A great deal has been written about Stan Lee’s work as a writer with Jack Kirby. Many are of the opinion that Kirby did his best work with Lee and that the artist’s solo work suffers in comparison to their collaboration. As popular as this notion is, it is still merely an opinion. What is certain is that whether alone or in collaboration, Kirby’s vision is unique and his ability to translate the ideas of a story is second to none.

At some point in the sixties, Lee acknowledged that he began working with Kirby and several of the other Marvel artists, utilizing a technique he refers to as the Marvel Method. This entailed having a brief story conference with the artist, whereupon the latter would plot and draw the story, to be later dialogued by Lee. It is difficult to know when this style of writing began, but we have a pretty good idea that an artist such as Kirby, who had been involved in creating his own stories and characters for his entire life would probably have been making significant plot contributions from the beginning of his association with Lee.

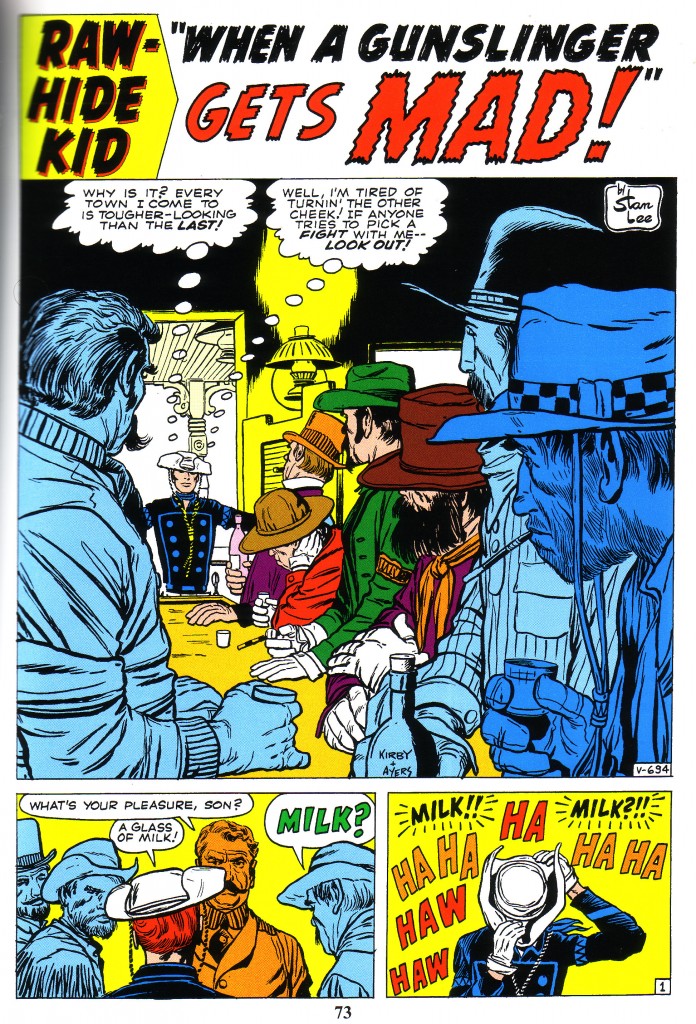

Kirby was consistently capable of taking a fairly pedestrian concept and injecting it with drama, simply by his visual choices and sequencing style. This is always clear when one considers his dynamic way with action. Often, the artist would begin his story with a bit of explosive action, such as a splash panel of the Rawhide Kid leaping from his horse onto a moving stagecoach. However, Kirby could just as often begin his story less explosively, with a shot of a character entering a saloon, as in this panel from Rawhide Kid #28.

The sequence is deceptively simple, but in fact it is masterfully composed; the eye enters the panel with the bartender’s figure on the left, and travels down to his moustache, which points to the Kid. However, you will also notice the eye may choose to continue to move down the bartender’s arm to the crook of his elbow and to his hand. The eye continues rightward and up the blue shaded drinker and then leftward across the row of heads to the small figure of the Kid. Very few artists possess the skill and the intelligence to pull off a composition of this sort. Kirby has created an entire environment of hostility here, foreshadowing the conflict to come. The small blurb in the upper right hand corner informs us that this story is by Stan Lee, but in this case it is not the writer who has set the tone. It is the artist who has set the stage. It is a very simple story, after all. A man walks into a bar, orders a glass of milk and gets into a fight over it. In the end, it is the interpretation that makes the story a dramatic tour de force.

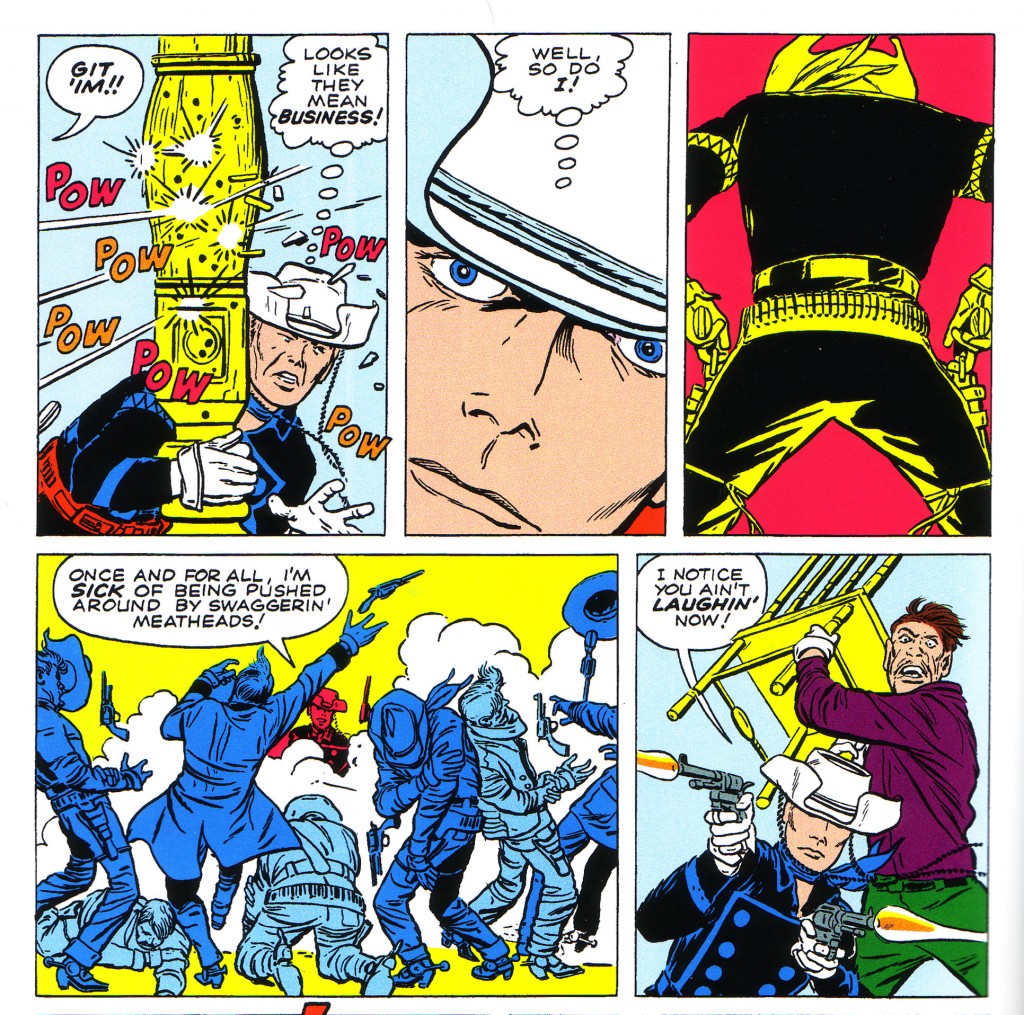

This idea cannot be over stressed. Unless a writer is providing an artist with complete scripts, with specific instructions for camera angles and continuity, the artist is given the dramatic choice of pacing the story, and in Kirby’s case, one can be fairly certain that the artist is in charge of such decisions. Take as another example this sequence later in the same story, where that Kid is ducking a hail of gunfire.

As he retreats behind a post, we can see his expression, squinting involuntarily to avoid the flying wood chips. Then the camera zooms in for a transitional close up as the Kid regains his resolve. The POV changes dramatically in the third panel to the Kid’s back as he draws his guns. In the fourth panel he has disarmed a half dozen adversaries.

Again, it is the artist’s choices that create the excitement of this sequence. Even if the script reads, “Kid ducks, draws his guns and fires”, this still leaves the artist a nearly infinite array of interpretative choices.

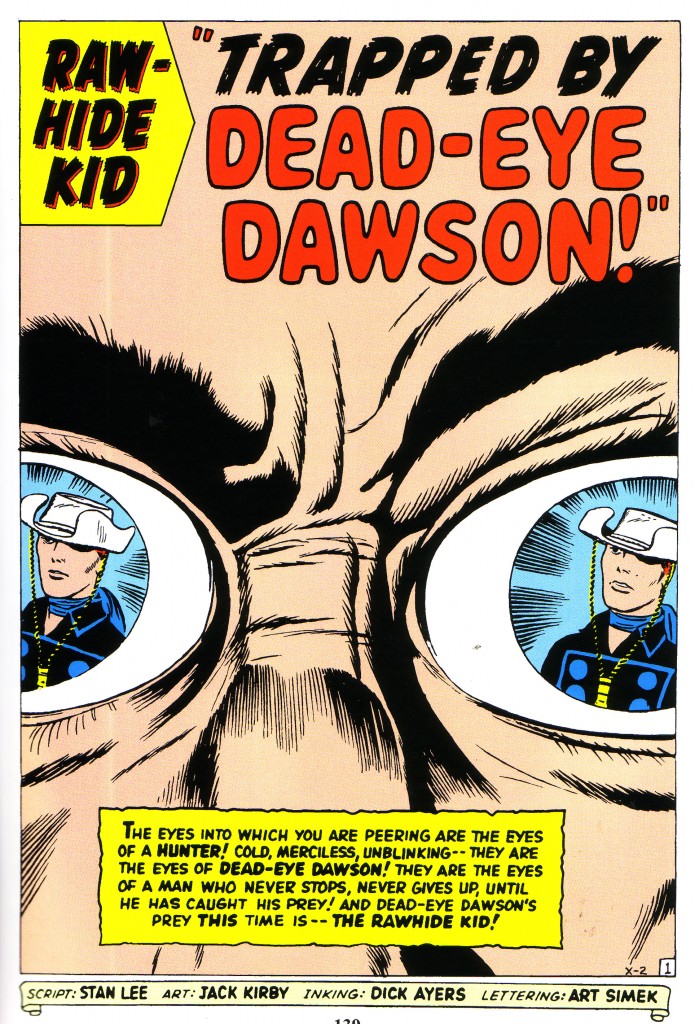

Kirby is nearly always innovative in the way he begins a story. Observe in this case the dramatic use of huge eyes that dominate the page, containing the images of the hunted Rawhide Kid.

Throughout the series, the Rawhide Kid is depicted as a hunted man. In nearly every episode, he is shown attempting to evade the law or avoid a fight or an encounter that might draw unwanted attention to him. He is nearly always unsuccessful. Again and again he is forced to reveal his amazing prowess with a gun and then he must flee again to escape capture.

Obviously, this concept can get old fairly quickly, and yet Kirby was consistently capable of crafting inventive ways to emphasize the Kid’s dilemma.

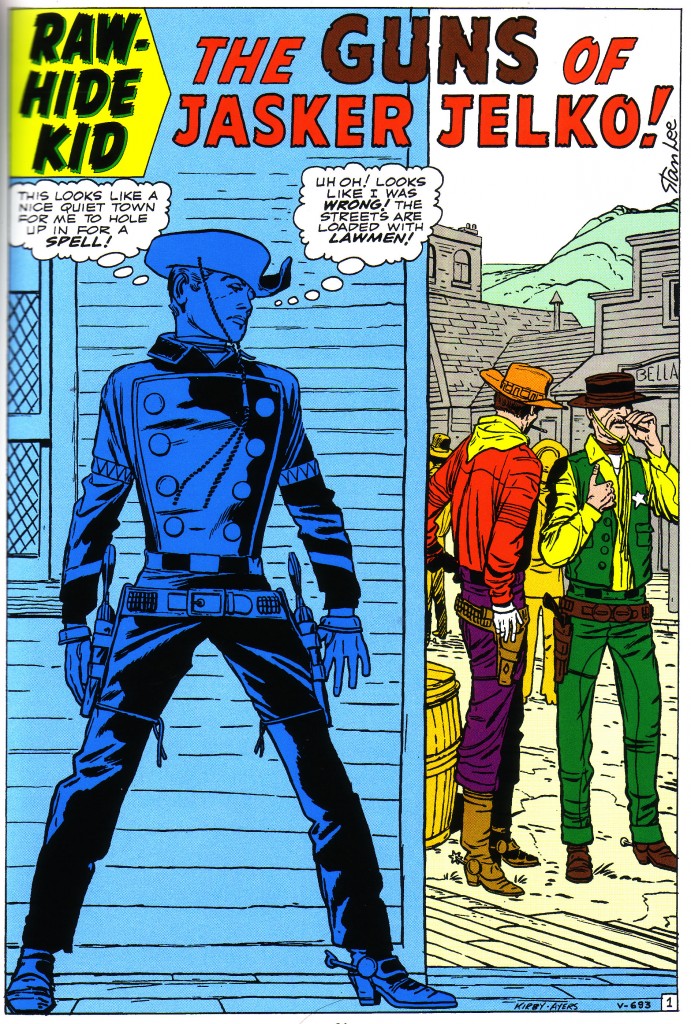

For example if we look at another page from Rawhide Kid #28, we see the Kid hiding in the shadows, trying to escape detection in a town full of lawmen. The splash panel shows him flattened against the side of a building, while around the corner, several lawmen are standing. Here, Kirby has created one of his panel within a panel compositions, with the Kid isolated in his own space, the secure shadow world of the fugitive. As soon as he steps out of the shadows, he becomes a victim of the world of predation.

Again, this appears to be a relatively simple visual story telling device to convey the emotion of isolation combined with the fear of being apprehended, and yet if you alter the composition in the slightest, it is rendered less effective. If for example, we make the space that the Kid occupies smaller, we diminish his psychic as well as physical importance in the picture. The lawmen occupy a space roughly approximating that of a doorway. If the kid steps through, he abandons his sanctuary and enters their world.

We instantly believe the worlds that Kirby has constructed, without question. It all seems to logical and matter of fact.

It is only when we take the time to analyze his work that we realize how much mastery and intelligence is involved in what appear to be simple, straight fore ward artistic decisions.