Recently, John Butler, one of the posters on the Kirby Museum list sent me some scans from his personal collection of original art. Jack Kirby drew these pages during what is generally referred to as the Atlas pre-hero Monster period between 1959 and 61. A year or so before Kirby and Lee released the Fantastic Four, the two creators were producing stories featuring various supernatural creatures, more or less in step with a market that favored such monstrosities.

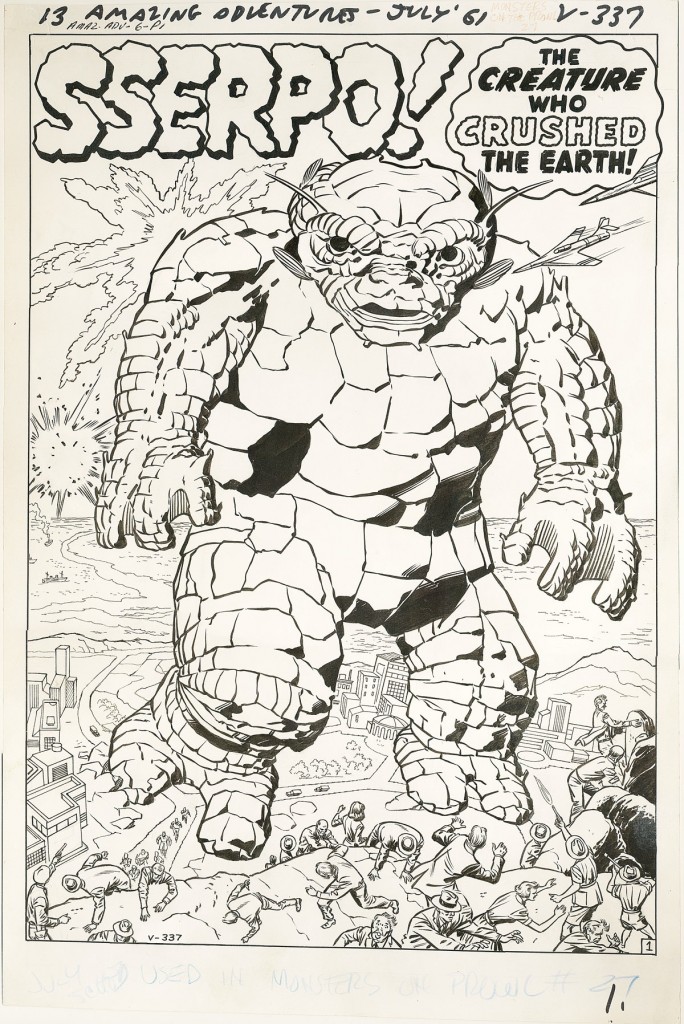

One of John’s pages starred a scaly monster called Sserpo who appeared in Amazing Adventures #6. Because of its skin texture, Sserpo somewhat resembled the Thing, and therefore, some may consider him a visual prototype for that hero. Seeing Sserpo reminded me of how popular saurian creatures were back when Kirby was doing these sorts of stories. Like most boys of that period, I always had a fondness for such beasties, and Kirby certainly had a magical way with them.

Kirby also excelled at drawing dragon-like creatures, Fin Fang Foom, introduced in Strange Tales #89 was certainly the best well known of such dragons. What many fans don’t realize is that a similar beast known as Grogg was featured previously in Strange Tales #83. Grogg and Fin Fang Foom appear to come from similar stock, and in the earlier story, Grogg is shown as one of a species of such mythical reptiles that invaded China centuries ago.

For me, Strange Tales #83 is one of Kirby’s most powerful and effective monster covers. The viewer’s eye moves from the creature’s raised right arm, down across its face and to his left hand thrusting to the right to seize the jet. The motion of the dragon’s tail swoops up towards the left arm and back to the focal point of the creature’s face, which the jets on the left and right also point to. Grogg’s left claw is huge in forced perspective, reaching out to grab and pull us into the book.

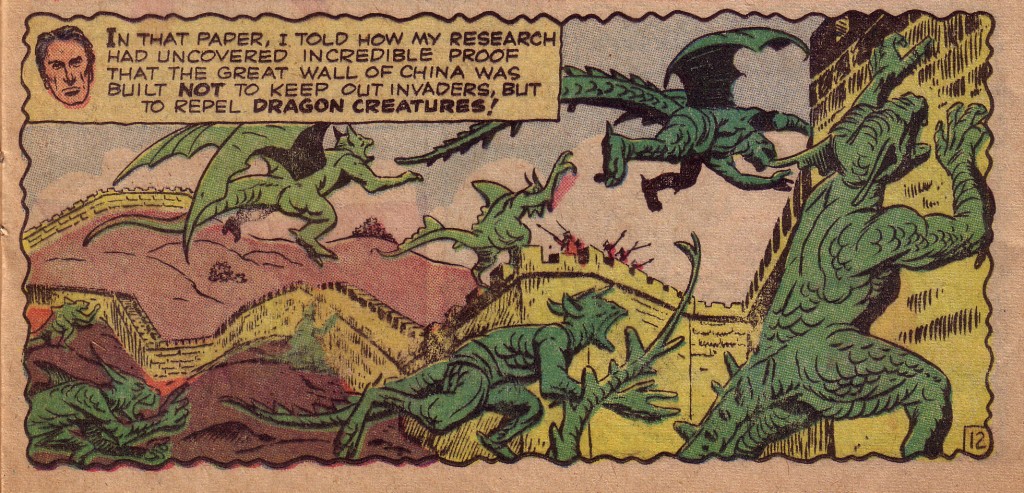

Towards the end of the story there is a two-panel sequence that is an example of Kirby at his most inventive. In a way, it is a shame that the panels are not seen on the same page. In fact, the pages are not even placed next to one another in the printed comic. The first panel is at the bottom of page twelve, so there is a strong notion that Kirby designed it knowing what was to follow at the top of the next page. In the first panel, the dragons are swarming towards the great wall, and the undulating shape of the turreted structure emphasizes their motion. The dragon farthest to the right is climbing upward, bringing the eye to the next panel, which is at the top of the following page.

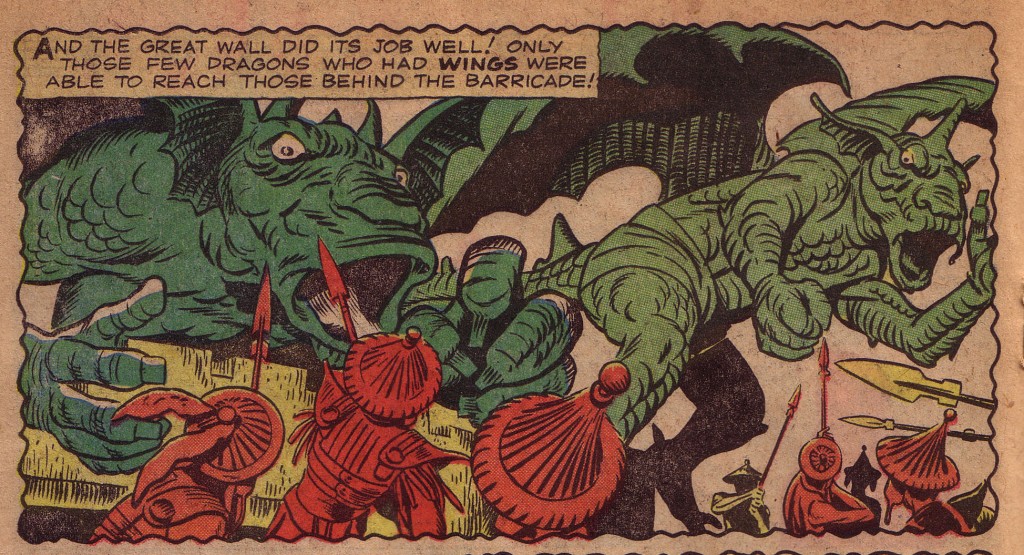

In the following panel, the dragons surge over the wall. Kirby has the dragon on the left looming; mouth agape in a most frightful manner, while the one on the right has cleared the wall, again underlining the power of their rightward trajectory.

When Kirby and Lee made the move from monsters to superheroes by introducing The Fantastic Four, the team covered their bases by not only having monsters as adversaries in the first several issues, but also featuring the monstrous Thing and the brutish Hulk as heroes. Kirby would continue the use of dragons and other saurian creatures in his stories throughout his career. In the seventies, he brought us Devil Dinosaur, a creation that met with mixed reaction. Regardless of one’s opinion of that series, I doubt if anyone would disagree that this two-page spread from issue #4 is a stunning piece of artwork.

The power and dynamism of this page is obvious. It is a vivid hallucinogenic tableau that explodes in the subconscious like a primordial archetype of ancestral terror. Although largely representational, the drawing is also abstract in its use of shape and design, which is true of much of Kirby’s work. With its liberal use of the eye motif, the picture is surreal more than realistic. The eyes are looking out at us, but they also serve as windows into the inner mindscape.

This page has been singled out for another reason. During an interview with Glen David Gold, comic’s creator, Will Eisner made a somewhat dismissive comment about Kirby. The words are Gold’s.

“Eisner mentioned he was uncomfortable calling Kirby someone with heavy artistic intent. I paraphrase, but Eisner felt Jack was mostly

concerned with hitting his page count, telling good stories, and

keeping his family fed. Not pursuing some aesthetic ideal — to seek

that motive in Kirby’s work was, he suggested, misguided. I happened to be holding the original artwork to the Devil Dinosaur #4 double-splash, which I turned around and showed Eisner — who took a moment, and said something uncharacteristic: “Okay, I might be wrong.”

— Glen David Gold, _Masters of American Comics_, 2005, reprinted in TJKC 50

It is interesting to me that someone like Eisner would have such an opinion about Kirby, but equally interesting is that this one powerful image could change his mind so quickly. There are many notions about what the nature of true art is. Critics and historians with elitist agendas concoct most of these notions. Authorities such as those might be unlikely to call Kirby’s work “fine art.” As an artist myself, I would not hesitate to do so.

Visual 1- Amazing Adventures #6 Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, George Klein

Visual 2- Strange Tales #83, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Dick Ayers

Visual 3-4 Ibid

Visual 5-Devil Dinosaur #4 Jack Kirby, Mike Royer

Quote from Gold, Glen David. “Lo, From the Demon Shall Come – the Public

Dreamer!!!” Masters of American Comics. 2005. Page 261.