August 28th 2017 will be Jack Kirby’s 100th birthday. Clearly, a good deal will be written about this occasion. I’d like to say something about what this event means to me, having grown up in a time period that had one foot in the old-world ways and one in the new. I was born in 1952, just seven years after the end of the great war, and that conflict’s mythology loomed large in my life. I lived in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. Abe Zimmerman, the Candy Store proprietor had Dachau numbers tattooed on his forearm. Needless to say, it would be a tough sell for someone to try to convince me that the Holocaust never happened.

To us neighborhood kids, the war represented good’s conquest over ultimate evil, and Jack Kirby’s characters embodied that epic. It felt like Jack Kirby was an American in the old-school sense. Few comic book creator’s heroes felt quite so righteous and principled. The United States is a nation whose credo was written on a plaque in 1903, inside the Statue of Liberty, which stands in New York harbor. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free. The wretched refuse of your teeming shore” is part of the text on the statue’s plaque. Kirby’s parents were just such “wretched refuse” as the poem was referring to. They were Austrian Jewish immigrants. and Kirby was raised on Essex Street in the bustling Lower East Side of Manhattan.

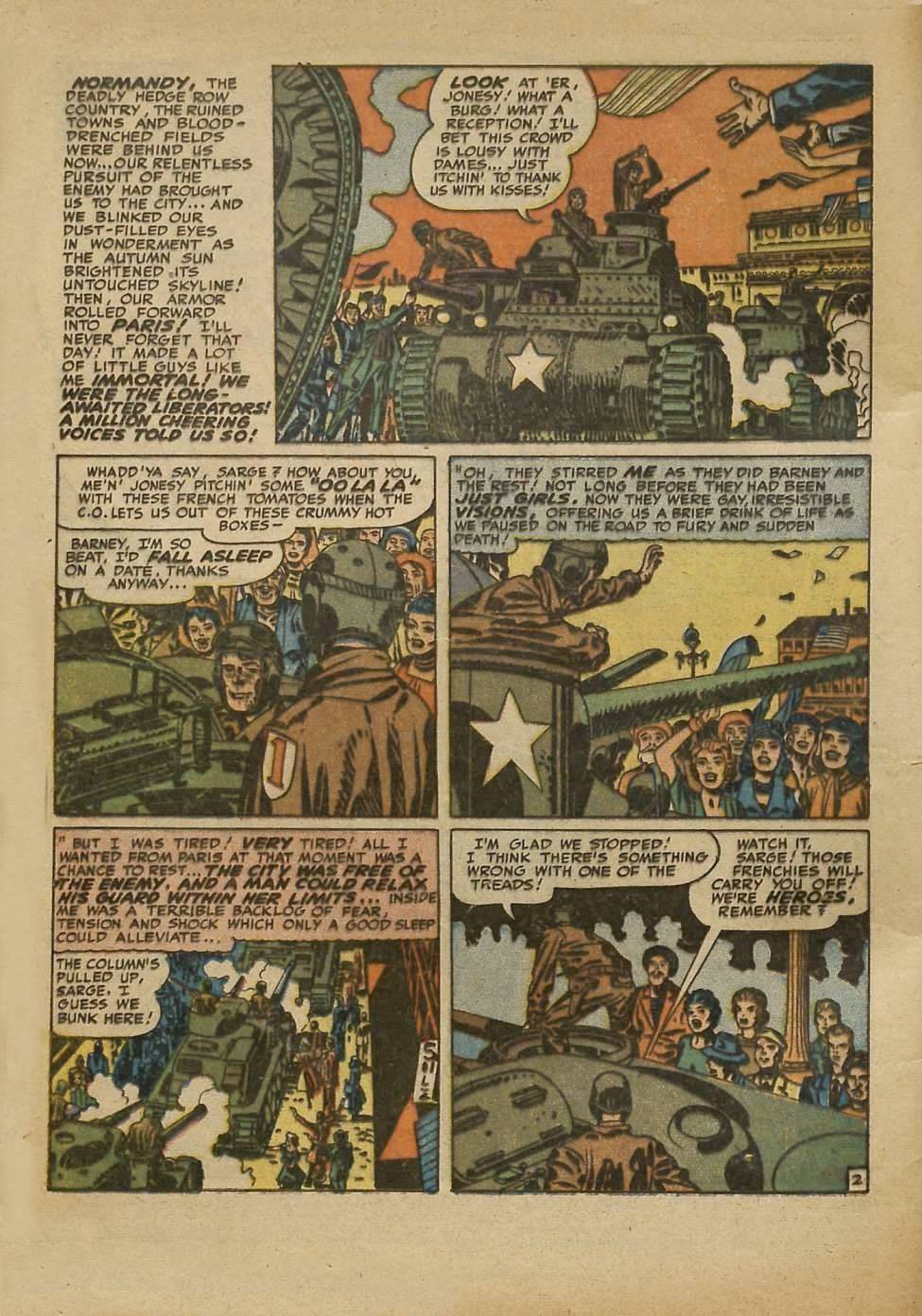

When the call came in the 1940’s for America to fight the fascism fomented by a former Austrian Corporal turned dictator, Kirby went to France under the command of General George S. Patton. Kirby came to Paris as a liberator. The page from Young Romance #10 above tells the story of a soldier that could easily have been semi-autobiographical. Kirby knew well those hedge rows, ruined towns and blood-drenched fields he wrote of.

When he returned to New York, he was a vastly different man, one who had seen the face of death countless times. He was no dull-witted killer who could shrug off such experiences. Every impression burned itself on his raw artistic sensibilities. His only defense against carnage was to transform it into art.

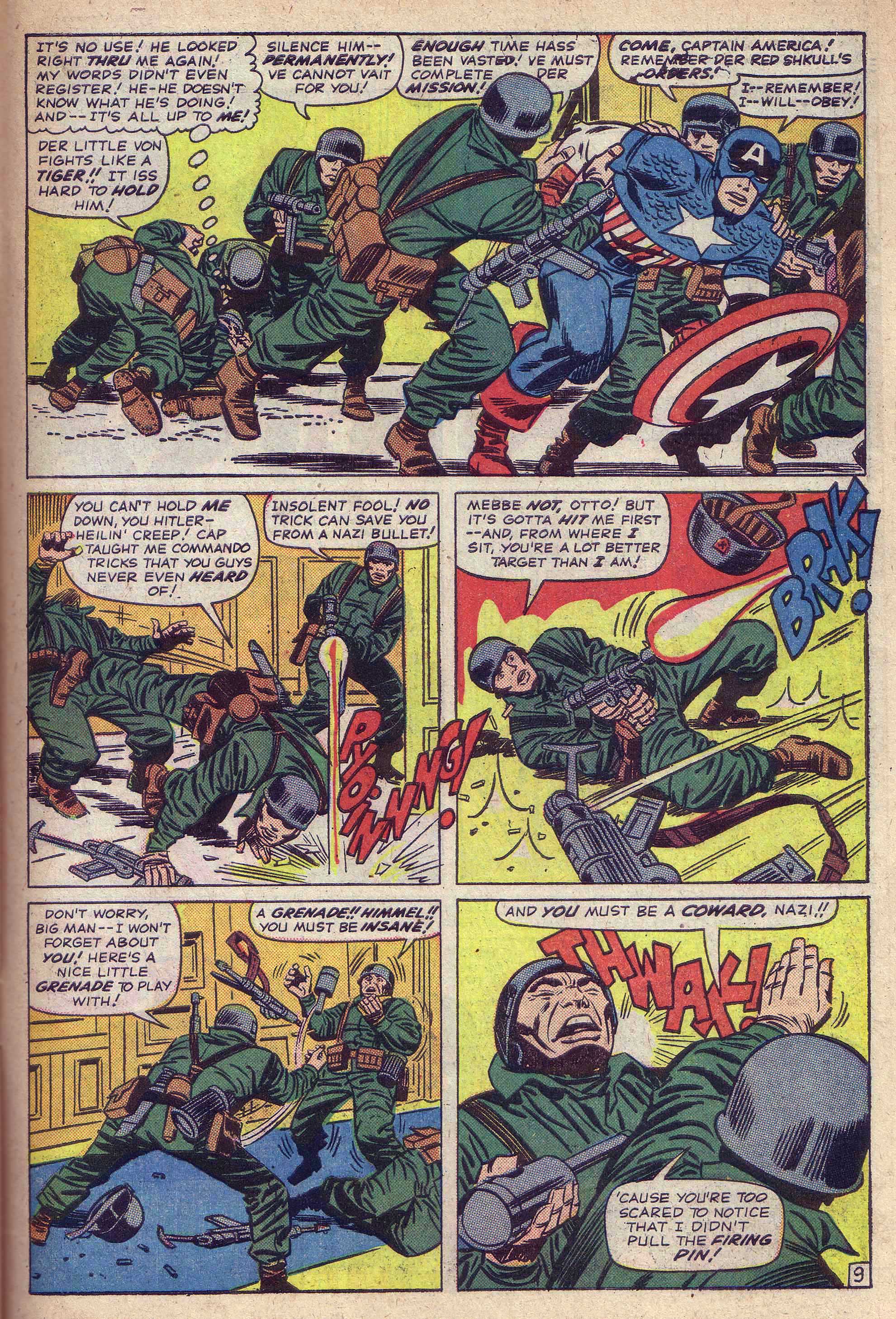

Kirby’s Captain America was the embodiment of his creator’s righteous rage at the forces of naked savagery that the artist had endured. Here on this page from Tales of Suspense #67, we see Cap, under the insidious spell of the Red Skull in the company of a squadron of Nazis. This panel has long been one of my favorite examples of compositional Kinetic energy. Every shape making up the structure of the surrounding Nazis is designed to give Captain America forward propulsion.

In panel two, Bucky explodes from a Nazi’s grip, while dodging a burst of machine gun fire. His rage is palpable as he snatches up a weapon and returns fire. There is no clever caption that suggests his bullets are less than lethal. There would be no point in trying to tone down the savagery of Kirby’s rage, channeled through Bucky. Next, he cleverly uses a grenade to outfox another Nazi and then subdue him in hand to hand combat.

There is something primal about the pages of this series from the mid-sixties, focusing on Captain America’s wartime adventures. Seldom again would Kirby return Cap to this period. Here, by bringing his golden age hero back to the time of his inception, Kirby appears to be exorcising some of his demons. The specter of Hitler’s Nazism was the very antithesis of the 20th century American dream. Teutonic racial supremacy vs. cultural inclusion and assimilation. Never mind that Steve Rogers was the spitting image of blonde, blue eyed Aryan godhood. He’d been born stunted and frail, but the spirit of American progressiveness had made him whole and infused with indomitable power over evil. This was the symbolic America of my youth. Without generosity of spirit and the dream of justice and equality, there could be no strength to overcome adversity.

Woe to any force that would falsely usurp that cloak of righteousness to mask their true intent. The anti-life equation was always lurking in the shadows. Kirby quickly saw through the travesty that was Vietnam. He had little patience for those that betrayed the ideal. In his Kamandi series, Kirby skewered Nixon’s flawed presidency in a hilarious satire of the Watergate scandal. His most powerful works, like the Fourth World series pitted the light of compassion and reason against the will to dominate and subjugate. This was the majesty of Kirby. His spirit was one that would enliven and justify the name that would be given to those he served with, “The Greatest Generation.”