: AynRand.org

According to Mark Evanier (based on conversations he had with Kirby), Jack originally intended for this storyline to represent his take on the Objectivist philosophy. What Jack had read of Ayn Rand and had explained to him had gotten him to thinking about the philosophy and its pitfalls (some, of course, will dispute that there are pitfalls in it and that is their right), which led him to do a story about it. Jack probably did not consciously think, “Here’s my answer to Ayn Rand”; his primary goal was, as always, to just write a good story. But in Jack’s original story, the scientists are well-intentioned, with no evil plans. They are attempting to create a being totally self-sufficient, intellectually self-reliant; not encumbered by superstition, fear, or doubt; in short, a being based on Rand’s absolutes. Of course such a being would be totally intolerant of those who created him; a truly Objectivistic being would not cope with the flaws in others.

In the first part of the story, the scientists attack the being in an attempt to control him. This violates one of the doctrines of Objectivism; also, the scientists are conducting this experiment for the benefit or betterment of mankind—another violation. The being destroys his creators at the end of the story not to help mankind, but because in his eyes they are evil; no matter how well-intentioned, they tried to destroy him. He is allowed to act in his own self-defense; remember, in the eyes of the Objectivist there is no gray area between good and evil. On the other hand, Jack simply may have wanted to show on that last page the vast difference between Altruism and Objectivism; the scientists, thinking of their fellow man, create a totally self-interested being who, of course, uncaringly destroys them because they don’t meet with his criteria. Whatever the case, according to Evanier, when Stan received the first part of this storyline, he felt that changes had to be made. Perhaps he found its content too negative to a given philosophy, politically-based, or simply confusing to him. Stan didn’t notice any villain in the story and almost always felt that every story had to have a bad guy, so he had to come up with one. He could only choose between the being or the scientists and it was simplicity to just go the “Mad Scientist/Sympathetic Creature” route; it worked for Frankenstein, right? During these years Stan would have photostats shot of Jack’s artwork, to be sent back to Jack so that he could remember his plot continuities in these multi-part stories of his. These photostats would have Stan’s dialogue intact to show Jack how Stan was interpreting the stories. When Jack received the photostats to issue #66, the first part, he wasn’t pleased at all. His storyline had been corrupted; the entire reason for the story had been gutted, replaced with a standard comic book plot; and he was now (due to the fact that this issue was going to print) forced to change the rest of his story to support Lee’s version. Jack may have intended for this story to be longer, but after seeing this, the story would be ended with the next issue. The story that Jack wanted: “Create a superior human and he just might find you inferior enough to get rid of,” became through Lee another “bad guys try to take over world and get their comeuppance” story. Creatively, Jack had reached another impasse with Lee. It was no longer as it was when they worked together just a few years previous, where they would have long plot discussions and the stories were kept simple. As Marvel began to grow in scope, the workload for Lee became more and more involved; what with editing stories and art, Stan also had to help write stories for practically every title, working with many other artists—not to mention business meetings and publicity appearances. As read in the now-famous (or “infamous”) interview of Stan for the magazine Castle of Frankenstein, Stan gave little input to Jack concerning stories during this time, having full confidence in Jack’s ability to continue coming up with new characters and situations. Jack was on his own, communicating plots with Lee briefly, with Stan not knowing what was coming up in the next issue on many occasions. Unfortunately, Stan considered Jack’s input on these stories as “plots,” whereas Jack thought of them as “stories,” meaning that he, Jack, was the writer, not Stan. As Jack was left more and more to his own devices, he found it more and more intolerable to accept the changes that Lee would make to his stories, and throughout the whole thing, take credit as the writer of these stories. They were growing apart, and in more or less different directions.

Their collaborations clicked best when they worked on hero vs. villain (or hero vs. hero), single-story, human frailty, Earth-bound plots; but now Jack’s stories were becoming very complicated plots, continuing over several issues, involving ideas and concepts touching on mythology, space, science, religion, philosophy, and politics. The scope was becoming grander and grander. Stan shined when he wrote about the human condition, but Jack was now reaching for the stars and what was beyond humanity. With the conclusion of this story (and while this was by no means the main reason, it was a biggie— but there were apparently dozens of other reasons), Jack decides that he has given enough new characters, devices, and situations to Marvel. He had seen one after another of his creations and/or stories changed against his wishes or taken away from him. He didn’t really want to stay at Marvel anymore, but at this particular time there weren’t any avenues open to him that would offer him any better working conditions; so he figured he’d have to make the most of it. He just wouldn’t give them anything new anymore, or at least anything that was to him substantial. Lest anyone doubt the creative input from Kirby, from November ’65 to November ’67—two years where Jack was pretty much doing the stories on his own, plus plotting for other books that he wasn’t drawing—from the imagination of this man came: Black Bolt, Gorgon, Crystal, Triton, Karnak, Lockjaw, Galactus, The Silver Surfer, Wyatt Wingfoot, The Black Panther, Klaw, Sub-Space (later dubbed The Negative Zone), Blastaar, The Sentry, The Supreme Intelligence, The Kree, Ronan, Him, Psycho-Man, Hercules, Pluto, Zeus and the Greek Pantheon, Tana Nile and The Space Colonizers, The Black Galaxy, Ego the Bioverse, The High Evolutionary, Wundagore and The New-Men, The Man- Beast, Ulik, Orikal, The Growing Man, Replicus, The Enchanters, The Three Sleepers, Batroc, A.I.M., The Cosmic Cube, The Adaptoid (who later becomes The Super- Adaptoid), Modok, Mentallo, The Fixer, The Demon Druid, The Sentinels, and The Mimic. This is not complete as secondary creations such as The Seeker, Prester John, The Tumbler and others weren’t mentioned; but they all premiered within the two-year period.

After November ’67, for the last three years that Jack worked for Marvel, you get the exact opposite; many secondary characters, but very few memorable ones. In FF, the only character of note after November ’67 is Annihilus. In Thor you have Mangog and possibly The Wrecker. In Cap you could consider Dr. Faustus and The Exiles. Jack does some good work with some of the classic characters like Dr. Doom, the Mole Man, and Galactus among others. Even the “Him” character is brought back in Thor #165 and 166 in a pretty standard Kirby slugfest. (It’s interesting to note that throughout the story, Jack refers to the character as “Cocoon Man”; perhaps Jack objected to the “Him” name?) In any event it’s pretty obvious where “The House of Ideas” got their “ideas” from; but now the “house” was being put under creative foreclosure; towards the end, it was said (but unsubstantiated) that Jack was asking Stan to come up with “ideas” for the stories, which is why you have characters like The Monocle, the Crypto-Man, and a retread of The Creature from the Black Lagoon in the last few Lee/Kirby issues.

Many pundits believed that the creative spark was waning, but Jack was merely biding his time until something better came along. New and exciting characters were still being created by Jack, but Marvel wouldn’t get them. The New Gods was a concept nurturing within Kirby’s brain while he was still at Marvel; but because of a failure to communicate, it would always remain a tale of “what might have been.”

(Our thanks to Mark Evanier for background information for this article.)