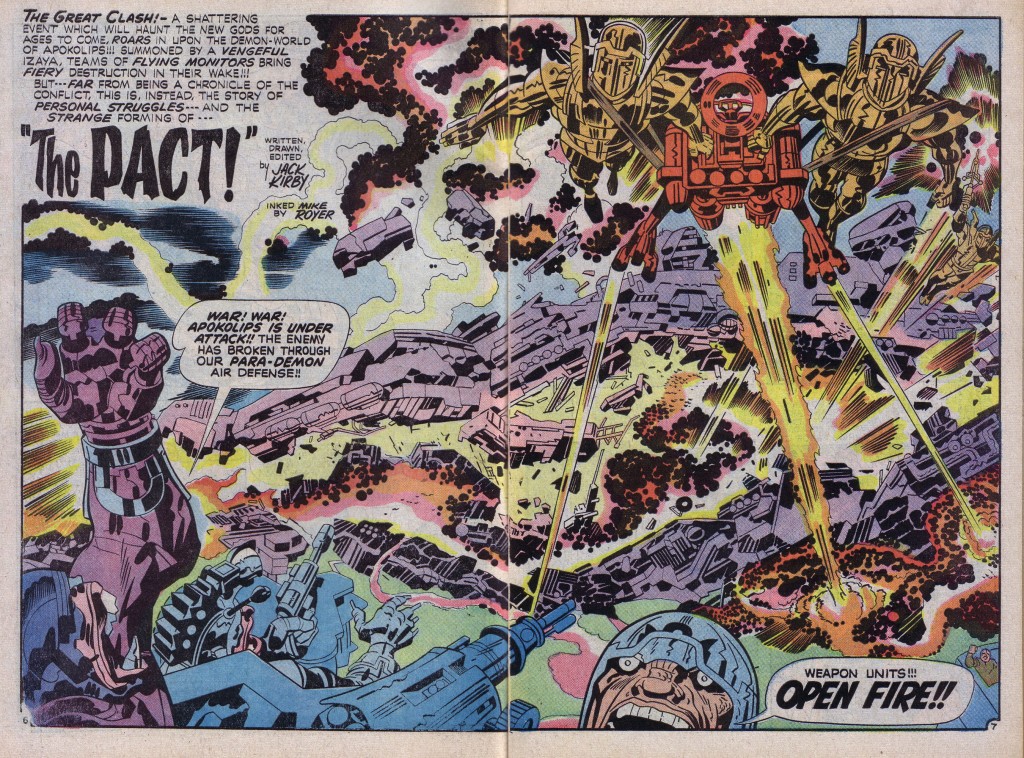

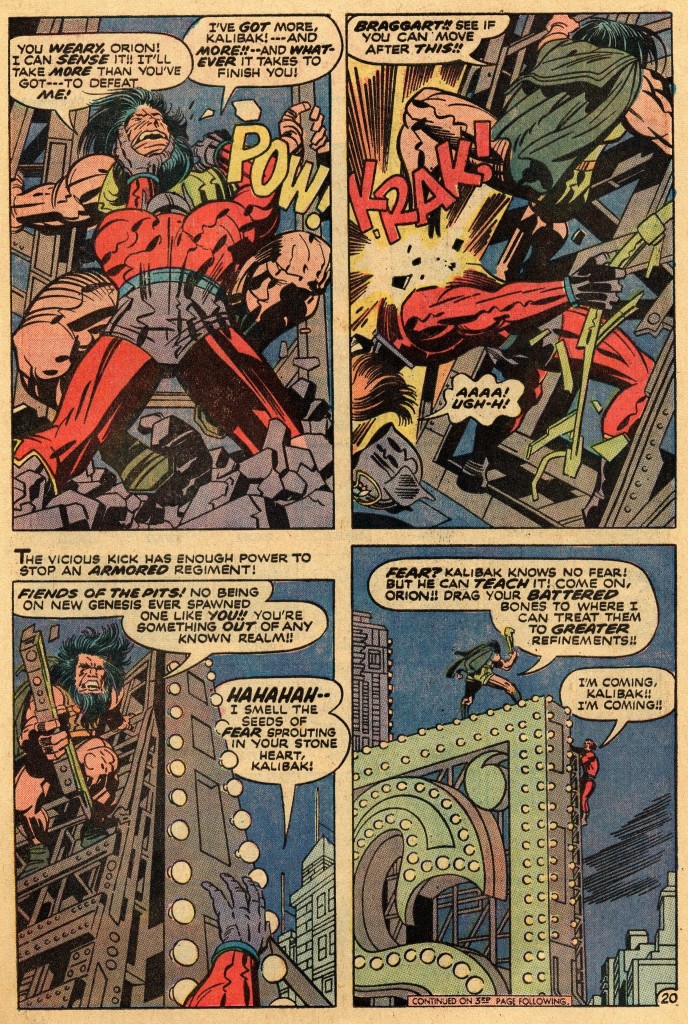

I’d like to change the focus this time and discuss Kirby’s creative process involving collaboration in greater detail. From what we know about the King, he was generally happiest working more or less independently of other writers. However, there are many who believe that Kirby’s best and certainly most commercially successful work was in collaboration with writer Stan Lee. There has been a good amount of ink used discussing just who did what in that process.

In conventional comic production involving a separate writer and artist team, the writer provides the artist with a full script to work from. Lee is famous for having instituted the Marvel Method, wherein an artist would plot a story based on the sketchiest of outlines provided by the writer. Once the story was drawn the artist would supply the writer with explanatory notes in the page’s margin, whereupon the writer would fill in the final script. Lee believed that his artists were strong plotters and allowing them creative freedom would result in a better story. Certainly, in the case of Jack Kirby, he was correct.

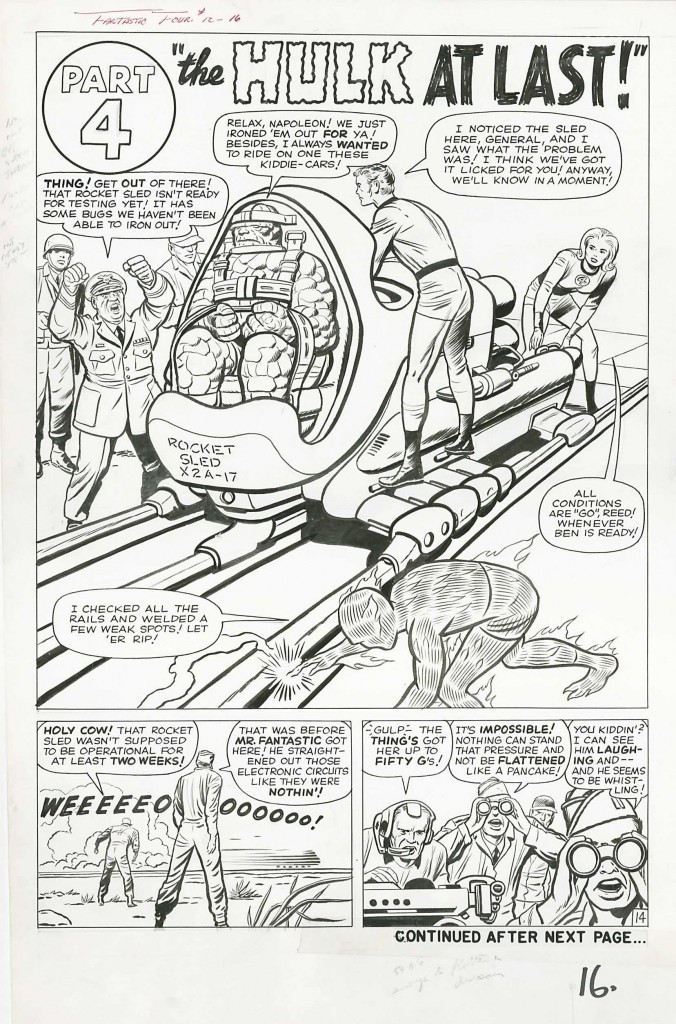

Recently, I saw a film clip of Stan Lee looking at Jack Kirby’s original artwork for Fantastic four #12 for the first time since it had been published. One of the first things that caught Lee’s eye were the margin notes in the panel borders, that he initially assumed belonged to Kirby. Lee started to explain the Marvel Method of writing, wherein he would give Kirby a rough idea of the plot, Kirby would elaborate the plot, pencil the book and deliver to Lee with Kirby’s notes for scripting in the margins. Halfway through his explanation, Lee realizes that the margin notes are his own, written as reminders to him, prior to final scripting.

This exchange raises an interesting question. Just when did the process known as the Marvel Method actually begin and what was the nature of the creative process prior to its inception? Several Comic Book historians allege that in the beginning, Stan Lee provided his artists with full scripts. Lee’s brother, Larry Lieber has stated in interviews that he wrote full scripts for Kirby as well. However, Kirby and several of his co-workers claim that the King seldom followed scripts to the letter, either using them as a jumping off point or discarding them completely.

This would partially explain Stan Lee’s need to write margin notes for himself on Kirby’s artwork. If Kirby commonly changed the direction of the story given him, Lee would require more than his original script as a guide. He would, in effect need to re-script the story after receiving it from Kirby in order to accommodate the artist’s alterations.

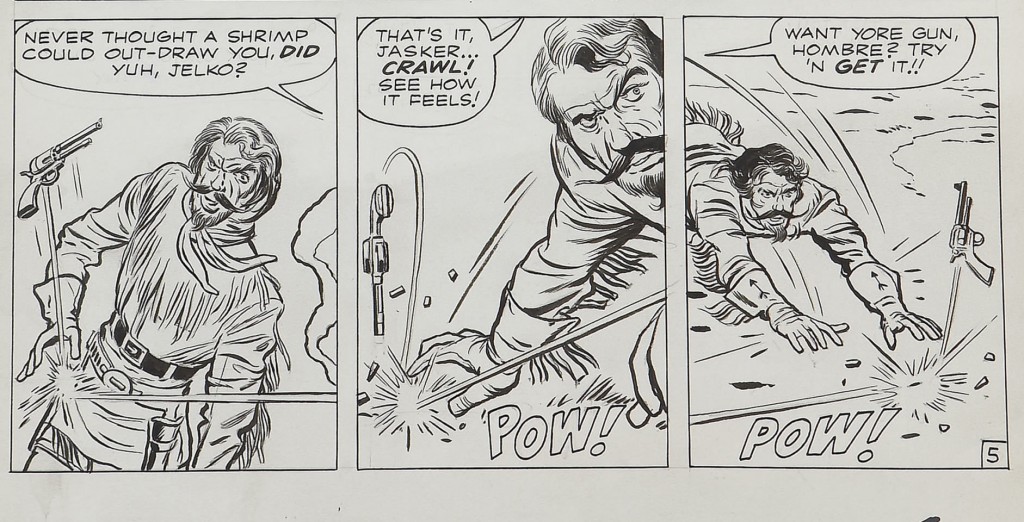

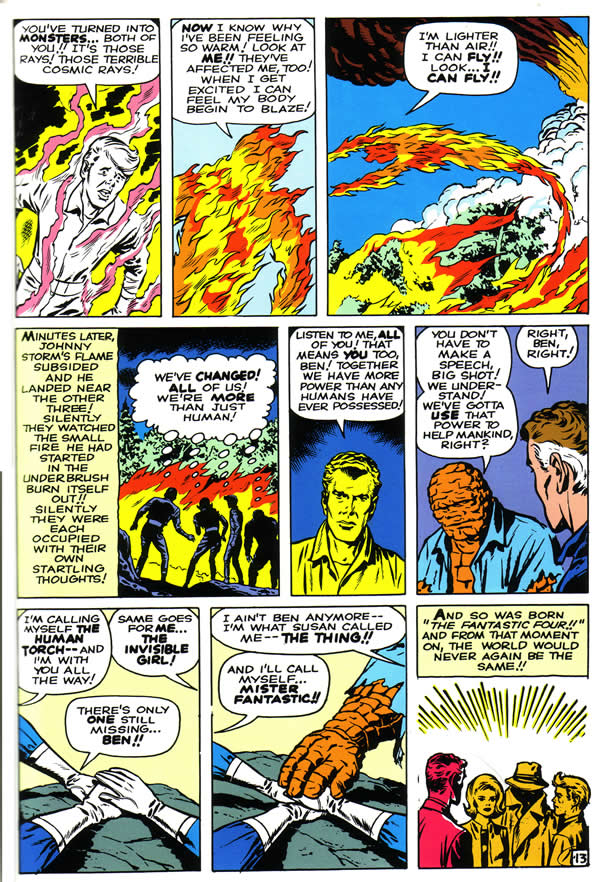

Until we are presented with a complete Lee/Kirby or a Lieber/Kirby script and a story to compare it to, we cannot be sure how completely Kirby followed their scripts. What we do have is a fair selection of original art from that period. This page is from Fantastic Four #12, the issue that Lee was perusing on camera.

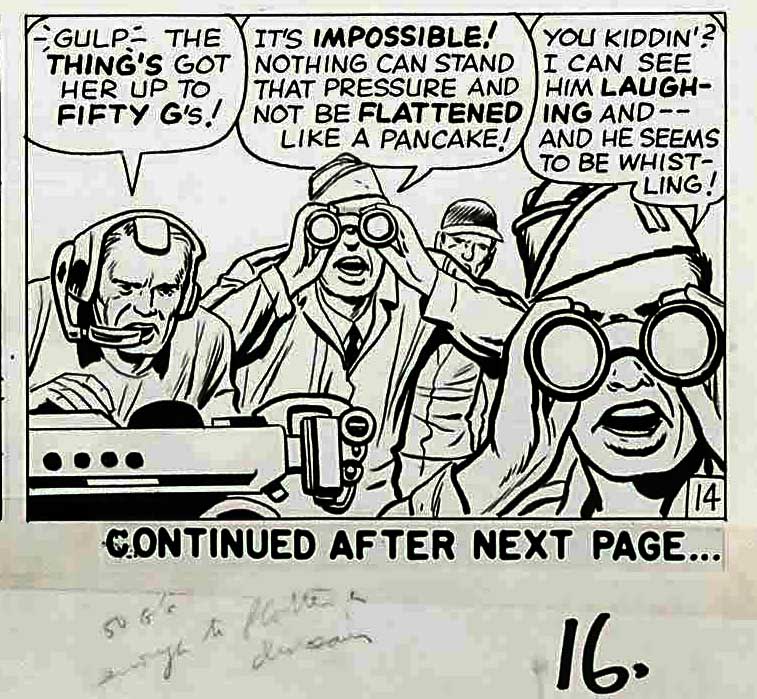

If we study Lee’s margin notes, we generally see that they say more or less what he will later elaborate in the balloons above: The scribble below saying “50 G’s, Enough to flatten, et cetera” has become two balloons spoken by separate characters.

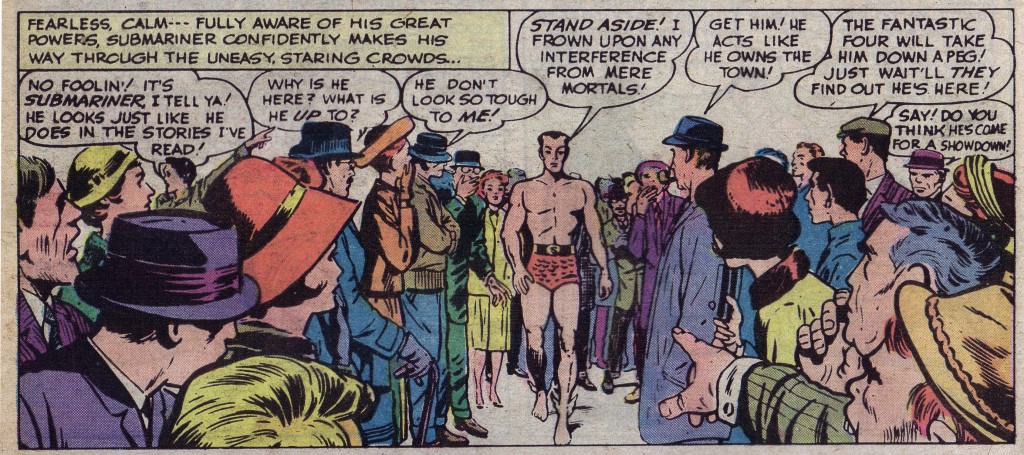

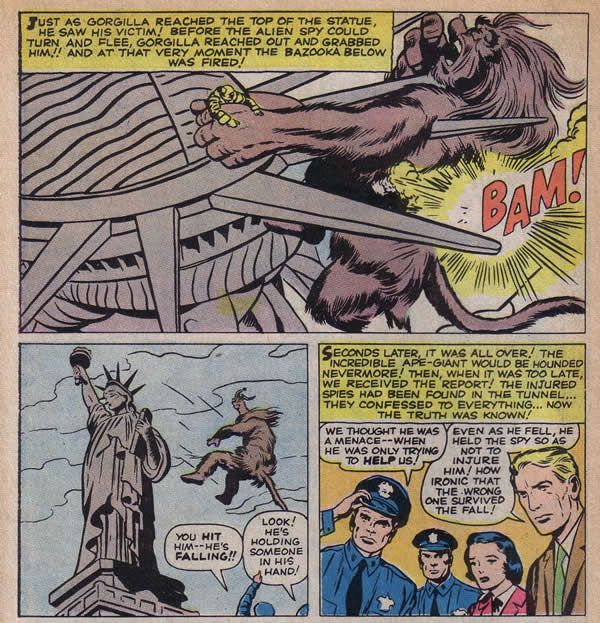

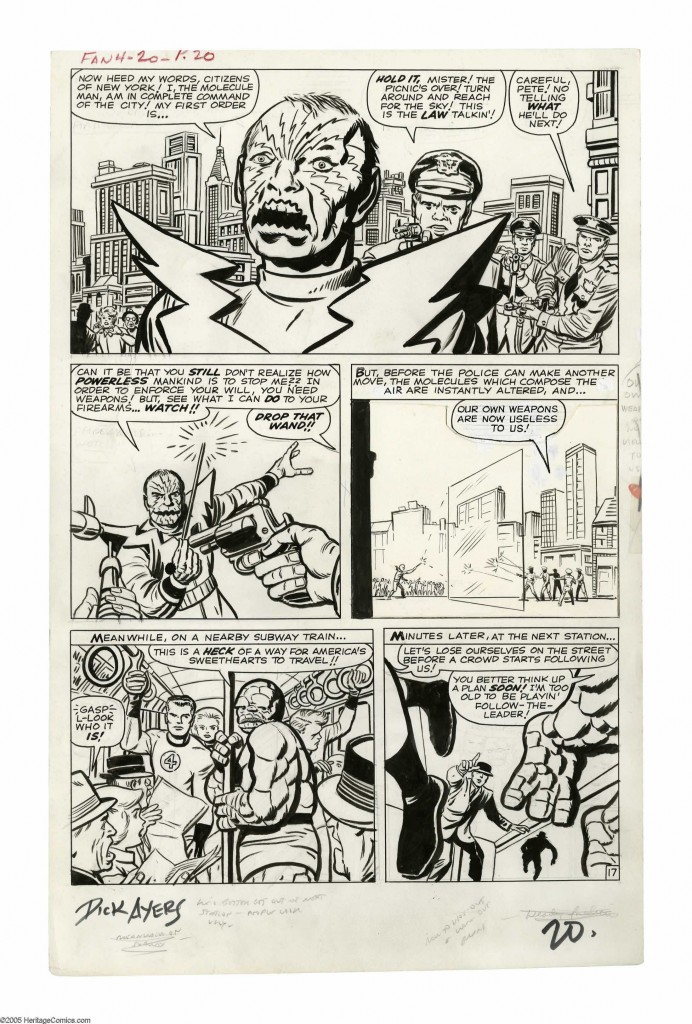

On this page in Fantastic Four twenty, we still see Lee’s margin notes, so we can assume that the Marvel method has not yet gone into effect. What we do see is something exceedingly interesting. Notice that the third panel is drawn by another artist, which is almost certainly Steve Ditko. This is a case of a last minute change being made in the story prior to printing.

Comic Book historian, Bob Bailey states that Kirby was probably not available to make the change and Ditko was on hand. Therefore, he re-did the panel.

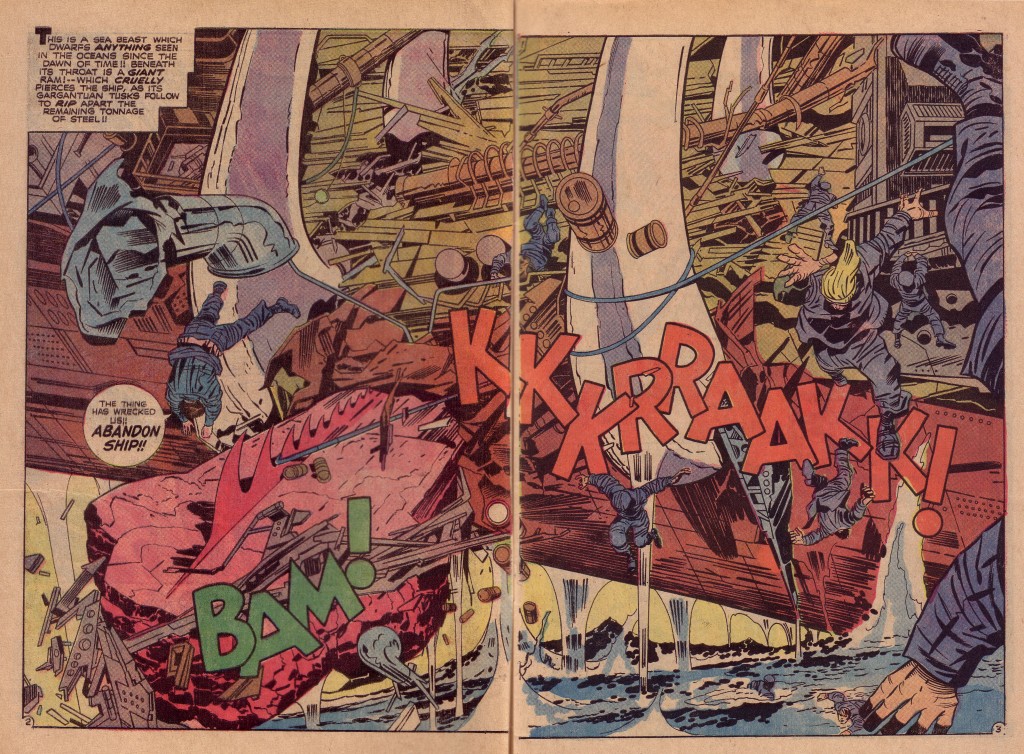

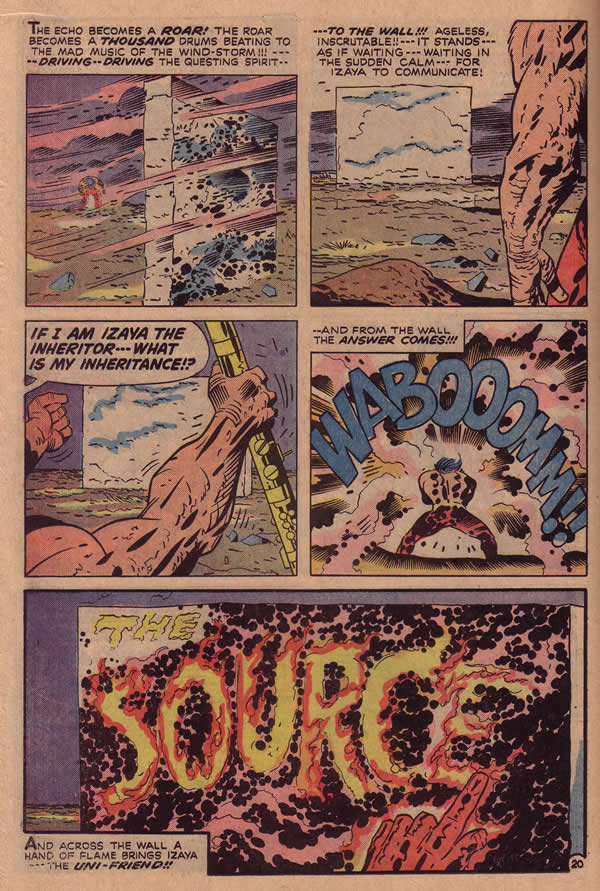

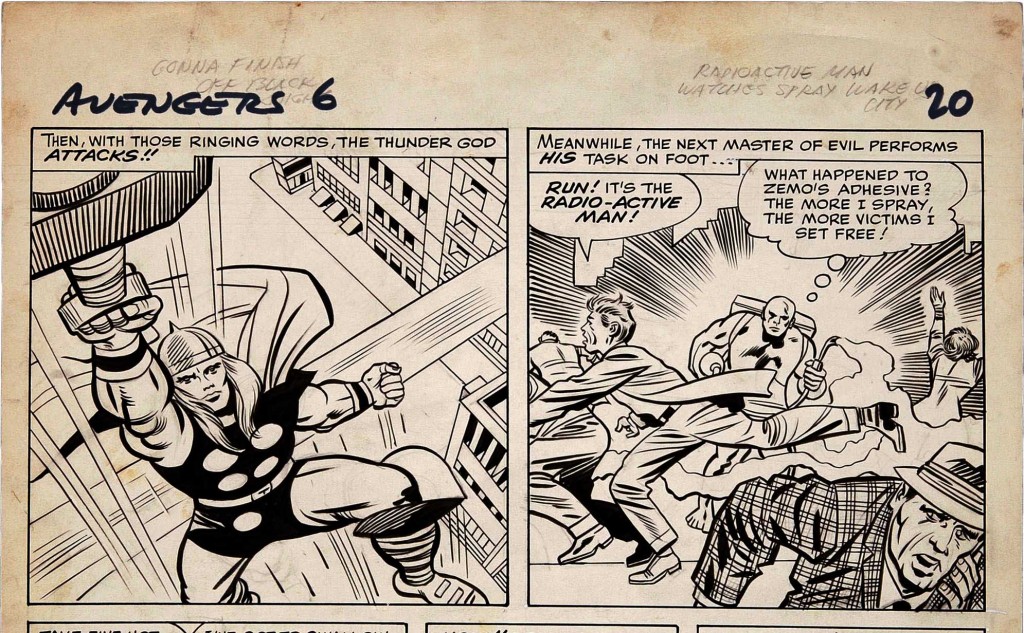

The earliest Fantastic Four page scan that I can find with Kirby’s notes is from F.F. Annual #2, appearing in the summer of 1964. Comic Book historian, Nick Caputo concludes that the Jack Kirby’s margin notes first appear in The Avengers #6, dated July 1964. If one looks at the notes in the upper margin, it is clear that it is Kirby’s lettering. Thus we can probably date the beginning of the Marvel Method to this approximate period.

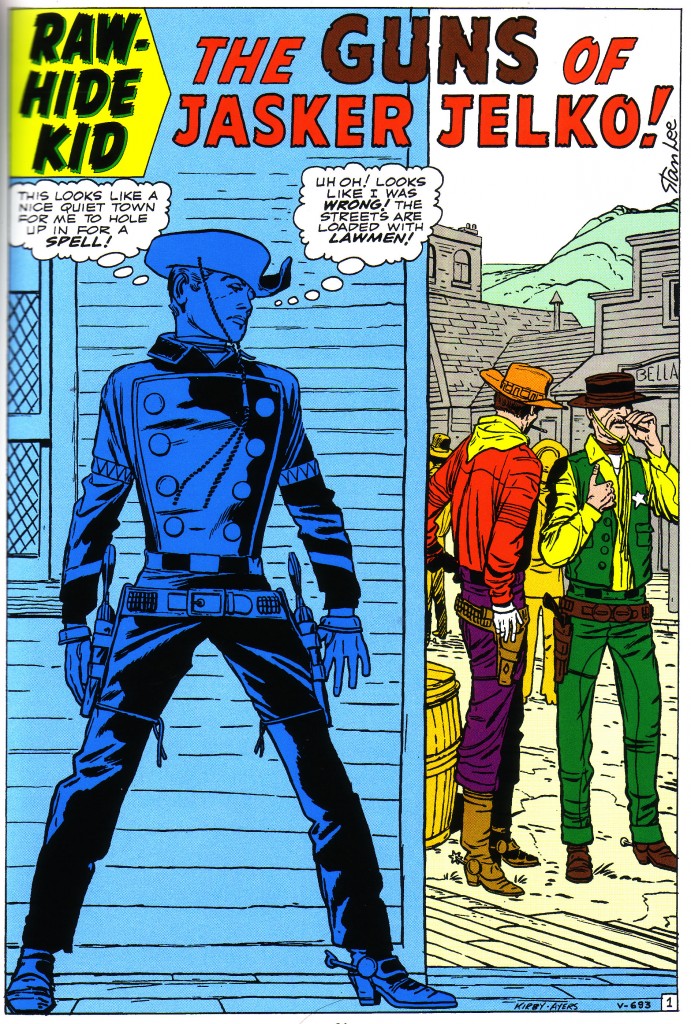

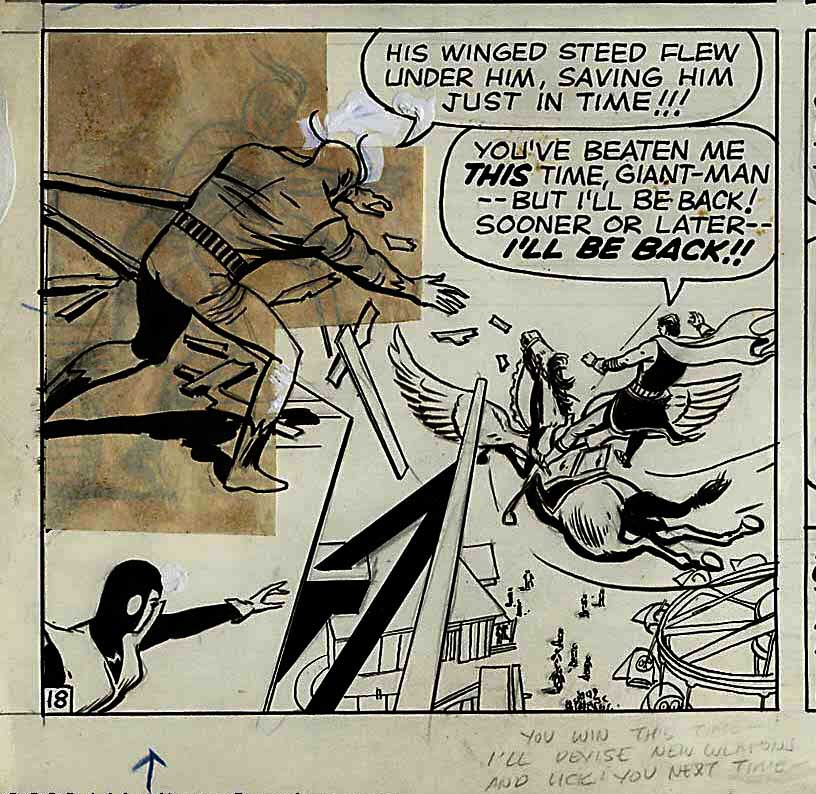

Nick Caputo also says that artist Dick Ayers claims that he in fact was the first artist to provide notes for Stan Lee early in 1964, as this Giant Man panel from that year suggests.

Caputo: “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Stan took over the hero strips three months earlier, providing plot synopsis’ for Dick Ayers and Don Heck for the first time. Before this they were working from full scripts provided by Robert Bernstein, Ernie Hart and Larry Lieber. Stan’s notes are seen in Avengers # 5, so apparently sometime between May and July 1964 dated issues Jack began adding notes, likely at the request of Lee. I’ve seen Bill Everett’s notes on the original art of Daredevil # 1, which appeared three months earlier, so it is highly likely that Heck and Ayers began around the same time or earlier.”

The question still remains. What precisely was the method used for constructing stories prior to the inception of the “Marvel Method’? In most cases one can be fairly certain that full scripts were used. Kirby is another case entirely.

We’ll give Kirby historian and biographer Mark Evanier the last word. It is probably not a great leap of logic to apply this description to other writer’s scripts as well.

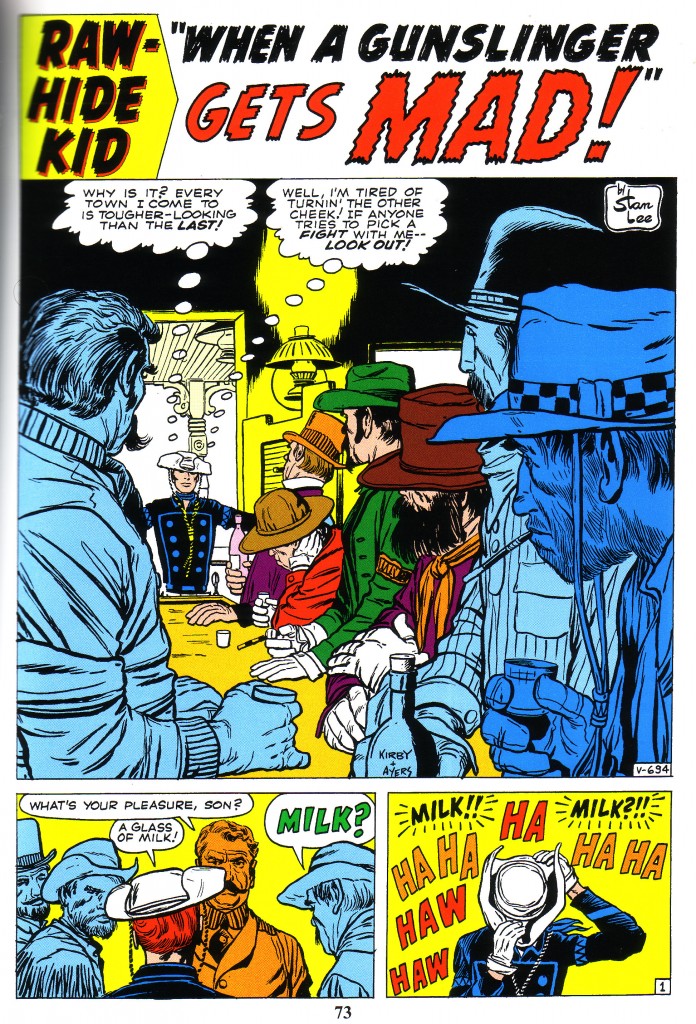

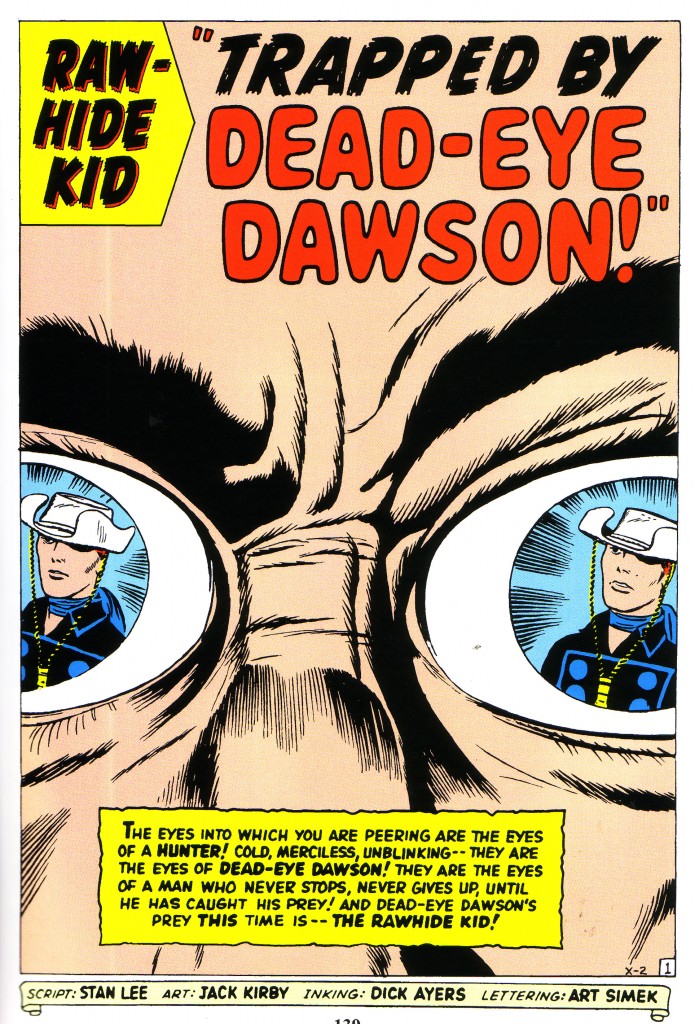

“As for who plotted the monster stories scripted by Larry Lieber, that’s one of those cases where Stan says one thing and Jack said another. Apparently, Jack would give Stan a lot of plot ideas and then Stan would select what he liked from the verbal pile. Based on talking with Stan, Jack, Larry, Don Heck, Sol Brodsky and Don Rico, I would say that Jack plotted some, Stan plotted some and a lot were Stan polishing a Jack idea. Then the whole thing was handed to Larry, who would write a script. And then Jack would fiddle a lot with the scripts.”

Sounds like a reasonable explanation to me.

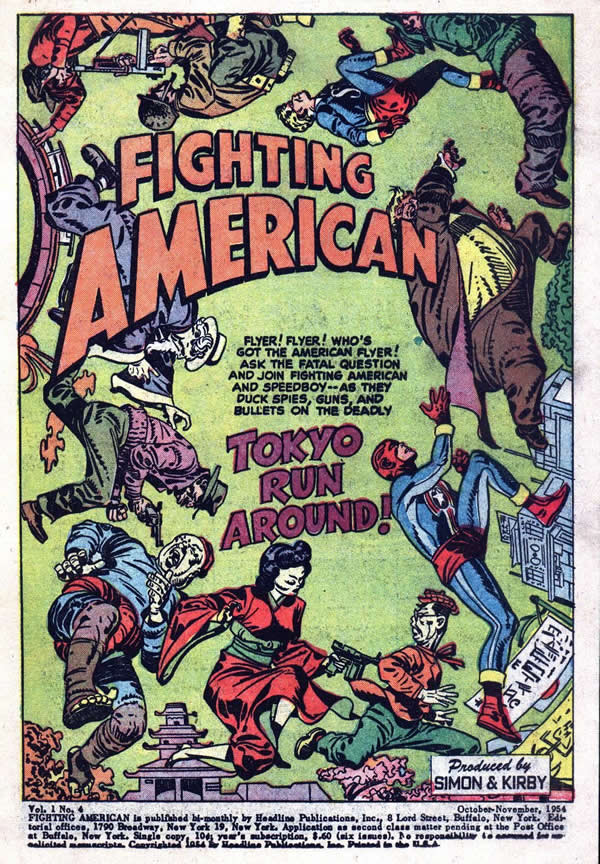

1-Fantastic Four #12- Stan Lee, Jack Kirby

2-Ibid, detail

3-Fantastic four #20- Stan Lee, Jack Kirby

4-Ibid, detail

5-Avengers #6 -Stan Lee, Jack Kirby

6-Tales to Astonish #52-Stan Lee, Dick Ayers