When Jack Kirby’s Fourth World epic began to falter, the King considered less ambitious, more commercial projects to spark his career. Kirby used the film Planet of the Apes as a jumping off point for the series Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth, populating his post apocalyptic world with a plethora of sentient animals and a human race composed predominantly of inarticulate brutes. While Planet of the Apes was a fairly serious scathing indictment of the folly of mankind’s penchant for war and its potential consequences, Kamandi was in comparison a lighthearted romp that still managed to satirize the inhumanity of seemingly intelligent sentient beings vying for ascendency on planet Earth.

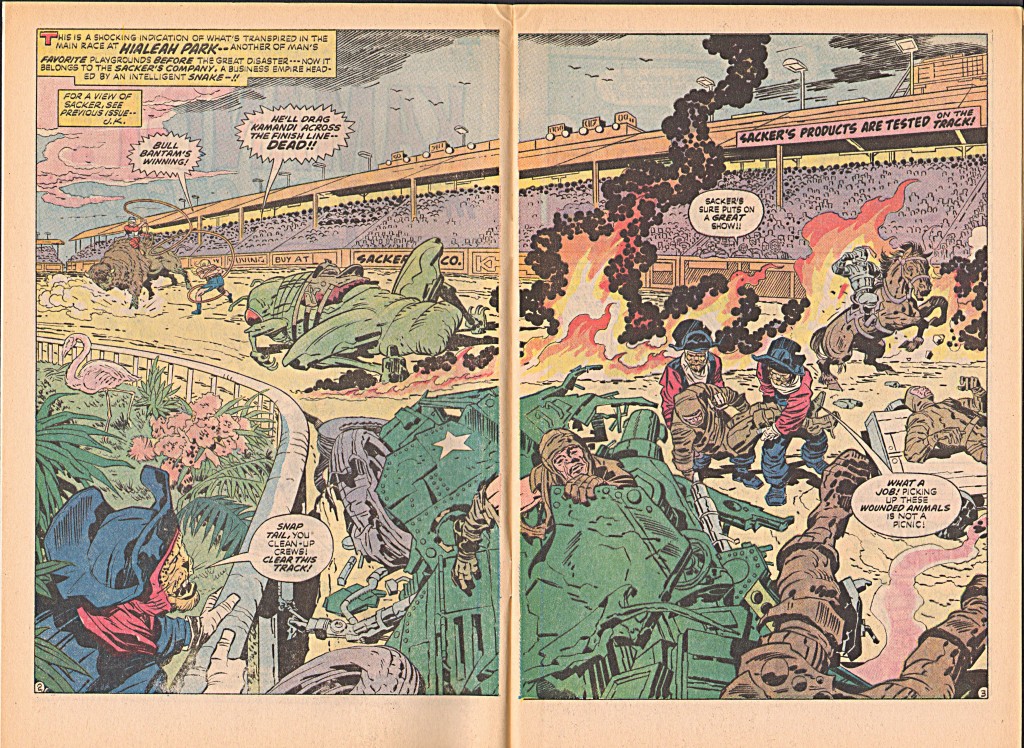

One of the most memorable episodes in the series climaxes in issue #14. Kamandi, a teenage boy captured by anthropomorphic leopards is forced to engage in a life and death race against a brutal human Bull rider. Kamandi’s mount is Kliklak, a giant cricket with which he has developed a strong emotional bond. This is an explosive action filled comic, which uses space in Kirby’s typically expressive panoramic way. This wonderful spread is a shot of the racetrack at Hialeah following a savage race.

The broad left to right sweep of the stadium roof is broken by the smoldering flames, which draw the viewer’s eye to the wrecked vehicle and then to the huge cricket. The leopards carrying the body also allow the eye to move around and back to the leopard holding the railing on the left. The sense of space and movement in this spread is truly astounding. It is another of Kirby’s space/time continuums that he does so well, giving the cinematic illusion of the passage of time in a single still frame.

On page eight, the thuggish Bull Bantam and his buffalo charge at Kamandi and Kliklak with devastating effect, as shown in the horizontal third panel.

The screaming, gaping jaws of the various creatures in panel two connect visually with the impact lines emanating from the buffalo’s battering ram of a head in the long panel below it. The blood-thirsty savagery of the bestial spectators presages the savagry of Bull Bantam’s attack.

This is to me one of the most pathos filled moments in a comic book, as we see the wounded insect staggering helplessly, attempting to recover from his injuries

Charging Kamandi, the bison rider throws a grenade, and in another wide middle panel, the giant cricket leaps towards the viewer and away from the deadly explosion.

The King always makes the most of depicting any form of force or expended energy, and in this case, the concussive clouds and force lines behind Kliklak propel him at us with maximum velocity. The insect’s hyper extended legs add to the dynamism of the panel, as does the arc of the WHAM sound effect. Kliklak lands in a heap, mortally wounded.

In a bravura panel, Kamandi leaps directly onto the head of the charging buffalo. Any normal attempt to draw this moment realistically would almost certainly not be as effective as Kirby’s expressive exaggeration. He is at the height of his powers and confidant enough to wing it. The skewed anatomy in this drawing doesn’t detract from its power and directness. Kirby and Kamandi are literally grabbing the bull by the horns.

Kamandi dispatches Bull Bantam in a fight sequence that I’ve already lovingly described in a previous blog post. (See Rawhide Kid, The Black Spot) Kirby is playing with themes here, combining a classic Western rodeo with a racetrack setting. As the classic cowardly bully, Bull Bantam gets his comeuppance. Kamandi then turns to the crowd and admonishes them for their callous brutality.

The suffering of his insect friend devastates Kamandi, and his pain and rage are palpable. When one of the leopards is about to put Kliklak out of his misery, Kamandi intervenes. He chooses to end the suffering of the pathetic creature himself.

For those who are critical of Kirby’s story-telling abilities and characterization skills, I present this poignant fragment. Kirby has given us an insect, a creature whose only form of communication is body language and the sounds it emits. It is remarkable that we are capable of caring more for this strange animal than for most of the vapid, overly dramatic and self-absorbed super-heroes that currently inhabit the various comic book universes. This is what sets Kirby apart.

Long live the King.

All images from Kamandi #14 Jack Kirby and Mike Royer.

Thanks to Mike Hill for his scans