For this summer entry, I am re-editing a post from last fall, because I recently acquired some actual scans from Hulk #1 to use in place of the Masterworks book versions. Since this particular book had such a profound impact on my emerging appreciation of Kirby’s art, I thought that I would re-present the post with some additions and revisions. Crucially, The Masterworks books were re-colored, in an attempt to make the art look more sophisticated, but for me a good portion of the visceral power came from the stark simplicity of the coloration, which was essentially done that way to save money. That crudeness became a part of my vital memory of the initial impact of the comic.

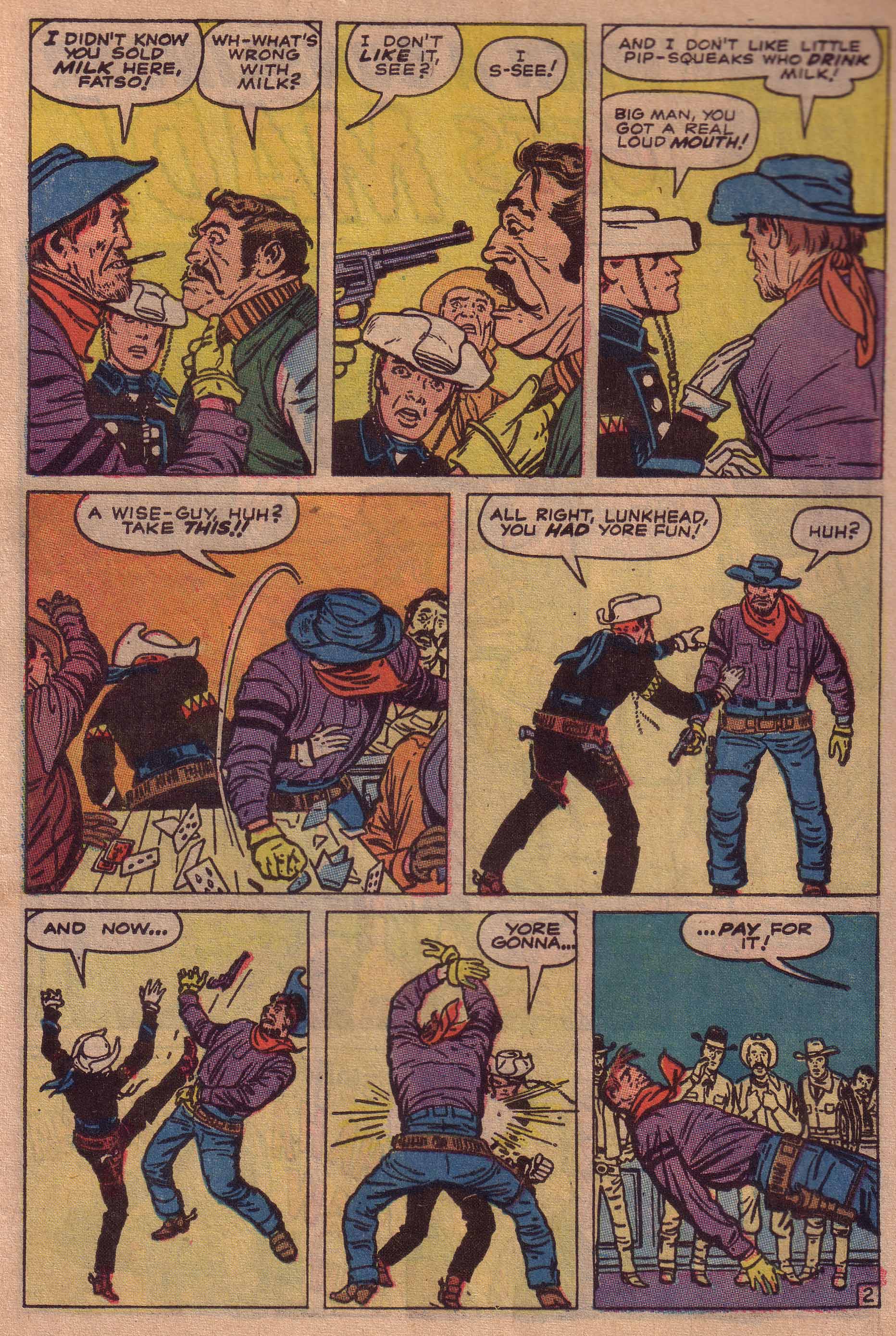

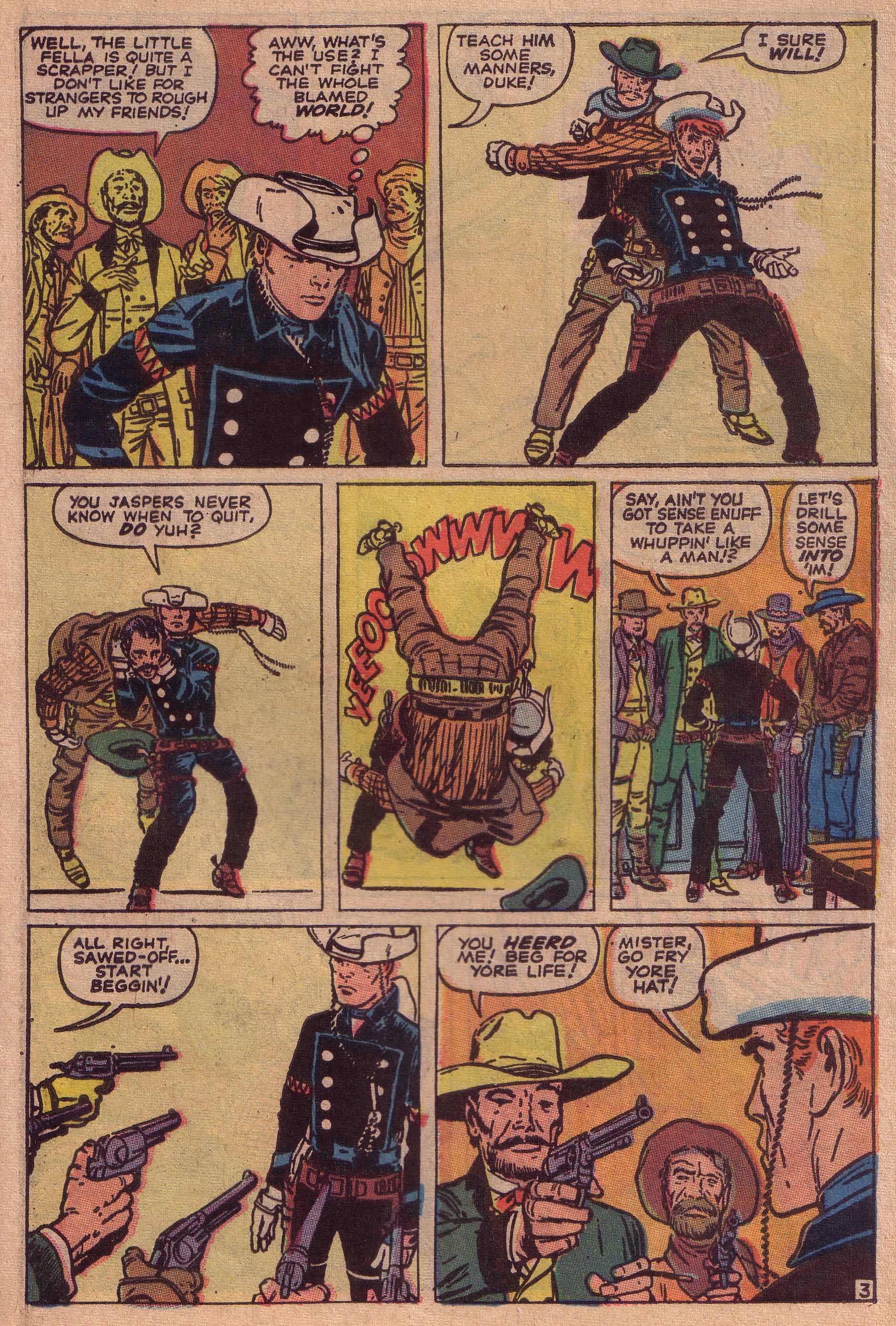

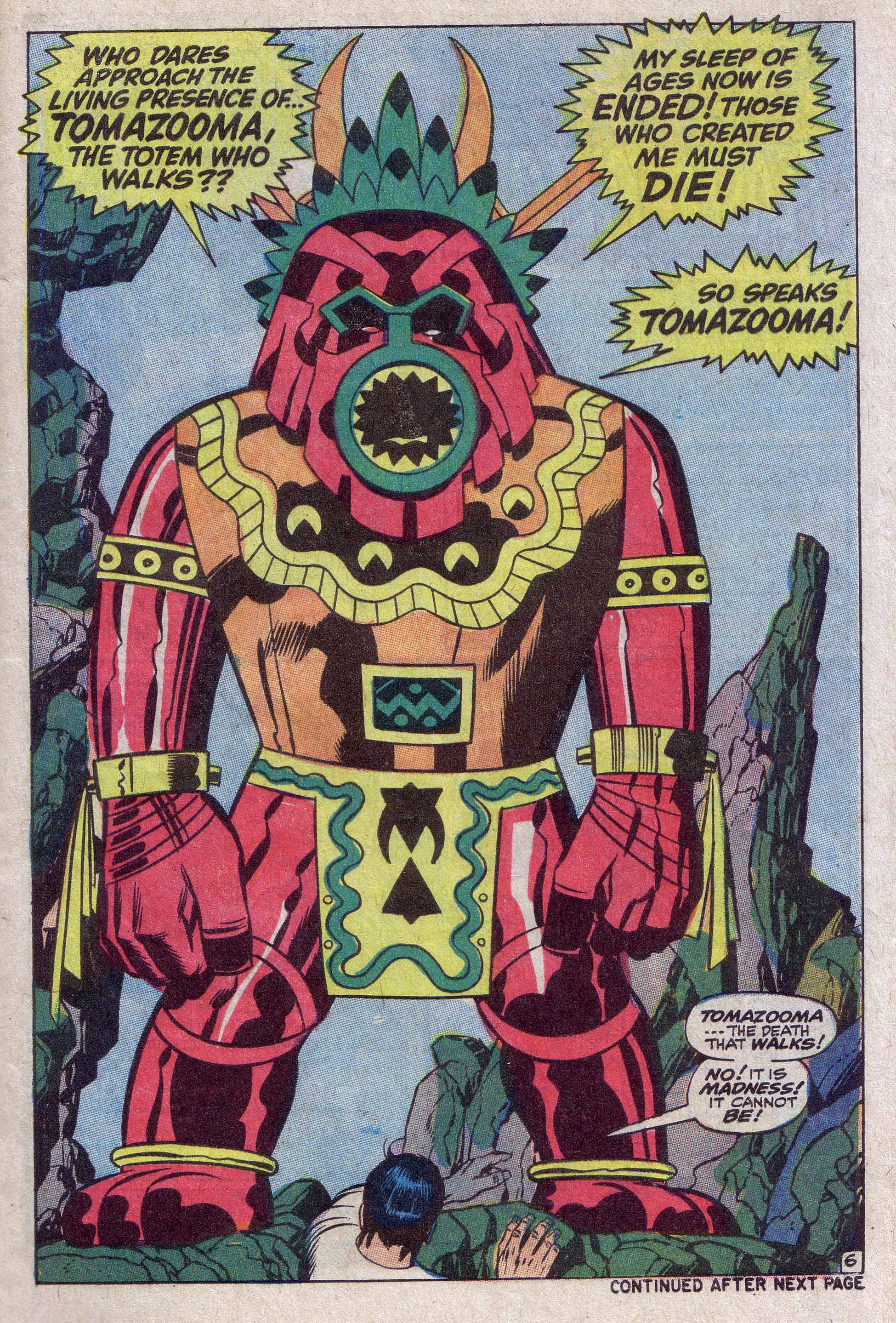

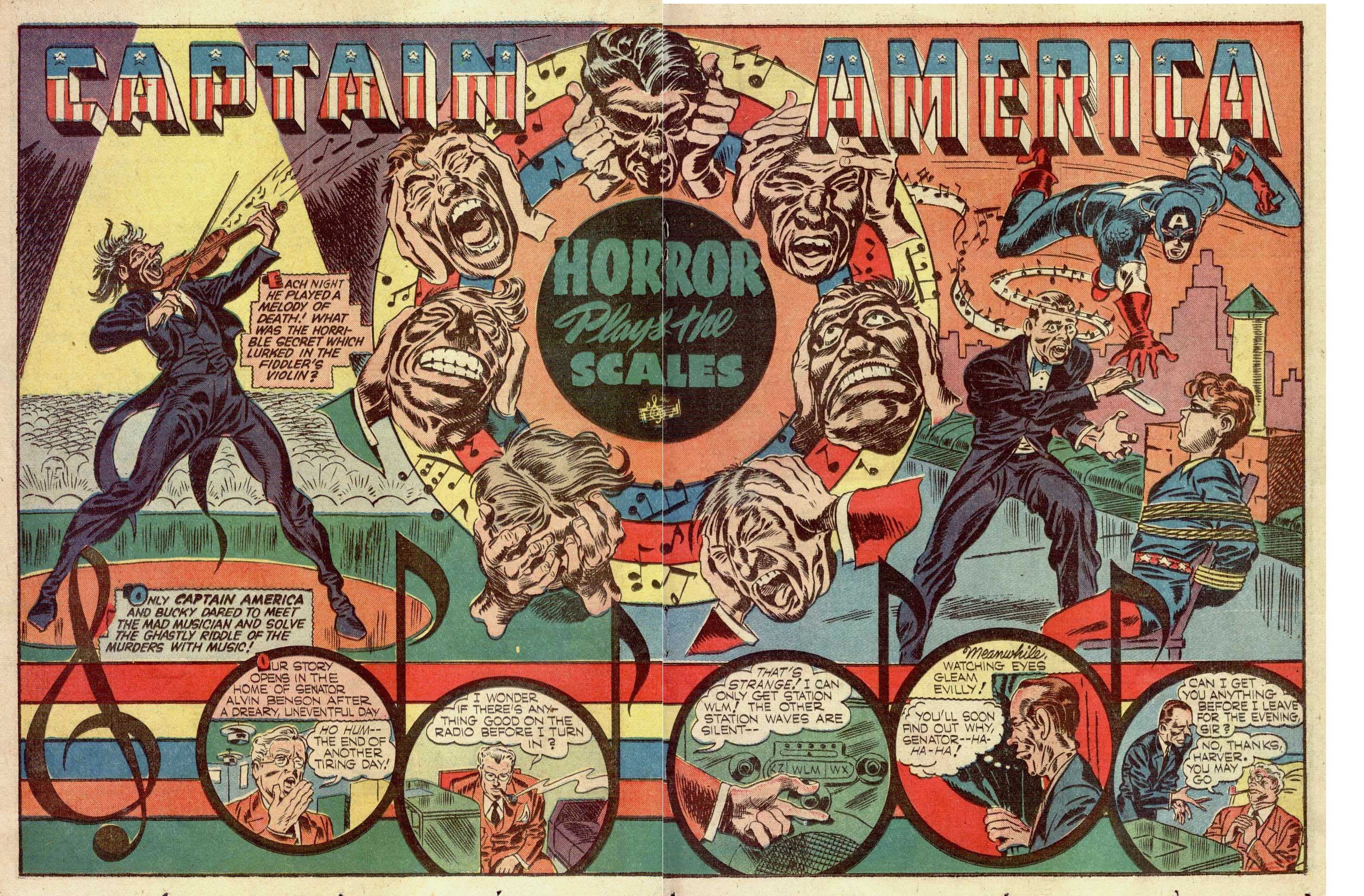

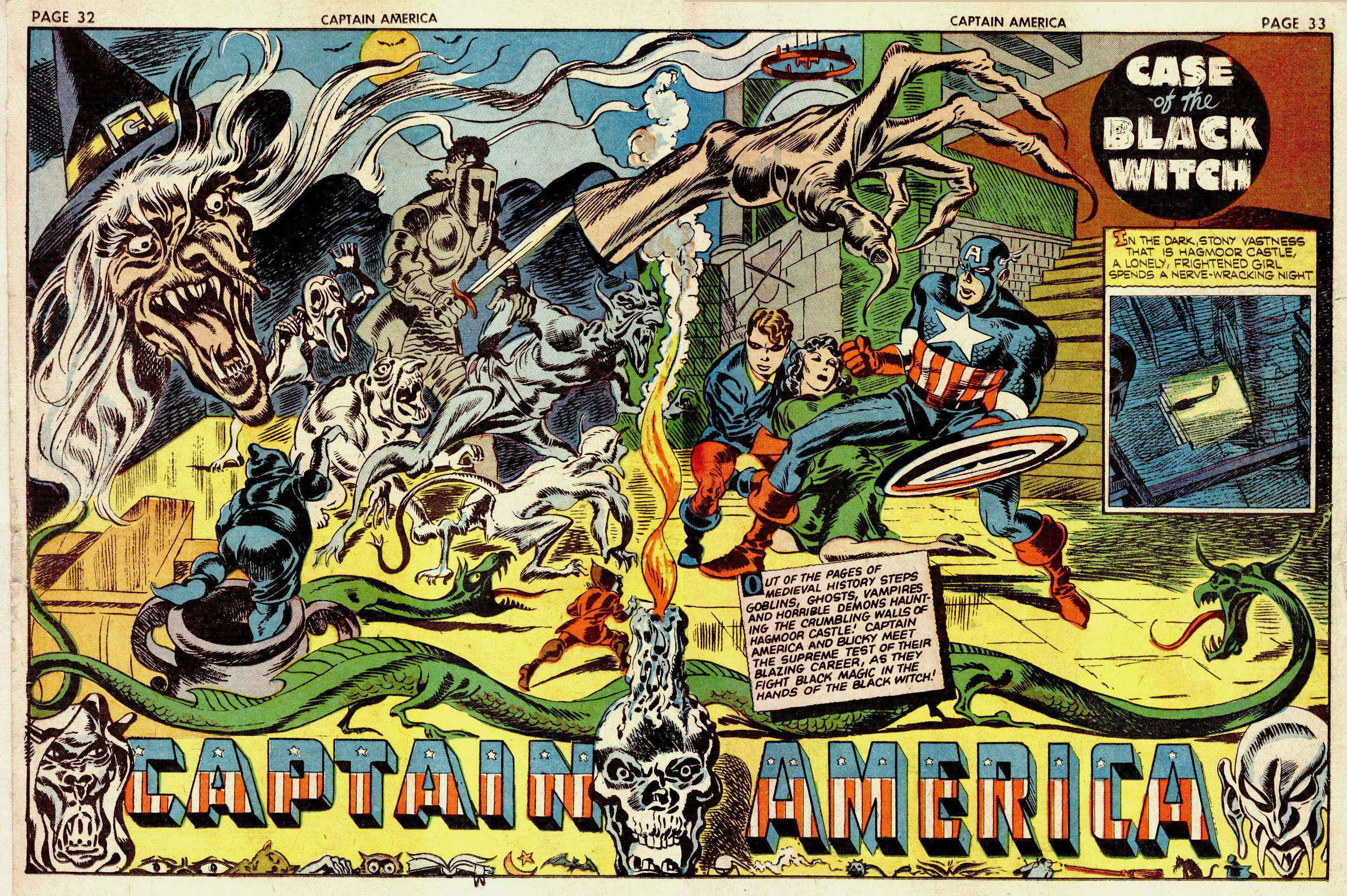

I grew up in the New York City borough of the Bronx during the late 1950’s. The area was relatively placid and featured a quaint array of candy stores and soda fountain shops with racks of comic books. America was gradually emerging from the grip of Cold War paranoia, and much of the cultural zeitgeist was focused on film and literature featuring intergalactic alien invaders and various kinds of monsters ranging from huge Dinosaurs to Zombies, Ghouls and vampires. At Atlas Comics, which would eventually become Marvel, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko were churning out stories showcasing Comics Code friendly versions of such creatures, some of which the ten-year old mini-me would purchase in pursuit of amusement.

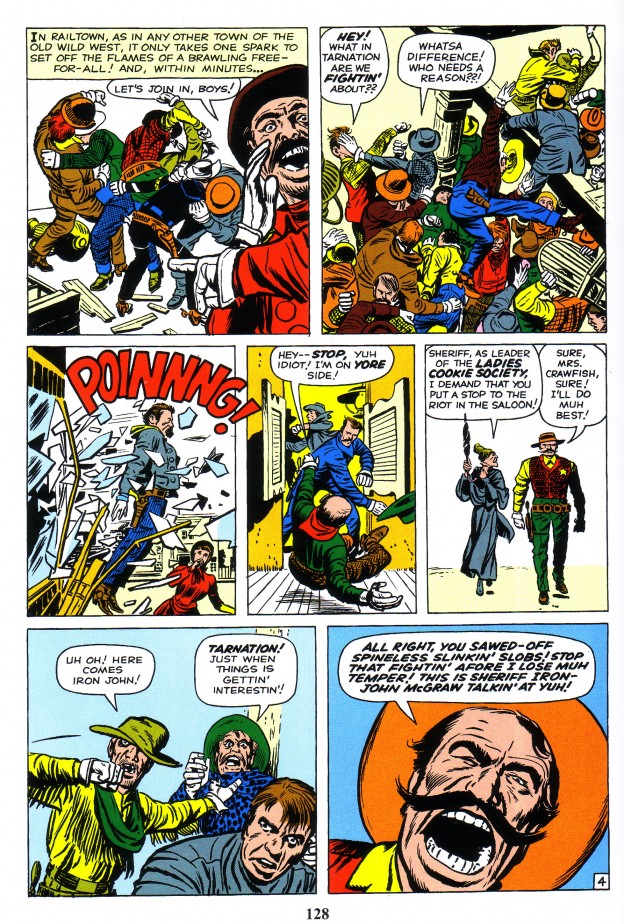

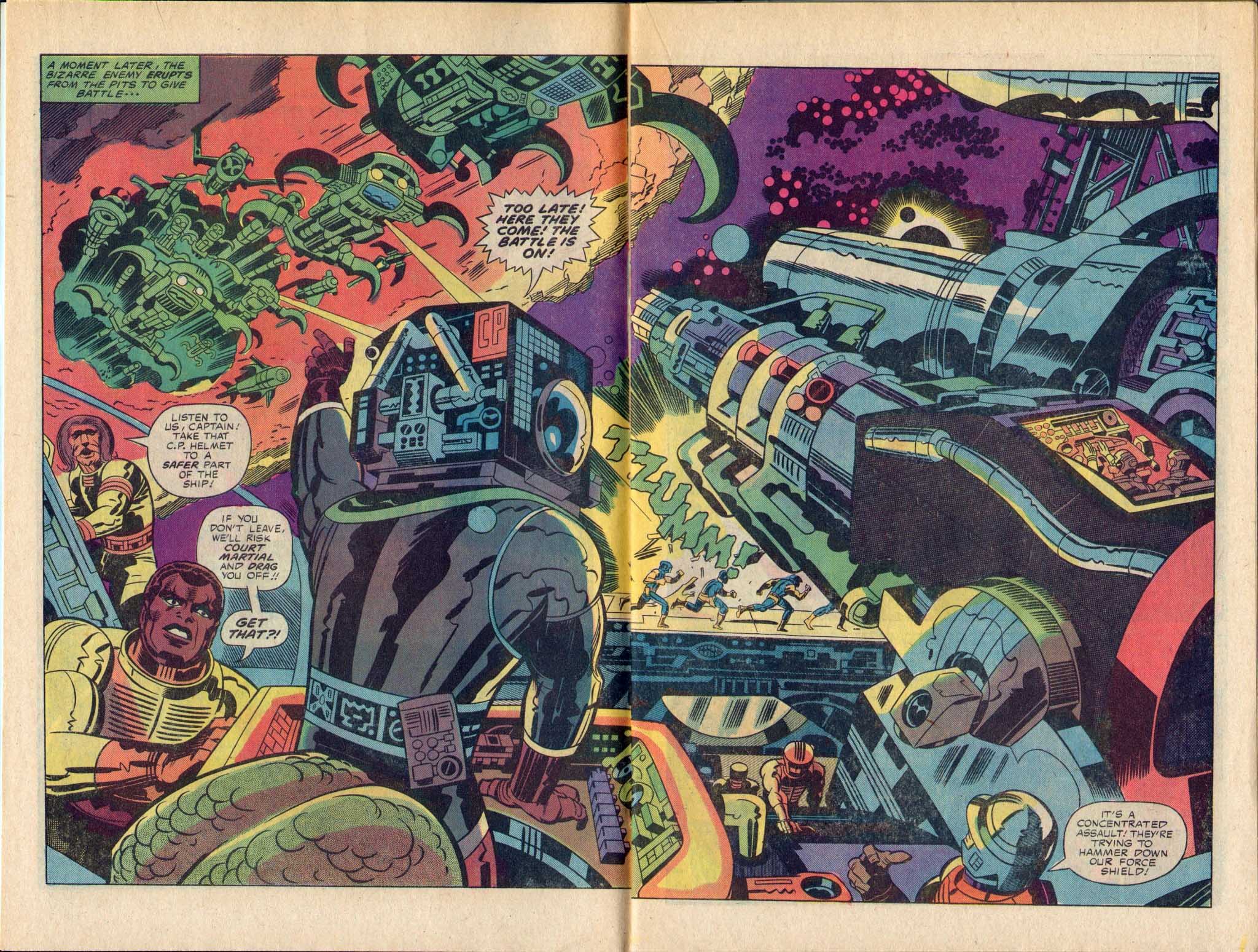

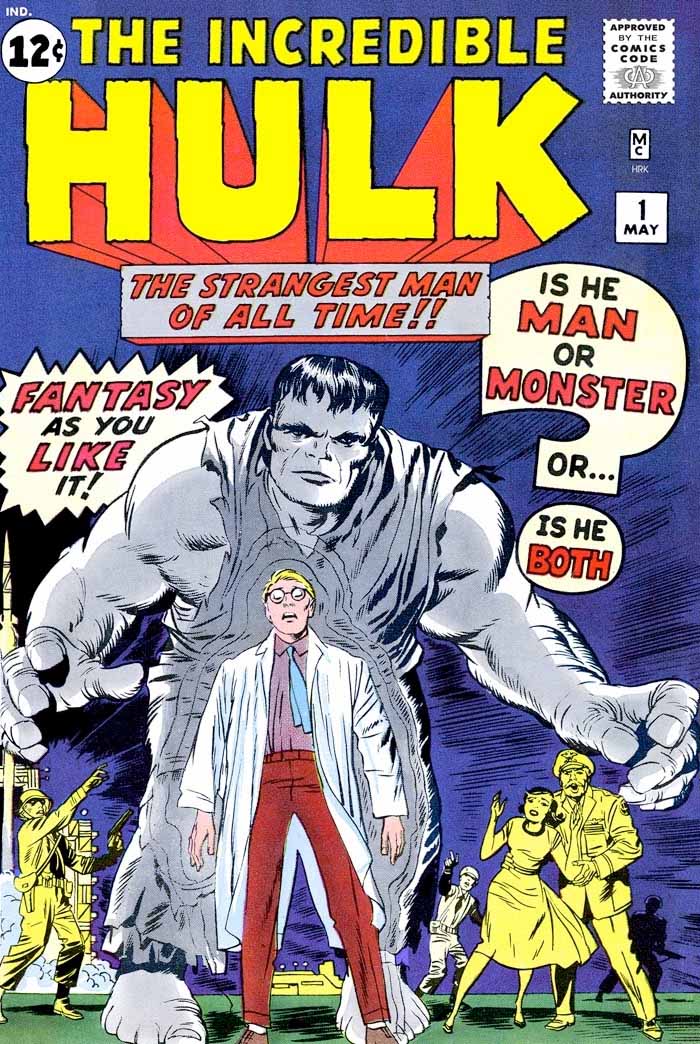

One day, after guzzling an “Egg Cream” at the soda fountain counter, I began perusing the comic book racks. My attention was grabbed by a heavy three dimensional block lettered title reading, The Incredible Hulk. “What the hell was this?” I wondered. Taking the book off the rack, I was captivated by the massive Frankenstein-like creature on the cover, as well as its profusion of word balloons. I was irresistibly compelled to take this comic home. Reading it, I was struck by the drama of the story, which as a developing artist myself, I immediately realized was created by the artist’s pacing. Having read several of this company’s other titles, I was becoming more familiar with Jack Kirby.

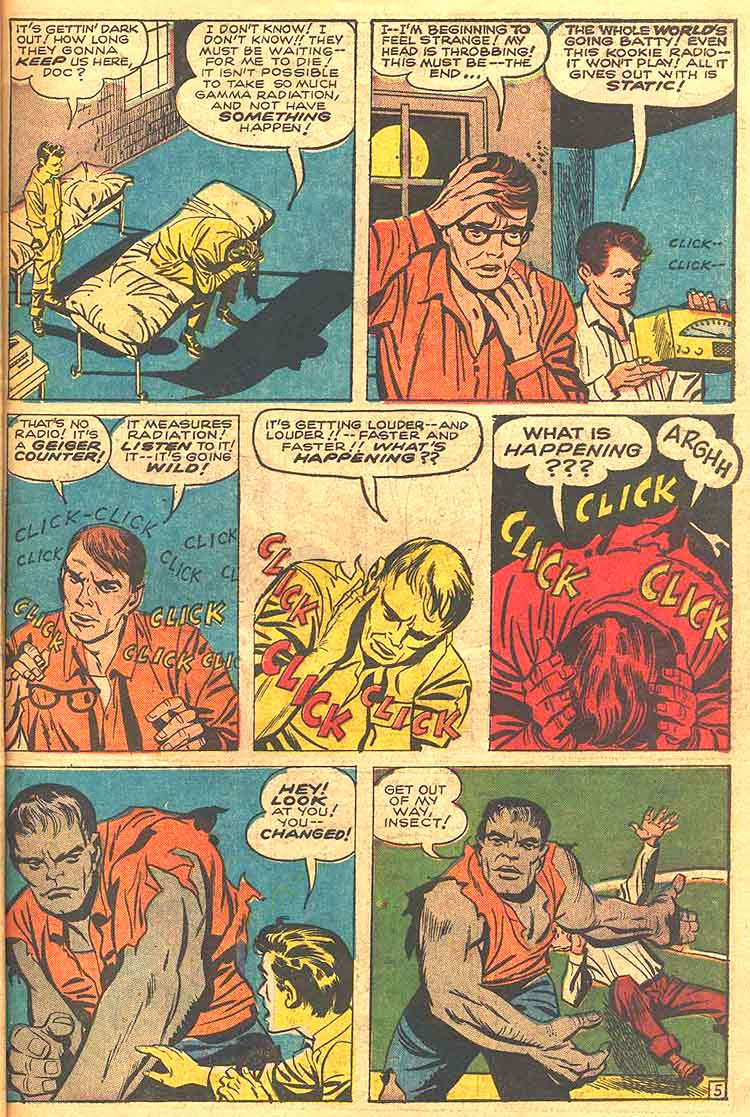

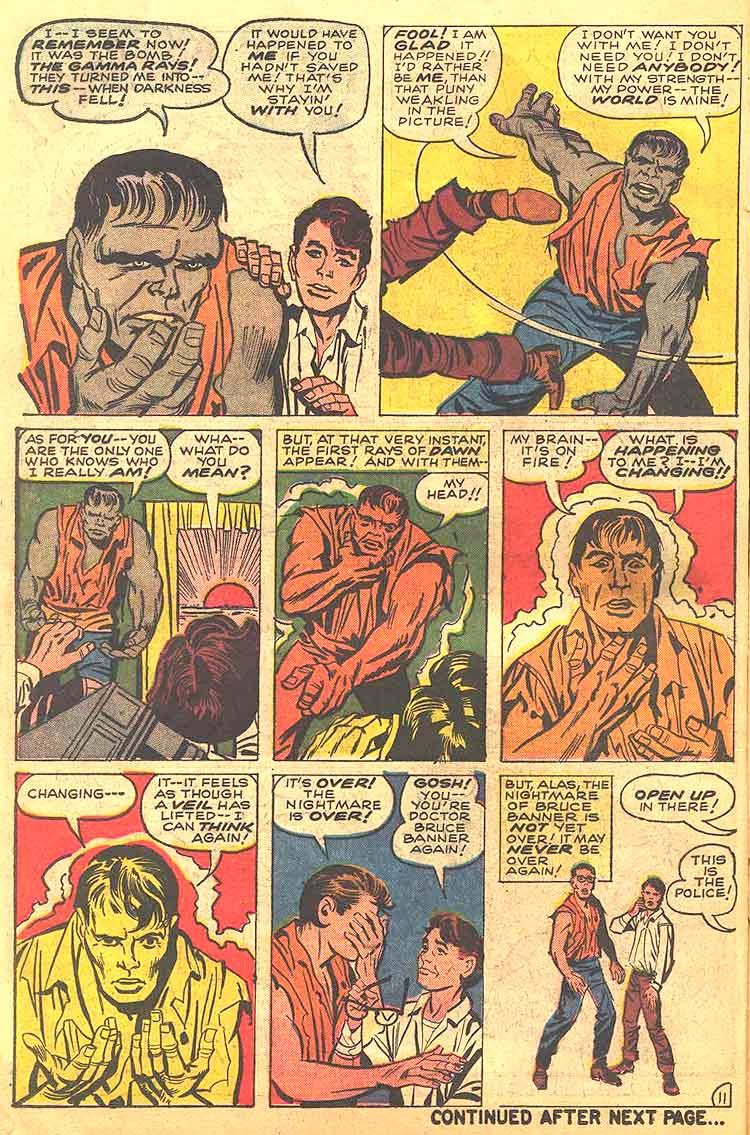

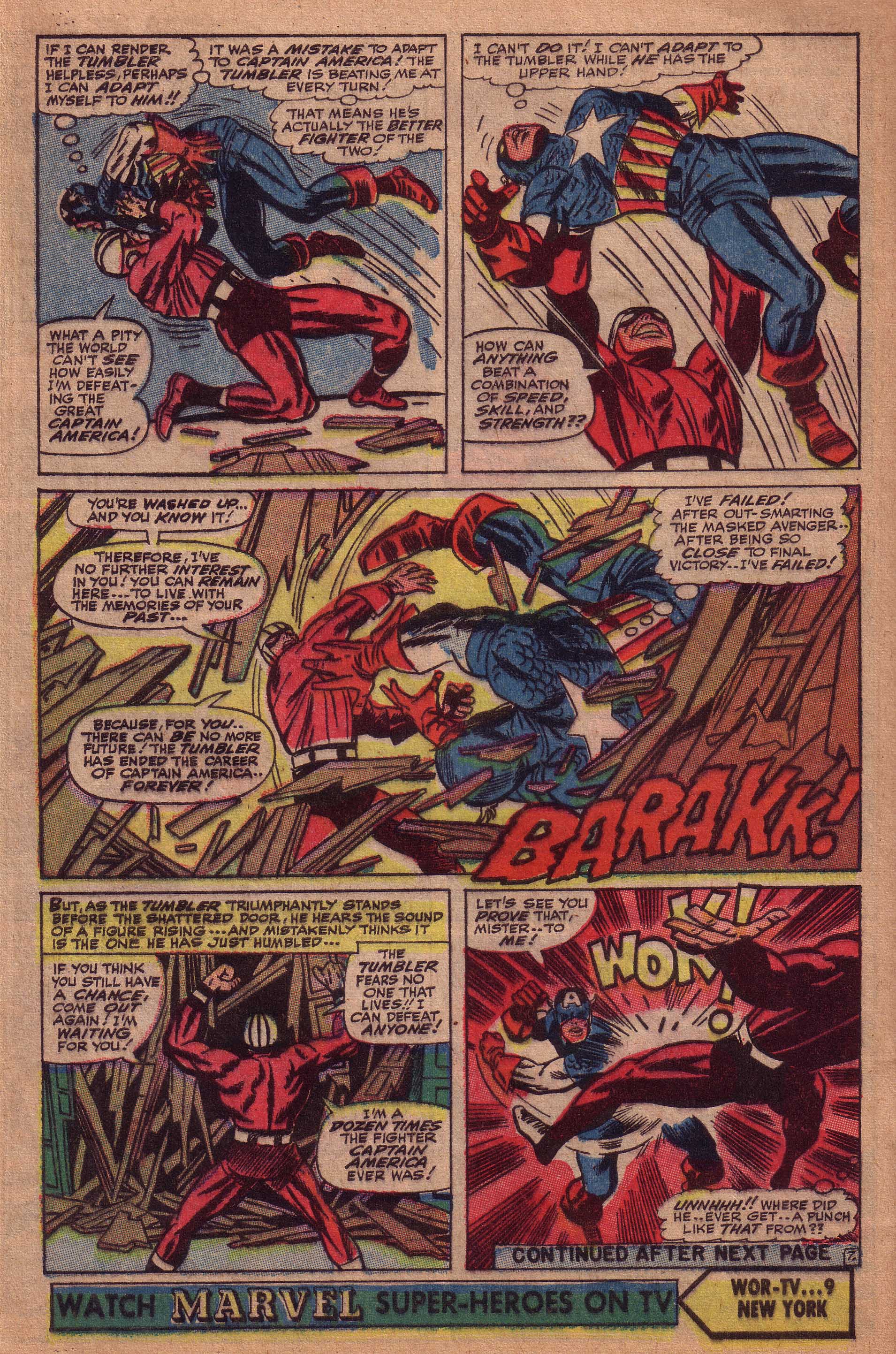

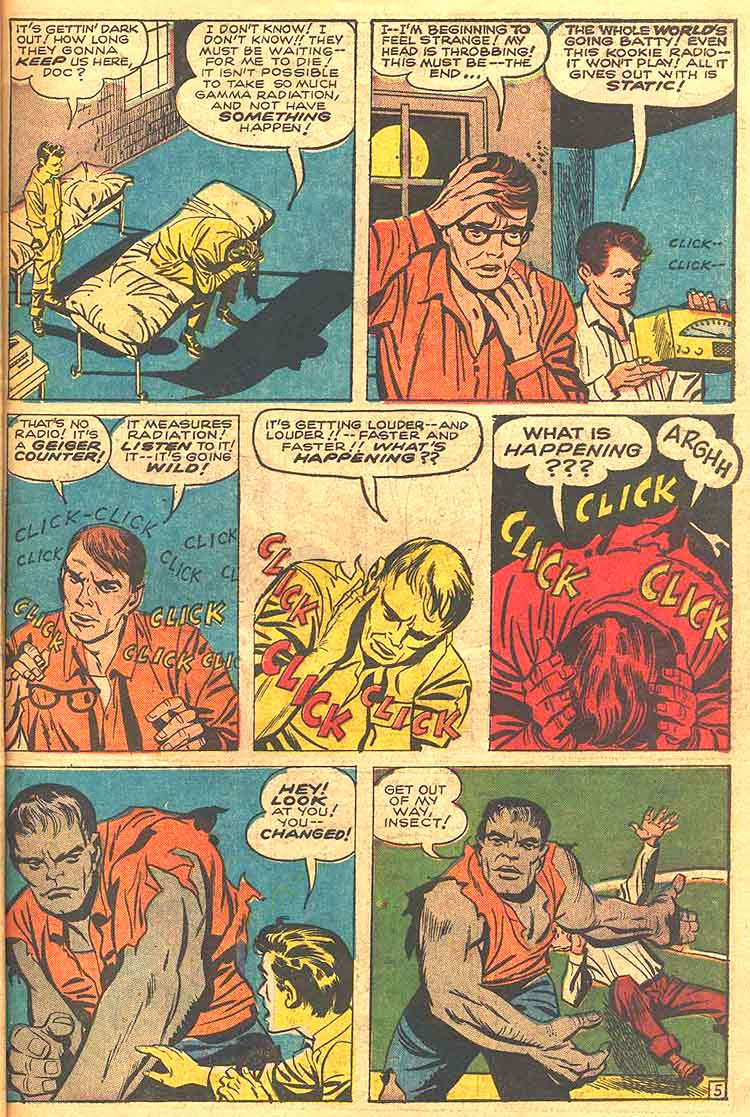

In the first issue of the Hulk, there were several dramatic scenes where the hapless Dr. Bruce Banner, as a result of his exposure to nuclear radiation was transformed by moonlight into a menacing monster possessing inhuman strength.

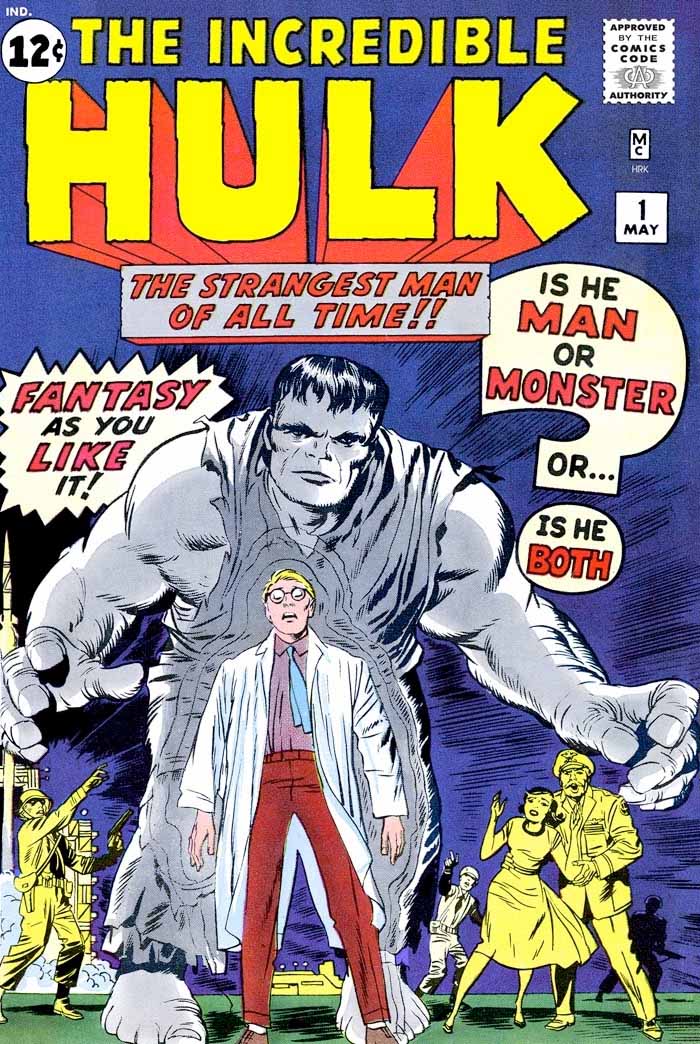

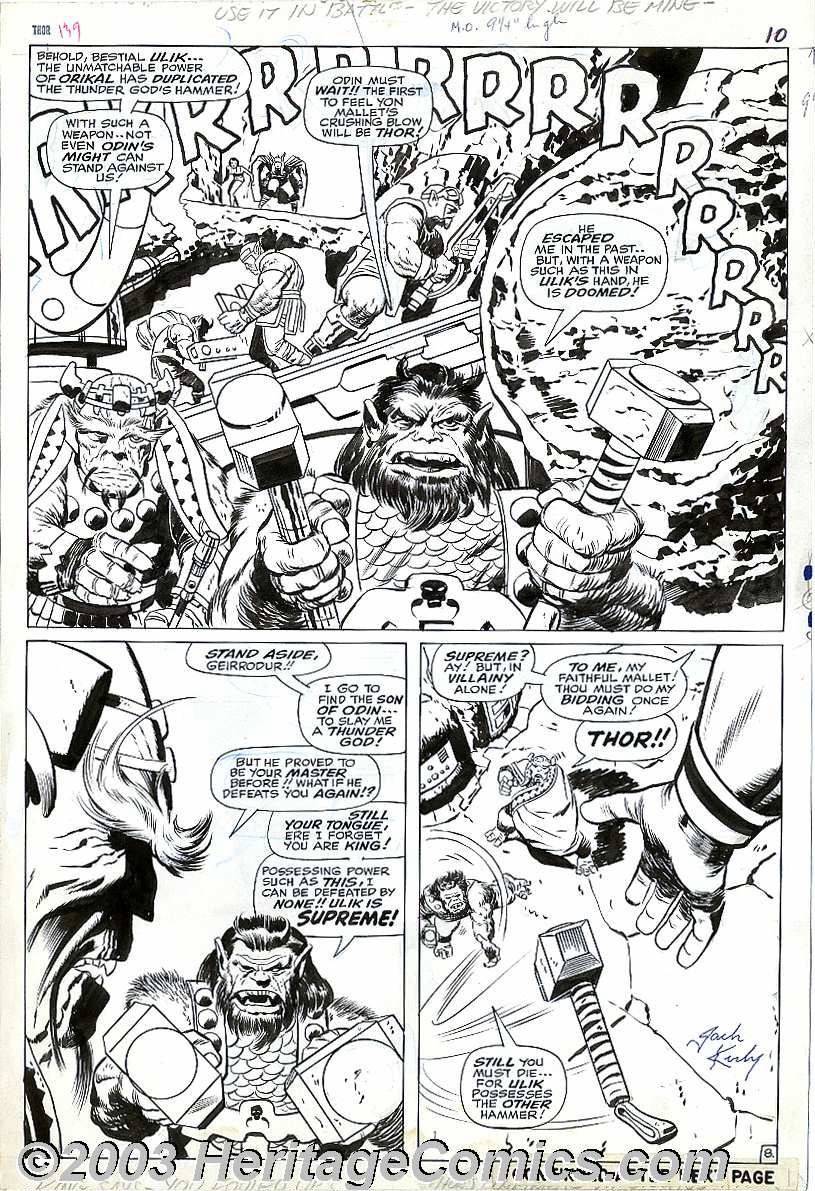

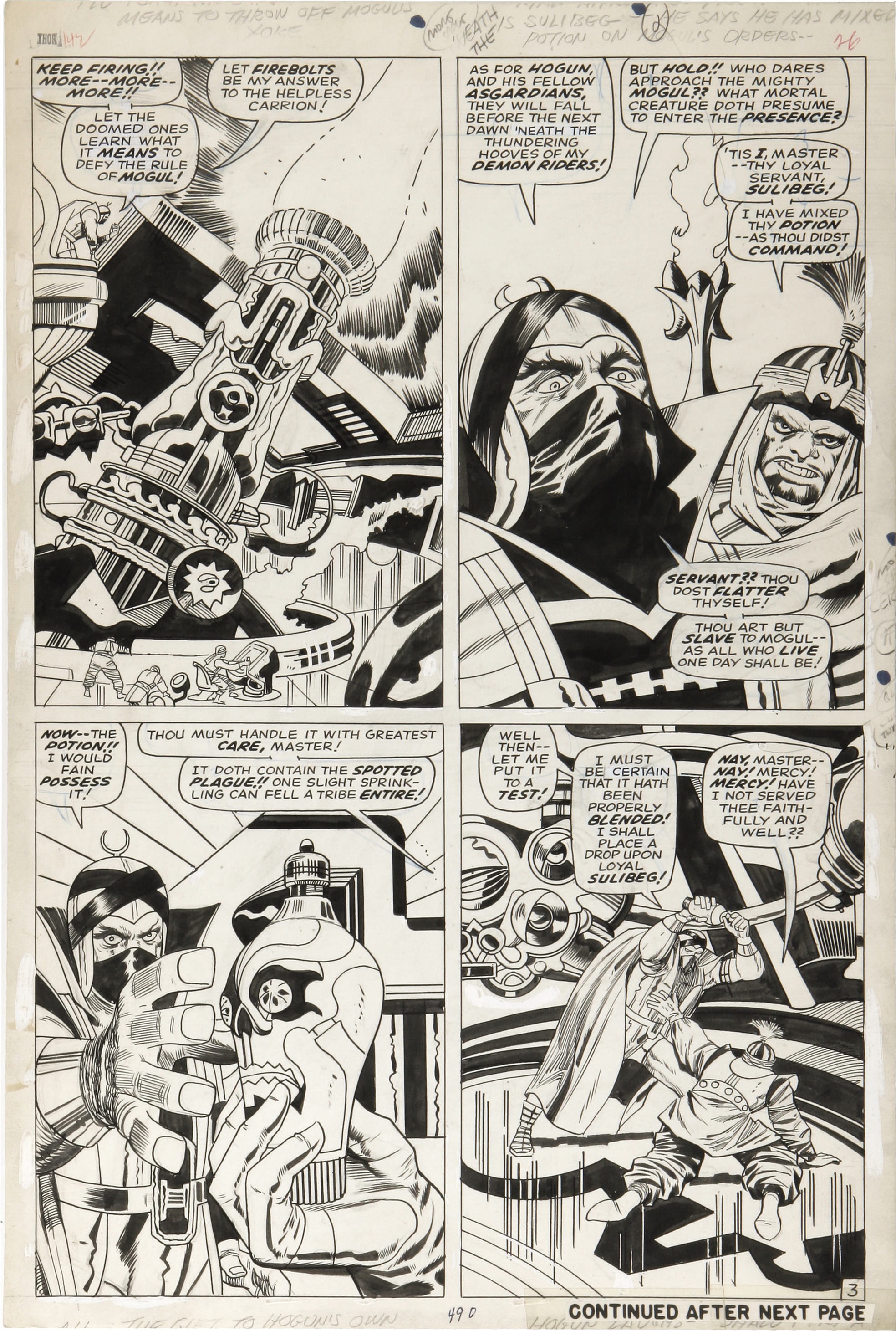

In the first such sequence on page 5 above, we see the disconsolate Banner sitting on a cot with head in hands. As he stands in panel two, we see the full moon juxtaposed behind his head. Next is the middle three-panel transition in the last of which we do not see Banner’s face, so that when he rises to his full height, we are taken aback by his grim gray visage as well as ominous drama of his posture. Kirby is an artist sometimes criticized for his non -strict adherence to the laws of anatomy, but here we see the King as usual using the body’s structure to its best advantage. Emphasizing the character’s menace, Kirby presents the monster’s massive shoulder and arm to the viewer, and then in a follow through motion in the next panel, shows it sweeping the helpless boy aside with that arm.

Transitions mark this particular comic, and Kirby exults in performing them. The book is fraught with the conventions of contemporary horror films, and upon reading it, I recognized that the moon through the window on page five reminded me then of the 1961 Hammer film Curse of the Werewolf, starring the young Oliver Reed, which was then one of my favorite of the genre.

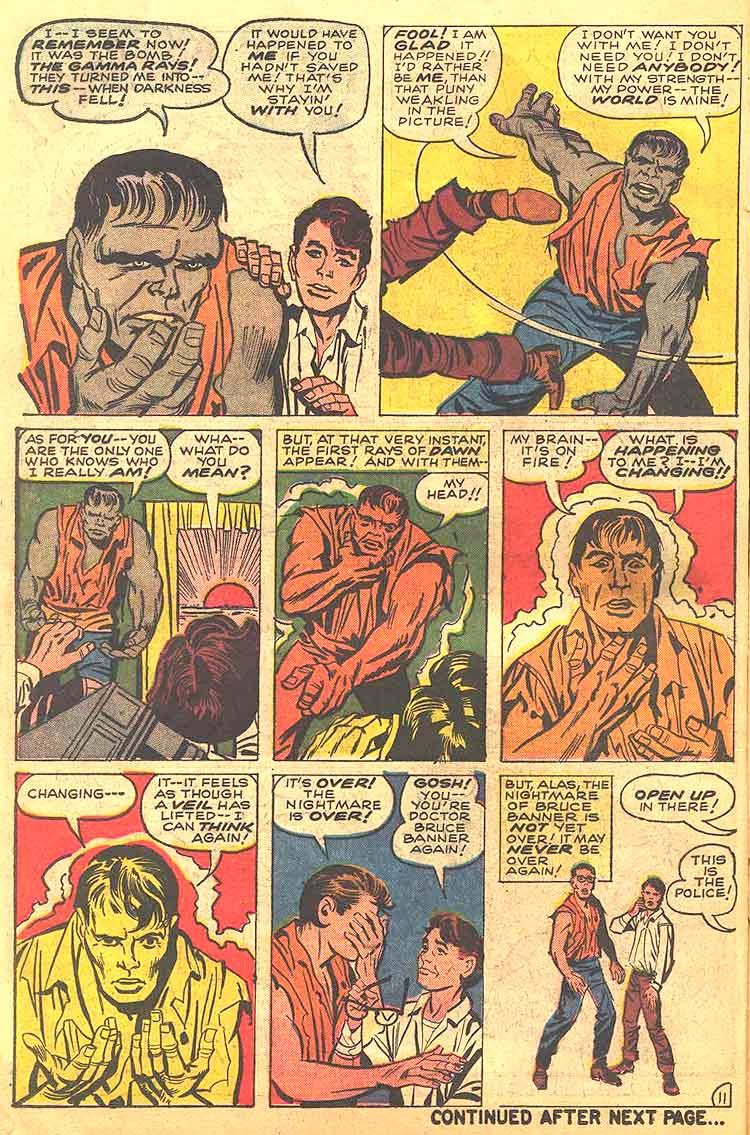

On page 11 above, as the Hulk threatens the teenage Rick Jones, the sun begins to rise and the boy is saved by the creature’s timely return to human form. Observe the change in the position of hands from the third to the sixth panel, as the Hulk first begins to gesture towards Jones who raises his own hands to fend off the creature. The Hulk then reaches up to clutch his own throat and finally in the sixth panel gazes down at his humanized fingers in relief that he is normal again.

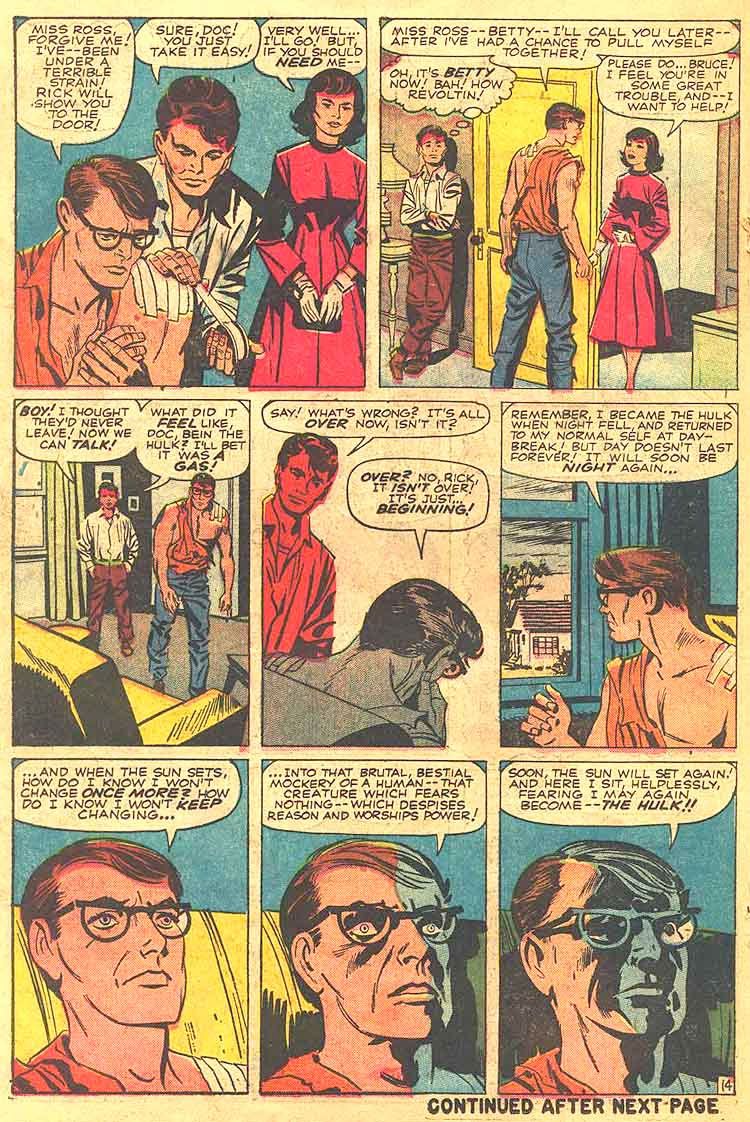

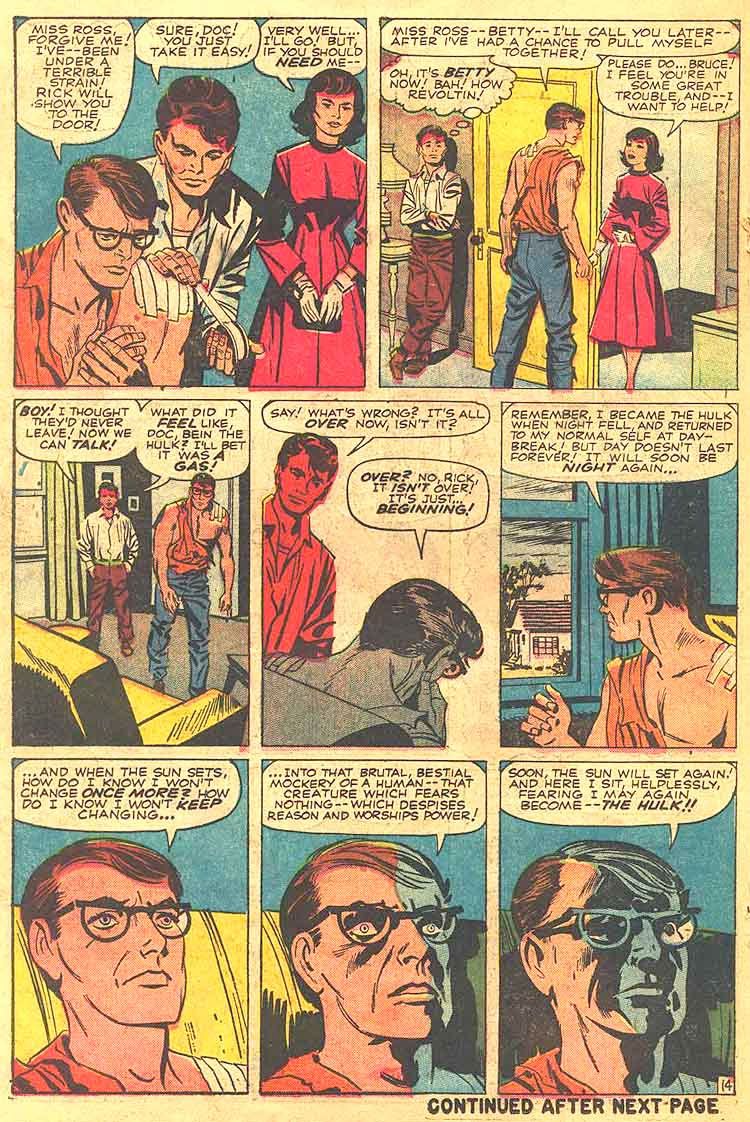

Later in the story, on page 14 we see Banner in the three panel lower tier, horrified by his pending transformation, and the drama of his terror is conveyed by the transition of the shadows on his face as afternoon turns to dusk

Finally, in one of the most dramatic sequences on page 18 below, Banner is driving and we see the transformation solely in a close cropping of his hands in the customary three panels, holding the steering wheel in the first, and then letting go of it. Kirby has always insisted that hands are are crucial tool for conveying emotion and he often uses a close cropped focus solely on them to elicit drama.

In the third panel, his hands, having released the wheel clench grotesquely and we see only the vehicle crashing in panel four, followed by the wonderfully sinister close-up image of the Hulk’s head and hands rising from the wreckage.

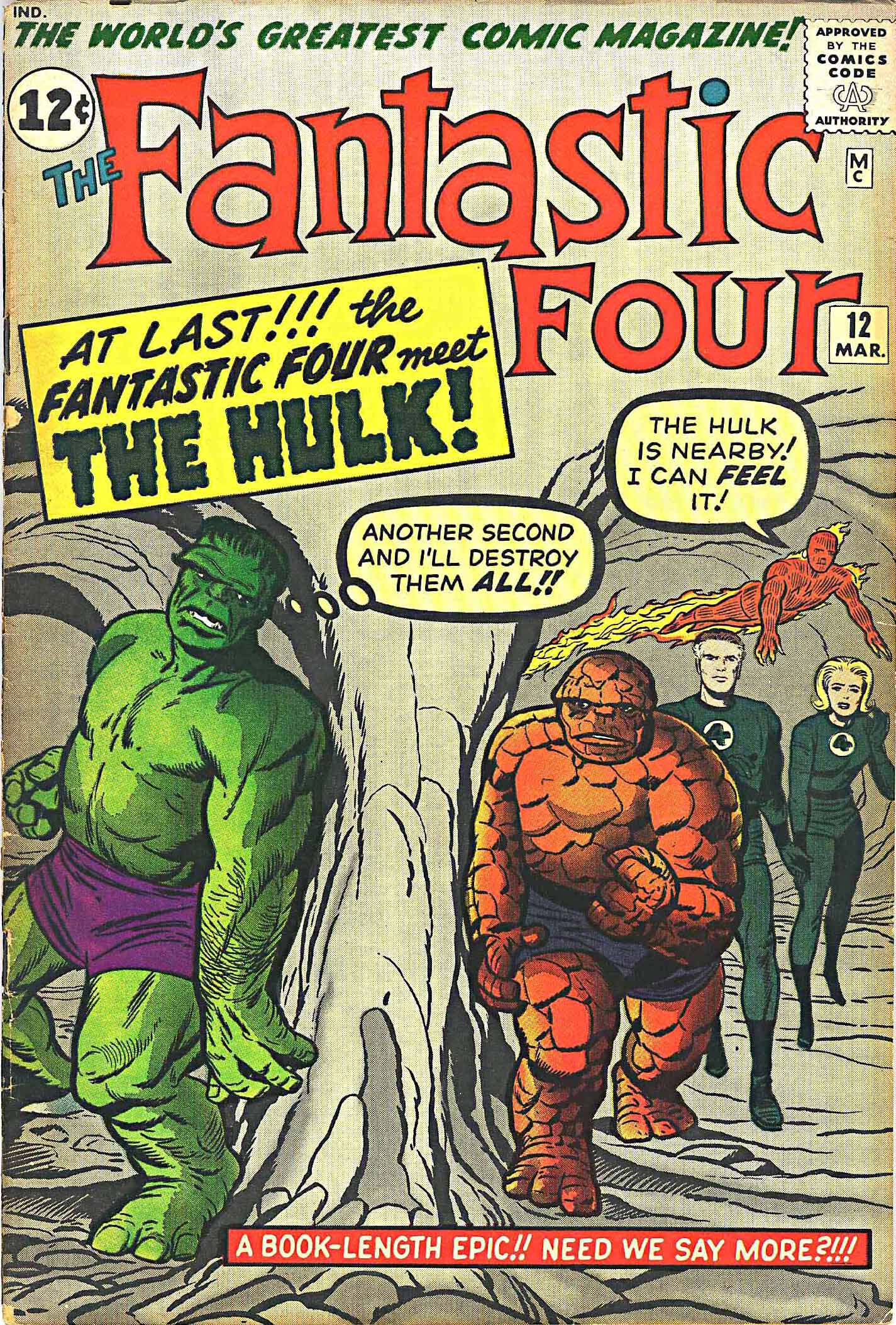

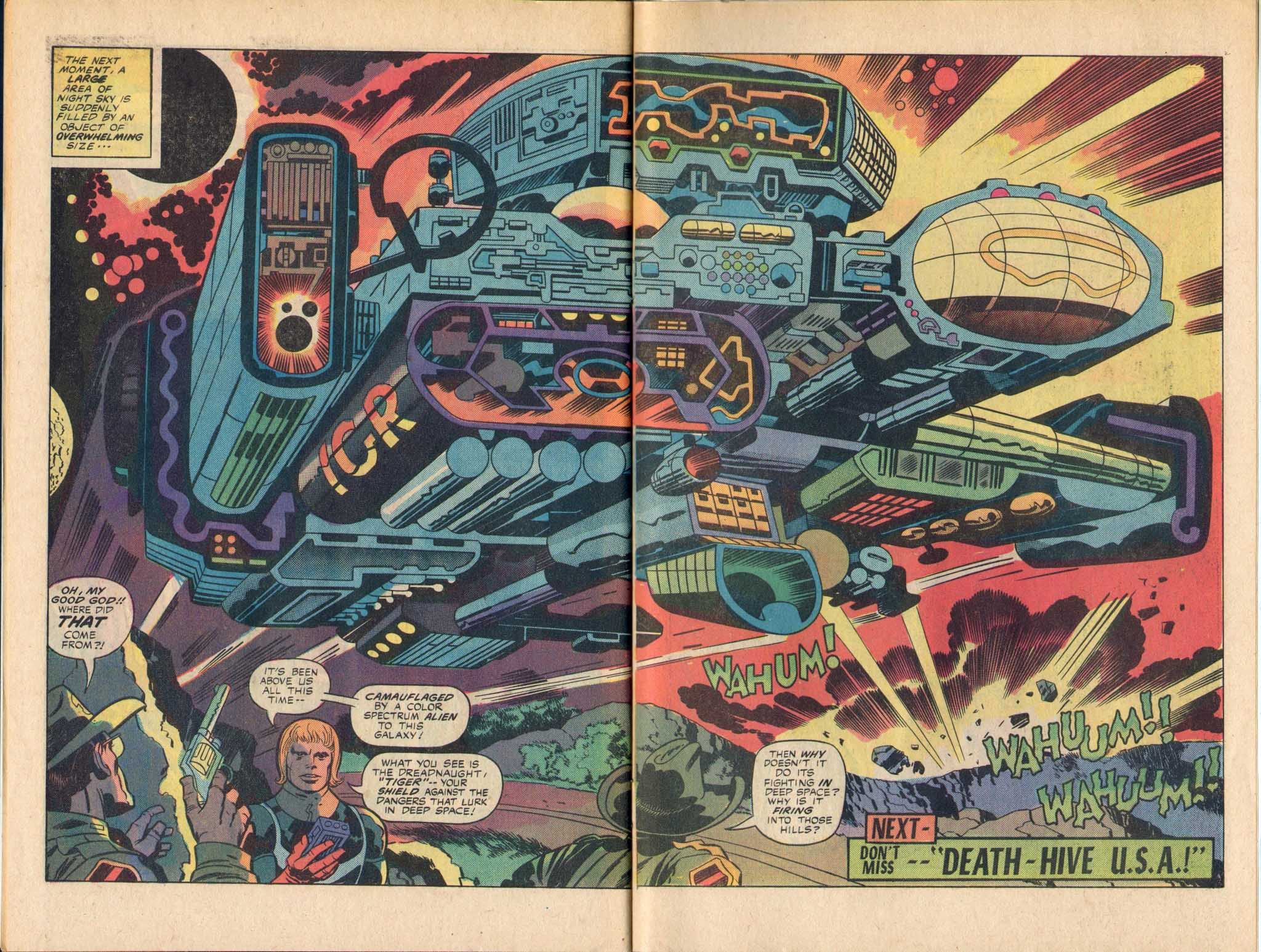

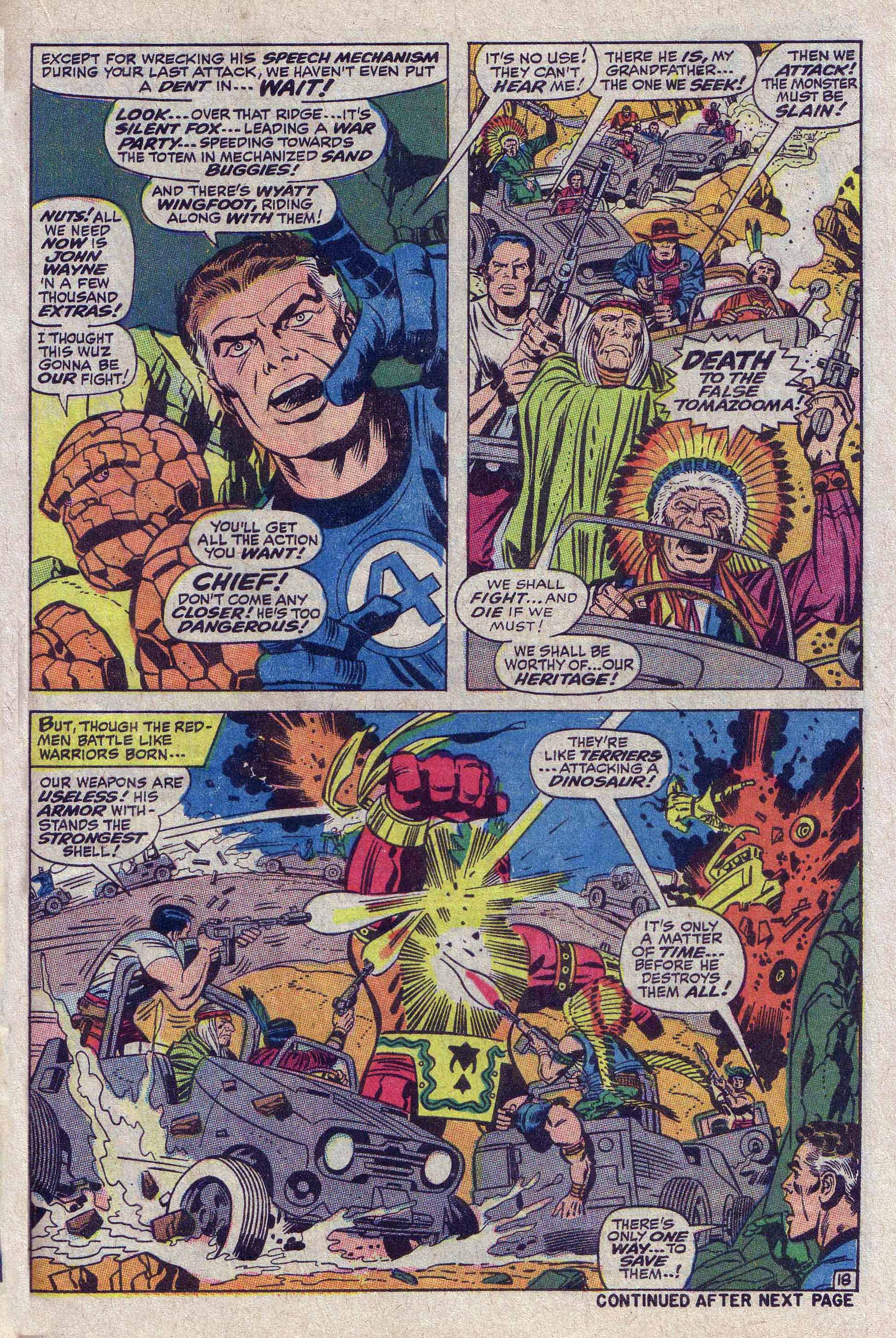

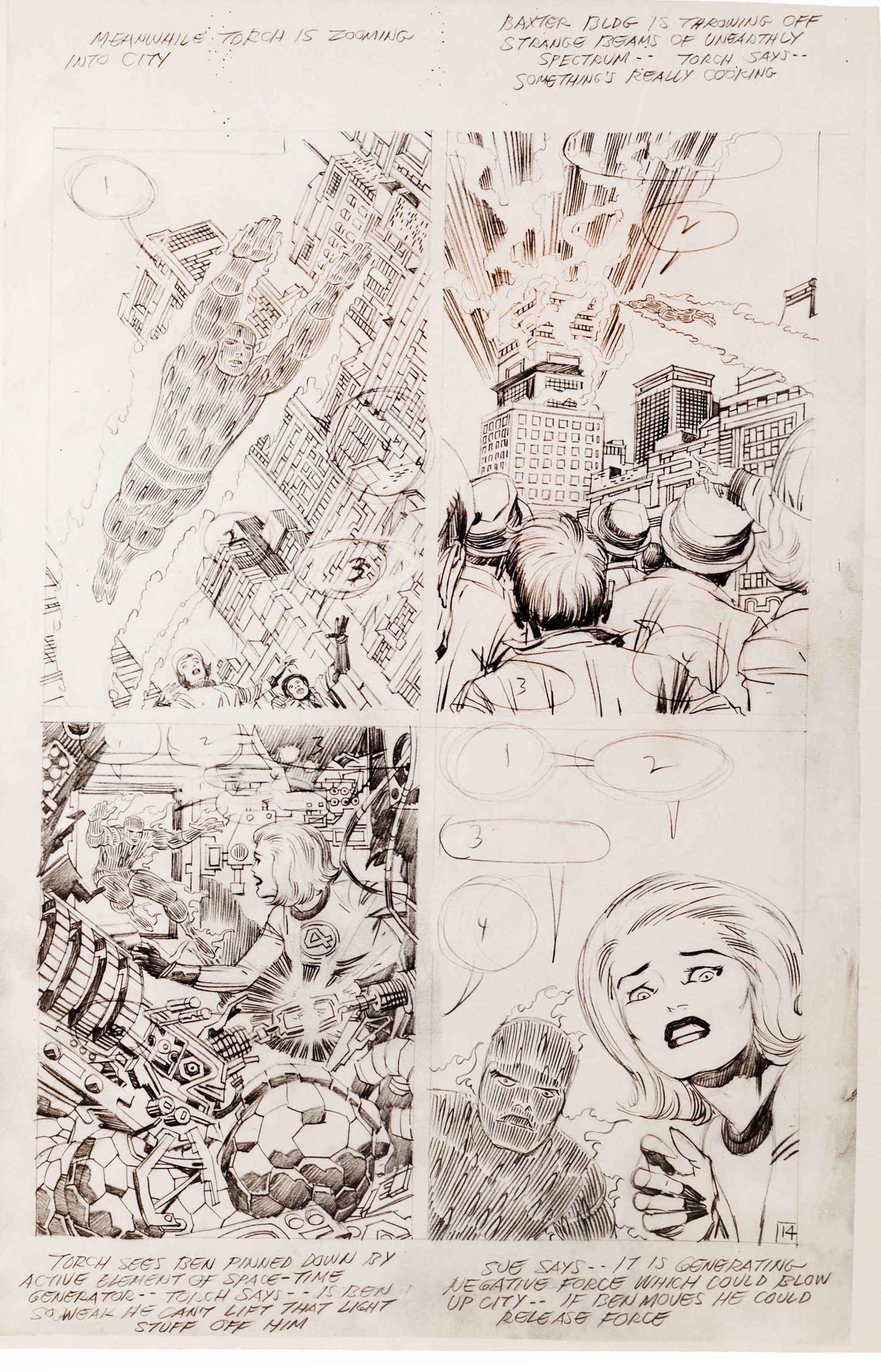

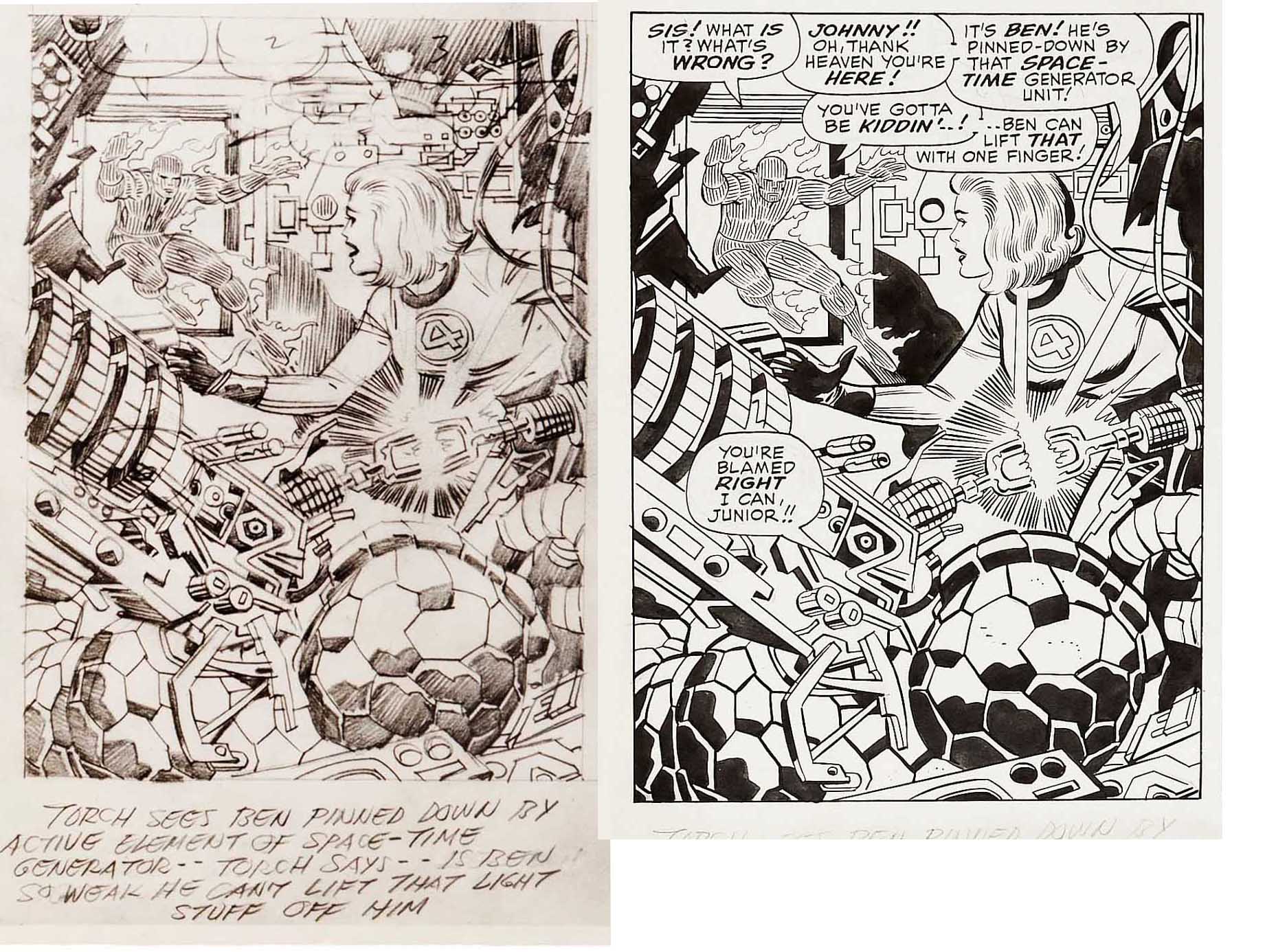

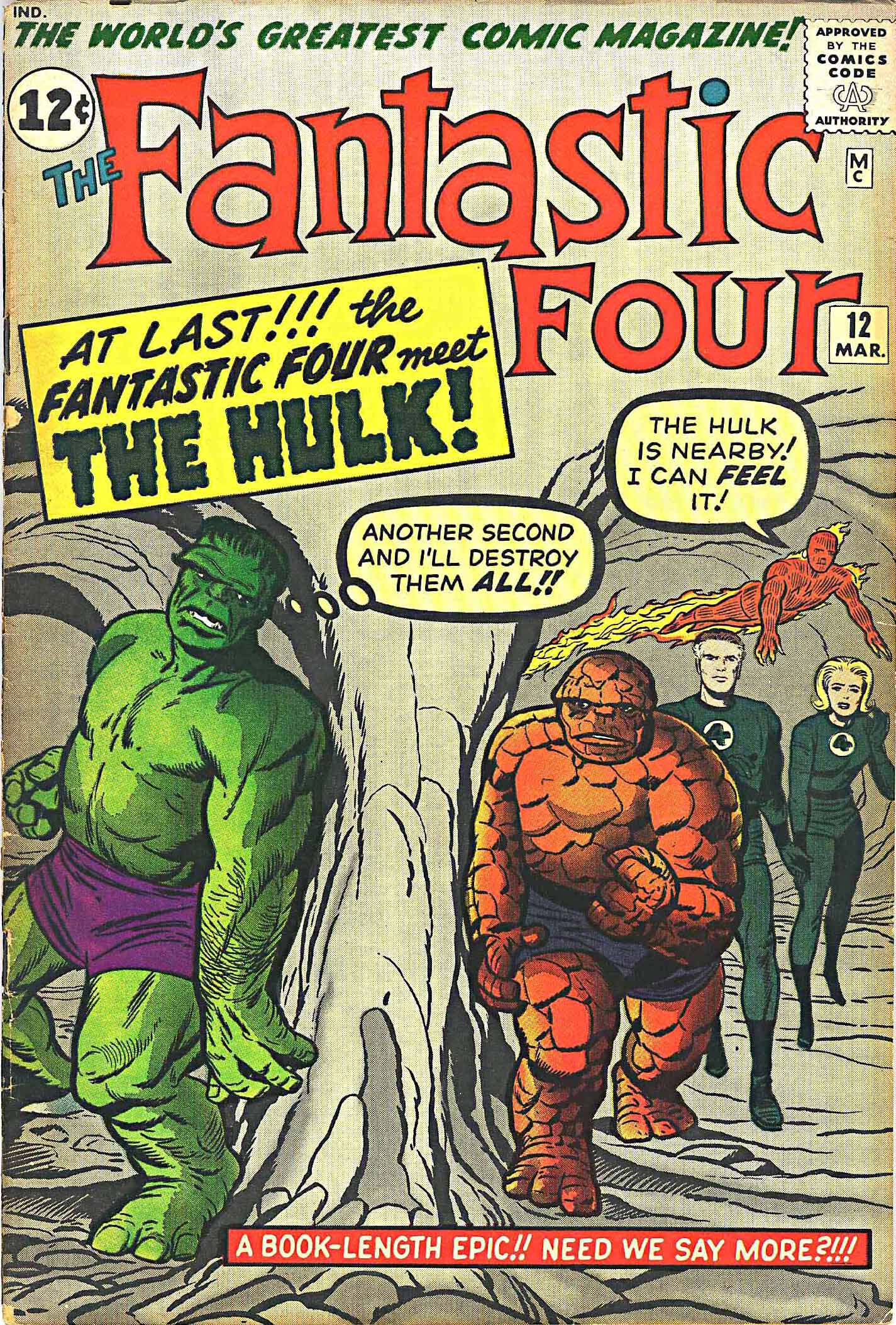

I followed the Hulk through issue #5 and was disappointed that Steve Ditko had taken over the artwork in issue #6. As much as I liked his work I did not feel his style fit the series. Then in that same month I chanced to notice a comic featuring the Hulk as a guest star. The Fantastic Four #12 was the first issue of that comic I’d ever seen. The cover was awesome, foreshadowing drama that unfortunately would not be realized inside the book. We see the Fantastic Four and the Hulk on either side of a foreboding cave formation. The Four are approaching the viewer as the Hulk ominously stands in wait for them. There was a scene like this in the comic, but the result of the confrontation was anti-climactic, not living up to the build-up that the story had created.

Still, I found the comic irresistible. This was the beginning of a youthful obsession. The Hulk was cancelled with the sixth issue, but it no longer mattered. I was hooked on the Worlds Greatest Comic Magazine and there was no going back. For the next eight years, I simply could not get enough of the Fantastic Four, and Jack Kirby had begun to leave a mark on my psyche that endures powerfully to this day.

Image 1-The Incredible Hulk cover- art-Jack Kirby, dialog-Stan Lee, restoration by Henry Kujawa

Images 2-5 Incredible Hulk #1- Jack Kirby, Paul Reinman, dialog by Stan Lee Scans courtesy of Rare Comics of Long island

Image 6-Fantastic Four #12-Jack Kirby, Dick Ayers- dialog by Stan Lee