In the introduction to the first Marvel Masterworks edition of the Rawhide Kid, Stan Lee suggested that the Kid was a superhero prototype. When the series debuted about a year before the first issue of the Fantastic Four, it seemed that Kirby and Lee were indeed getting in the zone. Compared to the run of the mill Western heroes, the smoldering young Kid certainly felt like a superhero in his skin tight, ink black outfit. He was supernaturally fast on the draw and a real scrapper in a fight. Next to Kirby’s steely eyed six footers, the Rawhide Kid was a bantamweight, a wiry little black leopard.

As he did with the good Captain, Kirby put the Kid through his paces, pitting him in brawls against multiple foes twice his size. Throughout his career, Kirby’s fight scenes had always taken advantage of the sequential continuity of panels on a comic book page, using a certain degree of follow through motion from one frame to the next. The lithe black silhouette of the Rawhide Kid inspired Kirby to really explore the limits of kinetic continuity. The positioning of the Kid’s negative shape was like an anchor for the eye, a naturally spotted black to give contrast and motion.

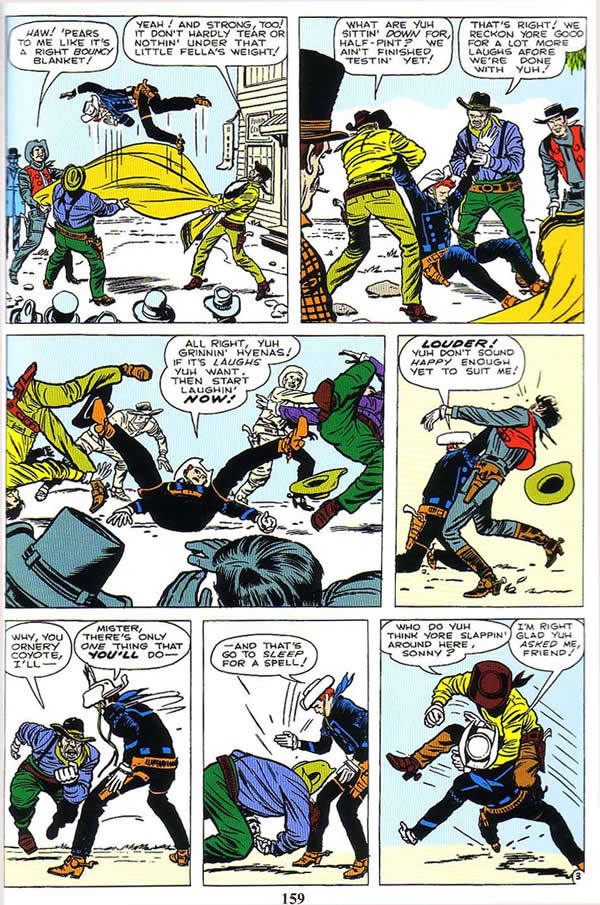

Black spotting is by some considered to be a mysterious art trick and is often not well understood. In reality it is a reasonably simple concept. It is essentially about the contrast between light and dark. A black shape or dark shadow placed behind or next to another object will push that object fore ward or better define it. In this case, it is the Kid’s black costume that makes him the focus of attention when he is strategically positioned in relation to other figures. This page from Rawhide Kid #32 is one of the best composed of the series run.

Kirby’s figures are nearly always arranged in a pivotal relationship to one another, and in this case, the eye effortlessly follows the Kid’s reoccurring form across the page. As the eye enters the first panel, it sees the word balloon on the left and then the black shape of the Kid in the air. The curvature of the blanket brings the eye in a circle to take in the entire panel, and the Kid’s legs and the man in the yellow shirt move the eye rightward to panel two. The black stovepipe hat brings the eye to the second appearance of the man in the yellow shirt and the spotted black of the Kid being held by him. The sweep of the blanket in the lower right corner leads the eye to panel three and the man in the green pants, whose bent right leg points directly to the dynamic kicking figure of the Kid. Various elements throughout the seven panels make this particular figure the focal point of the entire page.

The man with the green trousers serves to both bring the eye to this third panel and to take it out. As he is literally being kicked out of the panel, his left leg moves us to panel four, with the kid rising and striking the man with the red vest. This figure’s left foot points us to the first of the final three panels, which are beautiful examples of sequential action, and perfectly balanced medium shots of the Kid fending off attack and being attacked yet again.

The Kid is almost always on the defensive. An outlaw and a loner, he is on the run constantly. He never looks for trouble but trouble always finds him. In an article in the Jack Kirby Collector #16, by Jerry Boyd, “The King and the Kid”, Boyd notes the similarity in a resting pose the Kid is taking in this splash panel to the reclining figure from a still of James Dean in the film, “Giant.”

The panel is from Rawhide Kid #31, Shootout with Rock Rorick. The Kid’s figure is beautifully framed by objects in a virtual panel within a panel. The comparison to the James Dean pose is fairly obvious, but what follows in the conclusion of the same story is even more telling.

Both Lee and Kirby have said that to some degree they based their version of the Rawhide Kid on another young rebel actor, Steve McQueen. It is just my good fortune to have stumbled on compelling evidence of this, when I purchased a tape of the 1959 TV series, “Wanted, Dead or Alive,” starring McQueen. On that tape was an episode entitled, “The Kovack Affair.” At the end of the show, McQueen’s bounty hunter hero, Josh Randall breaks into the office of a crooked gambling boss named Kovak and beats him savagely in order to compel Kovak to surrender his ill gotten casino holdings. This TV segment is nearly lifted intact by Kirby in the last page of the Rorick story, wherein the Rawhide Kid, in another virtuoso display of sequential action repeatedly pummels the cowardly rancher Rock Rorick into submission. The physical resemblance between TV’s Kovak and Kirby’s Rorick is unmistakable. Both men are burly mustached men with suits and string ties. Both beatings are one sided, in that the villain is overwhelmed by the savagery of his attacker and is incapable of resistance.

Both Randall and the Kid announce that they enjoyed administering their beatings so much that they wish that their respective villains had held out a bit longer. The final six panels of these sequences are some of Kirby’s best, and notable for the reason that the villain takes one devastating hit after another and is totally incapable of defending himself.

When Kirby abandoned the Rawhide Kid to focus exclusively on superheroes, he seldom returned to this sort of high panel count cinematic sequential storytelling style until his reintroduction of Captain America with his acrobatic prowess.

When Marvel decided to reduce the size of the boards its artists worked on, Kirby began to rely on larger panels and his work generally became more monumental, the panel count less numerous and the action on the page less continuous.

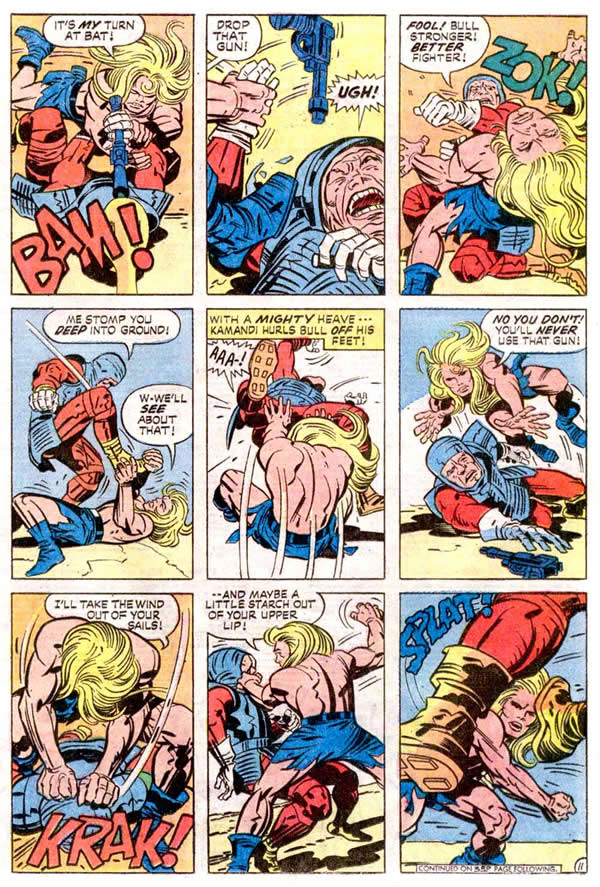

Strange then, that in issue#14 of Kamandi, Kirby appears to pay homage to this very Rawhide Kid page. If one looks at the final six panels of this fight scene with bison rider, Bull Bantam, one sees in the fourth panel something very similar to the composition of panel three on the Rawhide Kid page. Both pages have the figures on the left raising one leg to kick downward. The following panel on both pages shows the back of one figure partially blocking the other. The final two panels of both sequences both show the heroes, Kamandi and the Kid grabbing their opponents by their upper torsos and knocking them away with a final blow.

Did Kirby consciously return to that Rawhide Kid page, or is this merely a bizarre coincidence. First off as I have noted, Kirby did very few pages in his later work with so high a panel count, nine in all. In his Fourth World stories, the panel count seldom goes above six. Secondly, he seldom extended a fight sequence to such lengths in his later work and certainly not in this condensed form. Was it the pseudo Western theme of the rodeo in the Kamandi story that inspired him to return to an earlier work for inspiration?

At any rate, it is wonderful to have the opportunity to compare the stylistic differences in two pieces of work separated by more than ten years. As I have said, it was just a stroke of luck to stumble on these examples of Kirby swiping from Kirby. It is always a pleasure to have a fresh revelation relating to the King’s work, particularly when you have a window into his thought processes and inspirations.

Citations

1 – Kirby, Jack (art), Lee, Stan (story) Ayers, Dick (inks) “Beware of the Barker Brothers,” Rawhide Kid #32 pg#3. from Marvel Masterworks Rawhide Kid volume 2 pg.#159

2 – Kirby, Jack, (art) Lee, Stan (story) “Shootout With Rock Rorick,” Rawhide Kid #31 pg. #1, from Mighty Marvel Western #6

3 – Ibid, pg#6

4 – Kirby, Jack (art, story), Royer, Mike (inks) “Winner Take All,” Kamandi #14

Mr. Burroughs’ comparison between the works of Kirby is very fascinating. He has introduced me to some of the best comics. I particularly like the way he describes the kinetics and eye movement of the Rawhide kid panel. His attention to the detail is amazing. I would love to read more. Keep blogging.