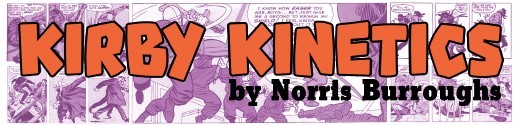

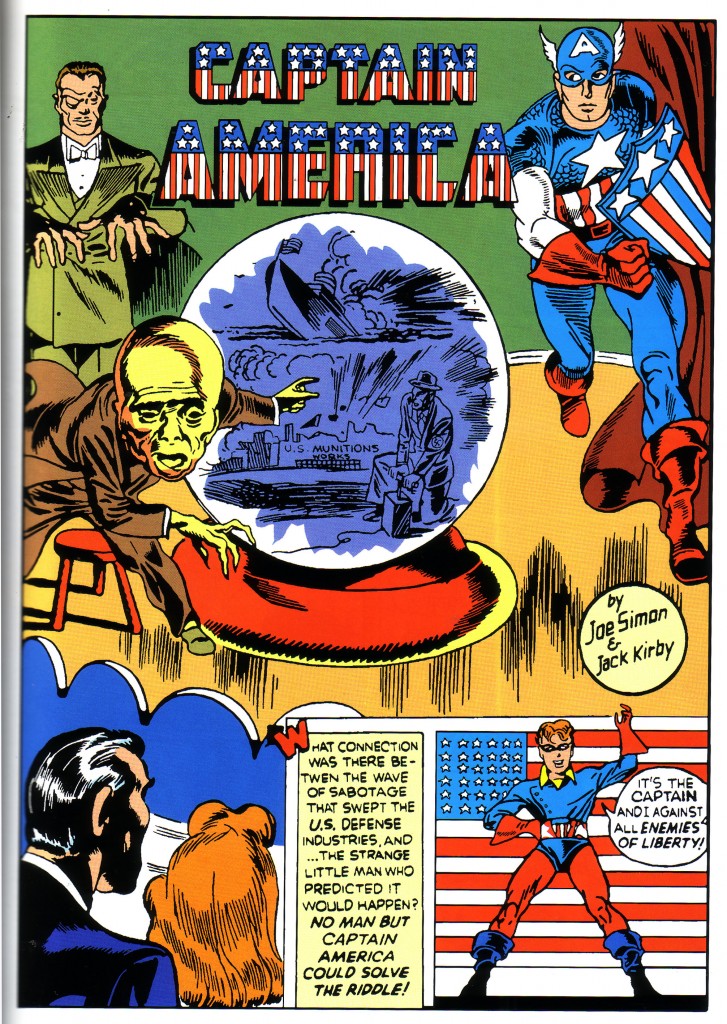

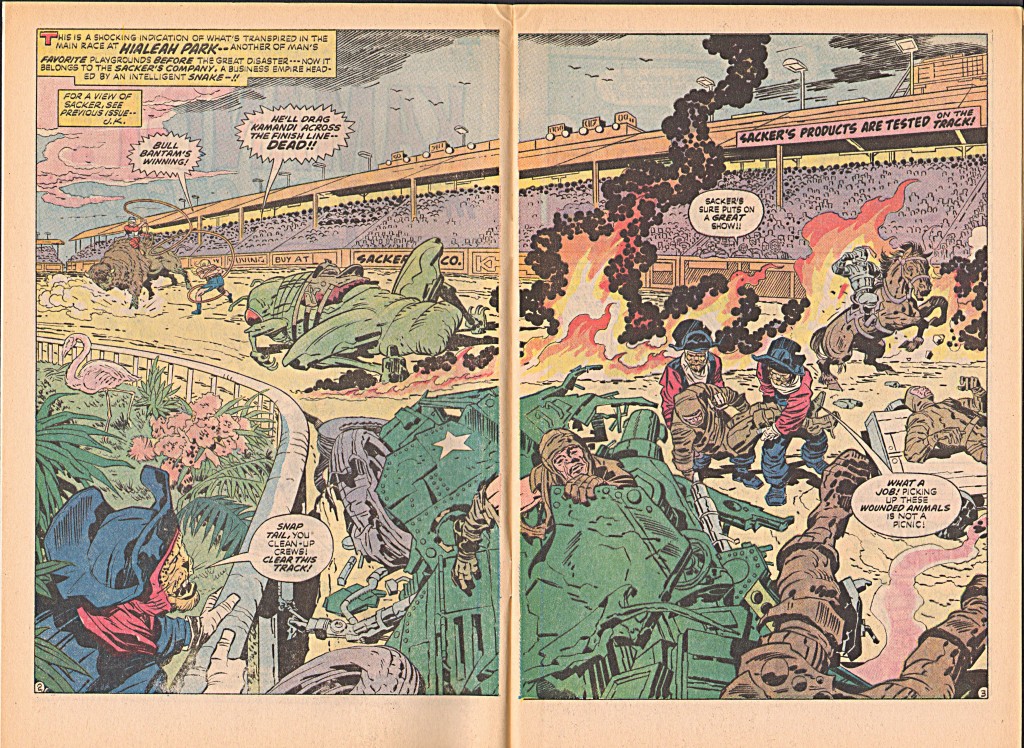

Like many of his peers in the early years of the Comic Book industry, Jack Kirby was fascinated by technology. He was also a fan of the emerging arena of science fiction and fantasy film and literature that were akin to it. Here is a page from a publication called Real Fact Comics, produced by Kirby and Joe Simon circa 1946. This is clearly an attempt to merge science fact and fiction in imaginative speculation on future intergalactic technology.

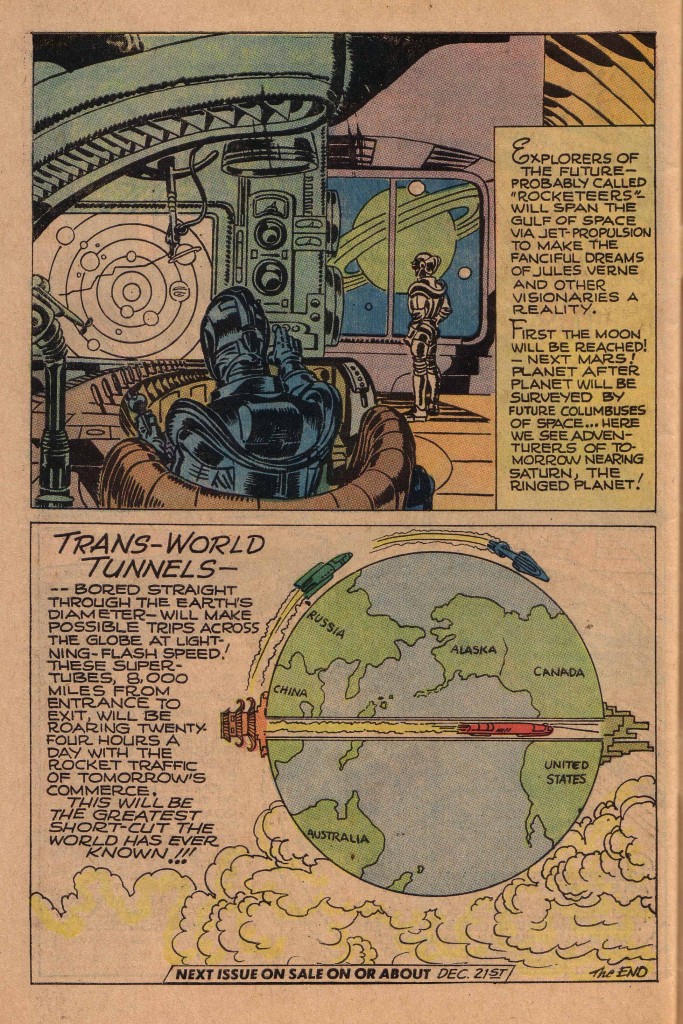

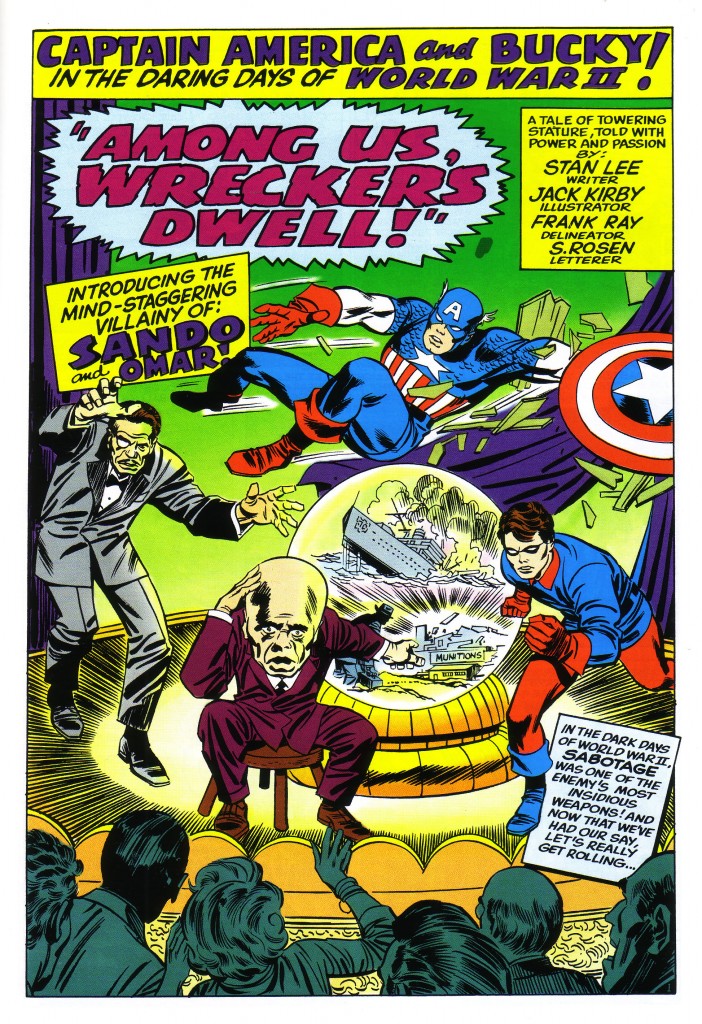

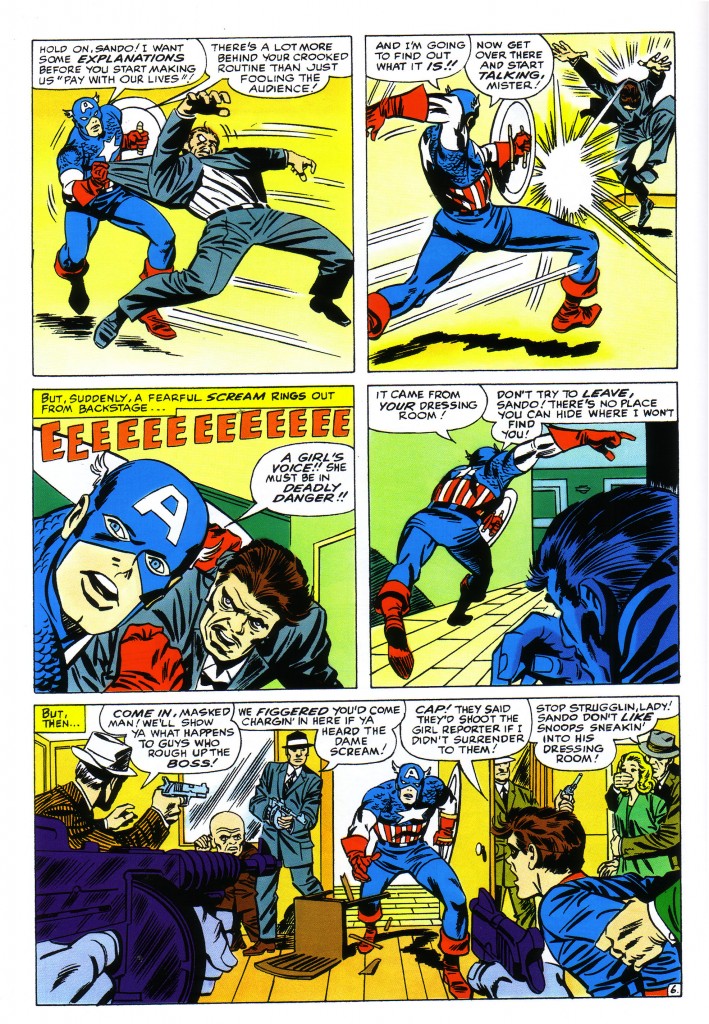

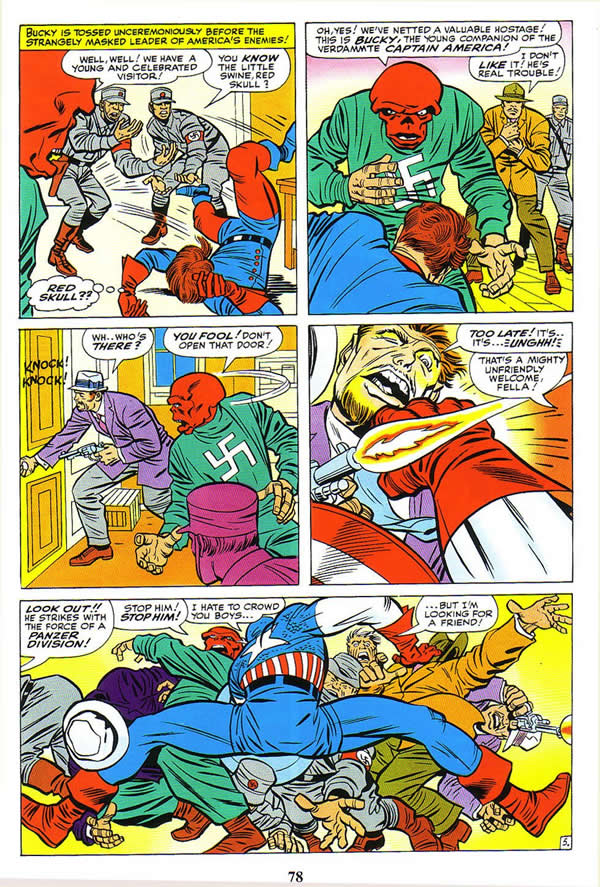

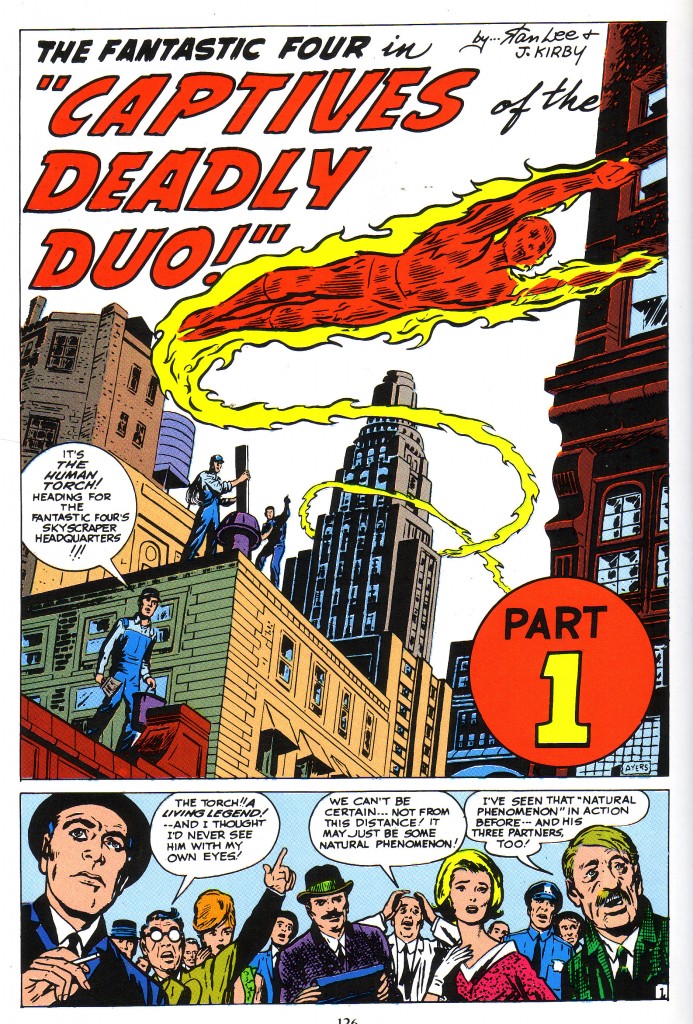

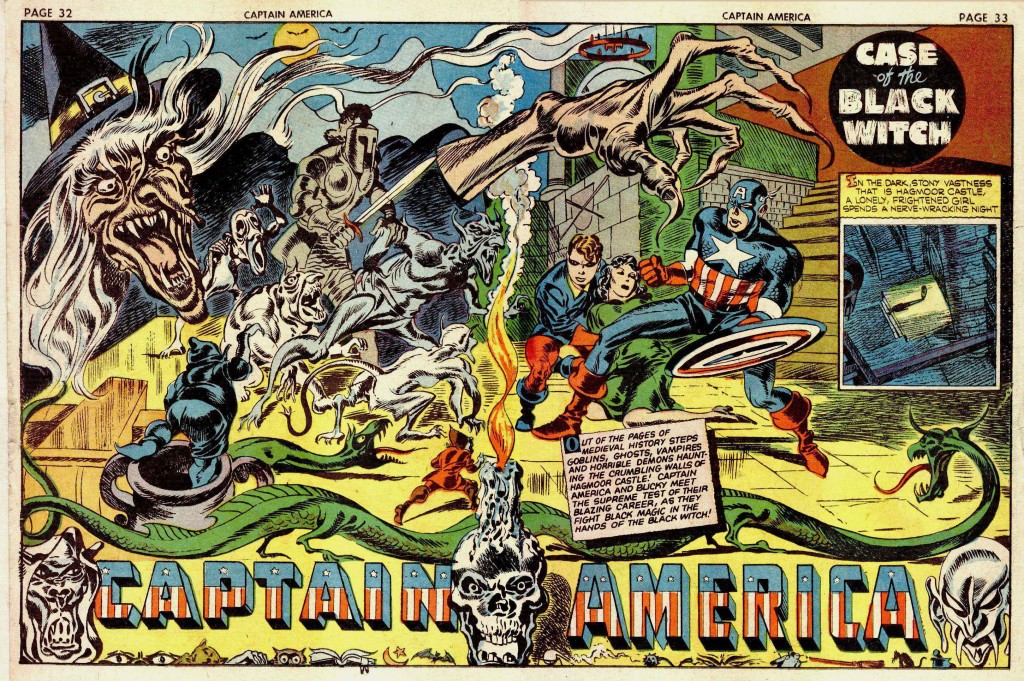

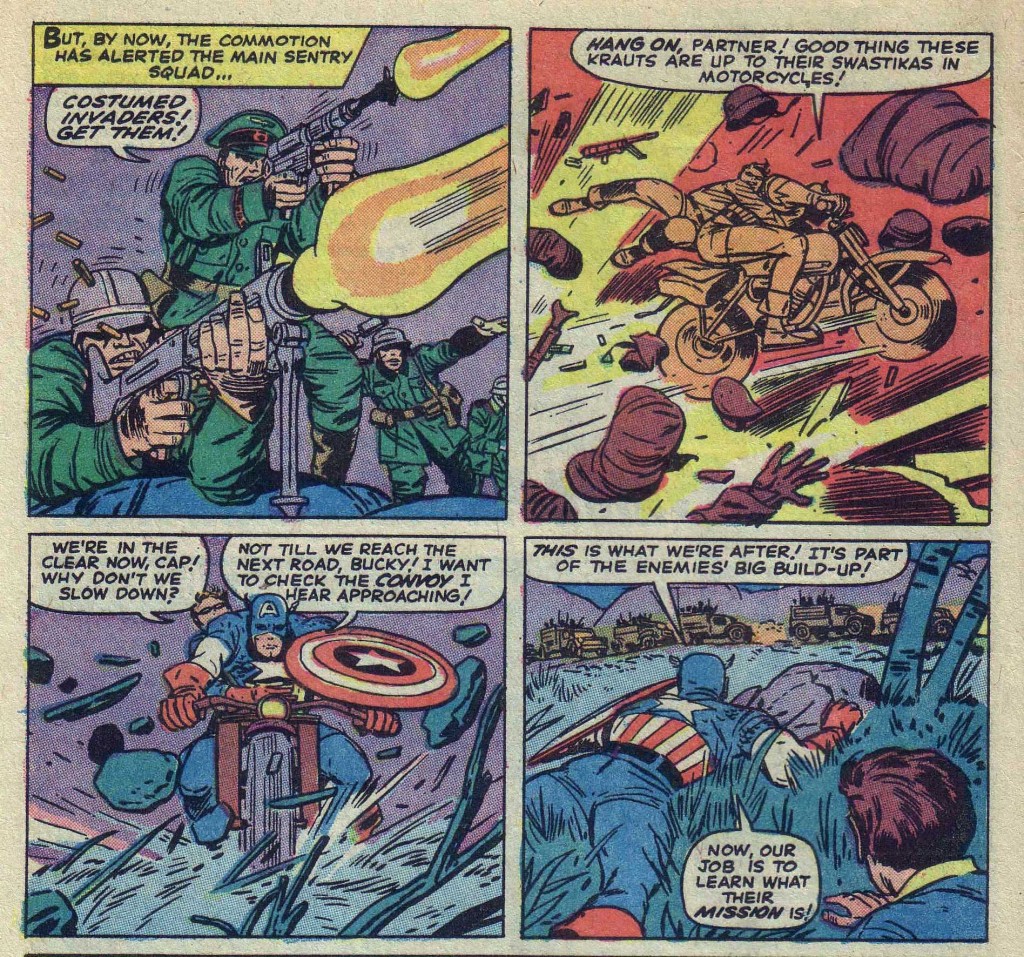

If we look at the style of drawing in which Kirby was working during this period, we see that he is hewing fairly close to a naturalistic, albeit dynamic style. A page from an earlier Newsboy Legion strip shows the artist drawing musculature pretty organically, rendering bone and sinew in an somewhat accurate though stylized manner. Details such as pectoral and deltoid muscles are in the correct position and although they are used in the compositionally optimal Kirby fashion, they look more or less as they ought to.

What we may notice in panels one through three is that Kirby is using the structural details of the rooms to emphasize the dynamism of the compositions, something that he would do more and more effectively as his career progressed. For example, in panel one, Kirby uses the circular sweep of the floor and walls to emphasize the forward and diagonal propulsion of the action figures.

For more detailed examples of this, see my posts on Architecture.

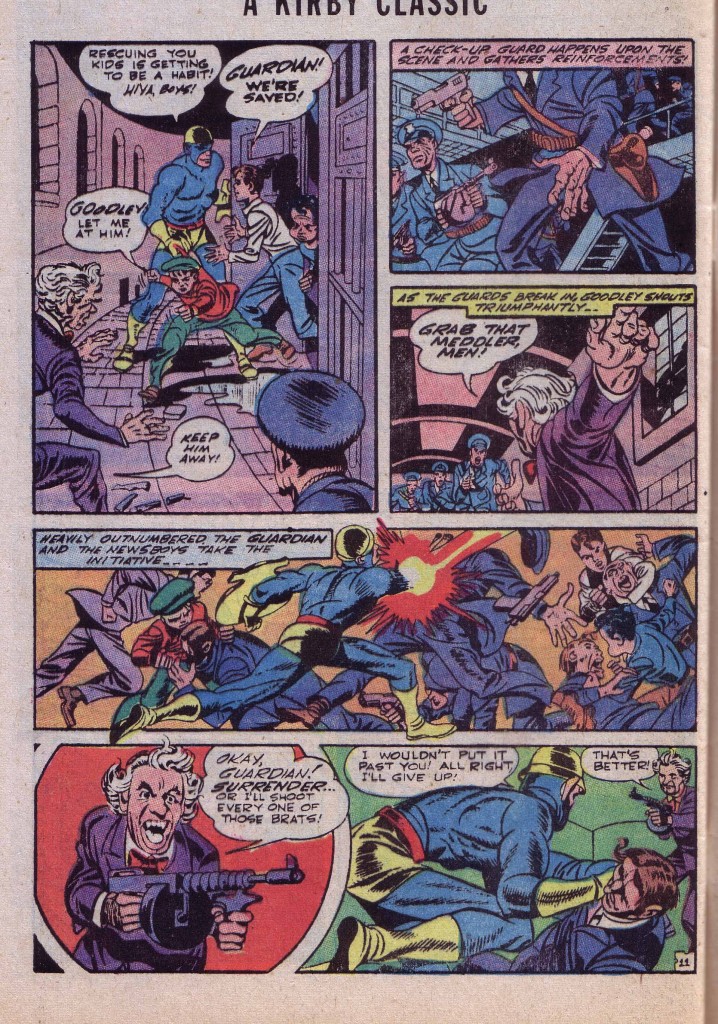

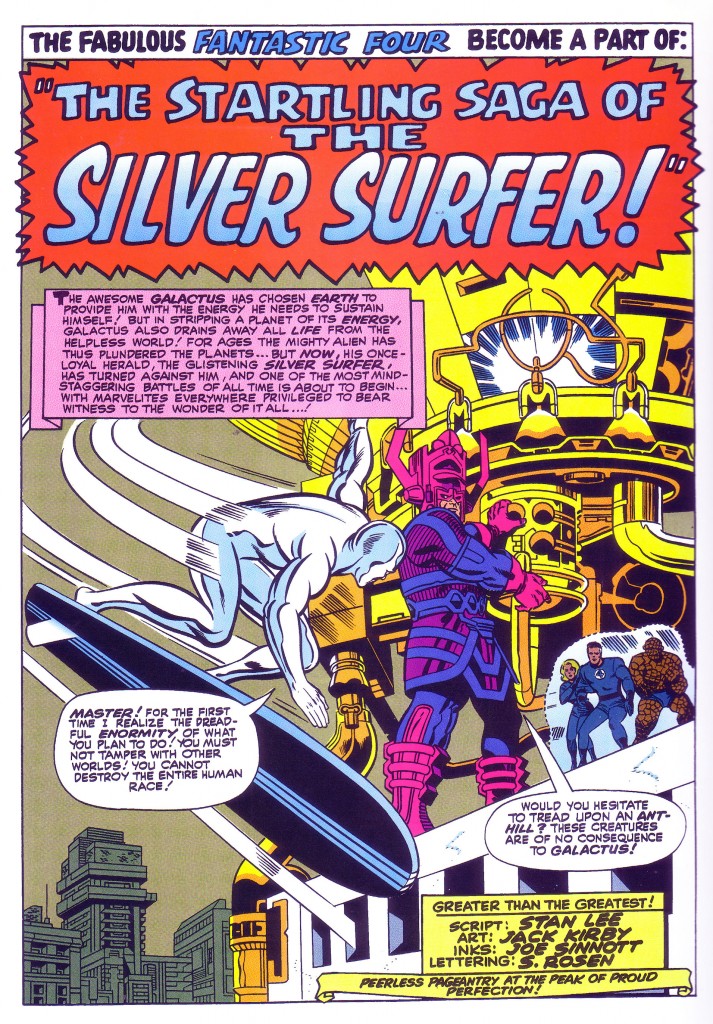

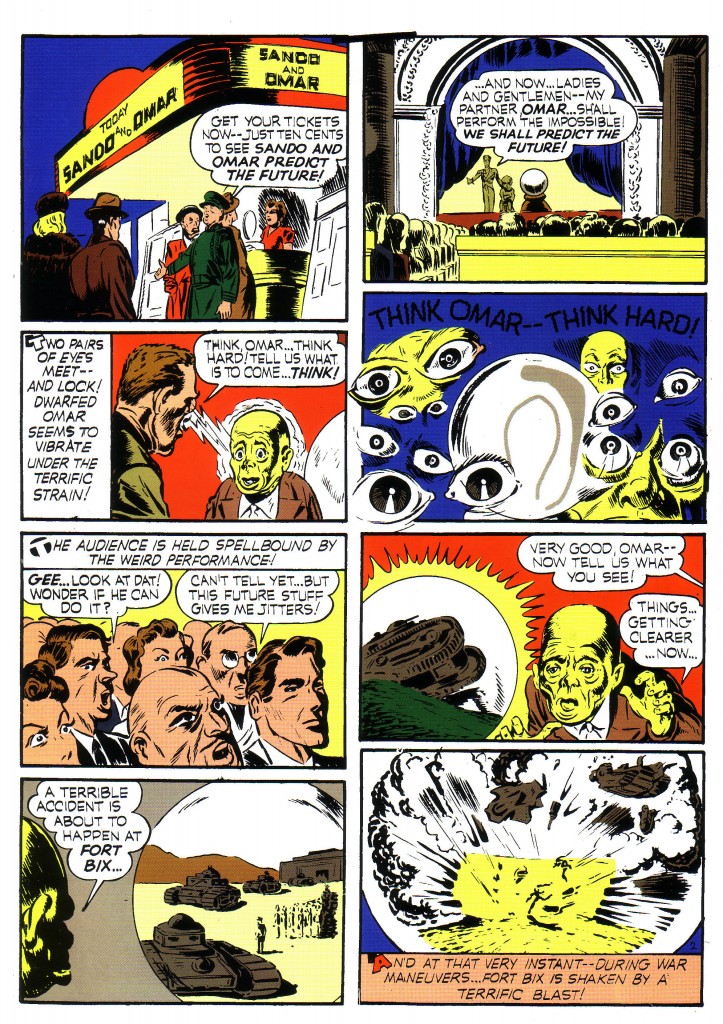

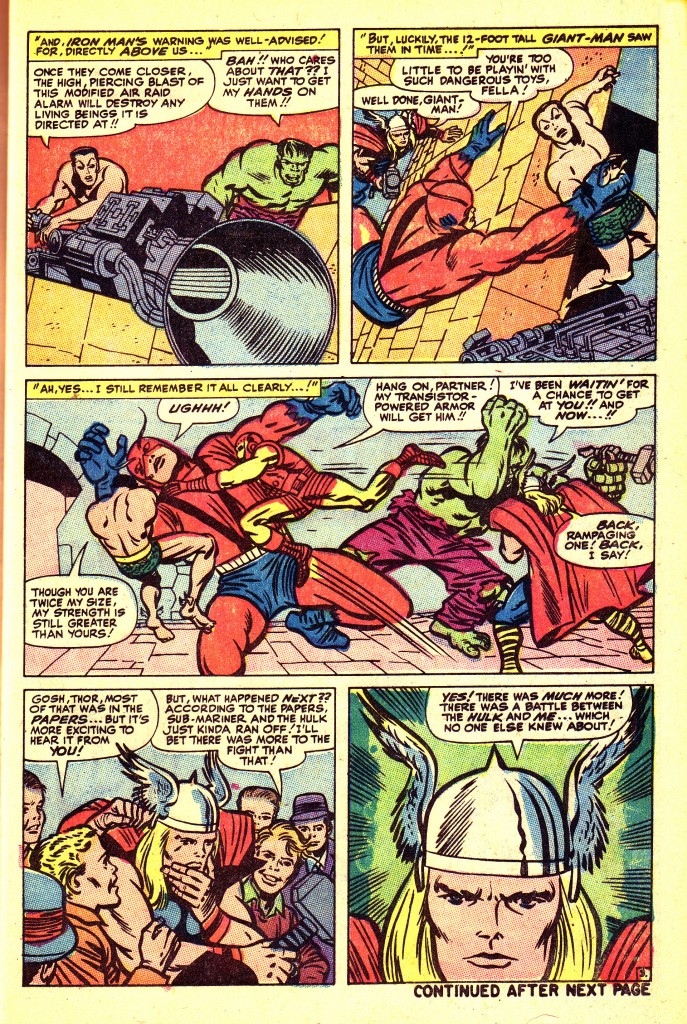

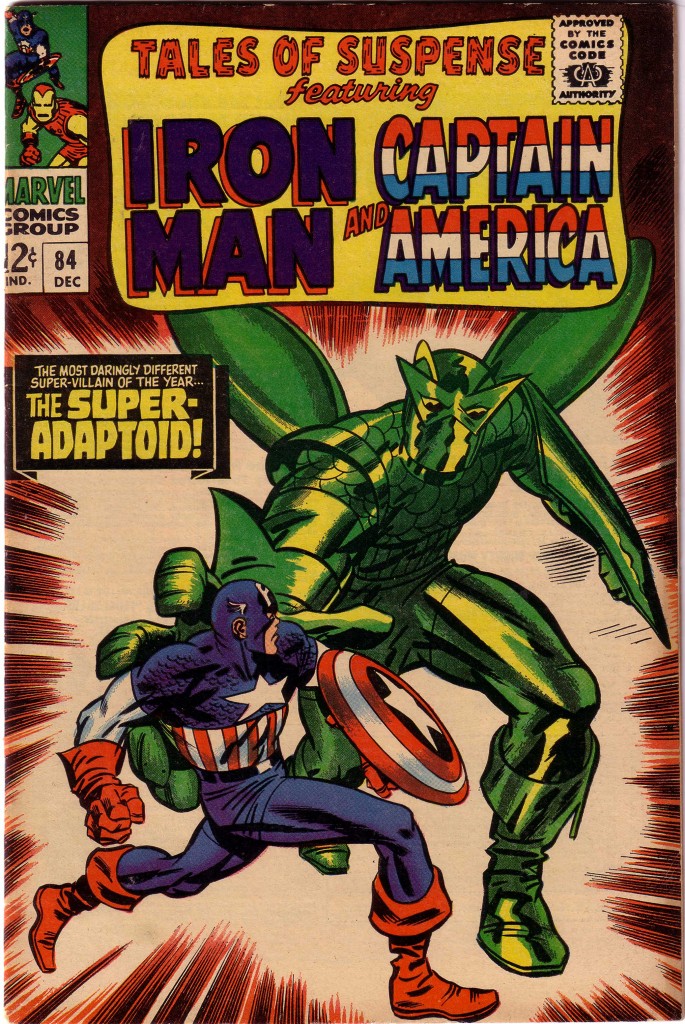

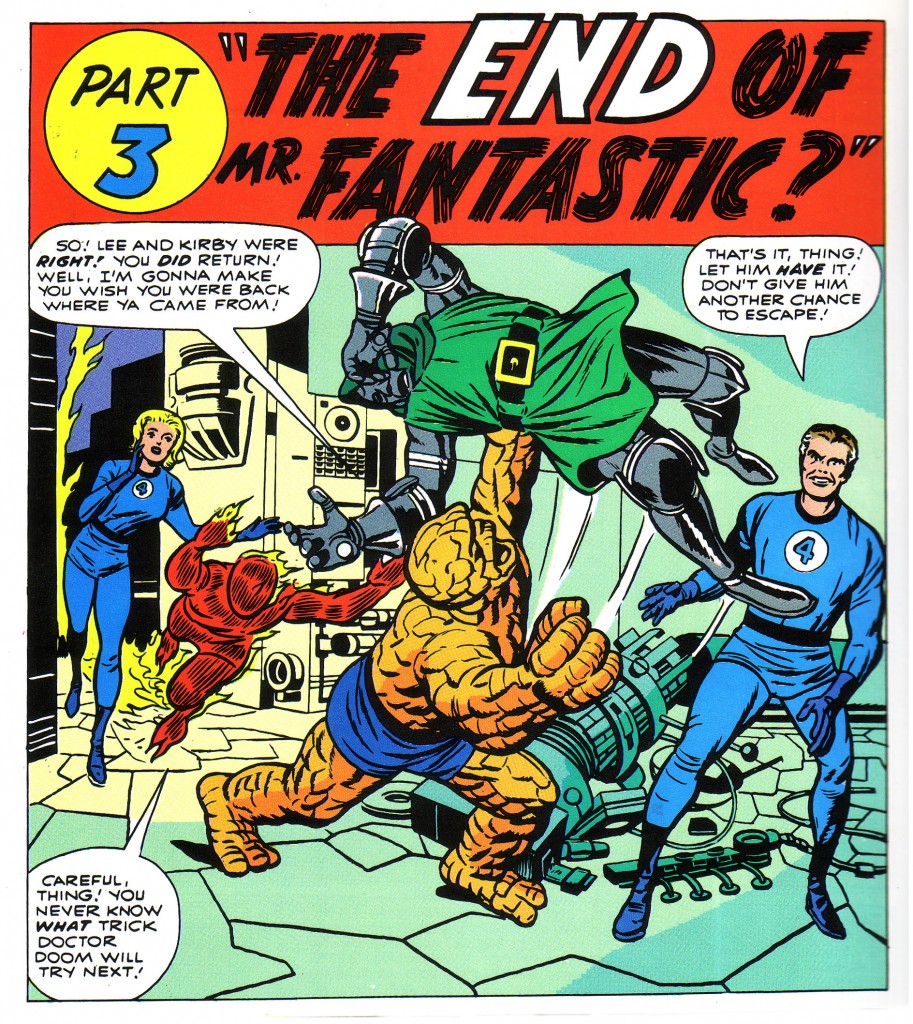

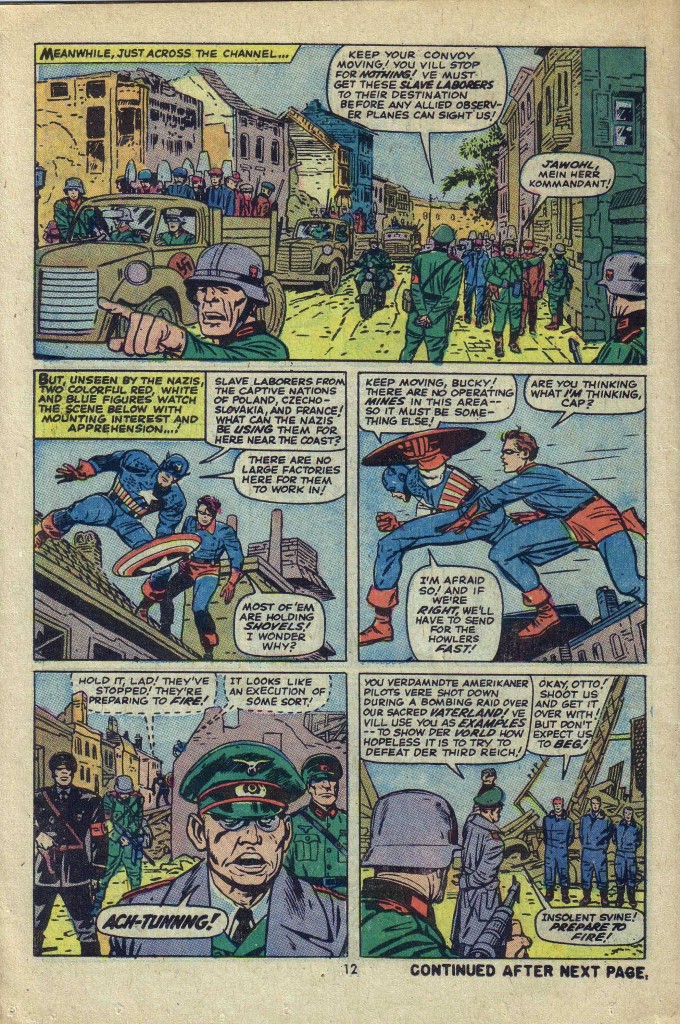

As his career moved into the sixties, a singular change occurred in the way Kirby drew the figure. Kirby began to increasingly render musculature with a signature squiggly stroke that became so identifiably Kirby that it became known as “Kirby Squiggles.” This stylistic affectation had the effect of making his figures somewhat less organic and apparently more technologically futuristic. Such a style was perfect for the space traveling Silver Surfer, who was surely a harbinger of things to come when he first appeared early in 1966. The Surfer’s cosmic environment reinforced Kirby’s preoccupation with futuristic technology. This profusion of squiggles often coincided with the generous use of Kirby Krackle during this period, as seen on this cover of Fantastic Four #72.

The King seemed to be possessed with a fascination for glistening chrome-finished machinery that pulsed with energy and appeared to proliferate like inorganic vegetation.

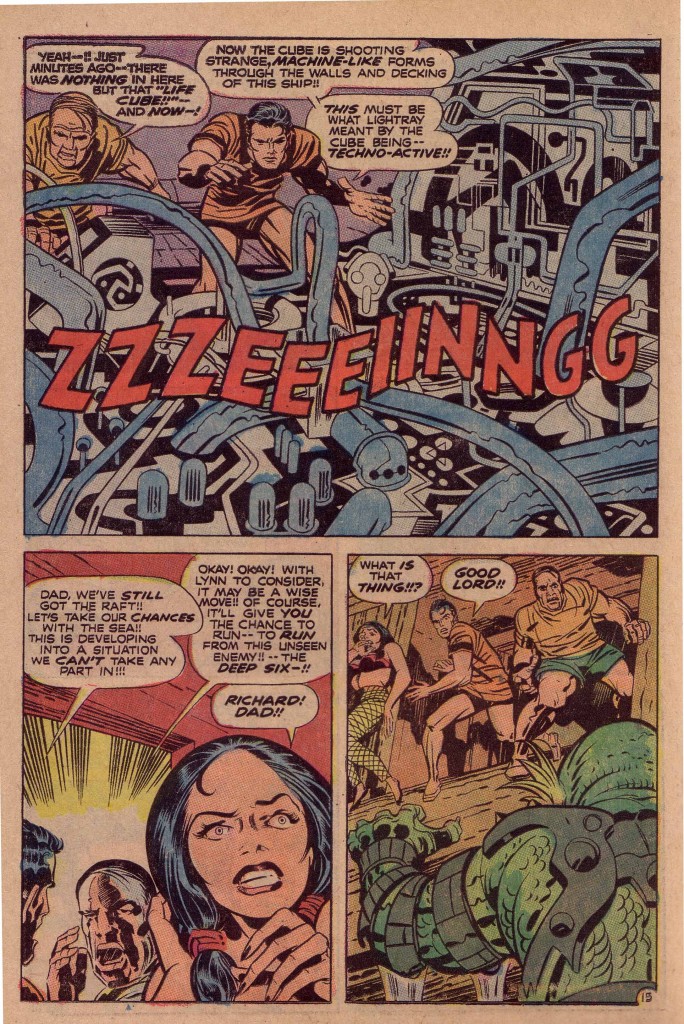

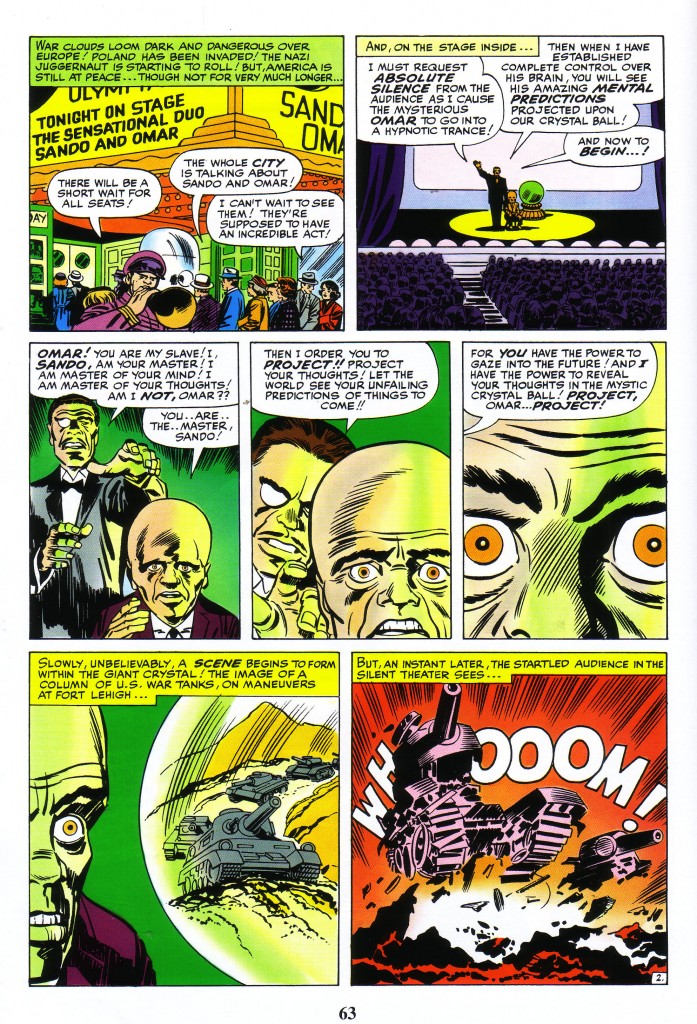

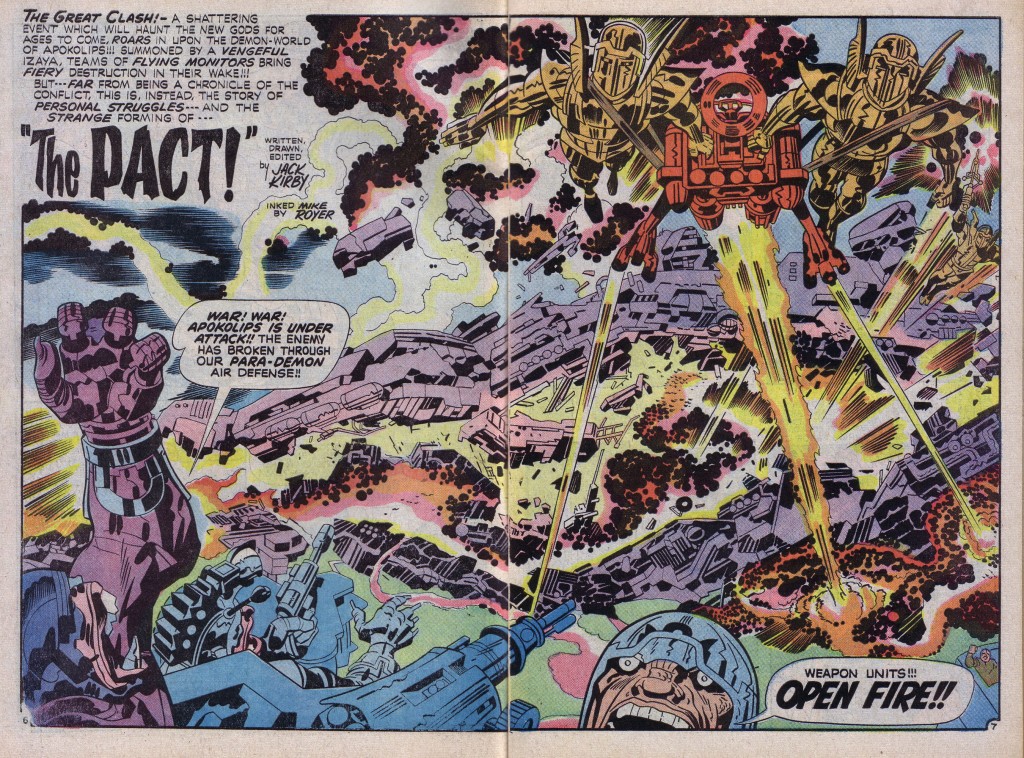

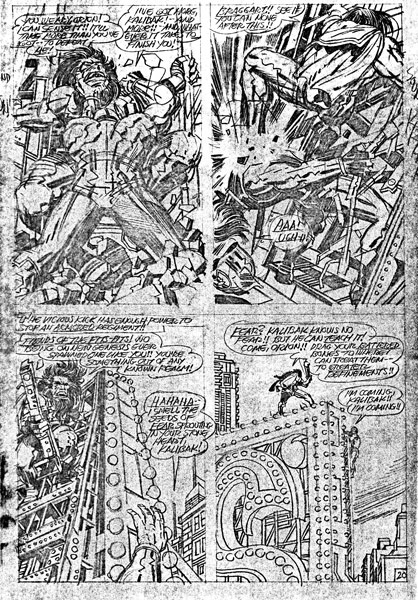

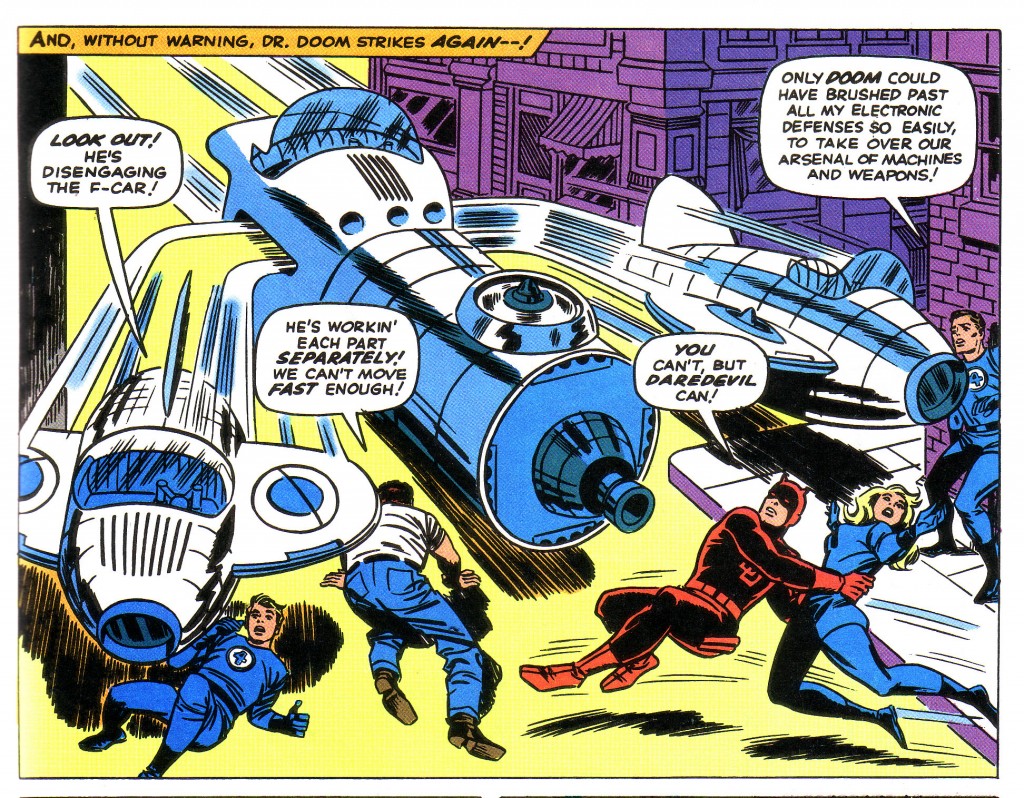

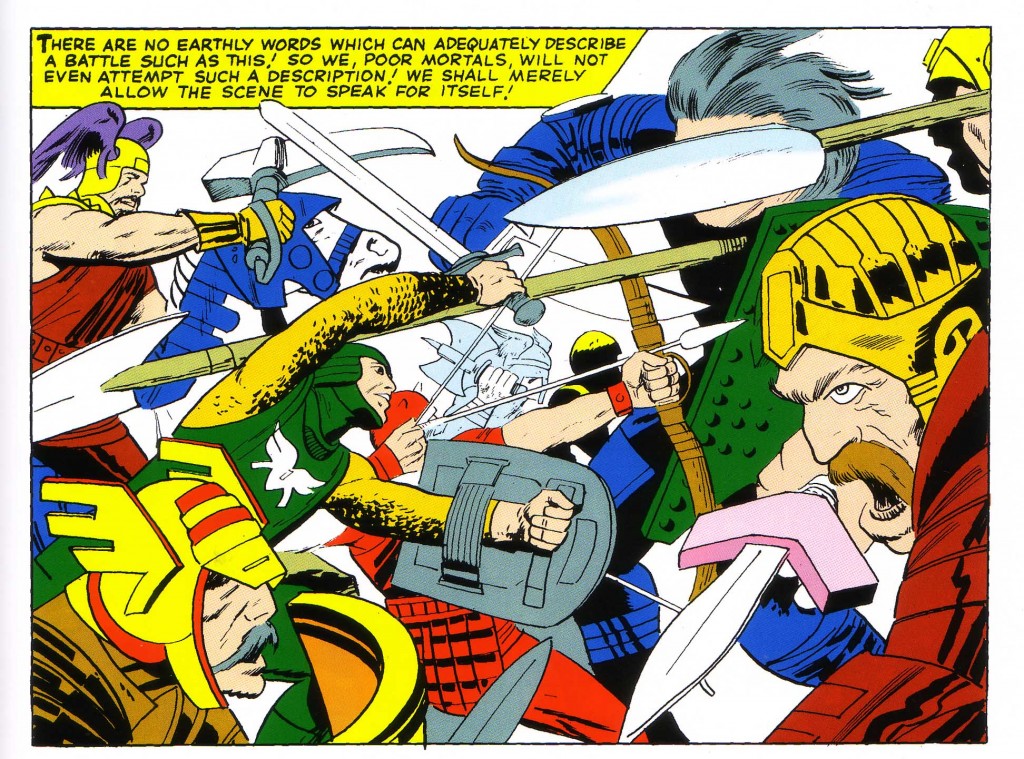

One of the most outstanding stories Kirby produced shortly after leaving Marvel Comics was The Glory Boat, from New Gods #6. At a pivotal point in the narrative, the heroes Orion and Lightray discover a horrific creature in the hold of a misshapen wooden boat. Instead of destroying it, Lightray decides that it should be changed into something else.

The creature is a slithering green monstrosity, with slimy tendrils protruding in multiple directions, symbolic of demonic nature gone mad. Strangely, Kirby in the gradual transition in his art to a less organic depiction of life gives us an encapsulation of his newer paradigm, by having Lightray transform the hideous “Caller” thing into a glistening apparatus, somewhat resembling an automobile engine.

As the earlier incarnation of the creature is a mass of protruding tendrils, the new form is in the words of one of the characters, “shooting strange machine-like forms through the walls and decking of this ship.”

Lightray describes the process that he had affected as “techno-active.” This is indeed a good description of the artistic evolutionary process that Kirby has undergone. If we look at his earliest work, we can see that the very preoccupation with technology that started in his youth has over a thirty year period also made the artist Techno-active.

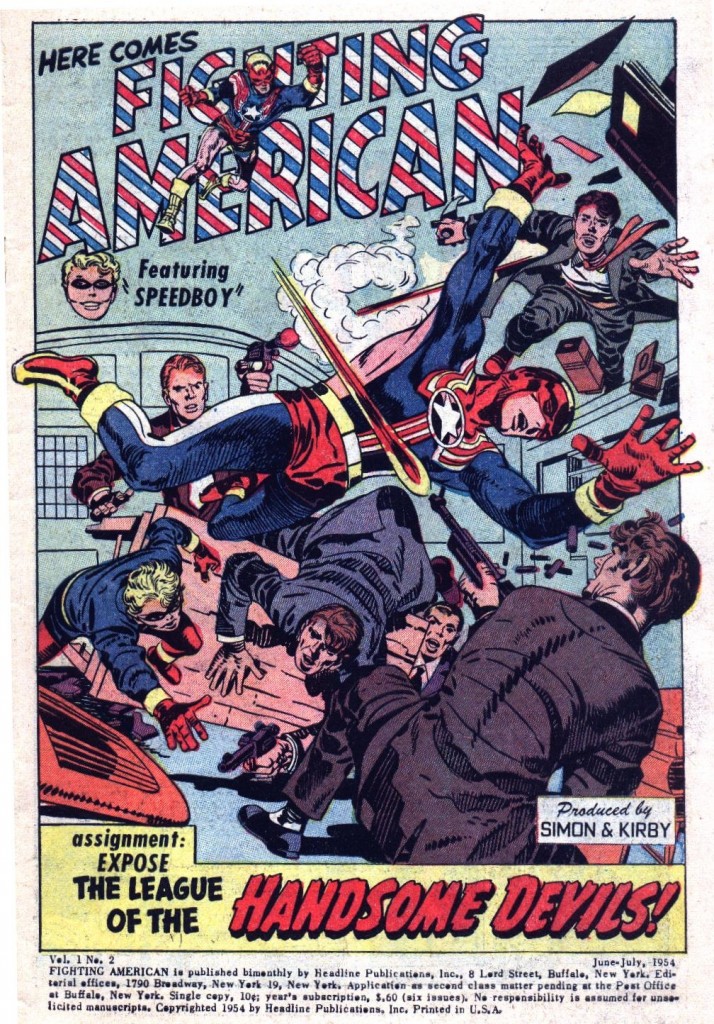

Image 1- Real Fact Comics Jack Kirby, Joe Simon 1946 reprinted in Jimmy Olsen #145

Image 2-Newsboy Legion, Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, reprinted in Jimmy Olsen #145

Image 3-Fantastic Four #72 cover, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Joe Sinnott

Image 4- New Gods #6, Jack Kirby, Mike Royer

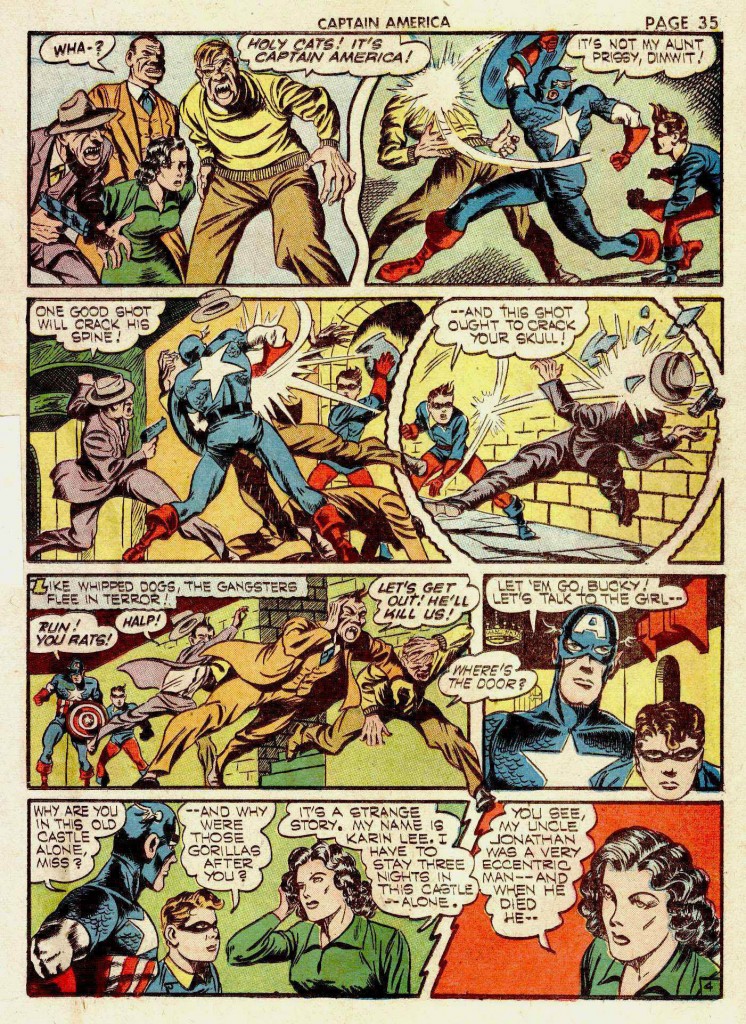

Image 5-Ibid