It has been often stated that Jack Kirby briefly worked as an Inbetweener for the Max Fleischer animation studios prior to his comic book career. This suggests that Kirby was able to internalize the concept of sequential frames giving the illusion of motion and use it in his comic book art to make his work more dynamic. The standard for animation is between 12 and 15 frames per second. Obviously, this amount of panels would be excessive in a comic, but over the years, Kirby experimented quite a bit with the degree of continuity, often giving the reader a series of peak action poses in succession. Even in a comic book, where the panels are all visible, the brain has the ability to fill in the in between frames and give the motion a suggestion of uninterrupted flow.

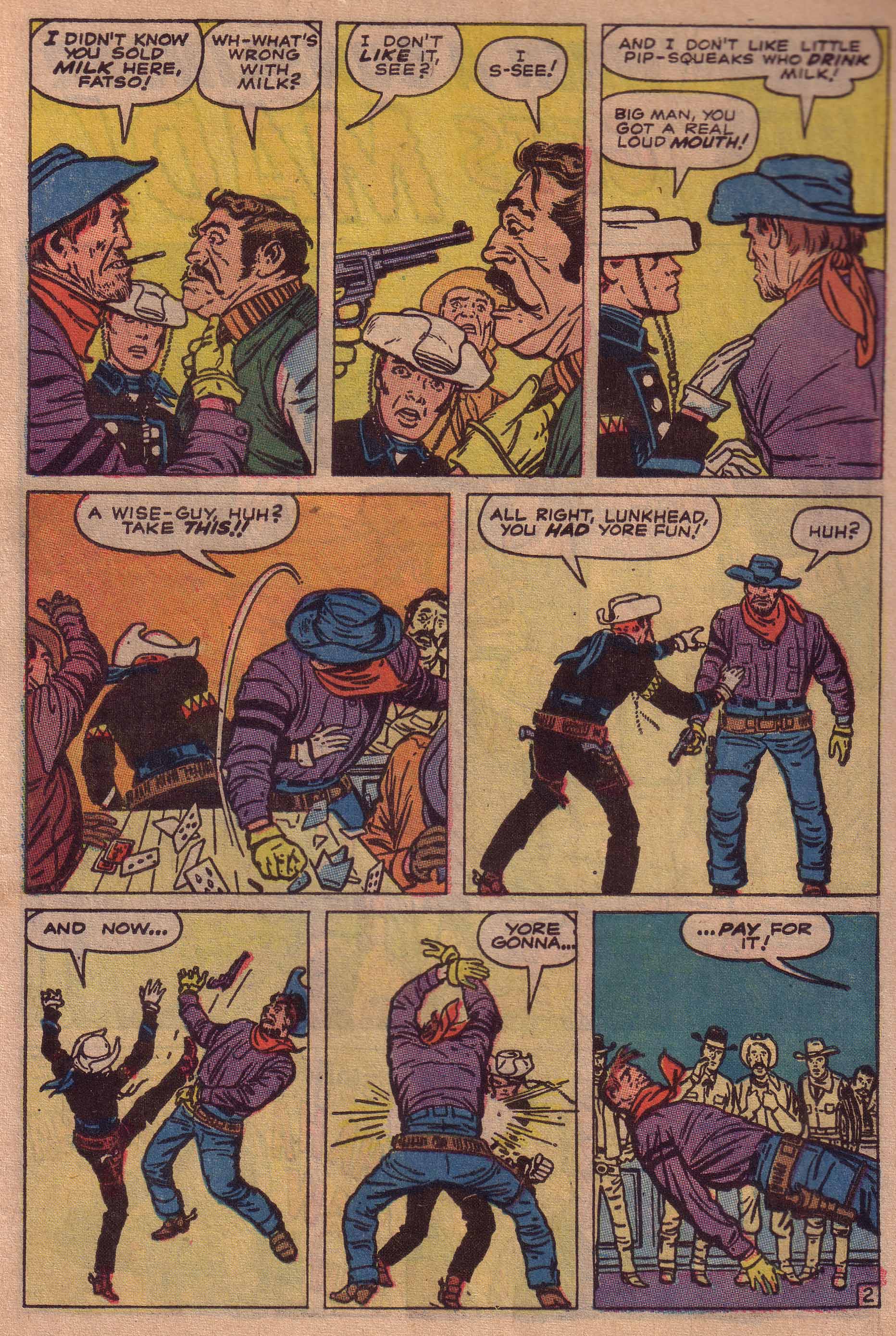

During the period that he was doing the Rawhide Kid, The King was more likely to give the visual reader a more unbroken sense of continuity to suggest a smooth flow of motion from one panel to the next. Notice the transitions in this series of panels above from Rawhide Kid #28. Kirby first gives us the profile of the gunman on the left and that of the bartender on the right, with the Rawhide Kid in the background. He then zooms in a little so that we only see the drawn gun of the left figure and the bartender’s frightened face, with the Kid’s expression changing to shock. In panel three, the gunfighter is now on the right and the Kid moves into the left position previously occupied by the bartender. If we even notice the reversal, this might break the flow, but we are still capable of making the transition. The Kid then stays in that position, while the camera gradually pulls back to where we see the full figures in an action sequence. The reader’s eye smoothly and easily makes the connections in between the panels, and the sequence is ingeniously fluid and dynamic.

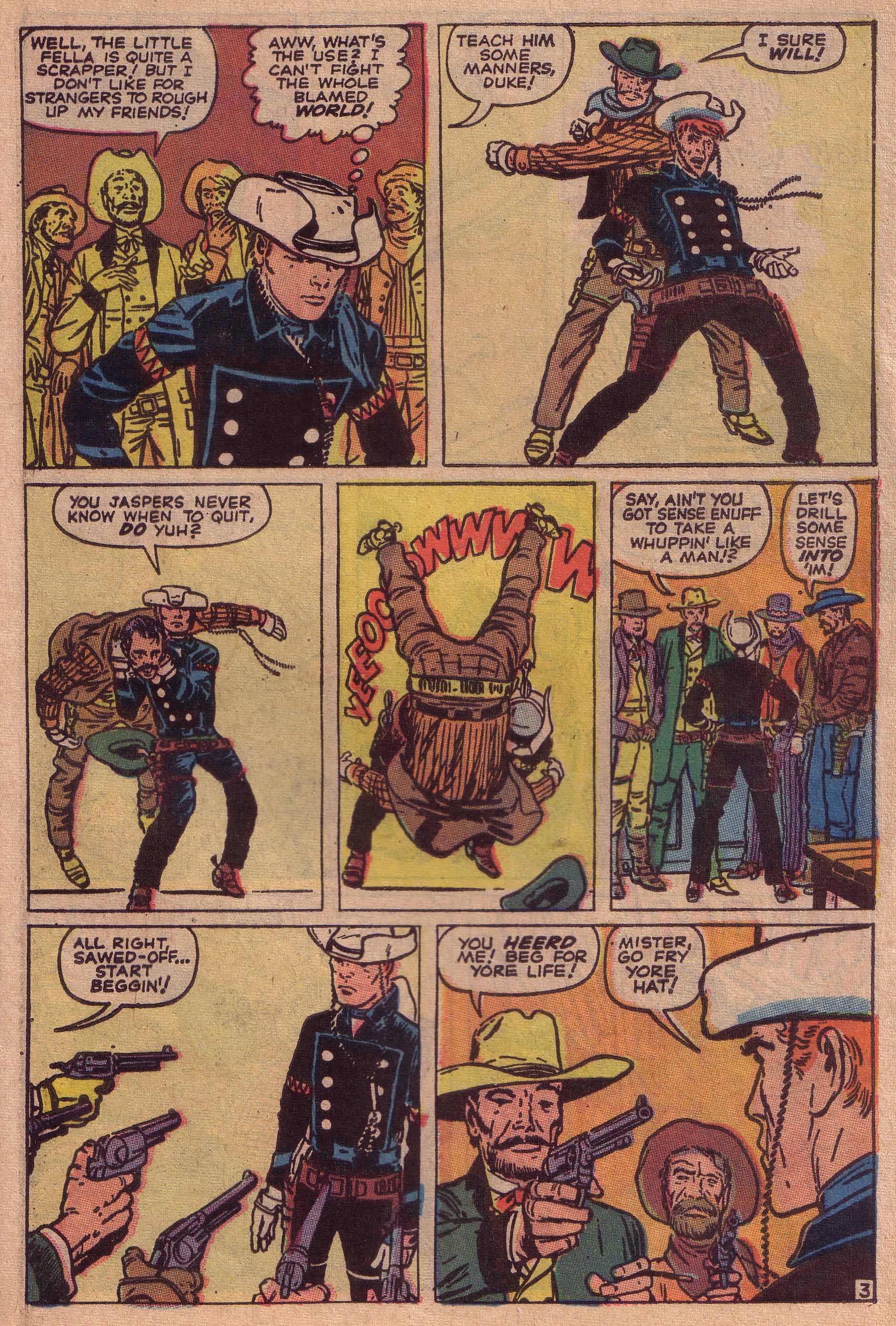

On the following page above, the sequence in the bar continues apace. There is nothing particularly unique about this story except the telling makes it so. The thing about most of these Rawhide Kid stories is that is all about the pacing, and that is all Kirby’s doing. As the page begins, we see a medium shot of the Kid with figures behind him. His assailant approaches to swing at him, and the camera basically pulls back on the full figure shot of the action, as on the previous page. The continuity in panel two through four is deceptively simple and ingenious as the Kid deftly reaches back and throws his attacker over his shoulders. Kirby particularly enjoys using the full figure of the victim partially obscuring that of the victor, just showing enough of the kid to suggest his action. The triangulation of six guns pointed at the Kid in panel six is also ingenious and deceptively simple.

Again, let me emphasize how much the drama of this story is a result of the way it is broken down into continuity. The plot could simply be described as “Man walks into a bar to order a glass of milk and bunch of gunmen pick a fight with him. He wins.” The story is pantomime. It could almost be as effective devoid of dialog.

As the 1960’s progressed, Kirby used this sort of full sequence continuity less and less. Captain America was one series wherein he enjoyed using what he referred to as “choreography” in depicting fight scenes. This page from Tales of Suspense #81 is an especially dynamic one in which you can see the contrast between The King’s earlier style of using between six and nine panels per page and his later tendency to use three to four larger panels in continuity. This often allows for broader movements and more explosive action.

In the first panel, Cap swings his shield, and the arc motion is picked up by the creature’s blow in panel two. Cap falls back and his extended arm gestures to the third panel below as the creature smashes down with a boulder. In the final panel, Cap thrusts upward, counterattacking.

The earlier Rawhide Kid pages strike me as being slower paced, with a bit of humor and nuance. Kirby is playing with the conventions of the Western, and there is almost a slapstick element present here. In contrast, the Captain America sequence is dead serious and devastatingly powerful.

It is fascinating to see the changes in Kirby’s storytelling methods, as we contrast these two stories, separated by several years. It makes me wonder in particular, what caused Kirby to change his approach in storytelling. Was it something as simple as the nature of the stories being told, or was it something changing in the nature of the world and the artist’s perception of it. These are questions too profound for a column of this nature to tackle.

Image 1-2-Rawhide Kid#28 Jack Kirby, Dick Ayers, Stan Lee

Image 3- Jack Kirby, Frank Giacoia, Stan Lee