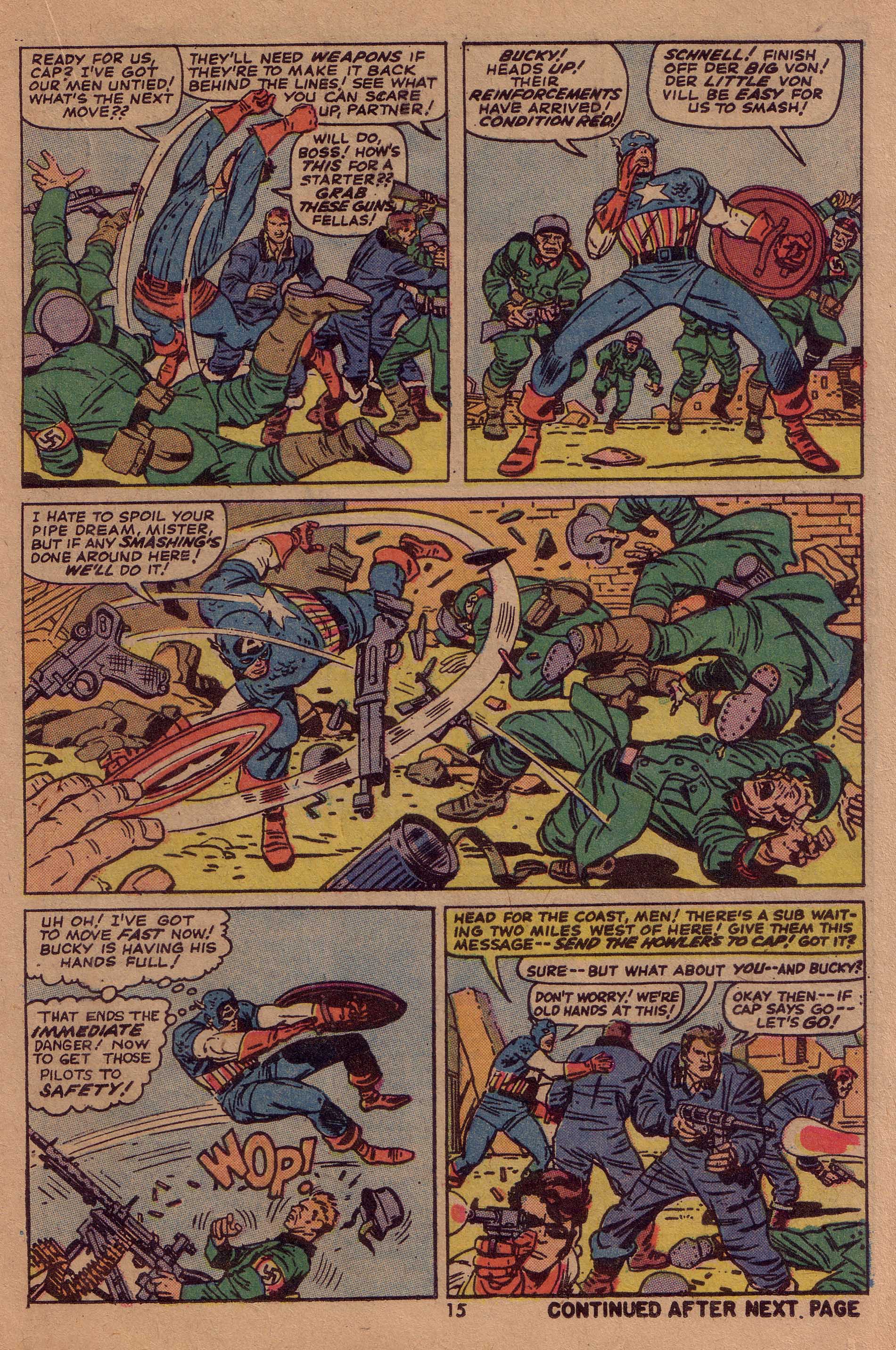

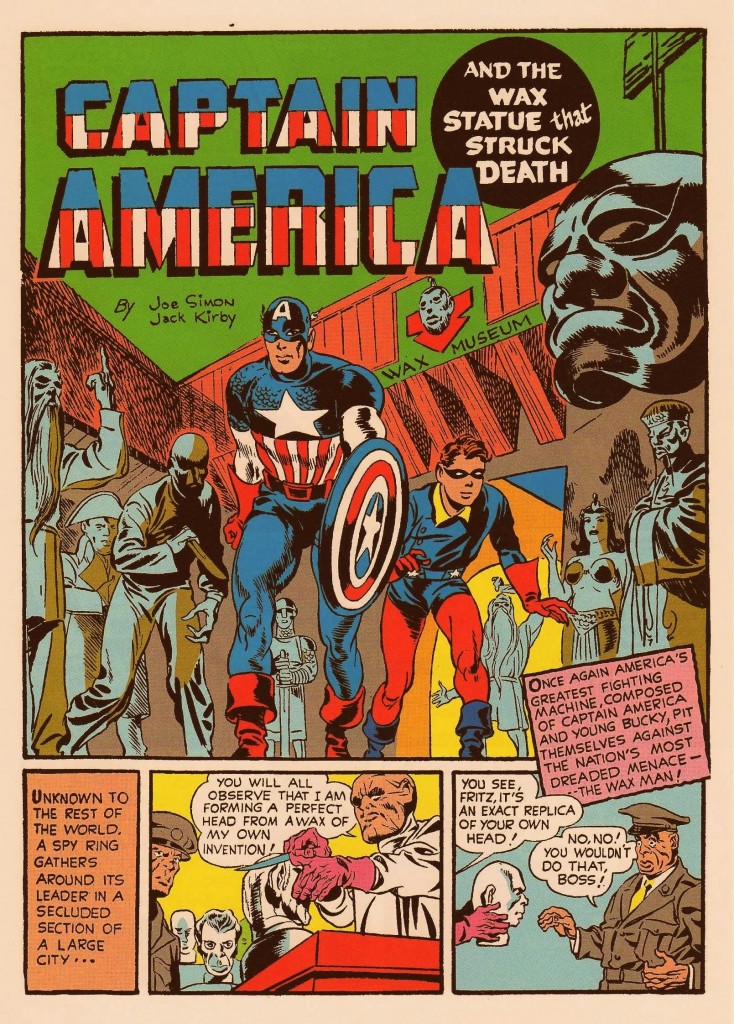

I finally broke down and borrowed the Avengers movie from my local library, so I essentially wasn’t making Marvel/Disney any richer. After all of the hype about how good the movie was, I was left pretty cold by it. It didn’t suck, but it seemed overrated. The Avengers starts slowly and takes some time to get off the ground. Much of the early action is dark and murky, taking place at night. The action towards the ending is of a fairly high quality but I have to say that I’m a bit burned out on this sort of thing. My favorite actor in the film is certainly Chris Evans’ Captain America, who projects a certain purity and earnestness that is very appealing. He has a nice bit on top of a car, repelling aliens, which is quite Kirby-esque. (shown below)

The cinematographer often uses the King’s forced perspective trick by having much of the action coming out of the screen and towards the viewer. Robert Downey’s Iron Man is also an amusing characterization and Tom Hiddleston’s Loki is appropriately sinister.

Anyway, it got me thinking about such films in general, particularly those based on characters created and animated by Jack Kirby. The King worked briefly in animation at the start of his career, and his work has always displayed a strong cinematic edge. In a quote from a May, 2008 NY Times editorial, Kirby explained,

“It’s kind of a John Henry concept where you have to compete with the camera, and, of course, you’re bound to lose because your medium is much more limited — it just hasn’t got the scope of the camera.’’

As the article continues, the editorialist, Brent Staples disagrees. “I hate to dispute The King, but I flatly disagree. Even the best of the movies reach moments where the action stops and the characters have to stand still, essentially doing nothing. On film, they often go dead, like so many dolls in a toy store window. In a Kirby comic, even when standing stock still, they would be radiating an intensity that film cannot convey.”

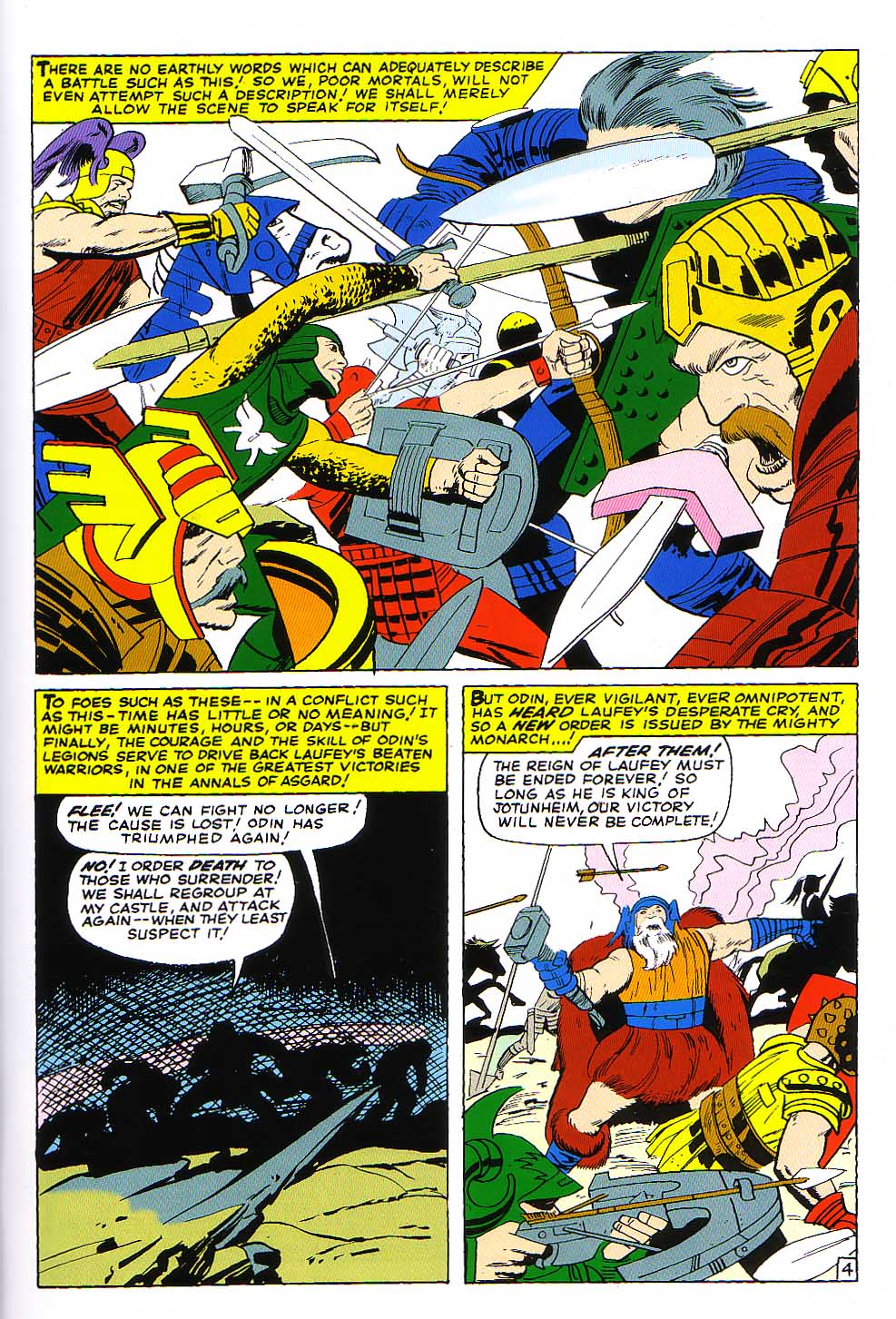

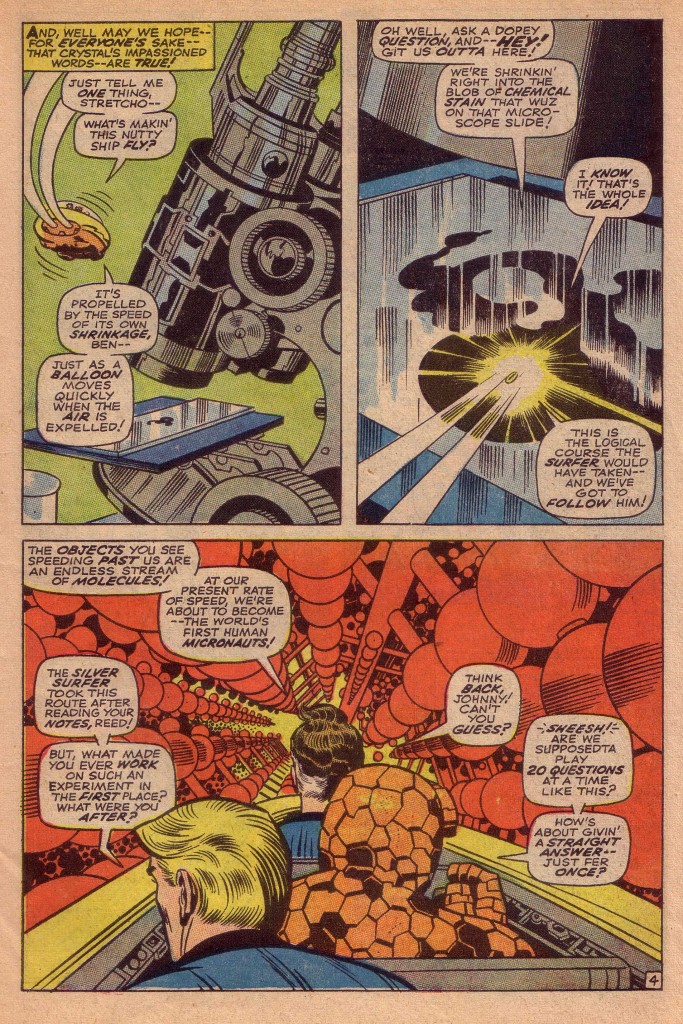

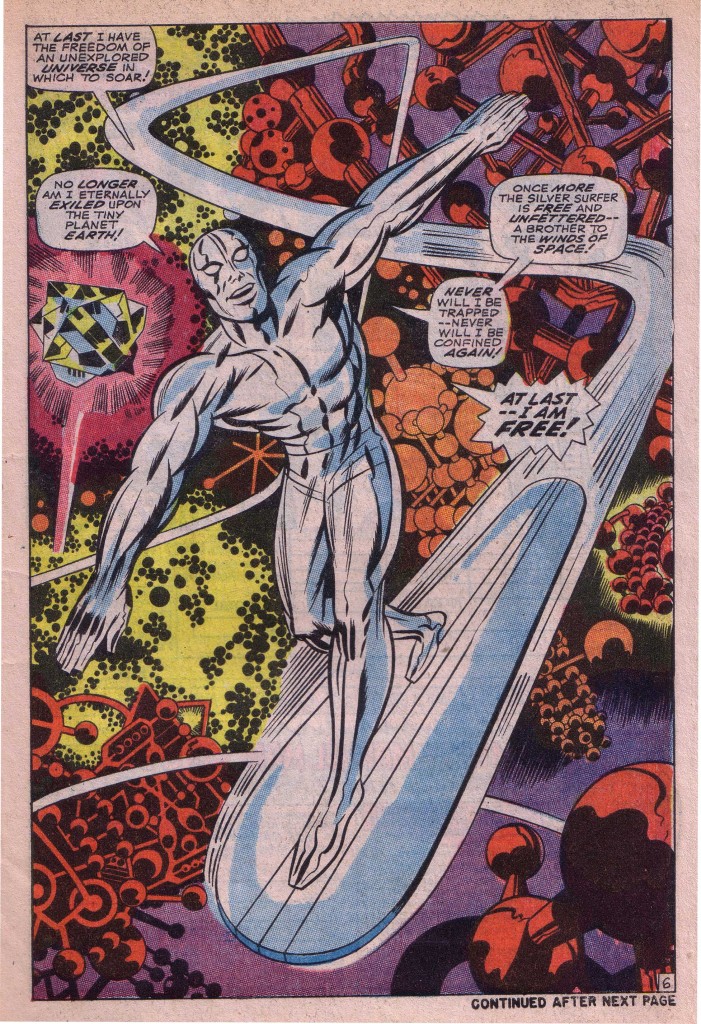

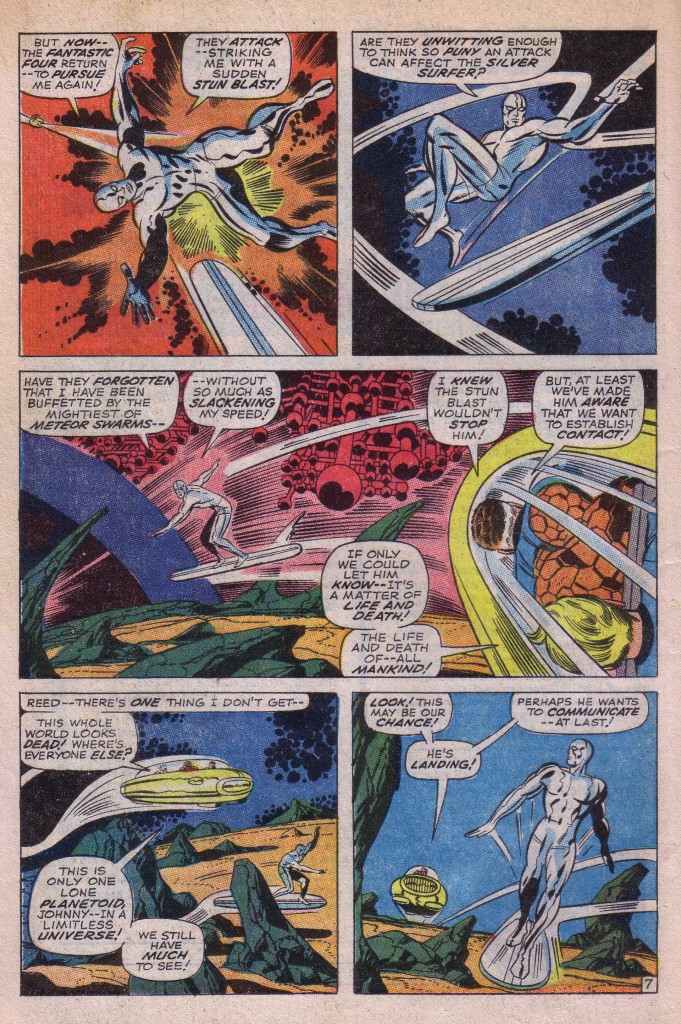

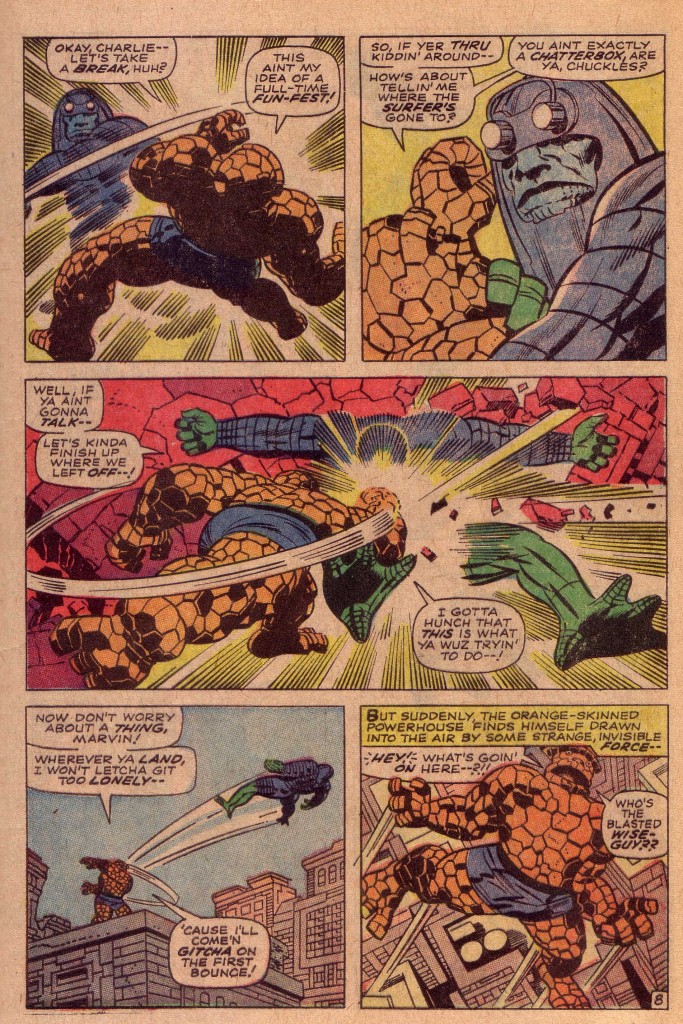

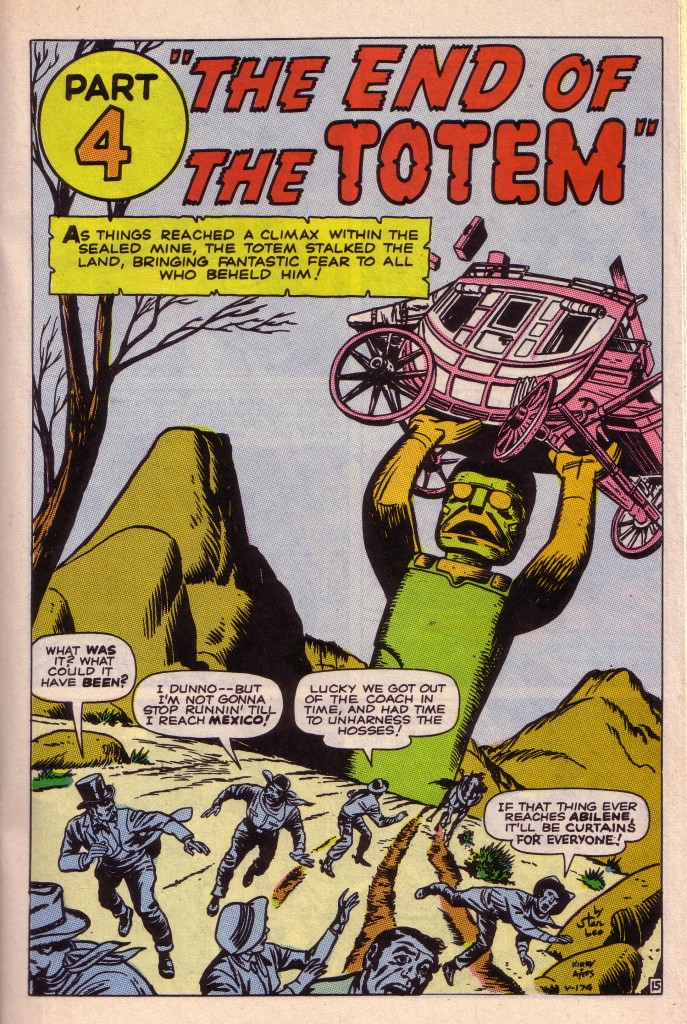

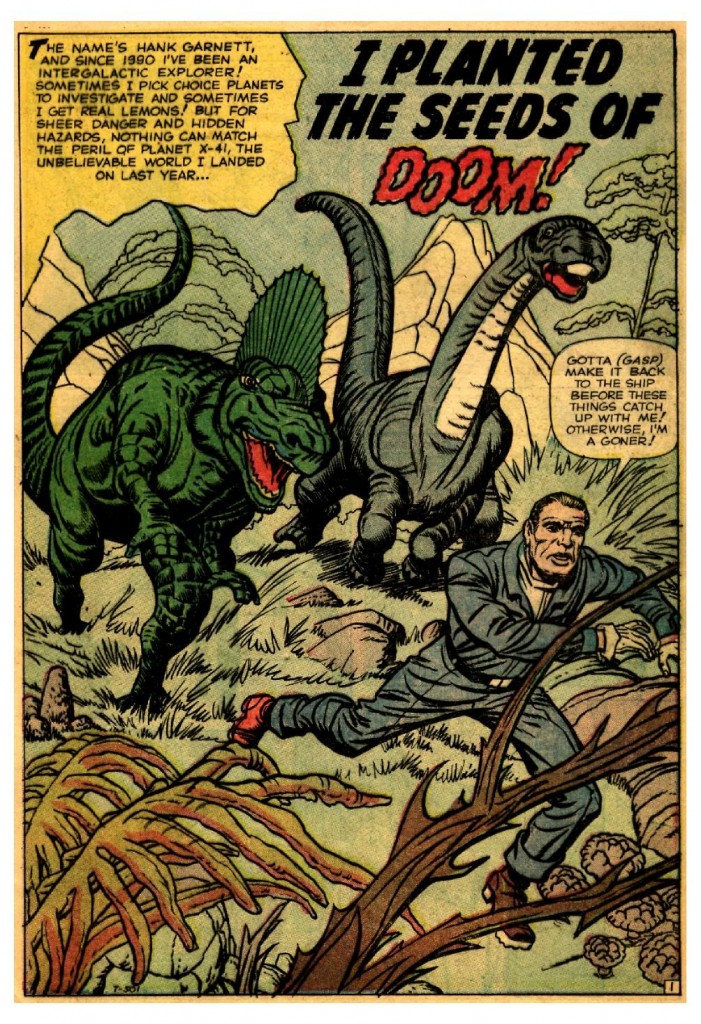

And this is certainly the case if we compare even the best superhero movie with a Kirby comic. Kirby’s mastery is in the ability to find the peak moment of action as well, which is also why one of his panels is often more dynamic than a live action sequence. When one sees for example, a power hitter connect for a home run, there is a moment where that swing is at its most forceful kinetically, but we are seldom ever able to see that fraction of a second. Kirby not only isolates it, he also amplifies it by exaggerating various aspects of human anatomy and perspective. That said, director Joss Whedon does an excellent job with action sequences in the movie.

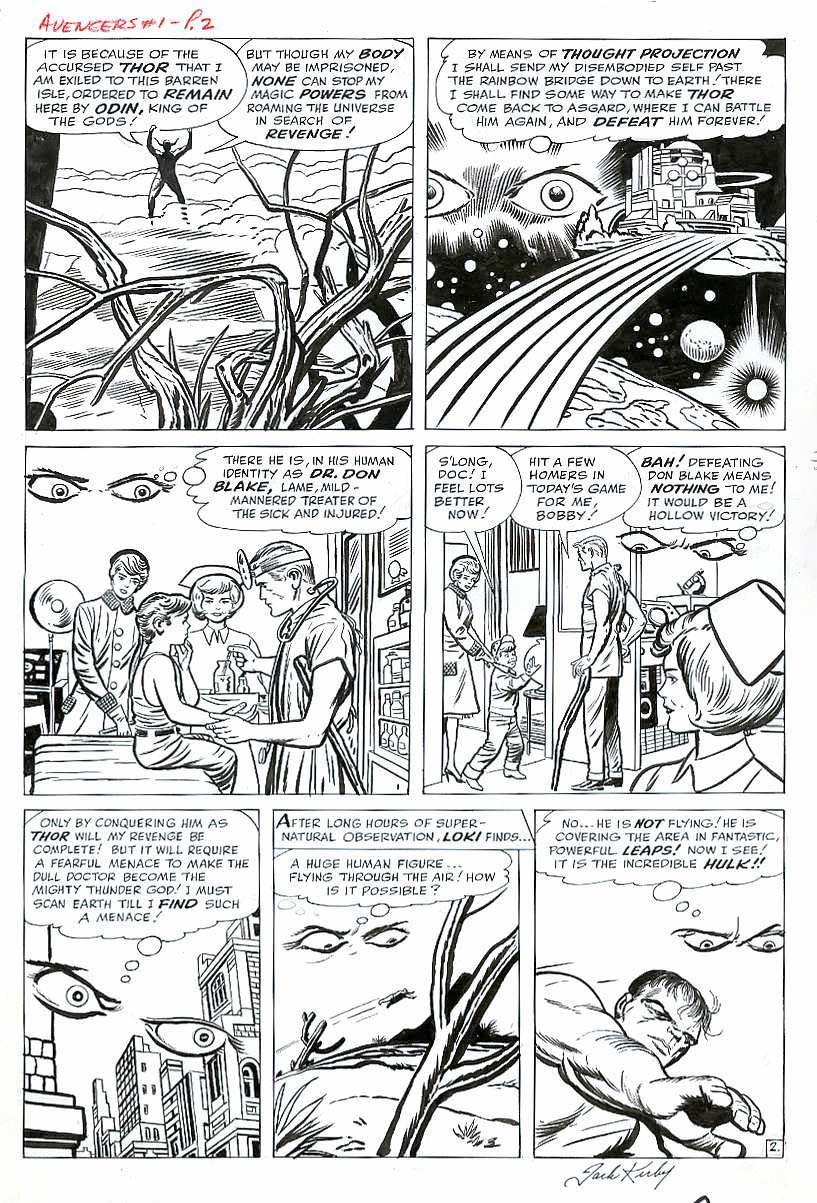

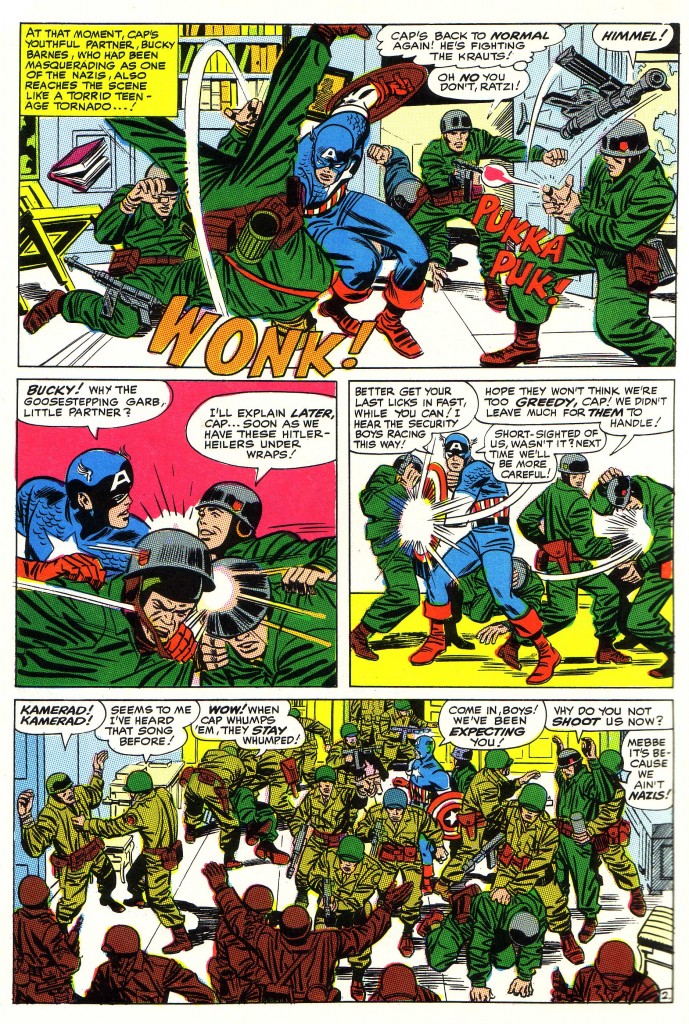

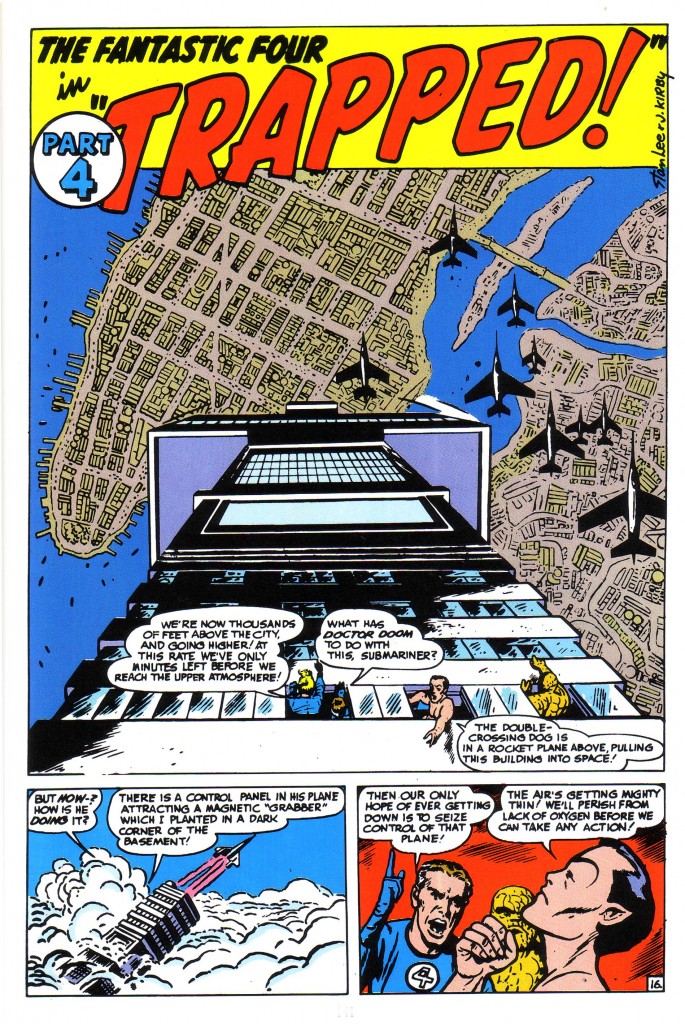

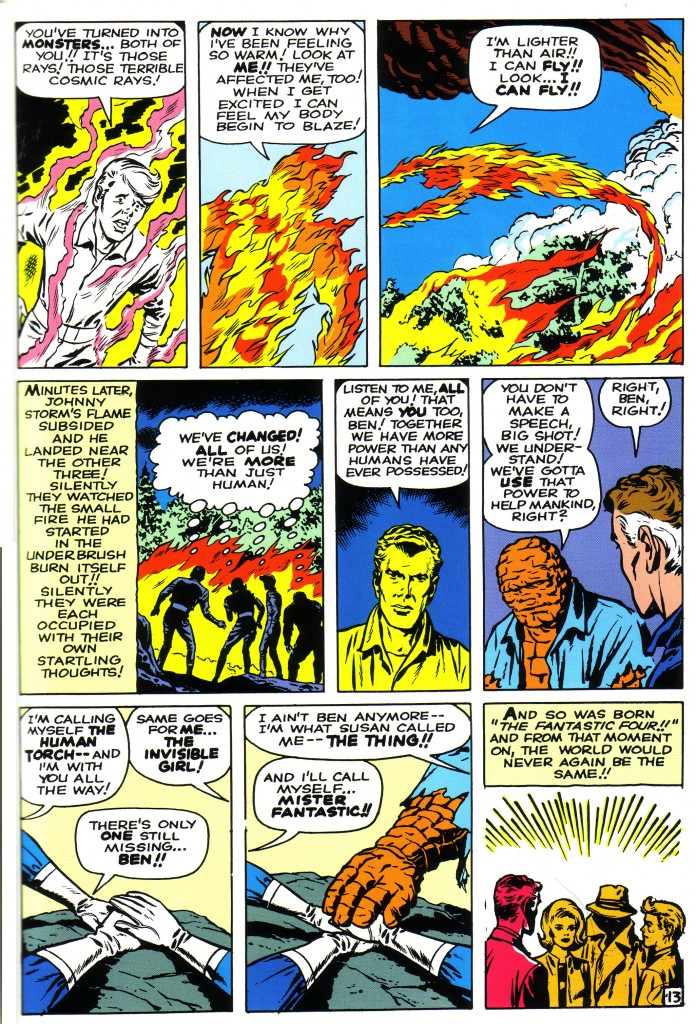

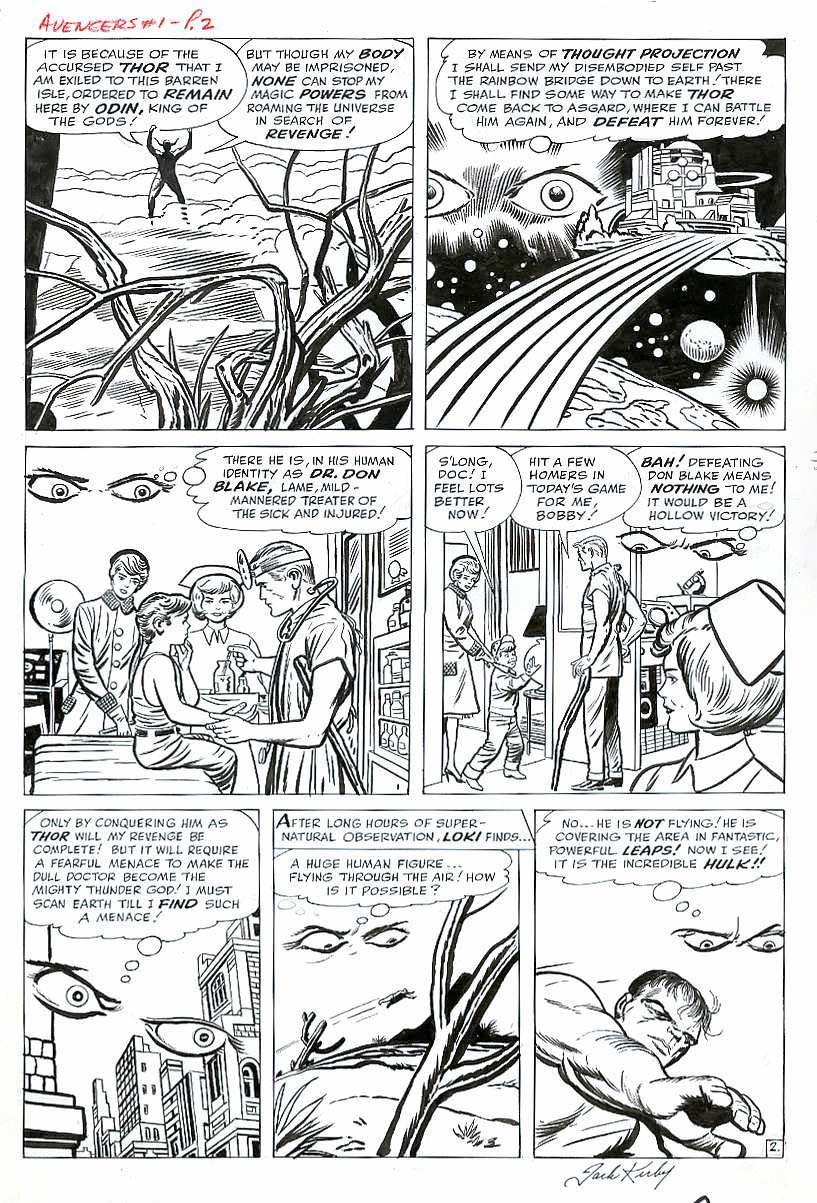

The Avengers film is more or less an updated version of Avengers #1, published in 1963. Basically, the Avengers come together in order to foil a scheme hatched by the insidious Loki. In the film, Loki enlists the aid of some nasty aliens, whereas in the comic he merely manipulates the Hulk and the Avengers into battle with one another, wherein they eventually team up to defeat him. Here, we see page two of the first issue, where Loki tracks the Hulk’s whereabouts as his evil scheme solidifies.

Kirby gives us a fantastic view of Asgard through Loki’s roving eyes, which eventually make their way to earth and finally settle on the airborne Hulk. Kirby is the comic book equivalent of the consummate film editor as he weaves his story with masterful panel transitions, and I’ve seldom seen a movie that uses space and time so effectively as his comic art does.

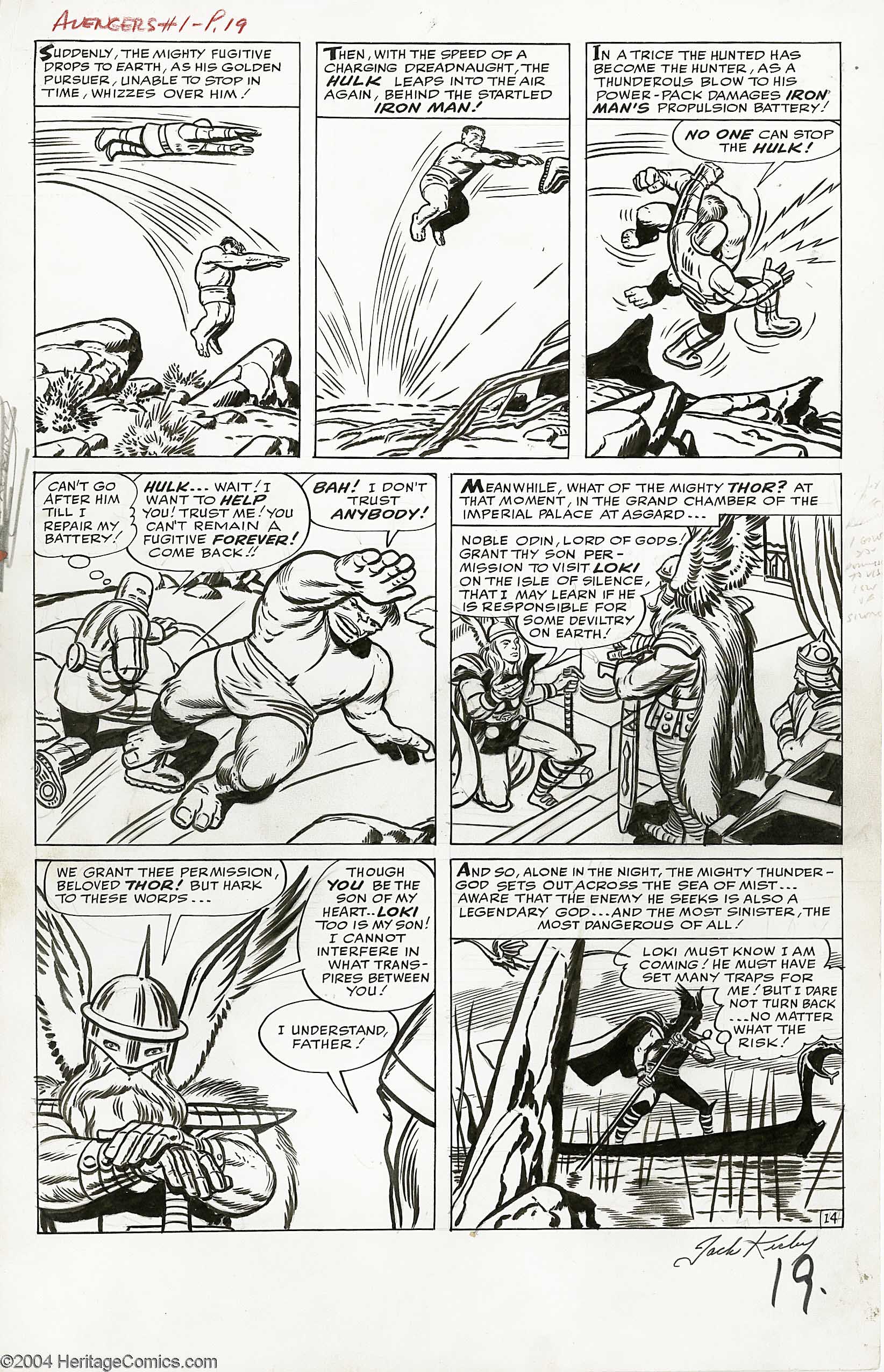

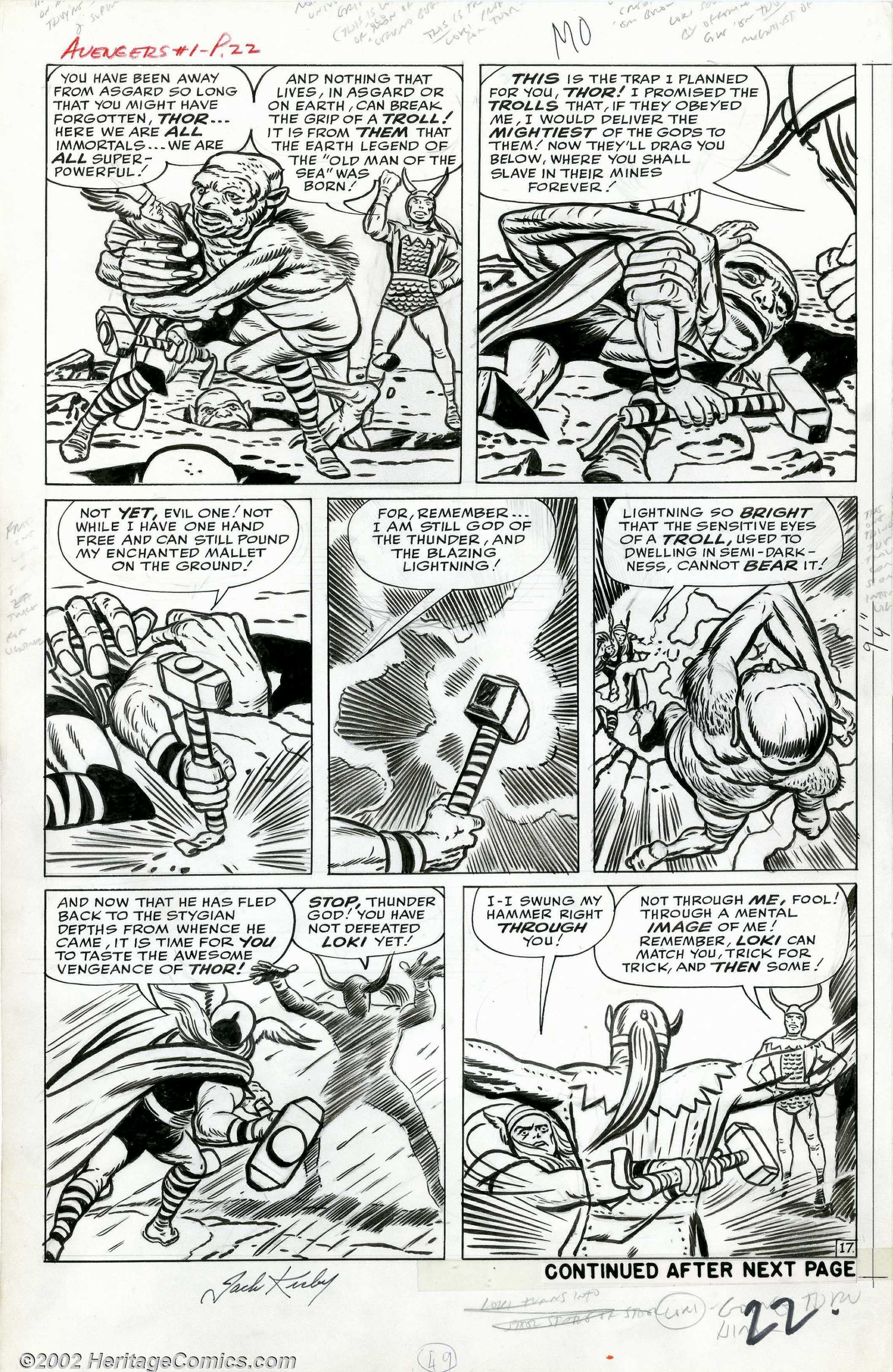

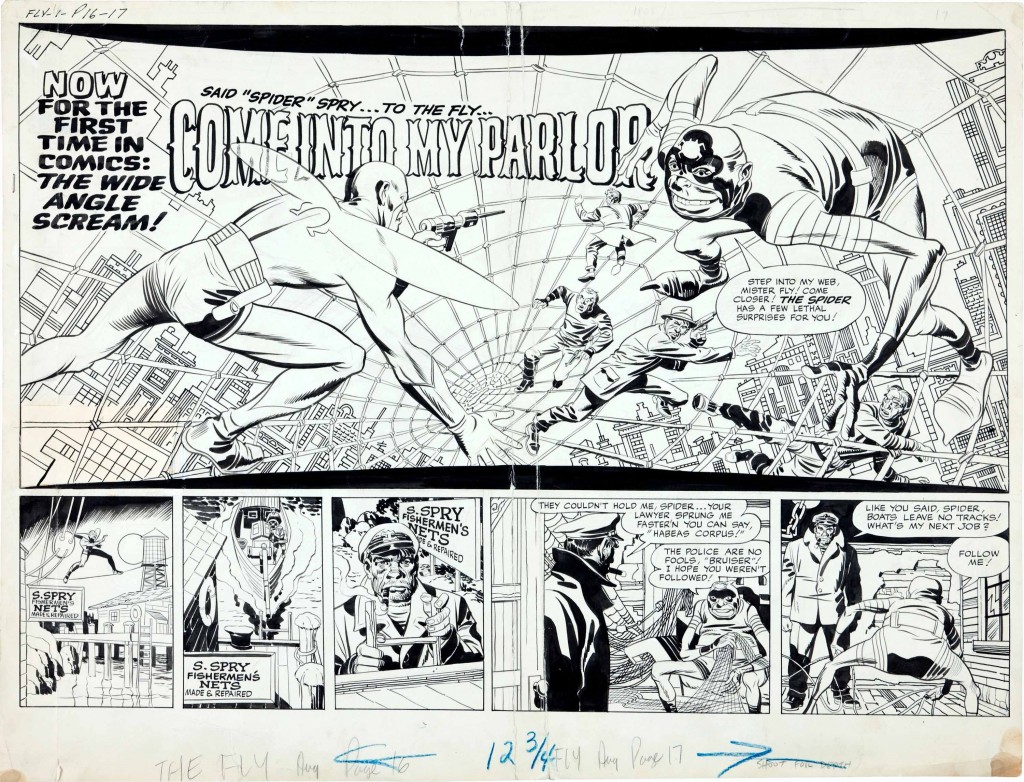

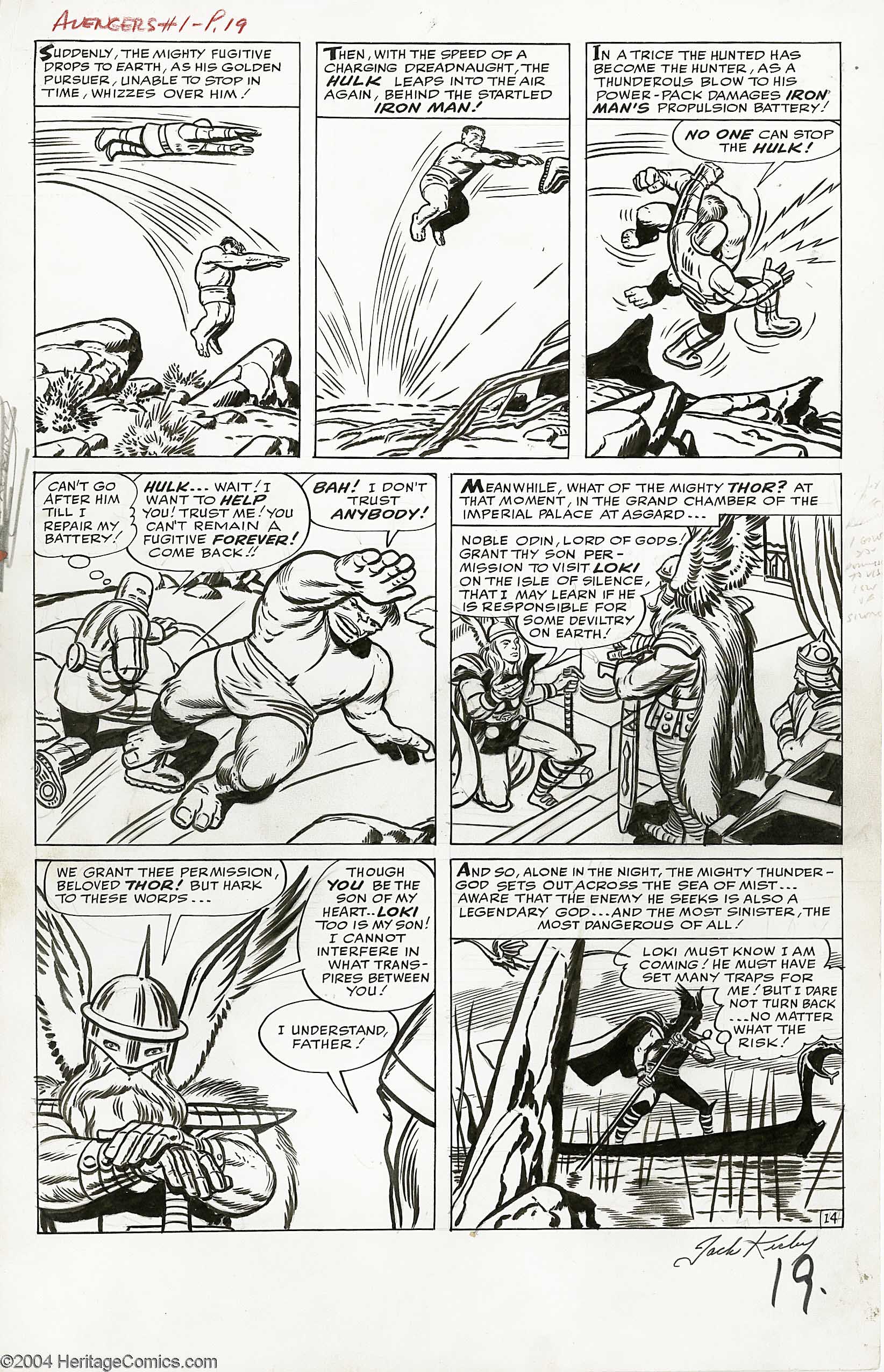

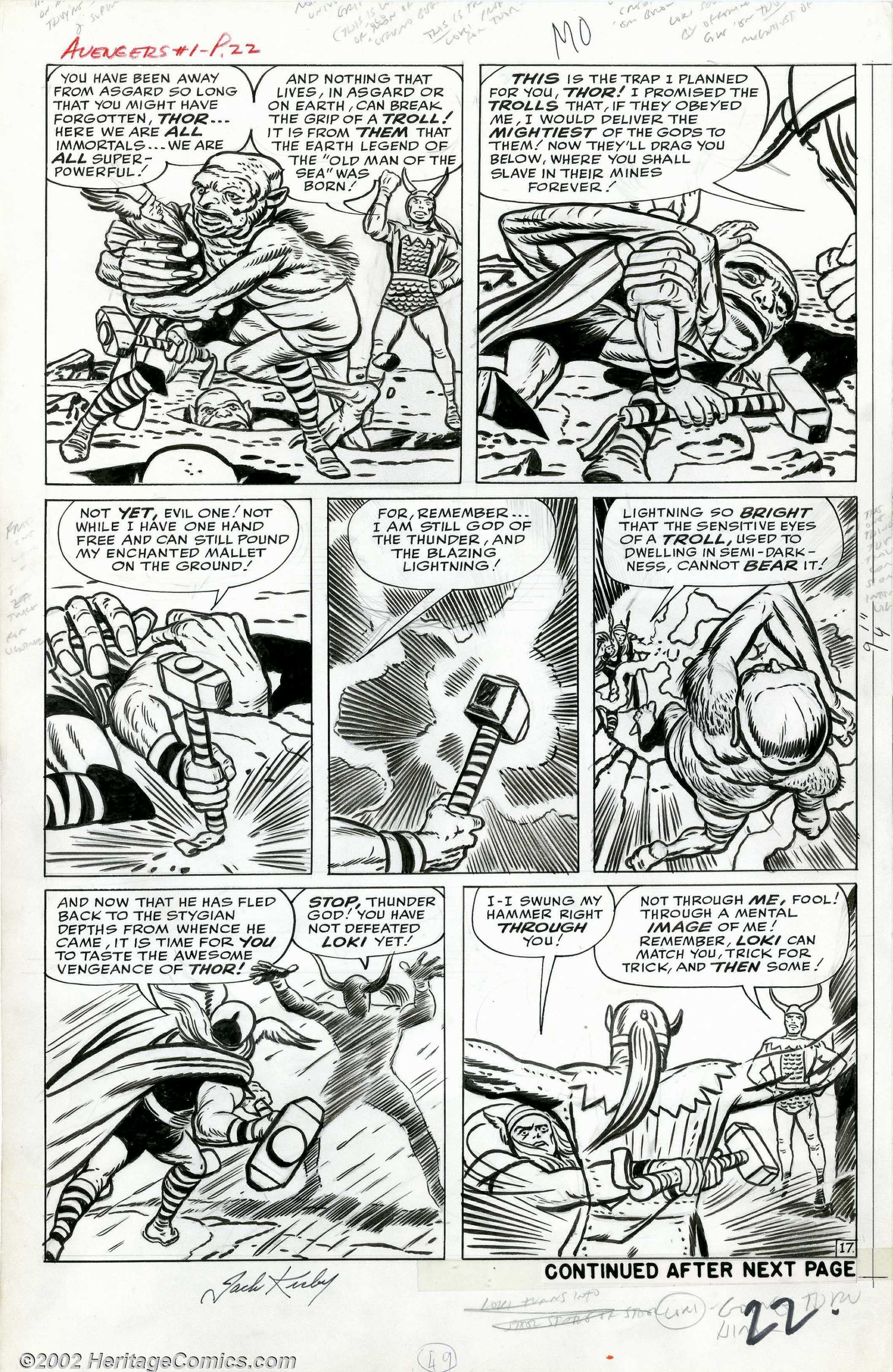

Later on page 14, above we see Iron Man briefly face off against the Hulk and the former is defeated. Notice the cinematic nature of the sequence, where the Hulk’s downward motion trail in panel one moves upward in the second panel. The Hulk then leaps away, snarling his distrust. The scene shifts to Asgard, where Thor seeks out Loki with the aid of his father Odin. The following page below is a wonderment of fantasy action that any filmmaker would be fortunate to match, as Thor wrestles with a demonic Troll, casting him into the depths of a pit.

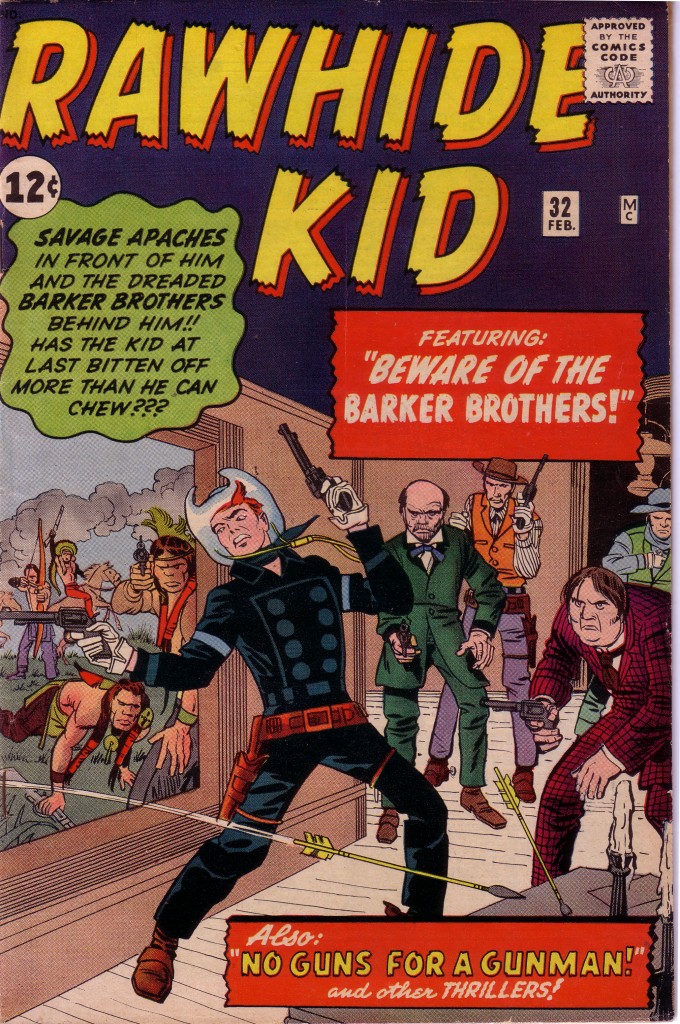

The original Hulk as presented in his own 1962 comic as well as in the Avengers’ first issue was a fairly intelligent and shrewd character, but also one seething with rage and resentment. He was so belligerent that he was utterly incapable of being part of a team, and he was out of the Avengers by the third issue. As time went by, he became more and more incoherent, eventually becoming similar to the character that we see in the film, essentially a brainless hunk of muscle.

It seems that whenever Kirby was plotting the Hulk, as he did in the 1962 comic and in the first three issues of the Avengers, he made the character intelligent, along the lines of the original Mr. Hyde or Frankenstein’s monster as written by Mary Shelly. As soon as Kirby was no longer plotting the character, the Hulk reverted to a half-witted creature. Kirby also plotted the Hulk series in Tales to Astonish beginning with issue #68 and shortly thereafter, the character regained his lost intelligence for a time. In the two Hulk films as well as the Avengers movie, the Hulk is a computer generated image or CGI creation, and is presented as a fairly mindless engine of destruction. I don’t much care for the look or the persona of the movie Hulk. Kirby’s original wily and sinister Hulk is for me a much more compelling and fascinating creature and I would have much preferred to see that character onscreen.

Allow me to digress here. One can draw an interesting parallel between the way the Hulk was treated throughout his comic book and film history and the way that Jack Kirby was perceived and treated by Stan Lee and Marvel over time. Kirby seemed to identify with the Thing and the Hulk, characters who, like him were rough edged and uncouth, possessing robust physical strength and animal vitality. It was easy for some to overlook Kirby’s intellectual and introspective side, as did a Herald Tribune journalist doing a 1966 piece on Marvel when he described Kirby as looking “like the assistant foreman in a girdle factory.” It may be a bit far fetched, but my feeling is that Kirby’s urge to make the Hulk intelligent reflected his own desire to be perceived as someone with a mind to be reckoned with. It is easy to see the Hulk emasculated of intelligence in a similar way that being categorized as merely an artist somewhat emasculated Kirby.

Many people saw Kirby as a sort of idiot savant, who needed Stan Lee to make his ideas coherent. Artists are often seen as being blessed with god given talent, but few people are aware of the amount of work that is required to hone that talent and the intelligence that is necessary to apply it. In the early days of the Comic book field, the businessmen that controlled the purse strings did not generally give artists much respect. Just as physical power is often perceived as being less threatening without a brain to support it, Kirby as merely a tool to interpret Stan Lee’s ideas became less threatening even in an art form dominated by its visuals.

In a 1968 interview in the magazine Castle of Frankenstein, Lee originally stated: “Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s make the next villain be Dr. Doom’… or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He’s good at plots. I’m sure he’s a thousand times better than I. He just about makes up the plots for these stories. All I do is a little editing… I may tell him he’s gone too far in one direction or another. Of course, occasionally I’ll give him a plot, but we’re practically both the writers on the things. ”

When in 2009, Kirby’s family attempted to claim the copyrights to characters that Kirby had more than a hand in creating, Marvel/Disney sued them in New York federal court, claiming that the characters had been created as work for hire. Suddenly, Stan Lee was less effusive in his praise for Kirby’s creative abilities. In his May 13, 2010 deposition, Lee explained away the glowing praise and credit that he had given Kirby thusly:

“I tried to write these (The Origins books) —knowing Jack would read them—I tried to make it look as if he and I were doing everything together, to make him (Kirby) feel good. But with something like Galactus it was me who said, “I want to do a demi-god. I want to call him Galactus.”

Jack said it was a wonderful idea, and he drew a wonderful one, and he did a great job on it. But in writing the book (Origins of Marvel Comics) I wanted to make it look as if we did it together. So I said we were both thinking about it, and we came up with Galactus.”

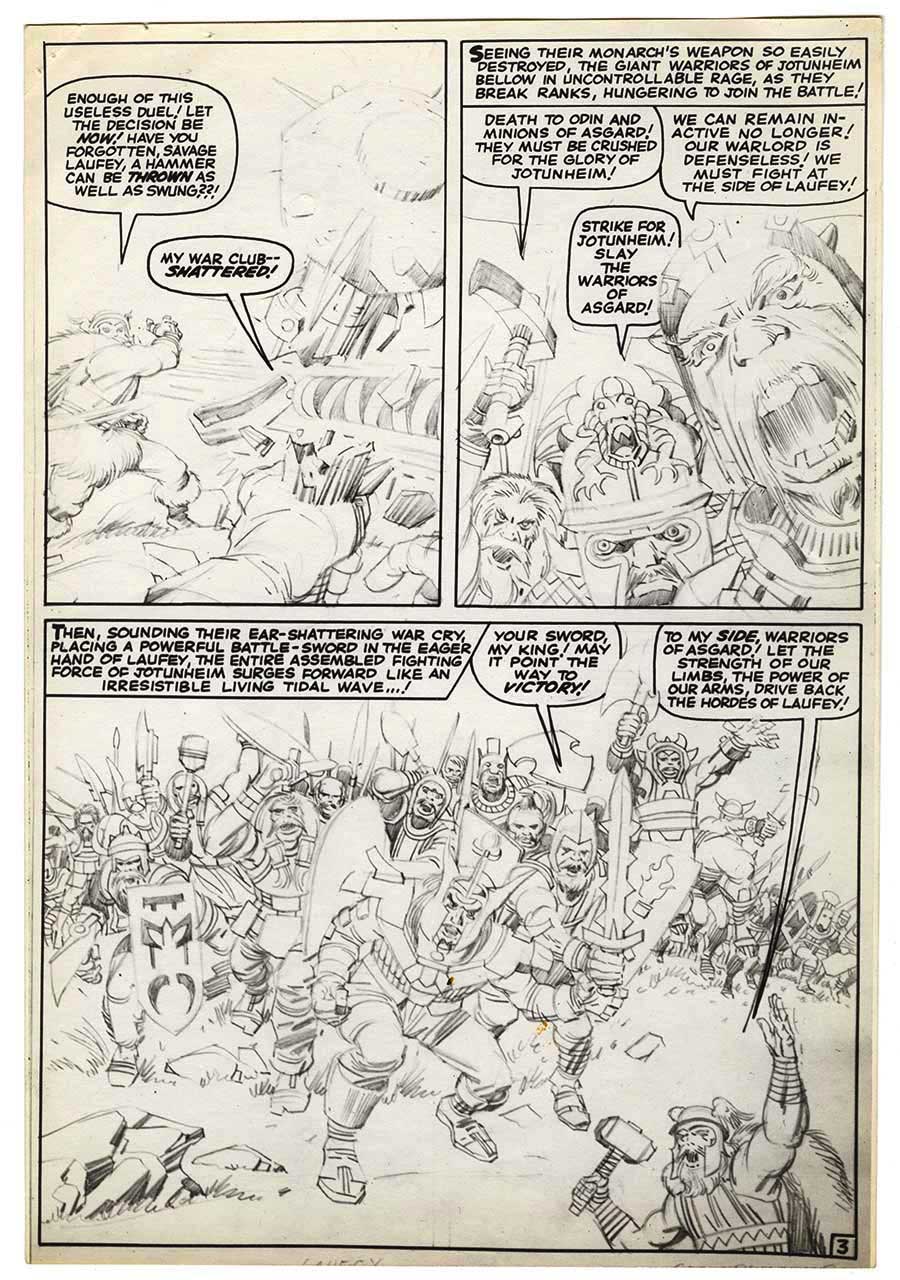

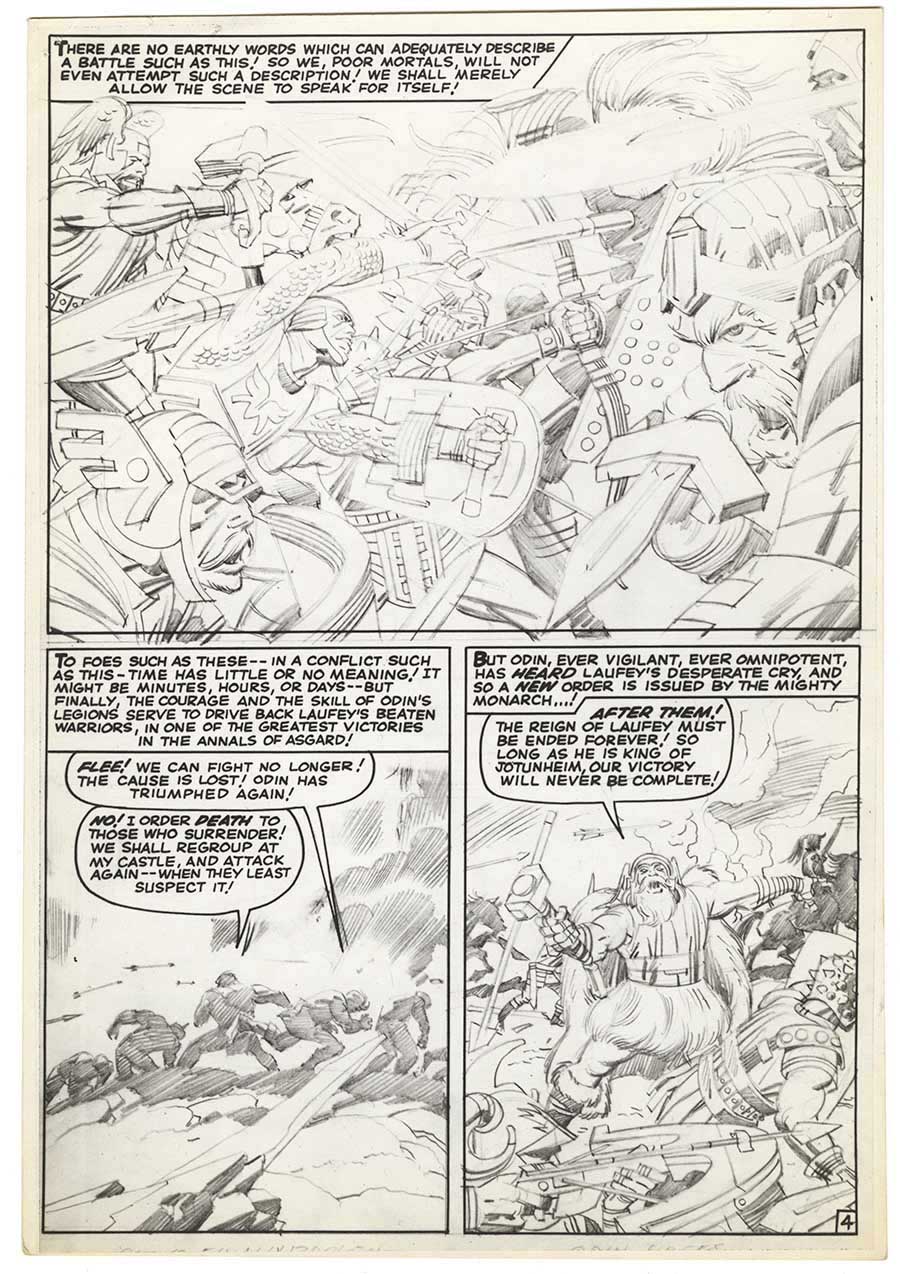

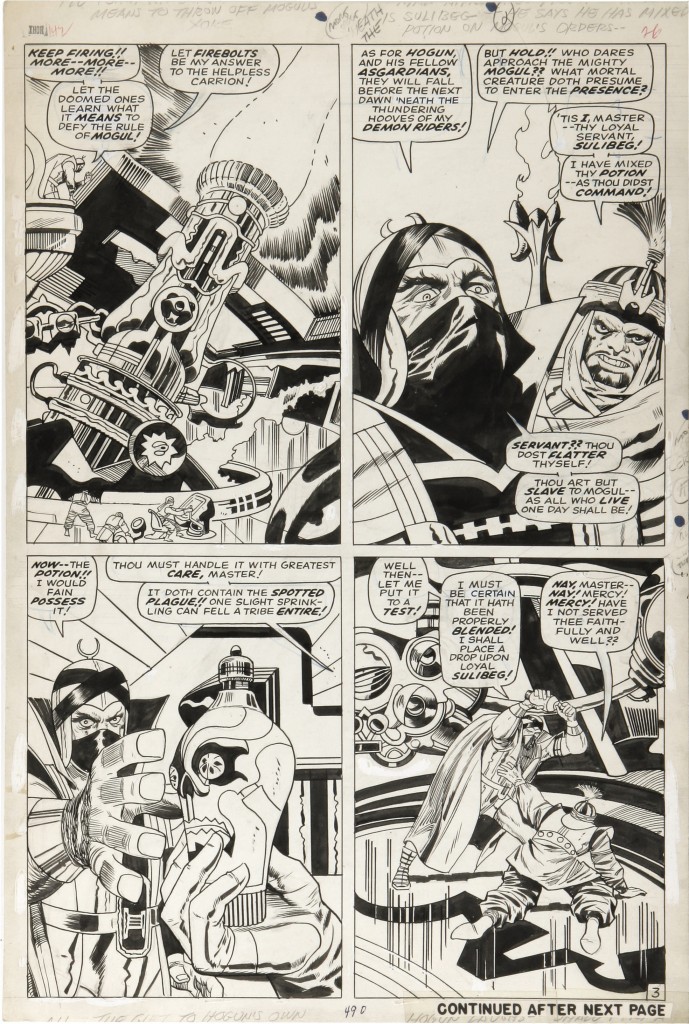

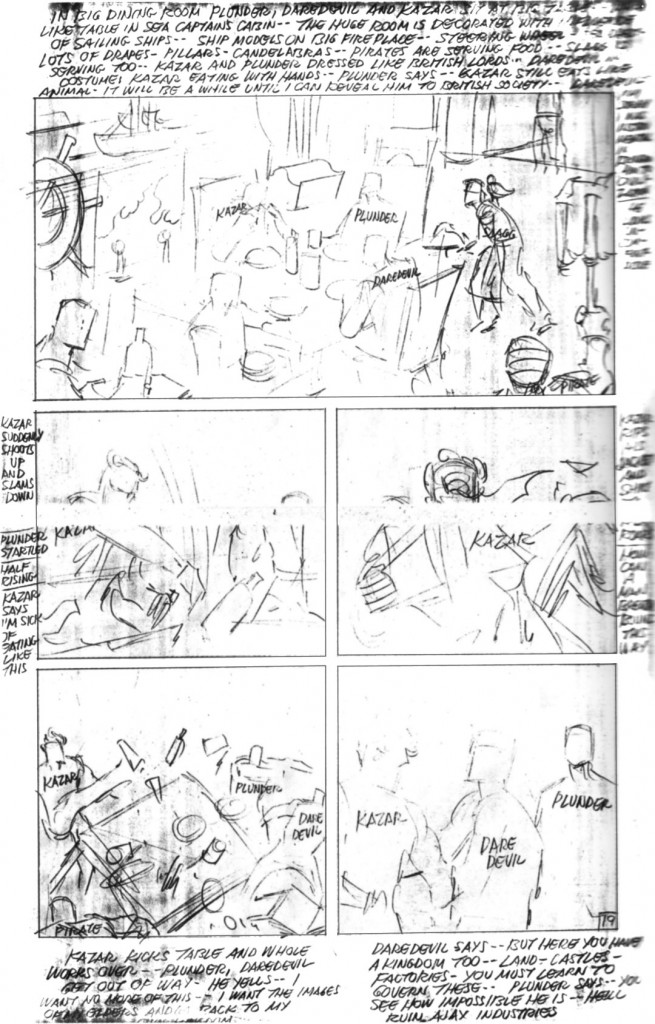

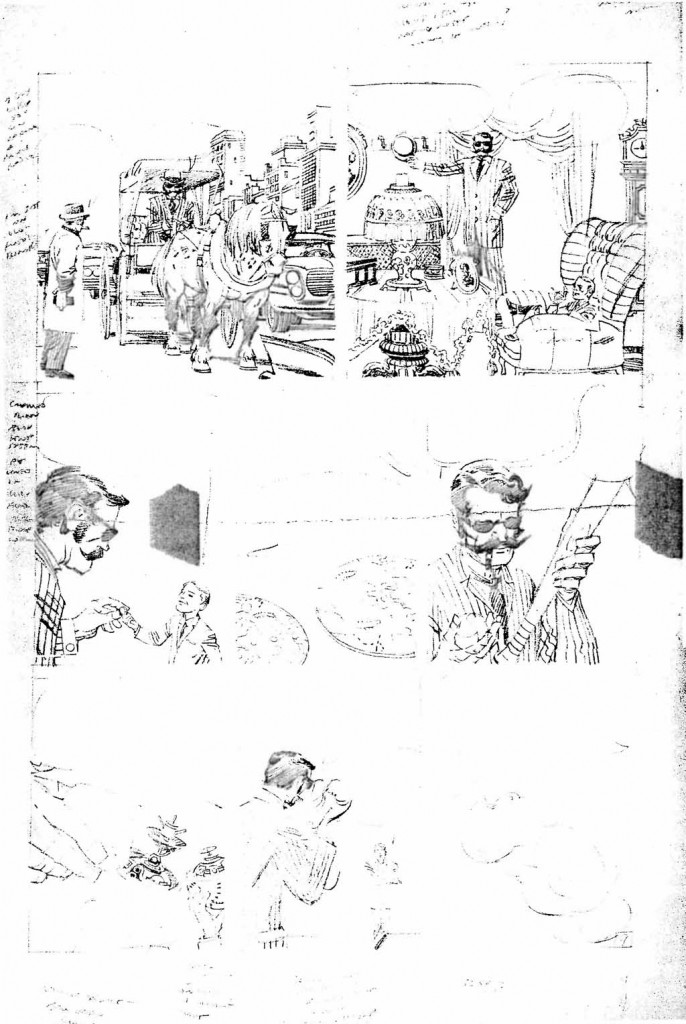

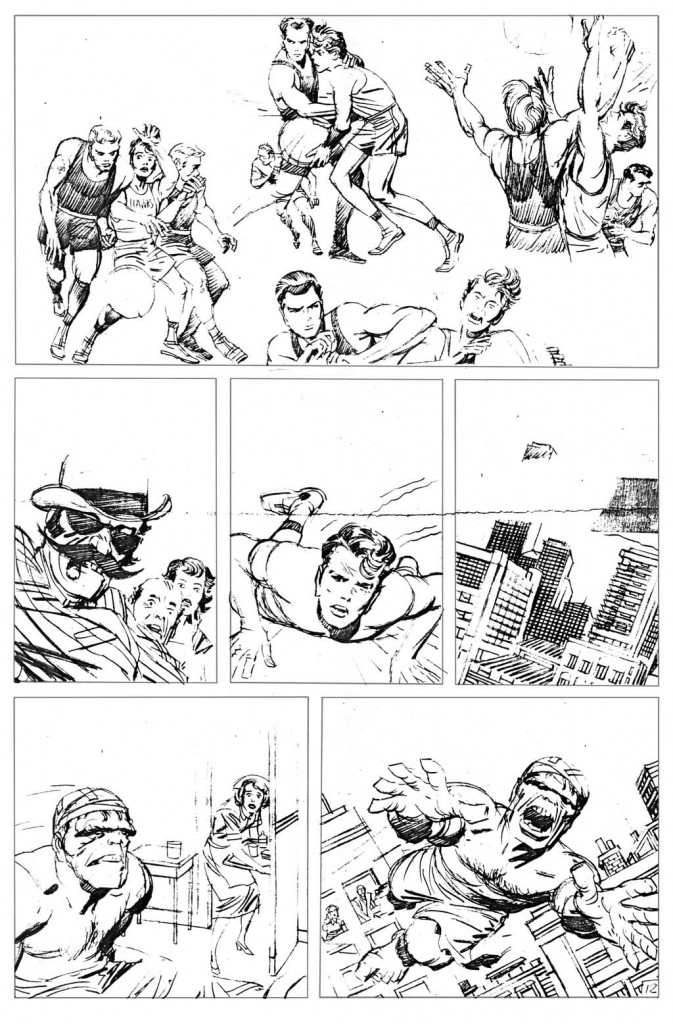

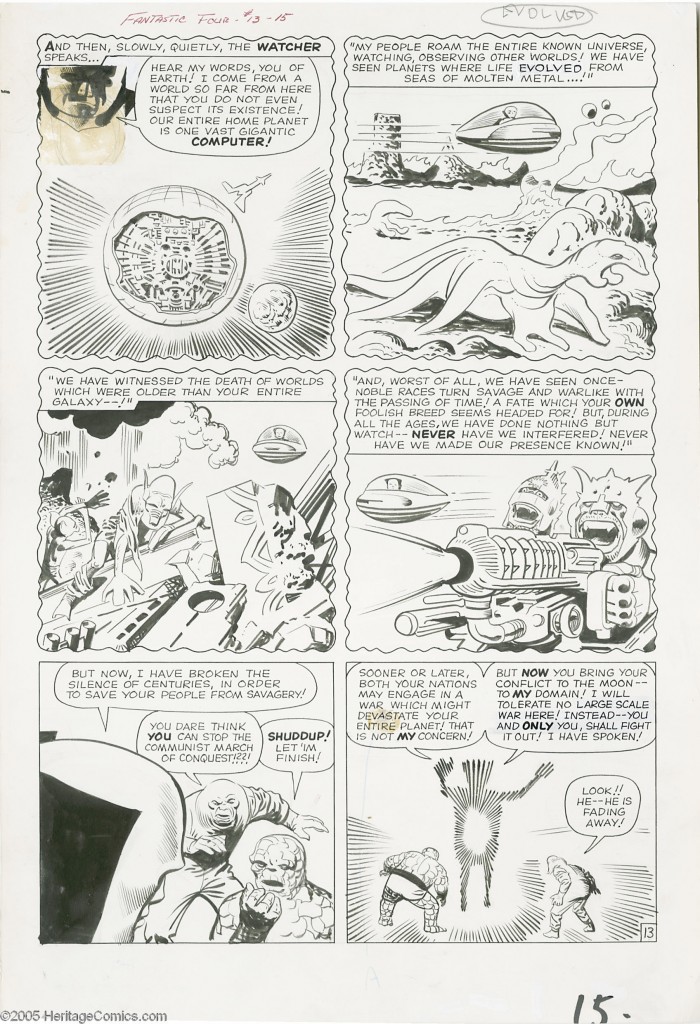

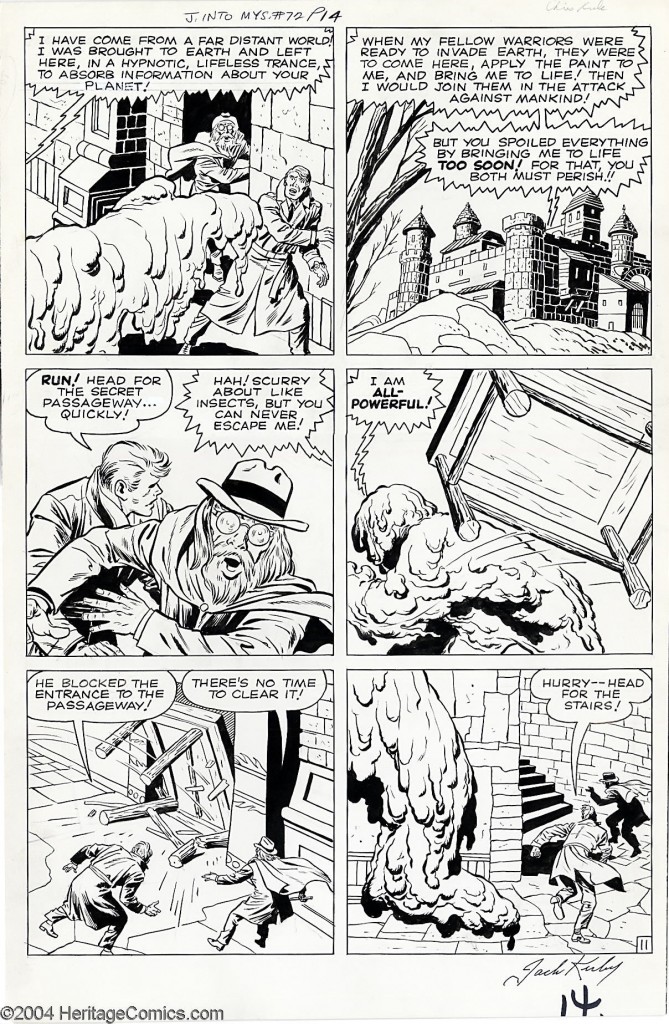

Now, we can clearly see Stan Lee’s margin notes on these Avengers pages. Judging by the account in my last blog entry of Kirby’s delivering some 1962 Hulk pages to Lee, and seeing that some were marked with notes prior to Kirby’s storming out and tearing the pages in half, we can surmise that a similar process has occurred with the Avengers pages as well. That is, Kirby had brought Lee a complete Avengers story to dialog and Lee made notes during his meeting with Kirby for the former’s scripting efficiency. These pages date to more than a year before most comic scholars surmise that the Marvel method went into effect, that being the plotter/artist leaving his own notes in the margin for the scripter to follow. Clearly, at some point it was decided that instead of Kirby coming into the Marvel offices with his plotted artwork for a story conference, it was more efficient to mail the pages with his own notes.

If the evidence shows that Kirby was plotting stories prior to meeting with Lee, what reason would we have to believe Lee’s testimony that Kirby was not a major part of the creative process. Obviously, we are dealing with a highly volatile issue here, concerning several parties telling very different stories about a process. We can only look at the evidence, and in this case it appears to tell us that Jack Kirby was plotting and delivering ideas and characters, either from the beginning of his tenure at Marvel or certainly very shortly thereafter. Not only does Kirby’s body of work as a comic book professional verify this, the various people that worked with him over the decades confirm the fact that Jack Kirby had been a primary creative force for as long as he worked in comics.

The simple fact is that Disney/Marvel has made and stands to make untold billions from these properties, and they need to recognize and properly compensate Jack Kirby’s estate for his amazing contributions to their empire.

Image 1-Marvel’s The Avengers

All other images from The Avengers #1 Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Dick Ayers

All scans of original art courtesy of Heritage Comics

Brent Staples quote from New York Times May, 14 2008 The Man Behind Iron Man.

Stan Lee quotes from Castle of Frankenstein 1966 and New York Federal, Court May 13, 2010

Thanks to Patrick Ford and Steven Brower for their assistance.