Fantastic Four #4 was probably the first comic book that actually opened my mind to the possibilities of the comic art medium. I’d picked up on the series with issue #12, and was instantly hooked on the self proclaimed Worlds Greatest Comic Magazine. I began searching around for back issues and was lucky enough to have a good friend loan me issue #4. As wonderful as they are, there is something slightly rushed and desultory about the first two issues of this series. Perhaps the innovation of costumes in the third issue started to get Kirby jazzed, but in FF#4, with the re-introduction of Timely’s second Golden Age star, the Sub-Mariner, Kirby really begins to hit his stride.

The story begins powerfully, with three members of the team arguing about the disappearance of the fourth. Reed is chastising Ben about the latter’s jealousy over Johnny’s exploits in the previous chapter. It is Ben’s bad attitude that has caused the Torch to quit the group. By now it is clear that it is the Thing’s brooding resentment over his condition that provides the dynamic chemistry that sets this series apart. It is also clear that this is not a simple tale of good guys vs. bad guys and that Kirby and Lee are dealing with serious issues of emotional turmoil and the dynamics of relationships within a family, such as parental authority and sibling rivalry. The members of this team are obviously a surrogate family, working out their problems, and the plot is merely what Alfred Hitchcock would call the McGuffin, a device to set the characters in motion.

The three go in search of the Torch, who is hiding out in a local garage with his sport’s car pals. Kirby is clearly beginning to stretch out with the Fantastic Four as a sequential story teller now. He is using more of a full palette of continuity techniques herein.

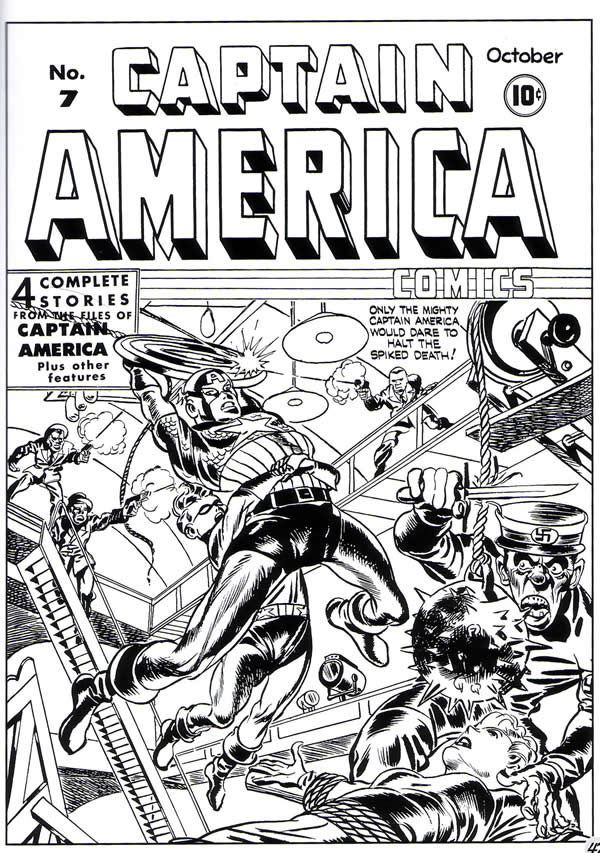

1

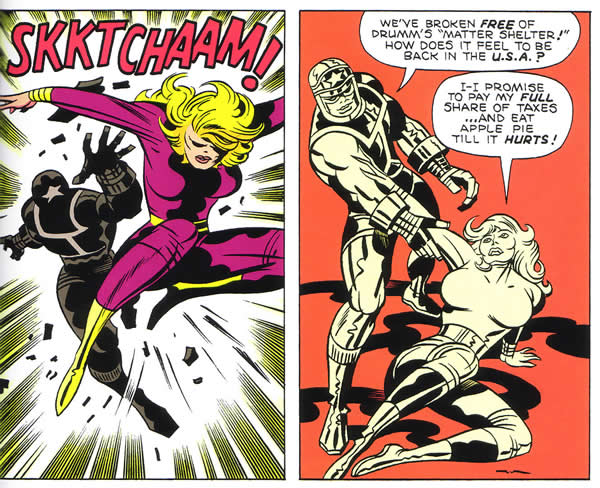

In his unparalleled study of the genre, Understanding Comics, author Scott McCloud describes various transitional techniques used in sequential art. Generally, the most common of these in western comics is subject to subject, an example of which would be the last four panels of page five in FF#4 above, wherein the artist’s point of view is confined to the same general scene, but is moving from the subject of the Torch to the subject of the Thing. However, the upper tier of panels is a different story. This sequence would be best described as moment to moment or action to action, a technique that Kirby excelled at, which makes sense considering his early training in animation. Here in three continuous action panels, the Torch is shown igniting his finger and welding an auto part.

Two pages later, the same technique is used showing the Thing, who has just cornered Johnny in said garage, suddenly changing in a four panel sequence back to Ben Grimm. If there is any confusion about the editing techniques I am describing, one simply needs to think of a cameraman, choosing either to maintain the position of his camera and shooting a scene in a continuous sequence, or cutting away from a shot to another shot or another aspect of the same shot.

One can easily see that drawing sequential art often offers similar challenges to storytelling as does filmmaking in it’s arrangement of sequences.

2

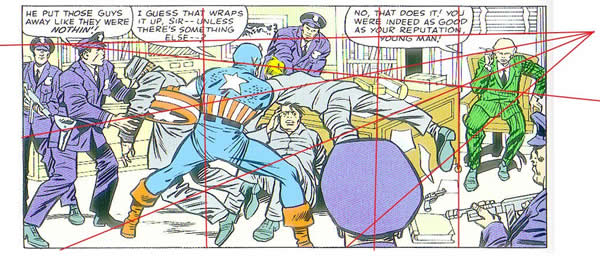

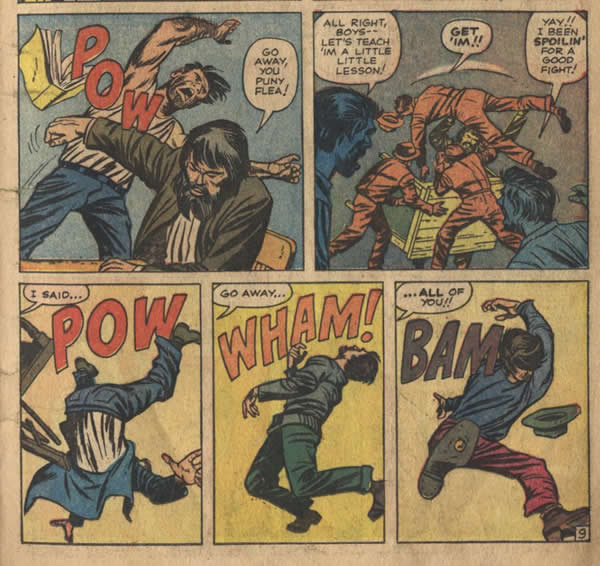

The Torch eludes the Thing and goes even deeper undercover. It is at this point that this episode begins to delve into the murky waters of mythology as it is related to the human psyche. The Torch’s next stop is the Bowery, a stone’s throw from Kirby’s own lower east side roots and in the artist own recollection, a virtual urban heart of darkness. In two amazing panels, Kirby establishes mood and setting, as Johnny is seen walking down a forlorn street and stopping in front of a fleabag hotel.

In panel two of this page in particular, Kirby sets a scene of a street of desolation with the placement of the shabbily dressed figures loitering on the sidewalk. The age and decrepitude of the run- down buildings is indicated by the wrought iron stanchions on the stairway and that of the post that the seated figure is leaning against.

3

This small panel is a beautifully composed deep space scene, with multiple visual cues to suggest that Johnny is enveloped by the misery that surrounds him.

Johnny’s thought balloon refers to the street’s inhabitants as “human derelicts”, an obvious nautical reference to abandoned ships. While reading an old comic book in his hotel bed, Johnny is introduced to the derelict of the ancient (Sub) Mariner, bearded and incoherent

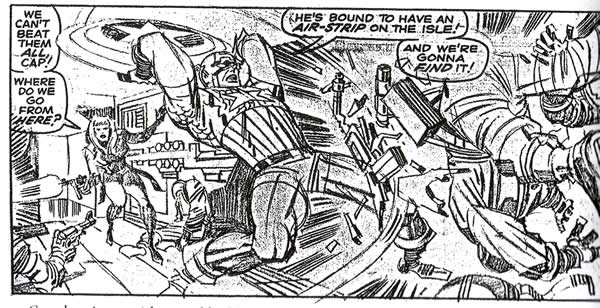

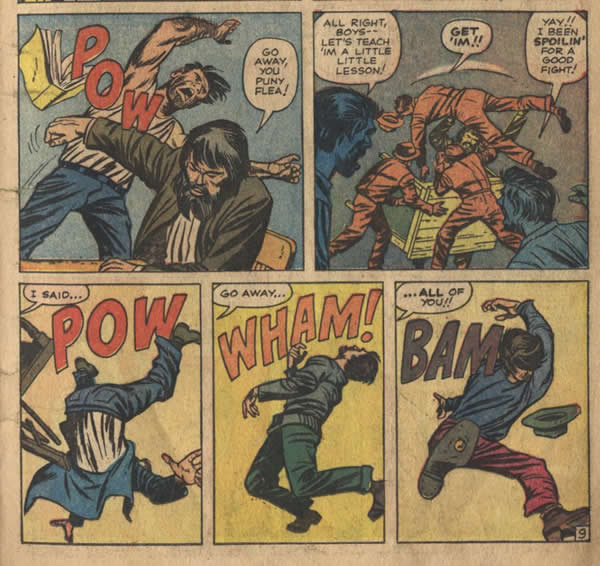

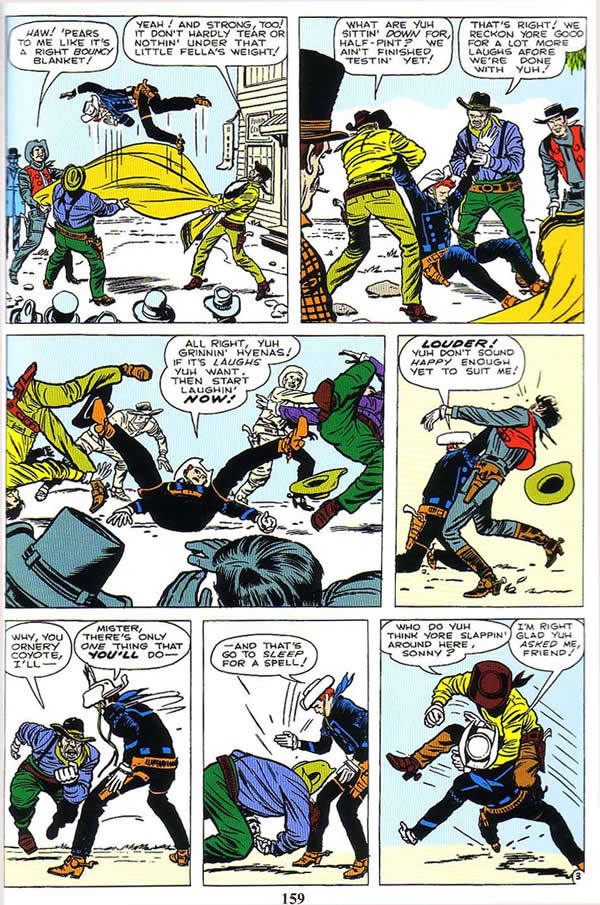

When the ill mannered vagrants bait the befuddled Namor, Kirby reveals the hero’s awesome power in an unforgettable sequence. Although the continuity of this tier of three panels suggests that it is an action to action sequence, it is actually an unusual example of subject to subject artwork. One does not see Namor’s initial action as he assaults the men, only their reaction as they are tossed away like so many broken toys.

4

As a boy of eleven, I was completely mesmerized by the way these tumbling figures were rendered, particularly in the first panel where the man is going heels over head and the third figure whose shoe sole is coming towards us. The panels serve as a perfect triptych of continuity of gesture. The leg and hand of the first figure lead us into an almost hieroglyphic series of balletic commotion.

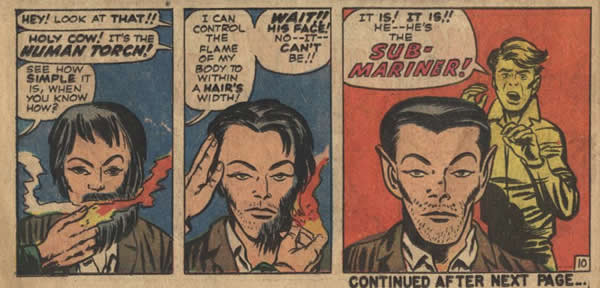

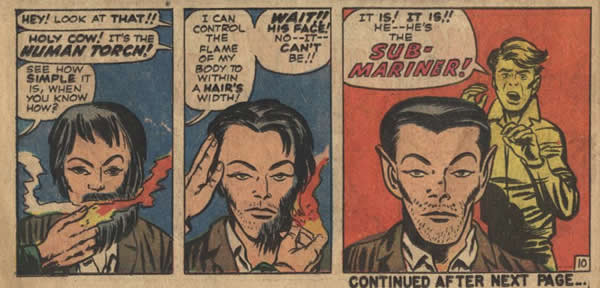

Johnny breaks up the ruckus, and in a dramatic moment to moment sequence reminiscent of the earlier welding scene, he shaves Namor’s beard and reveals the face of the Sub-Mariner.

5

Next, by throwing Namor into what is presumably the East River, (the subconscious) Johnny restores the Sub-Mariner’s identity. The light of the Torch has descended into Hades to retrieve the fallen aquatic hero. Thus does the Golden Age Dynamic Chemistry of fire and water re-assert its self. With this action, the Silver Age is truly born. (Two years later, Namor completes the circle by releasing the frozen Captain America.)

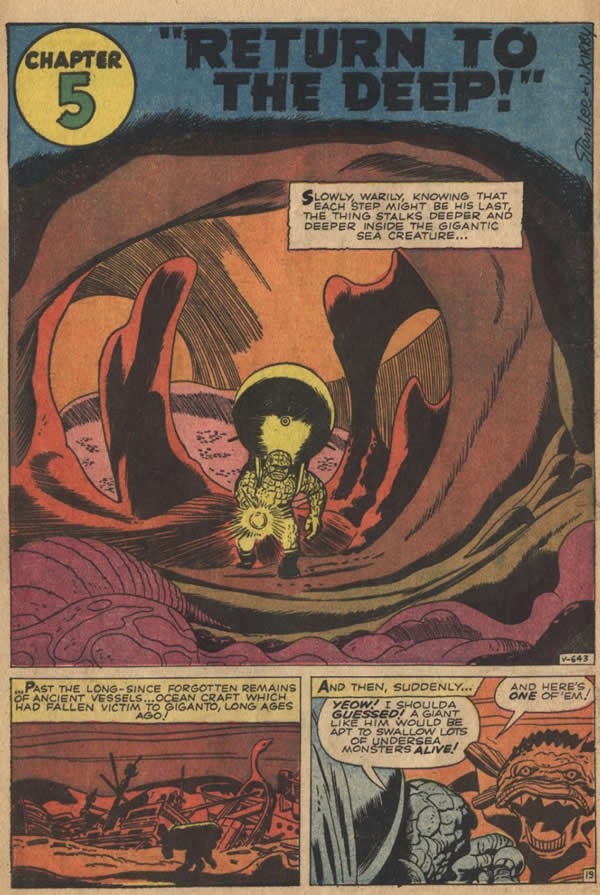

Prince Namor next swims to an outpost of his former undersea kingdom, only to discover that mankind’s nuclear program has destroyed much of his civilization and driven off his subjects. The Sub-Mariner vows to exact vengeance on humanity by unleashing a monstrous Atlas era Kirby creature, a huge leviathan of a four legged whale called Giganto.

To atone for his sin of anger, the Thing must descend into the mythical belly of the beast, in an effort to destroy the monster, which is clearly another hero’s journey into the underworld and the realm of the subconscious.

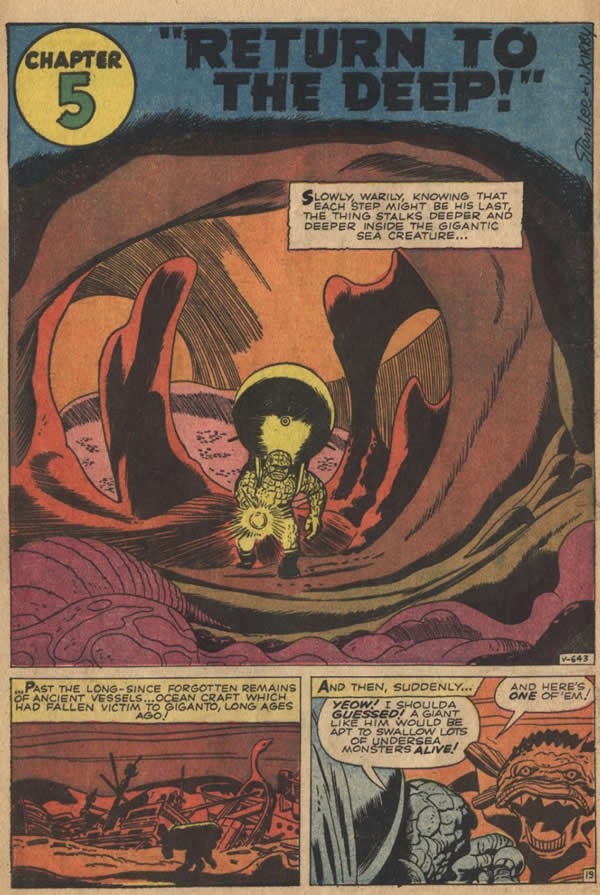

What is wonderful about the first dozen or so issues of the Fantastic Four is the division of the stories into chapters, giving Kirby the opportunity to flex his artistic muscles in three quarter page panels. Thus, in this issue, there is the spectacular tableau of the opening of chapter five, showing Ben trudging through a cavernous hell within the bowels of the great creature, with a massive bomb strapped to his back. The page is beautifully drawn, with dramatic shadows, illuminated by the flashlight that the Thing is carrying. In the lower left corner is a strange organic shape suggesting viscera of some sort. The page is well colored in lurid violets and reds that add drama to the scene.

6

Ben successfully dispatches Giganto and returns to the land of the living. The Four again confront the defiant Sub-Mariner, who threatens to summon even more creatures with his trumpet, but the horn is suddenly snatched away by the Invisible Girl.

When he chases her down, Namor is smitten with love for Sue Storm. It is here that Namor resumes his career as more than just an antagonist to the Fantastic Four.

7

Considered to be the comics first true anti-hero, the Sub-Mariner has always been a complex and conflicted character, half aquatic, half human, arrogant, charismatic and imperious. If the F.F are elementals, with the Human Torch as fire, the Thing as earth, the Invisible Girl as air and Mr. Fantastic’s flexibility representing the liquidity of water, then Namor, as ocean monarch is an obvious rival for Reed Richards in a love triangle for Sue’s affections. Although introduced as a villain in F.F.#4, Namor is a wild card who over several years will continually be played as either friend or foe. In the final scene, his love for Sue is initially rejected, although when Namor next appears in a later issue, it seems that the fickle nature of Susan Storm has begun to warm to the notion of a tryst with the undersea prince.

In the conclusion of this story however, Namor rants and raves on about destroying mankind with a plague of undersea creatures, whereupon quick thinking by the Torch provides a solution in the creation of a tornado which deposits the Sub-Mariner and his dead whale back in the ocean.

Namor, while spewing a torrent of curses in the general direction of the surface, wisely decides to remain below. It is obvious that such a powerful and enigmatic character will be seen again soon.

This issue essentially initiated the Marvel Age trend of including new and old characters in multiple crossover appearances in other issues of the company’s titles.

Namor, as prince of Atlantis is the first in a series of astounding beings who hail from another world that exists within our own. His example would soon be followed by Kirby’s creation of such alternative super societies as the Inhumans in their Great refuge. Over time, Kirby would continue to explore the theme of various parallel universes that exist alongside or around us.

As the Atlas Comics website states of Kirby, “He is the unquestioned king of invention; not just characters, but devices, stories, races and worlds.”

Although Kirby didn’t invent the Sub Mariner or his sunken realm of Atlantis, this singular fourth issue of the Fantastic Four is truly the beginning of the King’s use of Dynamic Chemistry in the Marvel Universe, with his vivid imagination spawning legions of amazing characters whose worlds intersected with our own.

All images from Fantastic Four #4

Story and art by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby