Previous – 12. Ghosts In The Attic | Contents | Next – 14. The Art Of The Swipe

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

ALL OR NOTHING AT ALL

After the war ended, the world once again descended into two great spheres; East vs. West, democracy vs. Communism, us vs. them! With the fall of Hitler, the Communists became the great Bogeyman. In a speech in 1947 the “good Jew” Bernard Baruch described the global situation as a “Cold War” spinning out of control. The Korean conflict and the Reds getting the bomb in 1949 due to Julius Rosenberg’s treachery, dominated the headlines. Movies such as The Red Menace and I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. focused much attention on the country’s paranoia. Sen. Joe McCarthy started a famous campaign to uncover Commies working undercover in the Govt. Could comics be far behind?

On June 19th 1953, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were put to death by way of electrocution; thus ended one of the worst episodes of Jewish shame in U.S history.

Alas, there was no Harry Slonaker for Ethel and Julius. Their method of escape was joining up at Communist Youth clubs, where they rallied with labor unions for the betterment of the workers. The Communist youth groups were popular among the poor. They both graduated into the official Communist Party. When the fighting had ended, suddenly it was Communist Russia—earlier an ally, now seen as our biggest threat. After the war they joined a network of similarly minded people and began slipping American nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. Julius and other mostly Jewish accomplices were arrested for spying in 1950. When Julius wouldn’t finger anyone else, J. Edgar Hoover ordered his wife arrested–suspecting it would force him to confess and name names. Julius refused; they were tried and sentenced to death. The only members of the group so sentenced due to their unwavering claims of innocence and unwillingness to finger others. The stain of their treachery attached itself to all labor groups, and other Jewish intelligentsia who had dabbled with Communism in their youth.

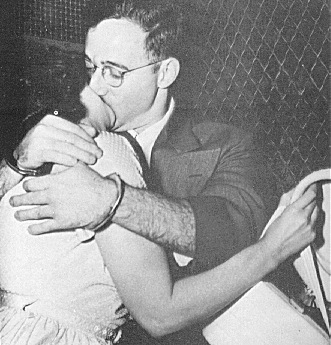

Love kept them together-till the bitter end

The Jewish community was torn between the love of country and their fear of retaliation from the anti-Semitic populace- always eager to blame all Jews for the crimes of one. The inequality of the sentences for the Rosenbergs, as compared to their fellow conspirators riled many. Peoples as disparate as the Pope, Albert Einstein, Picasso, and John-Paul Sartre lobbied President Eisenhower for leniency. Sartre would describe the trial as “a legal lynching which smears with blood a whole nation. By killing the Rosenbergs, you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic, witch-hunts, autos-da-fé, sacrifices — we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear… you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb.” On early Friday evening of June 19th they were executed- the only American civilians ever executed for espionage. Though their guilt is not debatable, the depth of culpability is still debated. Boris V. Brokhovich, the engineer who later became director of Chelyabinsk-40, the plutonium production reactor and extraction facility which the Soviet Union used to create its first bomb material, denied any involvement by the Rosenbergs. In 1989, Boris V. Brokhovich told The New York Times in an interview that development of the bomb had been a matter of trial and error. “You sat the Rosenbergs in the electric chair for nothing”, he said. “We got nothing from the Rosenbergs.”

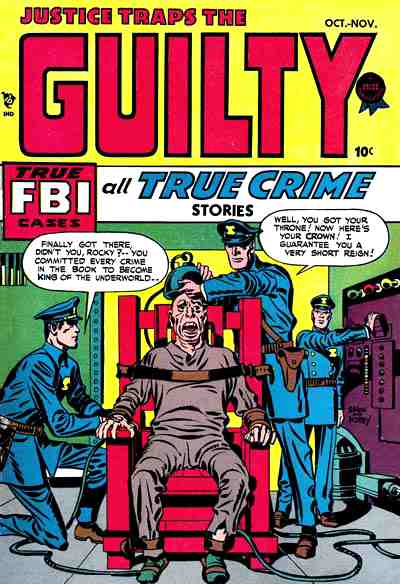

S&K had an electric chair too

Perhaps in response to the anti-Jewish backlash, or a feeling of shared Jewish guilt, some of the comic owners went out of their way to show their all-American feelings. Reams of spy comics were produced. The Catholic Church began a series of strongly anti-communistic screeds and eventually the super-hero genre. Captain America, the great S&K political hero of World War 2 had been cancelled after the war due to lack of interest, but with the rise of the anti-Commie fervor, Atlas brought back the red, white and blue hero in late 1953 in Young Men Comics #24, coincidentally timed to the Rosenberg execution. Relabeled as Captain America-Commie Fighter, the character regained his own series in early 1954. Taking on Commie spies and saboteurs, Cap and Bucky acted like they had never left. Submariner and Human Torch soon followed. The new series disappeared after only 3 or so issues, except for Submariner which lasted few months longer in hopes of a TV series.

It wasn’t only the comics that noticed a market for Cold War intrigue. In 1953 a long-time British Intelligence officer named Ian Fleming ignited a whole new genre when he released Casino Royale featuring super-spy James Bond-007.

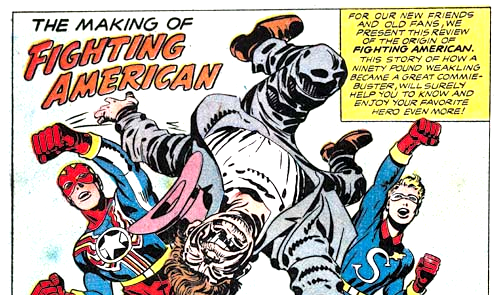

Joe Simon had noticed the return of their iconic patriotic hero. Not to be outdone, he and Jack decided to get back into superheroes with their own Commie basher. Fighting American debuted with its own series published by Prize, cover dated April/May 1954. FA had a very interesting origin gimmick. Johnny Flagg was a radio commentator who specialized in anti-Communist propaganda. A war hero, left lame from a battle wound, he tirelessly fought to keep America safe. Johnny’s brother, Nelson was a weak milquetoast who loved his brother and country. During a series of broadcasts spotlighting a Commie scam to raise money to finance sabotage Johnny is nabbed and beaten to death. Swearing revenge, Nelson is asked by the Government to help out in a scientific experiment. The government had learned how to revitalize a lifeless body and improve it to almost superhuman limits. What the Gov’t needed was a life force to re-animate the new body. It fell to Nelson to willingly give his life to bring back his brother. After some preparatory procedures Nelson is strapped to a transfer chair where his life force is drawn from him and given to his dead brother. What emerges is the first original Cold Warrior, a hero created and dedicated to bring about the end of the Evil Empire.

All commies had bad teeth

From there, Fighting American would pick up a kid sidekick titled Speedboy when he is caught changing into his costume by a page boy at the radio station. This updated Captain America and Bucky began a spectacular legacy of bashing colorful Commie sympathizers.

It all became a big joke

Around this time, Sen. McCarthy’s popularity nosed dived when the respected journalist Edward R. Murrow took him on in a televised segment and exposed him as a hypocritical bully and blowhard. With the Senator reduced to a joke, Joe quickly changed directions for FA, changing the series from a serious adventure strip into the first satirical super-hero. From deadly saboteurs, the villains suddenly became colorful clowns and buffoons such as Rhode Island Red, Hotsky Trotsky, and Rimsky & Korsakoff. The action changed from seriously deadly to slapstick comedy. Joe commented: “Jack and I quickly became uncomfortable with Fighting American’s cold war. Instead we relaxed and had fun with the characters. As one critic wrote, “The fun ran rampant, Flying fists, facetious frolics and names from The American Dictionary of Silly Surnames set the mood for a series of epic stories of intrigue and idiocy.” Jack recalled in an introduction to a reprint collection. “The magazine had not only “punch and power” but still another flag to wave–satire–ingratiating and wonderful satire!…..To put it bluntly, the formula for the magazine called Fighting American was “laugh a minute in a roller coaster on its way down to the center of a meat grinder.”

Jack’s return to drawing super-heroes was flawless. His power and grace combined with a naturalness drawn from his romance strips gave his art a more illustrative dimension. His extreme stock poses and layouts on FA became the template and guidelines that controlled all his future superhero work. The first appearance of a future Kirby icon showed up in issue #3 when Kirby unveiled a single page 9 panel fight ballet. Another Kirby staple continued when Fighting American went undercover and joined a movie production staged by villains.

The comic industry had rebounded from the immediate post war slump, but by 1954, sales were again plummeting. The combination of the new technology of TV, plus the growing ill repute being heaped upon the industry took its toll. There were municipal hearings to ban comics. Some staes banned the books. There were numerous articles in newspapers and magazines excoriating comics and a supposed connection to juvenile delinquency. Religious and social leaders bonded together to organize book burnings and boycotts. Dell Publishing became the new comic publishing powerhouse due to its squeaky clean child safe Disney and TV and movie take-offs. No barber shop would ever be without them.

From a high of 609 separate titles in 1953, the industry plummeted to little more than 400 by 1955. Though sales and publishers were falling to the wayside, Simon and Kirby maintained their position with 4 solidly selling titles. But Jack and Joe were scrambling, comics were hurting so maybe they should try other venues. Joe Simon had a story he had been working on for a while about a struggling rag industry businessman at the end of his rope; and a savior—a messiah– in the guise of his brother David. The story didn’t lend itself to a comic book treatment, so Joe gave Jack the outline and Jack worked it up into a proposed TV script called The Messiah.

It is a gentle tale of a man given a second chance via his faith and the love of a good woman. The dialogue is gentle, and poignant, and humorous in a Jewish borscht belt vein. In the midst of his despair, the man confronts God and challenges him, his wife chastises him. “Don’t be so smart about the Messiah. He can come tomorrow. He can come now, this minute. He can come through that door over there and He’ll say Milton Farber, you’re as big as any man. You should be ashamed of losing your spirit” It’s not a stretch to imagine that Roz had often confronted Jack with similar encouragement during his dark periods. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that the story takes place in a garment district textile factory, and the man is a clothing manufacturer, replete with union concerns and behind the scenes deals. It’s not known if they shopped this script to any producers, but it certainly deserves to be seen on a stage, maybe even a musical to rival Fiddler on the Roof.

Printing presses were looking for clients to fill their lost quota of product. While still maintaining their contractual output for Crestwood just in case they belly-flopped, S&K took every royalty penny they had built up since the end of World War Two, along with the distribution clout of paper and printing broker George Dougherty, Jr. (a long-time paper broker for the lumber industry whose father had been one of the printers at Eastern Color on Funnies On Parade back in 1933) who was fronting the paper. A commonplace 25% deposit was advanced by Leader News to World Color Press in Sparta, Illinois against projected sales to cover the printing and engraving costs. Joe and Jack felt they were making all the right moves utilizing the expertise of Nevin Fidler, who also owned a small piece of the action. Nevin Fidler was a friend who had been an office director at Crestwood, and was familiar with all the production people. Joe had dreamed of this freedom for a long time, at least as far back as when they sold Crestwood on romance comics. So he leapt at the chance. The distributor chosen was Leader News, an independent whose largest client was EC Comics.

Leader came into being when Mike Estrow broke up his pulp Trojan distributor with the new comic distributor to be Leader News. Leader News’ independence meant that the smaller publishers would flock to them as their commission was lower and shipping standards weren’t too high to demand stellar service. Most of Leaders’ clients were the hit and miss small print variety. It’s been said that DC’s Jack Leibowitz was a silent partner. And that he would point small companies to Leader when they were too small to use DC’s distribution firm. Being without the bigger selling books, Leader News had no clout and was always one step from the creditors. William Gaines recalls in an interview for the Comics Journal.

“No, no, we were putting out what we thought was selling. We were like the smallest, crummiest outfit in the field at that point with definitely the worst distributor, Leader News. When he (Max Gaines) went back in business, he was without contracts, he didn’t have his characters any more, he didn’t even have Shelly Mayer, because Shelly Mayer was up at DC, and this was the best distributor he could get. And when he got killed, Leader News became my distributor.”

Two page spreads back in action

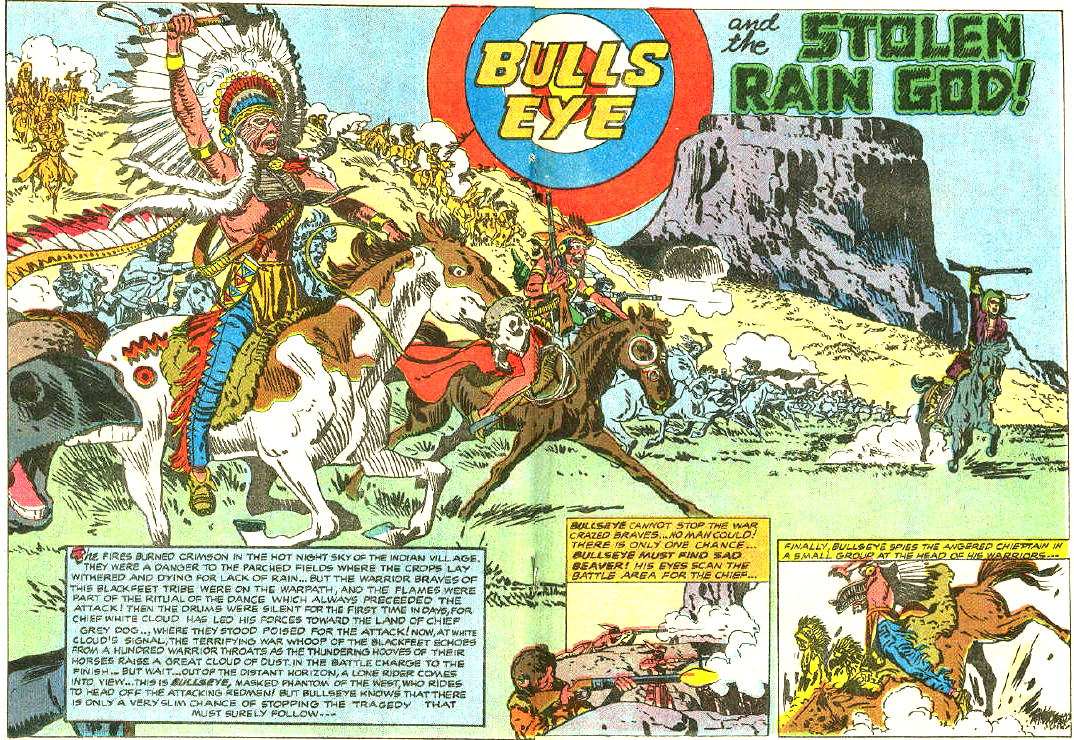

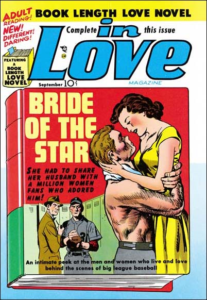

Joe and Jack went all in and immediately produced four new titles, each covering a specific genre. Bullseye was a western with a masked vigilante slant. In Love was a romance book,  Police Trap was a crime comic with a pro-police POV, and Foxhole was S&K’s first venture into the growing war comic genre. War comics had increased in popularity since the US involvement in the Korean War.

Police Trap was a crime comic with a pro-police POV, and Foxhole was S&K’s first venture into the growing war comic genre. War comics had increased in popularity since the US involvement in the Korean War.

While the content of the Mainline books were nothing revolutionary, several aspects of the titles deserve mentioning. Foxhole –billed as war stories as seen by the guys in the foxhole– featured tales written by actual vets; Pvt. Jack Kirby among them. Several stories featured Kirby’s byline as writer. Kirby also produced a series of covers for Foxhole as good as any title ever had. Bullseye continued Kirby’s preoccupation with the western orphaned child raised by an older mentor and trained as a sure shot. When the mentor is killed by a villain, the young teen avenges the murder by killing the villain. This time they added the concept where, after mistakenly charged with a crime, the young lad dons a mask and uses his skills as a masked vigilante, and scout. The character had a great visual focus when the child is branded with a bullseye on his chest.

In Love was packaged as a complete novelette in every issue. The story for issue #1 was an incredible 20 pages long. The second issue would feature the rejected strip Inky reformatted into a comic book story. And Police Trap was written from the perspective of the policeman rather than the mobsters—perhaps an homage to the radio and TV series Dragnet.

A new page to tie Inky together for the comic

Joe and Jack never stopped conceptualizing, while working on the four ongoing titles; they still worked on other ideas. They considered bringing back super-heroes. They worked up artwork for at least three new characters, Night Fighter, Sunfire and Sky Giant. Of most interest is Night Fighter.

The two presentation pieces seem to show a goggle eyed hero who could walk up walls, and sported some sort of gun. These specific aspects would be revisited in a couple years for a more important project. It’s not sure if they were connected. One dummy cover shows a split book featuring two super heroes very similar to the format that Marvel would use later, even down to the small graphic in the upper left hand corner.

Times were getting tough for small undercapitalized ventures. Ross Andru and Mike Esposito’s company folded. Jack’s young protégé Martin Rosenthall had joined Mikeross as a partner. When they failed, Rosenthall contacted Jack and sold some of the company’s assets to Mainline. Several completed stories found homes in S&K publications.

Not bad for a swipe Hold that hill-Wertham and Kefauver charging hard

The next problem was to be more worrisome. The undercurrent of social protest against comic books reached the surface. The pressure had been building since comics first began. There had been slight eruptions over the years, but in April 1954 the top blew off during a series of Congressional hearings.

2-page classic

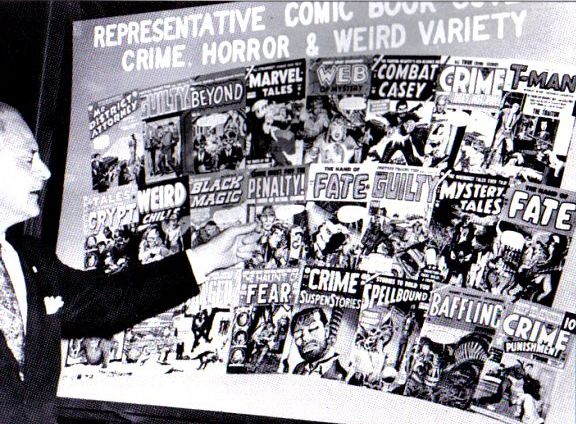

As with all low brow entertainment, there had been a segment of the population that had always condemned comics as a hazard to young sensibilities. The raucus, racy, and reckless nature of some publishers had created a climate of disdain and anger from citizens groups, religious leaders, and well known medical people. Organized book burnings were sprouting up. In several well publicized articles a well known psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham had made the dangers of comic books a personal crusade. In April 1954, he published a well received treatise entitled Seduction of the Innocent, which spotlighted the questionable connection between comics and juvenile delinquency. In a format similar to Anthony Comstock’s earlier screed Traps For The Young, that excoriated the juvenile series books, it laid a large segment of juvenile delinquency squarely at the feet of the crime, horror, and romance comics, singling out EC’s horror titles as the worst offender.

The biggest threat was that Dr. Wertham was no glory seeking hack, or political poseur. Wertham was a well respected Dr. who could articulate and verify all his claims-at least to the general public. Born in Germany, in 1895 to Jewish parents he went into psychiatry after communicating directly with Sigmund Freud. He came to the US in 1922 after some religious backlash. He landed at prestigious Johns Hopkins University and joined the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic. In 1932 he moved to New York to head up the Courts Psychiatric Evaluation Unit and gave testimony on the various felons and convicts on their behavior and ability to stand trial.

He took up the cause of stopping comics, as well as TV, mass media, and other forms of communication after heading up a juvenile psychiatric ward at Belleveu. He wrote articles, gave talks, and held debates to back up his theories. He published his book Seduction of the Innocent —which led to hearings in front of the US Senate.

A few days later, a Senate Subcommittee held hearings on juvenile delinquency. Chaired by Sen. Estes Kefauver the committee heard from many sociologists, medical specialists, (including Wertham) crime fighters, and religious leaders telling of the connection between comics and j.d. Then they turned to comic professionals to get their take. Things were actually going well until EC’s Bill Gaines took the stands, Gaines arrogantly unapologetic testimony seemed to solidify all the prurient uncaring notions thrown at the industry. Charges of prurient females with large protruding breasts, and comic overkill hurt the image. Perhaps the worse testimonies was by Dr. Wertham, who claimed that many stores were reluctant to sell the offending books, but were forced to by the magazine distributors who refused them other magazines if they didn’t take the comics as well.

From Dr. Wertham’s testimony;

Dr. WERTHAM. This tremendous power is exercised by this group which consists of three parts, the comic book publishers, the printers, and last and not least, the big distributors who force these little vendors to sell these comic books. They force them because if they don’t do that they don’t get the other things.

Mr. HANNOCH. How do you know that?

Dr. WERTHAM. I know that from many sources. You see, I read comic books and I buy them and I go to candy stores.

They said, “You read so many comic books.” I talk to them and ask them who buys them. I say to a man, “Why do you sell this kind of stuff?”

He says, “What do you expect me to do? Not sell it?”

He says, “I will tell you something. I tried that one time.”

The man says, “Look, I did that once. The newsdealer, whoever it is, says, ‘You have to do it’.”

“I said, ‘I don’t want to’.”“‘Well’, he says, ‘you can’t have the other magazines’.”

So the man said, “Well, all right, we will let it go.”

So when the next week came, all the other magazines were late. You see, he didn’t give them the magazines. So his was later than all his competitors, he had to take comic books back.

I also know it another way. There are some people who think I have some influence in this matter. I have very little. Comic books are much worse now than when I started. I have a petition from newsdealers that appealed to me to help them so they don’t have to sell these comic books.

S&K fully involved

One of the stranger aspects dealt with Wertham painting organized opposition to his theories as Communist conspiracies promoted by the comic companies. (perhaps a swipe at Lev Gleason)

Curiously, one Senator tried to get the doctor to condemn the writers and artists who made these horror stories but Dr. Wertham would have none of that.

Senator HENNINGS. Doctor, I think from what you have said so far terms of the value and effectiveness of the artists who portray these things, that it might be suggested implicitly that anybody who can draw that sort of thing would have to have some very singular or peculiar abnormality or twist in his mind, or am I wrong in that?

Dr. WERTHAM. Senator, if I may go ahead in my statement, I would like to tell you that this assumption is one that we had made in the beginning and we have found it to be wrong. We have found that this enormous industry with its enormous profits has a lot of people to whom it pays money and these people have to make these drawings or else, just like the crime comic book writers have to write the stories they write, or else. There are many decent people among them.

Let me tell you among the writers and among the cartoonists ─ they don’t love me, but I know that many of them are decent people and they would much rather do something else than do what they are doing.

Dr. Wertham reads some trash – Sen. Estes Kefauver – Bill Gaines

The owners of squeaky clean Dell Comics tried to add in facts and a subtle dig at the Doc.

TESTIMONY OF MRS. HELEN MEYER, VICE PRESIDENT, DELL PUBLICATIONS, ACCOMPANIED BY MATTHEW MURPHY, EDITOR, DELL PUBLICATIONS, NEW YORK, N. Y.

Mrs. MEYER. Mrs. Helen Meyer, 231 Montrose Avenue, South Orange, N. J. I am vice president of the Dell Publishing Co.

Mr. MURPHY. My name is Matthew Murphy, of 294 Bronxville Road, Bronxville, N.Y. I am employed by Western Printing & Lithographic Co., as Dell comics editor.

The CHAIRMAN. You may proceed.

Mrs. MEYER. Although we are not here to defend crime and horror comics, the picture is not as black as Dr. Wertham painted it. We must give our American children proper credit for their good taste in their support of good comics. What better evidence can we give than facts and figures. Here they are:

Dell’s average comic sale is 800,000 copies per issue. Most crime and horror comic sales are under 250,000 copies.

Of the first 25 largest selling magazines on newsstands – this includes Ladies Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post, Life, and so forth ─ 11 titles are Dell comics, with Walt Disney’s Donald Duck the leading newsstand seller. Some of these titles are: “Walt Disney’s Comics”; “Warner Bros. Bugs Bunny”; “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse”; “Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, Porky Pigs”; “Walter Lantz Woody Woodpecker”; “Margie’s Little Lulu”; “Mom’s Tom and Jerry.”

The newsstand sales range from 950,000 to 1,996,570 on each of the above mentioned titles. I mean newsstands only and I am not including any subscriptions, and we have hundreds of thousands of subscriptions.

With the least amount of titles, or 15 percent of all titles published by the entire industry; Dell can account for a sale of approximately 32 percent, and we don’t publish a crime or horror comic.

Dr. Wertham, for some strange reason, is intent on condemning the entire industry. He refuses to acknowledge that other types of comics are not only published, but are better supported by children than crime and horror comics. I hope that his motivation is not a selfish one in his crusade against comics. Yet, in the extensive research he tells us he has made on comics, why does he ignore the good comics? Dell isn’t alone in publishing good comics. There are numerous outstanding titles published by other publishers, such as Blondie, Archie, Dennis the Menace, and so forth. Why does he feel that he must condemn the entire industry? Could it be that he feels he has a better case against comics by recognizing the bad and ignoring the good?

Lev Gleason, head of Gleason Publishing and a staunch first amendment defender, volunteered to face down the committee and try to smooth out the ripples from Gaines testimony. Though the committee never acknowledged a concrete link between comics and juvenile delinquency, the damage was done.

This period of history is complicated. I am of at least two different viewpoints. I think the government and legislative overkill is wrong, totally Un-American. The same as the HUAC hearings. The results are always a lessening of American values. But as an adult viewer, I must admit that some publishers crossed a line. Left unstopped, they would have gotten worse. There was no outside brake that controlled the output of these companies. The only control was left to the publishers whose only concern was the bottom line. Self-censurship was really the only way to go. Like the Hays Committee, TV, and other pop culture clashes, these cures had to come from the industry itself, or face the possibility of Government oversight. The details could possibly be argued, but not the intentions. Something had to be done to stop the outrage. This outrage came from the only party that counted, the consumers. Wertham was wrong, but his crusade was right. The comics had overstepped the bounds of decency. And it was left to the comic pros to make it right. One analogy might be found in the later Anti-war movement. Many might agree on the principle, but they were lost when the movement overstepped and blew up College buildings and killed people. Overstepping invites Govt. intrusion, which leads to Govt. overkill. Better to separate from the bomb throwers willingly.

An actual voice of reason Lev Gleason – Dick Ayers troubled

Joe says the din over comics never affected them much, they were sure that their books were wholesome. Imagine their chagrin and consternation when one of the first objectionable comics offered into evidence was a copy of Black Magic. Joe recalls; “Watching this on TV I cringed- like I was suddenly thrown into a steaming vat in a horror comic.” Jack hoped the storm would pass over—but he knew the image of a comic reader was strictly lowbrow. “If you bought a comic book the reaction was there goes a guy who shoots pool—another lowly pastime. But some comic artists were very affected. Dick Ayers, in his biography talks about the horror of reading Parents Magazine and finding that several of his books were listed as objectionable, and being called a pornographer by a guest at a cocktail party and almost coming to blows. Dick became so distraught that he actually held a book burning of his books in his fireplace. Jack was more stoic; “I was only hoping that it would come out well enough to continue comics, that it wouldn’t damage comics in any way, so I could continue working. I was a young man. I was still growing out of the East Side.” Other artists were in a whirl. Jack Cole, creator of the family friendly Plastic Man fled the industry. Doing racy gags, and Playboy cartoons, much like Bob Wood, didn’t help. His personal life took a downturn and one day he drove to a shop, bought a rifle, drove to a secluded area and blew his brains out. Many turned to the advertising field, and some to fine art work. Some adventure artists took lower paying and lower presence work in DC’s romance division. Stan Lee’s Atlas Company tried to absorb many of the EC artists to supply filler stories for the many faceless titles.

Joe says the din over comics never affected them much, they were sure that their books were wholesome. Imagine their chagrin and consternation when one of the first objectionable comics offered into evidence was a copy of Black Magic. Joe recalls; “Watching this on TV I cringed- like I was suddenly thrown into a steaming vat in a horror comic.” Jack hoped the storm would pass over—but he knew the image of a comic reader was strictly lowbrow. “If you bought a comic book the reaction was there goes a guy who shoots pool—another lowly pastime. But some comic artists were very affected. Dick Ayers, in his biography talks about the horror of reading Parents Magazine and finding that several of his books were listed as objectionable, and being called a pornographer by a guest at a cocktail party and almost coming to blows. Dick became so distraught that he actually held a book burning of his books in his fireplace. Jack was more stoic; “I was only hoping that it would come out well enough to continue comics, that it wouldn’t damage comics in any way, so I could continue working. I was a young man. I was still growing out of the East Side.” Other artists were in a whirl. Jack Cole, creator of the family friendly Plastic Man fled the industry. Doing racy gags, and Playboy cartoons, much like Bob Wood, didn’t help. His personal life took a downturn and one day he drove to a shop, bought a rifle, drove to a secluded area and blew his brains out. Many turned to the advertising field, and some to fine art work. Some adventure artists took lower paying and lower presence work in DC’s romance division. Stan Lee’s Atlas Company tried to absorb many of the EC artists to supply filler stories for the many faceless titles.

In order to avoid legislative censure, the comic industry agreed to once again self-censure the books. An earlier manifestation had petered out with time. With the creation of the Comics Code Authority, the major companies united to self-regulate. They agreed to limit or end all types of violence, horror, and risqué matter. In what is often called the EC section the code states.

burning up a college education

No comic magazine shall use the word “horror” or “terror” in its title.

All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

Bill Gaines railed against this section, noting that the words “horror” and “terror” were parts of two of his best sellers. Gaines was sure that this section was set up purposely to put him out of business. It seemed to work as sales of EC books dwindled to insignificance.

It was suggested that the word “crime” should also be banned from a comic book title, but Lev Gleason, the publisher of Crime Does Not Pay fought tooth and nail to get that restriction stopped. It didn’t matter, with-in a year Gleason closed up shop for good. Gleason was more respected among his peers and had been fighting the backlash for years—even debating Dr. Wertham on radio and TV. Gaines was seen as more of a Johnny- come-lately and a bomb-thrower among his peers. Ironically, Gaines would get the last laugh. After the code appeared, Mad Magazine became so large of a success that DC bought out Gaines and added it to their portfolio.

Very quickly problems crept up. Their ruse to hide the new company from Prize didn’t last long. Prize’s reaction was that when S&K started their own company Prize cut back their assignments on the romance and crime titles. All that remained was Fighting American and Black Magic. It appears that Prize wouldn’t let them compete head to head on genres, so when S&K did their own romance book, then Prize took them off Young Romance and Young Love. A self published crime book and no more work on Justice Traps the Guilty. The 67 issue run on Young Romance was the longest uninterrupted stint that Jack had produced in his career to that point.

Times were horrible, pressure from outside, pressure from within. Prize kept threatening, Leader News went bonkers, artists kept demanding. Sales on the new titles were lackluster, and very soon money became tight. In an effort to cut back on expenses, Joe reused some artwork and reworked it into new stories, mostly for the Prize titles. Joe swiped a Manhunter story from 1943 for a Fighting American story, plus a Jack Burnley Starman story from 1942 for another Fighting American story. He even cobbled together an old comic strip proposal titled Starman Zero and made a Fighting American story. Nothing went to waste. When the owners of Crestwood caught Joe reusing a previous story and reworded it into a new story they responded angrily by withholding payment, further tightening up the cash flow. Now Jack and Joe’s contract with Crestwood never said anything about reusing existing art, but still Crestwood continued to hold back payment. In Nov. 1954, Joe contacted his accountant Bernard Gwirtzman who demanded a financial audit of all monies to be paid to S&K, as called for in their Young Romance contract. Crestwood was confident that their books were clean but when the auditors were finished, they presented Crestwood with a bill for 130 thousand dollars. The astonished owners threatened to close down the shop rather than pay the money. After some negotiations, they settled on a lump sum of 10 thousand dollars. The money helped stem the immediate cash outlay. The victory was nice, but the long term result was that the boys would get no new work from Prize for the next year, time that saw S&K reeling from the onslaught. An interesting aside, Joe says that the editor Reese Rosenfield was getting five percent of S&K’s royalty shares, for bringing them together. But after the attorneys finished their audit, they told Joe that Reese wasn’t protecting their shares, as he should have done as their agent. He suggested cutting Reese out of the money that Prize paid, which they did. It’s easy to figure this soured Kirby towards editors who demand a payback of the artist’s salary, but don’t follow through on their end.

Some retailers took it out on Leader News, and refused to carry any product from them–this included the Mainline books. Pretty soon, the advances from Leader News stopped and Mainline could no longer continue. Stories of artists not getting paid made the rounds. George Roussos remembered; “When some difficulties arose, a few artists weren’t paid. This caused a lot of resentment towards Joe and Jack, and they avoided them. I met Jack later at an art store at Grand Central Station. He was happy to see me, and I sensed he wanted to talk…. We covered every subject, only he did all the talking. I guess it was pent-up energy and he was rather hurt that people took out their anger on him-unnecessarily he felt.” Mainline left Leader News.

Stamped out

For perhaps the only time, Jack and Joe were on the outs. Roussos recalls; “I don’t know the extent of what really took place, but there was a point when they split up when we were working at Crestwood’ Joe took the business end of it and Jack would do the artwork. That didn’t work out very well, because when you split up two people in the same room…… I never dwelled into the business end; I just knew the superficial end. I knew the results of what happened, but I didn’t know what brought it about. I knew that they split up while in the same room because I was there. There were differences but I was never around when they had any particular argument.”

Soon, Leader News claimed bankruptcy and went completely out of business when EC Comics closed up the comic book division, leaving them with only Mad Magazine–which was not covered by the Comics Code Authority. The first Comics Code stamped book for Mainline were books cover dated Feb. 1955. They were the last published with the Mainline logo and Leader News blurb.

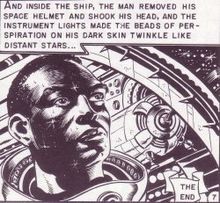

It’s hard to be exact about just how much the code affected the editorial content of the books. There are many silly examples of nitpicking and squeamishness of particular visuals-such as hands without weapons, reaction to unshown threats, and blacked out details. But I can recall only one rather sad and silly argument over content of a story. Despite the romance books delving into societal problems, there were two they would never touch; racial integration and gay lifestyles. S&K never ventured close to either. Interracial relationships or even positive slants on black life were understood to be forbidden. Bill Gaines of EC, shortly after the code was installed offered up a filler story for Incredible Science Fiction. The story, titled Judgment Day was drawn by veteran Joe Orlando, it dealt with a lone Earth astronaut judging whether a young world was ready to be admitted to the greater galaxy of worlds. The astronaut judged them ineligible because their society had been broken up by races with one race considered a lesser entity and treated as such. The irony was that when the astronaut returned to his ship, he took off his helmet revealing himself to be black. A rather positive story in that it showed man had overcome its darkest stain. Judge Murphy, the head of the comics code refused to allow it to be printed, despite the fact that the comics code never addressed racial interests. The story broke none of the listed no-nos of the code. The real insanity of the whole issue was this same story had originally been run three years earlier-pre-code- in the title Weird Fantasy to absolutely no blow back or even negative press from the Southern retailers.

Historian Digby Diehls notes in his article Tales From the Crypt, the Official Archives:

“This really made ’em go bananas in the Code czar’s office. ‘Judge Murphy was off his nut. He was really out to get us’, recalls [EC editor] Feldstein. ‘I went in there with this story and Murphy says, “It can’t be a Black man”. But … but that’s the whole point of the story!’ Feldstein sputtered. When Murphy continued to insist that the Black man had to go, Feldstein put it on the line. ‘Listen’, he told Murphy, ‘you’ve been riding us and making it impossible to put out anything at all because you guys just want us out of business’. [Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious [and] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy. ‘This is ridiculous!’ he bellowed. ‘I’m going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis, to do this. I’ll sue you’. Murphy made what he surely thought was a gracious concession. ‘All right. Just take off the beads of sweat’. At that, Gaines and Feldstein both went ballistic. ‘Fuck you!’ they shouted into the telephone in unison. Murphy hung up on them, but the story ran in its original form.”

Bill Gaines finally gave in and closed down the comic division, but would get the last laugh as the reconstituted Mad Magazine (code free) became one of the great publishing successes of the Twentieth Century.

To make matters worse, at the same time that Mainline folded, S&K were engaged in the legal mess with Prize Comics and work at Prize ended. Fighting American was cancelled after issue #7 and Black Magic after 33 issues. Black Magic’s end should not be dismissed so easily. It was in Black Magic that Jack first worked in a new genre that would play a huge role in his immediate future. It was also the launching point for new artists, like Steve Ditko.

The Fifties would see the rise of new style sci-fi films. With a background of a world divided by an Iron Curtain, man had created a force so strong that it dominated the world’s psyche. The anxieties as seen in the rise of Sen. Joe McCarthy, the fanned Cold War paranoia, the UFO phenomenon, and uncontrollable science found a new source of projection; the introduction of Post Atomic Science Fiction movies.

From The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction;

“It was films in this mould (Them, Invasion of the Body Snatchers) rather then the landmark Destination Moon (1950) and its sober celebration of man’s imminent conquest of space, that dominated the decade. Monsters from without and within–Hollywood and comics were investigated by the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities– threatened America, as often as not created or awakened by the bomb (as in The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, 1953) Nature rebelled and a variety of aliens, many of whom, like The Man From Planet X(1951) had peaceful intentions were received with hostility. A few films, like The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) and The 27th Day (1957) addressed themselves directly to the political implications of such anxieties, while others, notably War of the Worlds (1953) and When Worlds Collide (1951) had a religious dimension that saw it as a punishment for the catastrophes that befell man.”

TV leads the way

This same style science fiction mode was seen on TV with the new series Science Fiction Theater, produced by Ivan Tors. This was the first anthology devoted to the futuristic world of post-war fears. The series speculated on such things as visitors from other planets, UFO incidents, space fight, espionage… More technology, and miracle drugs that could cure all ills. It contained stories of crackpots; who turn out to be visionaries, and eyewitnesses to the fantastic, fighting to be believed; psychic phenomena straight out of a Reichian nightmare. The show also utilized experts as consultants to help keep the show within the known realm of the scientific possibilities speculated at the time. The show did not last long, but it did lead to even better followers like Twilight Zone, and Outer Limits.

Instead of the old Gothic horrors of Dracula, and the Werewolf, the new films centered on run amok science creating mutates, and allegorical visitation of alien species. Things that didn’t seem so farfetched when viewed thru a current prism. The Thing, The Day The Earth Stood Still, Them, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers were big hits. And comics always followed the big hits. “The monster phenomenon got started primarily just because people were concerned about science,” Kirby recalled. “People were concerned about radiation and what would happen to animals and people who were exposed to that kind of thing.” Their fears had been awakened at Roswell.

The movie that launched a 1000 comics

Though the sci-fi movies were definitely an inspiration, the author feels the genre change can be traced back to the radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, in 1939 by Orson Wells and the paranoid reaction to a sci-fi subject as well as the sci-real atomic bomb.

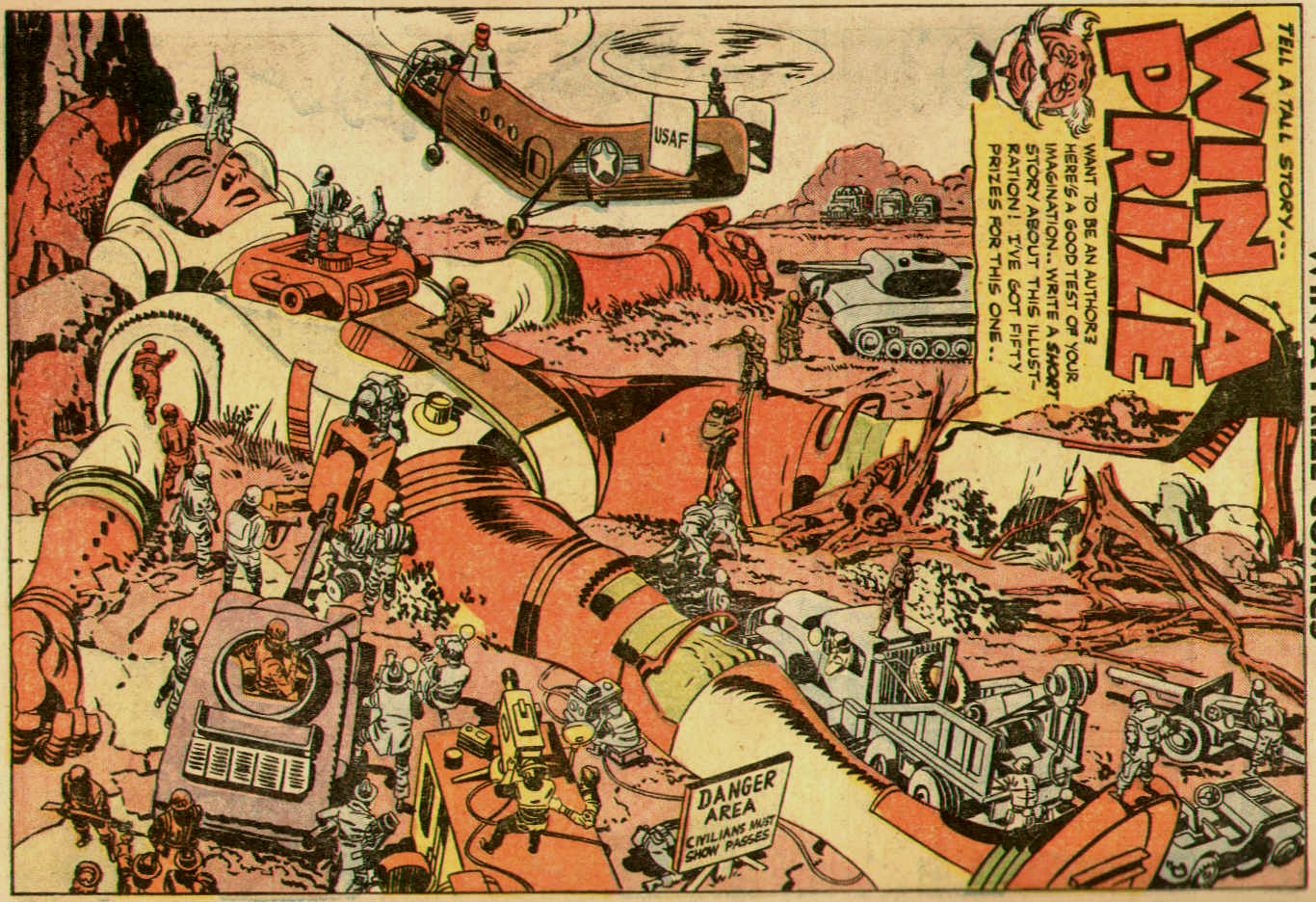

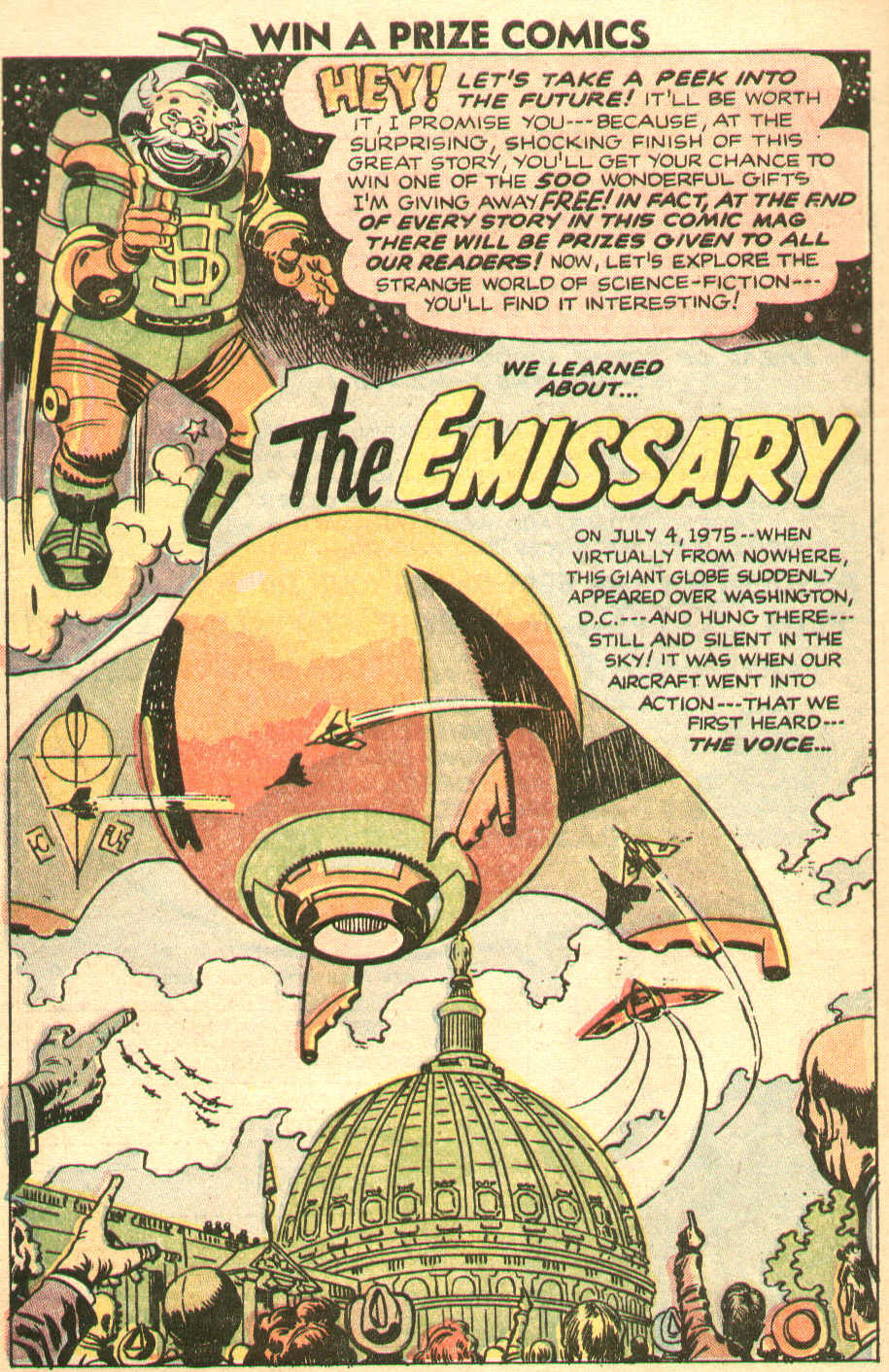

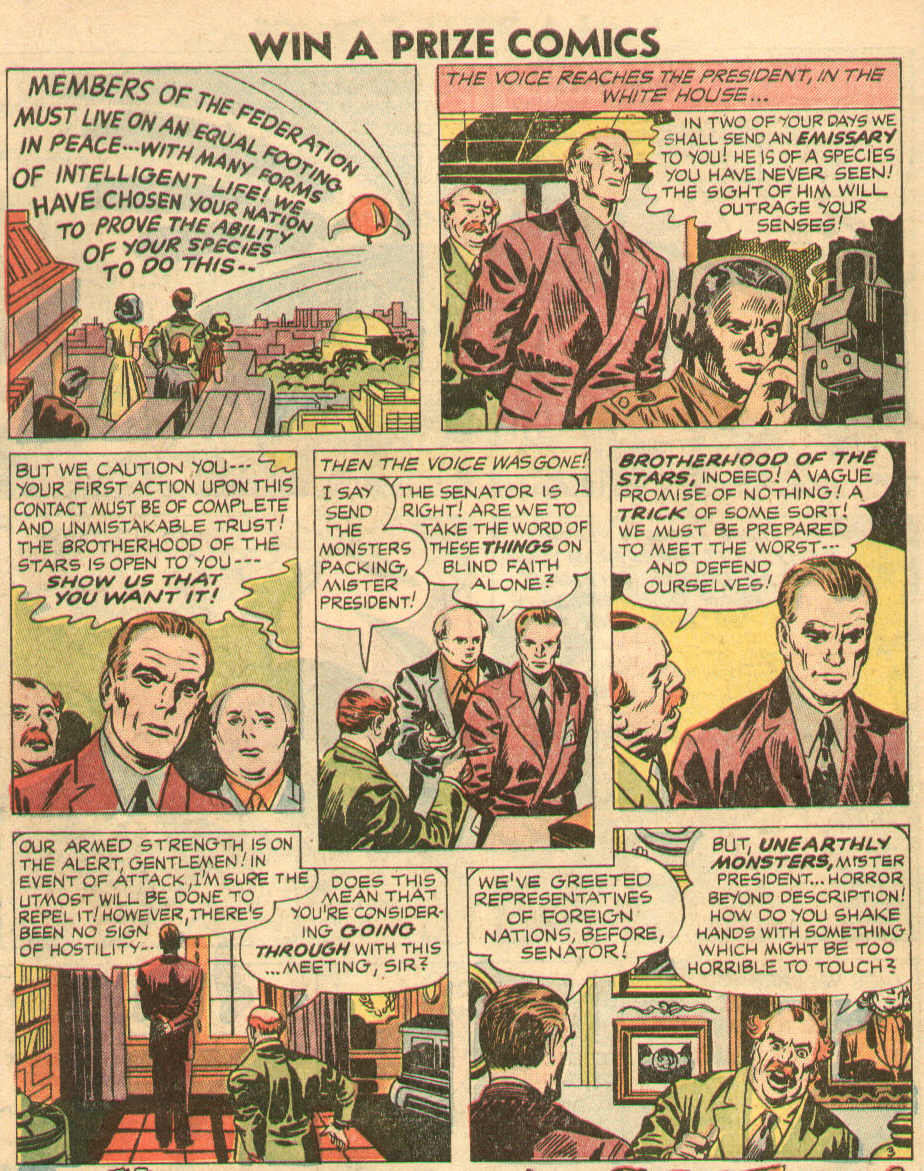

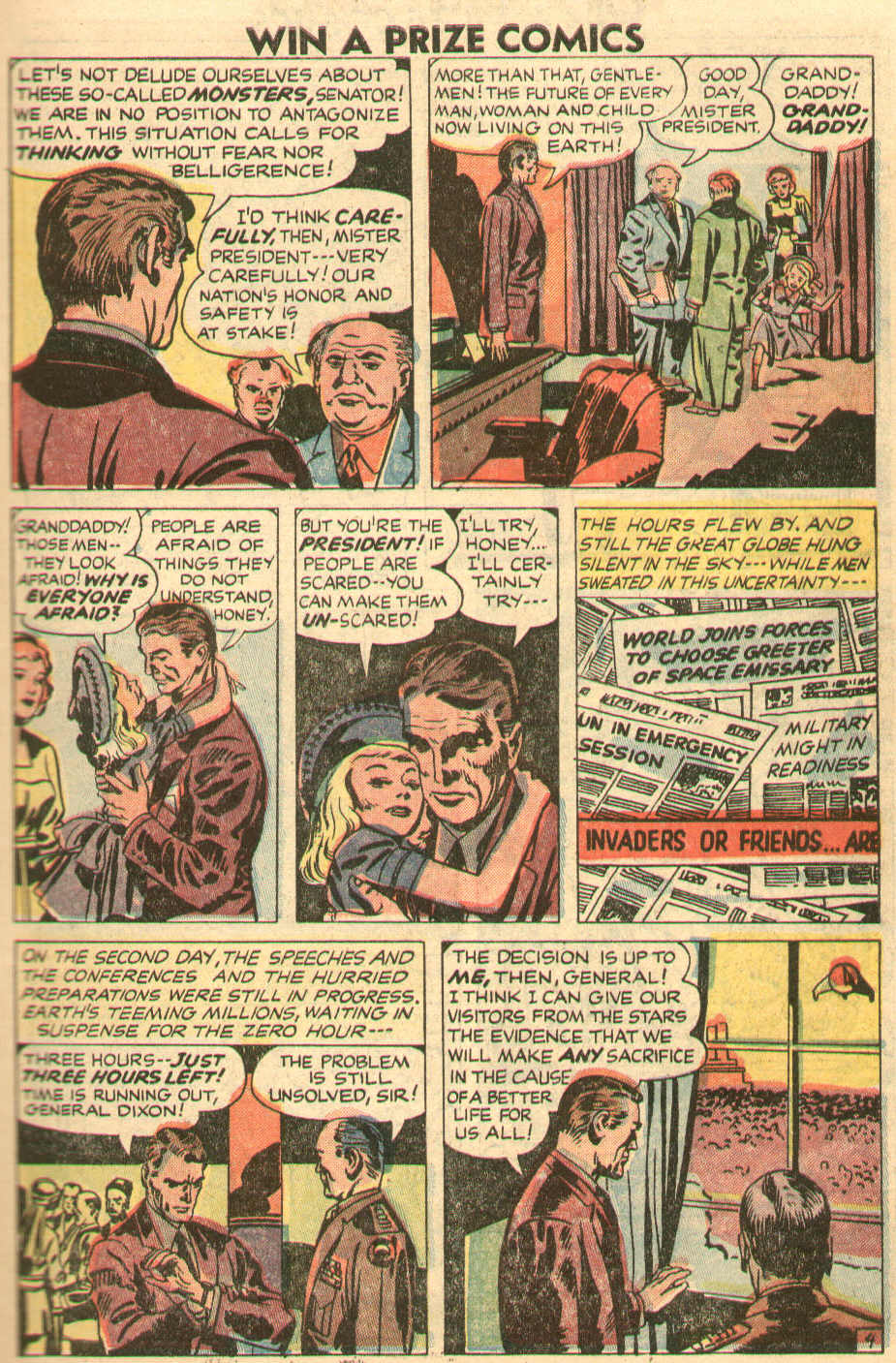

Jack and Joe always loved sci-fi and the sci-fi movies, and incorporated themes into their stories. The newly formed CCA also prohibited much of the Gothic horror traditions. The next to last S&K Black Magic issue cover featured a strange monster very similar to the fantastic “intellectual carrot” of The Thing, as portrayed by James Arness. The last S&K story in Black Magic centered on, and was narrated by a shark mutated by atomic radiation to the point of sentience. The story Lone Shark was a chilling tale of run amok science and the unforeseen consequences of atomic energy plants and the dumping of atomic waste. There is also an unpublished Black Magic cover featuring a burnt out wasteland with alien scientists in hazmat gear and Geiger Counters checking out the charred remains while a huge mutated creature hovers in the background. In Win-A-Prize #1(Feb. 1955) published by Charlton, Jack drew a wonderful allegorical tale of the first visitation from space and the inherent fear and paranoia in the human reaction. This genre so resonated with Jack, it was said that Jack hoarded reams of science fiction magazines and pamphlets, and when he died, the garage was full of them. Jack was always at his best when his stories had a sci-fi basis. Joe would recall that Jack was “the pulp man-he used to read all of them, especially the sci-fi ones.” Jack would even insert sci-fi scenarios into other genres like western stories, such as a Bullseye story set in a lost prehistoric wasteland populated with pterodactyls, or a land based Fighting American trapped in a deep space dream.

Joe, reeling from the failure of Mainline, still had faith in the books, and took them over to Charlton Comics, an independent company that distributed their own product. Charlton was started by two ex-convicts named John Santangelo and Edward Levy. Santangelo was an Italian immigrant who worked as a brick layer and masonry contractor. He first began publishing unauthorized lyrics to famous songs (for his soon to be wife) and made enough to quit his job. He would discover the hard way that America had copyright laws and would end up in the slammer. While there he met Edward Levy who was a disbarred attorney who was involved in a billing scandal. The two became friends, got out of prison at roughly the same time and made a handshake deal to go into legit publishing together.

The original logo – an early Charlton attempt at an educational book

Edward was able to get the rights to publish lyrics legally and John would hire people and handle the publishing aspect. The company would buy an old printing press that was typically used to print cereal boxes and would also set up their own distribution network. This made Charlton Comics quite unique as they were very much a “done in one” publisher. They did everything from buying the paper to print on, hiring the people to create the magazines, to delivering the magazines to the newsstands. But like any printing presses, it cost a lot of money to not have the presses rolling. It’s very likely that they got into comic books as a way to print something in between their magazine runs. No doubt they probably also recognized the popularity of comic books and were hoping to cash in. Based in Derby, Connecticut, Charlton was known as a low rent business that paid the lowest page rates, and whose quality control was the worst in the business. It was also known for having a very loose editorial policy that left the artists alone.

Comic by Edward Levy, the indicia soon read Charlton – New S&K at Carlton

Joe recalls, “Charlton was the last port of call for a publishing enterprise on the verge of going under. Santangelo and company were usually willing to continue publication of failing magazines or comic books, taking over the printing, engraving, and distribution at their own plant….and eventually taking over, period.

“When Leader News, our Mainline Publications distributor had failed, Jack Kirby and I turned to Charlton as a last opportunity to continue publishing our line of comic books. We made frequent trips to their plant in Connecticut where the highlight of the day was a tasty Italian lunch at the executive table of the employee’s spacious cafeteria. When the noon whistle blew, the printing crew, mostly Italian immigrants who spoke little or no English, gulped down a hasty sandwich and then retired to an adjacent construction site where they picked up their masonry tools and continued putting up new buildings, a project that seemed endless. After the lunch hour, the men returned to the printing shop to resume their regular work. Kirby and I made a small living at Charlton for a couple years and then went the way of other patrons. Out.

Joe’s memory is somewhat faulty; S&K Charlton work only lasted less than one year. What was never explained was why Joe didn’t take the Mainline titles to Crestwood, or Harvey. Joe decided to chuck the brushes and head to advertising.

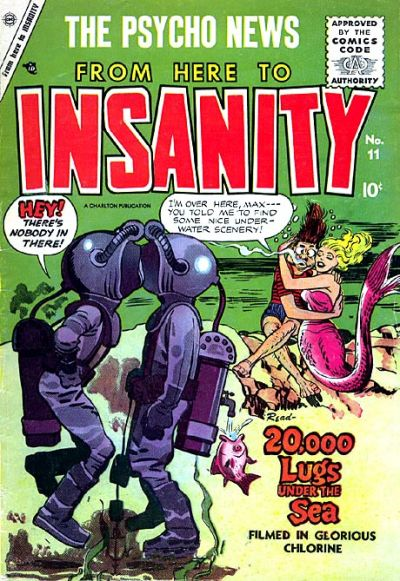

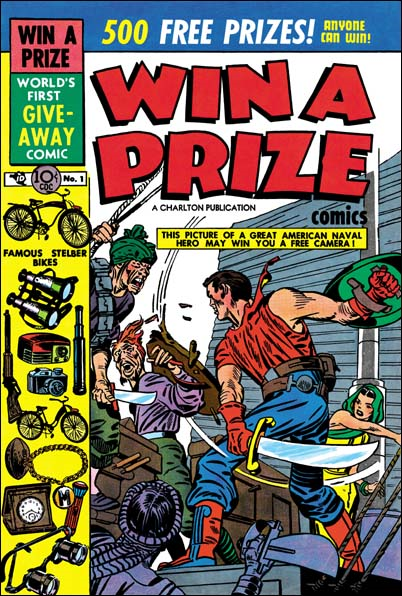

The problems of Leader News and some other small distributors left a gaping hole, which Charlton was glad to fill. In 1954, Charlton went shopping, picking up the low hanging fruit. Besides Mainline, they also picked up titles from Superior, St. John, and Fawcett Publications. Besides the four Mainline titles, S&K also produced a new title called Win-A-Prize. This odd anthology title was an amalgam comic book and prize catalog with prizes awarded for all types of contests and reader contributions mixed in with some surprisingly good comic tales. Only two issues were published. They also produced one issue of From Here To Insanity, a humor title in the Mad Magazine vein.

Back to humor and parody

Joe and Jack produced two final issues of each of the four Mainline titles for Charlton before closing down the studio for good. It was a sad ending to the greatest team of comic creators ever seen. Fifteen years of unparalleled innovation and entertainment ending as collateral damage of the social wars fighting for the souls of our youth. Jack recalls those years fondly “It was a wonderful time to work in the field-if you neglect the financial problems. I wouldn’t class the fifties as the greatest period in comics–it was, to be frank, a really ugly period. Ugly clothes, cars, people. But it was a time when the most productive people in comics were still in the field. Marvin Stein was with us-he was a first rate man and one of the best artists we had. Mort Meskin was at his height. Steve Ditko was blossoming out and doing fine work. There were still writers and artists around….Good ones. It was certainly akin to working a Renaissance period.

The age of post-atomic comics had begun.

The cause of freedom does not run smooth, often it feels like a one step forward, two steps back proposition. But occasionally a big step happens that can never be walked back. On May 14, 1954, in a historic decision, the Supreme Court in one fell swoop ended the decades long tyranny of the Jim Crow laws. Plessy v Ferguson was no more. Thurgood Marshall, a Baltimore lawyer convinced the high court that separate could never be equal, and all people were in society together. Clashes became more frequent as State governments attempted to stop black students from public education, and forced the Federal branch to enforced the new equal education standards. Suddenly public faces like Orval Faubus, Bull Mongomery, and George Wallace showed the world what had once been the dark secret of Southern life. But the dark underbelly remained.

September of ’55 found the country’s attention riveted to the small backwater town of Money, Mississippi. A body had been fished out of the brackish Tallahatchie River. A black body beaten and decomposed so badly that identification was made by way of an initial ring on one of his fingers. The body was identified as that of Emmett Till, a 14 year-old black Chicago boy who was visiting relatives in Mississippi for the summer. The last thing his mother told him before putting him on the bus was that in the South black people had to act different to the white folks and if they tell him to bow and scrape, then he better bow and scrape and look happy doing it.

with his mom in happier days

One day Emmett was playing with his friends and was bragging about how in Chicago he played with white kids, and in fact, he had a white girl friend. His friends oohed and ahhed, and challenged him to go inside and speak up the young white girl behind the counter. Emmett was up to any challenge and went inside, bought a piece of candy and as he left he flirted with the girl. The friends were agog, but there was no immediate response. No one thought anything about it until three nights later Roy Bryant, the owner of the store, and J.W. Milam, his brother-in-law, broke into Emmett’s Uncle’s house and drove off with Emmett. The young girl was Roy Bryant’s new wife, and in Mississippi, no black boy could talk fresh to a young white girl without punishment.

They drove Emmett out to the riverside and brutally beat him, crushing in his head and gouging one eye completely out. After one last act of defiance—or stupidity—Roy Bryant shot young Emmett in the head. They bound his body in barbed wire, weighted him down with a gin mill fan and dumped him in the river.

The body was fished out three days later, and subsequently identified as that of Emmett Till, who had been reported abducted three days earlier by his Uncle. Bryant and Milam were quickly arrested for murder and the stunned nation was in an uproar. The young boy was quickly made into a martyr for the Civil Rights movement and the Northern press berated the South and its Jim Crow ways unmercifully. At first even the local townsfolk were aghast at the crime and neither Bryant nor Milam could get legal representation, but as the press storm continued, the Mississippians began fighting back. Suddenly the defendants had lawyers fighting to represent them.

The defense’s case was based on the problems with identifying the body, that no one could be sure if the body was that of Emmett Till—despite the initialed ring on his hand. But the defense theory was really a ruse. They knew that the all-white jurors wanted to free the two men, but they needed something—anything to which they could hang their case. Defense attorney John C. Whitten told the jurors in his closing statement, “Your fathers will turn over in their graves if [Milam and Bryant are found guilty] and I’m sure that every last Anglo-Saxon one of you has the courage to free these men in the face of that [outside] pressure.” The poor condition of the the body was enough of a straw to grasp and after just an hours deliberation, they found the men innocent.

His mother moaned; “Have you ever sent a loved son on vacation and had him returned to you in a pine box, so horribly battered and water-logged that someone needs to tell you this sickening sight is your son“

The Northern press and black leaders were aghast at the decision and quickly mobilized protests, and civil rights volunteers quickly spread around the area trying to calm the black workers of the area. They knew one thing, and that is that one incident like this was bad, but worse, it emboldened other white racists to imitate their actions knowing that they were immune to prosecution. Nothing scared the black populace more than the idea of copycat murders. One lynching usually led to three, four, or more similar occurrences. It was like a bad weed, pull one, and a dozen more sprout up. Every redneck with a grudge now had an avenue to vent his frustrations and bile.

It had been a while since the Civil Rights movement had such a noteworthy face to put on prejudice and injustice. Emmett’s age and Chicago roots were just the ingredient needed to rile up the millions of blacks who had fled the South and remind them that Southern blacks were their brothers. For the first time, northern blacks saw that violence against blacks in the South could affect them in the North. In Mamie Bradley’s words, “Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something happened to the Negroes in the South I said, `That’s their business, not mine.’ Now I know how wrong. I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all.” Blacks, in the North as well as in the South, would not easily forget the murder of Emmett Till.

Just as Leo Frank’s murder had united Jews against bigotry and prejudice, Emmett Till became the brutalized face of the Black movement demanding their rights. 1955 would be just the first of many a long hot summer in the U.S.

Far too often these singular acts of evil soon fade and blow away, overshadowed by new problems and events but Emmett’s blood seeped into the soil and gave root to a whole spectrum of new offshoots. In Montgomery Alabama, the new Pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became galvanized to avenge this slaughter and change this country. He started to talk out and preach a whole new strategy of love and non-violence aimed at changing the tone of the country. A young black woman on her way home from work refused to give up her seat on the bus and was summarily arrested for civil disobedience. Rosa Parks was outraged by young Emmett’s death and had joined the local Montgomery NAACP; she had attended talks given by this new young Pastor and had decided enough was enough. Following her arrest, a new policy of striking back took place when Dr. King organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The strike went nationwide and suddenly the black populace had a voice. The eyes of the nation focused on this problem and the violence and led the Court to overturn Alabama’s cruel Jim Crow laws.

A young black man, newly recruited to the Black Muslim crusade, was transformed by Emmett’s death. In prison for rape, the Oakland Ca. native fed his reactionary furor. Two days after discovering the tragedy of young Emmett Till, Eldridge Cleaver had a “nervous breakdown” and “began to look at America through new eyes.” Always entranced by white women, his attitude toward white women changed radically, he suggested. “Somehow I arrived at the conclusion, that as a matter of principle, it was of paramount importance for me to have an antagonistic, ruthless attitude toward white women.”

Using this outrage as a recruiting tool, the Nation of Islam grew from 15 temples in 1955, to over 40 in 1960. The small radical violent offshoot of the Islam religion soon became a large militant alternative for blacks who had grown tired of never fighting back.

Another young revolutionary used Emmett Till’s death as a launching pin to unite the black populace in the cause of Islam. Malcolm X would become perhaps the most feared and famous black leader of the late 50’s and early 60’s; only Martin Luther King came close.

In Louisville, Kentucky a young 15 year old boy playing with some friends saw a newspaper with the story of Emmett Till’s death; complete with the horrid picture of the mutilated body in the open coffin. The young black boy was not a novice to Southern reality, but this new abomination steeled a new radicalism and resolve into his hardening heart.

“Emmett Till and I were about the same age. A week after he was murdered… I stood on the corner with a gang of boys, looking at pictures of him in the black newspapers and magazines. In one, he was laughing and happy. In the other, his head was swollen and bashed in, his eyes bulging out of their sockets and his mouth twisted and broken. His mother had done a bold thing. She refused to let him be buried until hundreds of thousands marched past his open casket in Chicago and looked down at his mutilated body. [I] felt a deep kinship to him when I learned he was born the same year and day I was. My father talked about it at night and dramatized the crime. I couldn’t get Emmett out of my mind…” – Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali)

A somewhat younger southern boy responded differently, seeing this as a learning experience and life warning.

“It was Monday morning when my family got the word about the death of Emmett Till. I was barely two years younger than he and in the South for one of the first times that I was old enough to remember. My mother was particularly disturbed by the incident and spent most of the morning counseling me on “being careful,” a non-specific term which at the time I took to mean watching out for traffic on unfamiliar country roads….

On subsequent trips to the region I was “more careful.” I was also more apprehensive about being there. I was never sure what to do when in contact with Southern whites, and therefore I tried as much as possible never to make such contacts. My personal experience and the story of Emmett Till, which I read in great and gory detail upon my return North, served to confirm my notion that the South and its white people were different and dangerous…. I wondered if I would ever understand these people and their society. The need to understand encouraged my graduate study of Southern history…” – James Horton (historian)

Despite warnings from friends that talking out could hurt his career and legacy, Superstar Jackie Robinson replied; “If I had to choose tomorrow between the Baseball Hall of Fame and full citizenship for my people I would choose full citizenship time and again.” Jackie would begin circling the South giving speeches and voicing his concerns. His popularity was such that he even outsold Dr. King as civil rights speaker.

Perhaps cynically, some have suggested that this event was perfect for the new medium of TV. For the first time, nationwide news stations sent mobile teams to cover a local story. The name Emmett Till became known from New England to California’s sunny shore.

The Civil Rights movement finally had a moment that transformed the whole black population, and with it, the nation.

Previous – 12. Ghosts In The Attic | top | Next – 14. The Art Of The Swipe

Stan is incorrect when he states “so when S&K did their own romance book, then Prize took them off Young Romance and Young Love” and other similar comments that the publisher Prize cut back Simon & Kirby work when they found out about Mainline. Simon and Kirby were still listed as the editors in the required postal statement. Further Joe Simon’s collection included (before it was dispersed after his death) original and production art for the Prize romance titles. As for the Prize crime titles Joe and Jack stopped working on them long before they started Mainline. Jack’s absence from the Prize romance and horror titles was simply that he was too busy with Fighting American, Win a Prize (for Charlton) and Mainline. These titles were still produced by Simon and Kirby using mostly artists that had previously worked for them. When Kirby did actual penciling for Prize comics it was always a means of making some money in addition to his share of profits from producing the comics with Joe.